OECD/IMHE Project Supporting the Contribution of Higher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pädagogische Hochschule Viktor Frankl Hochschule Austria The

Pädagogische Hochschule Viktor Frankl Hochschule Austria The Private University College of Education of the Diocese of Linz Austria Vienna University of Teacher Education Austria Belarus State Pedagogical University 'M. Tank' Belarus Catholic College, Louvain Belgium Haute École de Namur-Liège-Luxembourg Belgium Charles University, Prague Czech Republic 'J.E. Purkynì' University in òstí nad Labem Czech Republic Palacky University, Olomouc Czech Republic Technical University of Ostrava Czech Republic University of Hradec Králové Czech Republic Bornholms Sundheds- og Sygeplejeskole Denmark Copenhagen Business School Denmark Metropolitan University College Denmark Professionshøjskolen UCC Denmark Roskilde University Denmark University College Absalon Denmark University College Lillebælt Denmark University College South Denmark Denmark VIA University College Denmark Sjúkrarøktarfrødiskúli Føroya Faroe Islands Humak University of Applied Sciences Finland Kemi-Tornio Polytechnic Finland Laurea University of Applied Sciences Finland Saimaa University of Applied Sciences Finland Turku University of Applied Sciences Finland University of Eastern Finland Finland University of Lapland Finland University of Tampere Finland Vaasa Polytechnic Finland Yrkeshögskolan Novia Finland KEDGE Business School France Normandy Business School France University François Rabelais of Tours France University Jean Monnet Saint-Etienne France University of Burgundy, Dijon France University of Caen France University Paris Descartes (Paris V) France Albert Ludwig University -

Innovative Networking for Optics and Photonics Active Learning

INNOVATIVE NETWORKING FOR OPTICS AND PHOTONICS ACTIVE LEARNING P. García-Martínez1, I. Fernández1, I. Moreno2, M. M. Sánchez-López3 , D. Mas4, J. Espinosa4, C. Ferreira-Gauchía5, A. Esteban-Martín1, E. Roldán1 and F. Silva1 1 Department d’Òptica i d’Optometria i Ciències de la Visió, Universitat de València, 46100 Burjassot, SPAIN 2 Departamento de Ciencia de Materiales, Óptica y Tecnología Electrónica, Universidad Miguel Hernández, 03202 Elche, SPAIN 3 Instituto de Bioingeniería, Universidad Miguel Hernández, 03202 Elche, SPAIN 4Departament d’Òptica, Farmacologia i Anatomia. Universitat d’Alacant. 03690 Alicante, SPAIN 5Departamento de Matemáticas, C. Naturales y C. Sociales aplicados a la Educación. Universidad Católica de Valencia, 46001, València, SPAIN ABSTRACT Networking means to interconnect people sharing an interest in the success of a particular enterprise. We present our Innovative Education Networking which develop learning tools for Optics and Photonics. The network is (a) (b) composed by University of Alicante, the University of Miguel Hernández in OBJECT Elche, Valencia Catholic University and the University of Valencia. The academic networking staff is expert in Optics and Photonics teaching. Other IMAGE student demands multimedia applications, in that sense we are developing Figure 2: Different snapshots of Geometrical Optics Lab video-tutorials several online materials based on video-tutorials of laboratory experiences, also different activities of outreach to enhance students creativity and Video-tutorials have a duration of ten minutes approximately. At the beginning of interest in Optics and Photonic. That will result in interesting educational the video-tutorial we review the theory and we clarify the objective of the synergies between universities and promote student autonomy for learning practice. -

Reviewers for Academy of Finland's September 2019 Call the Research

1 (16) Reviewers for Academy of Finland’s September 2019 call • Academy Project funding • Academy Professor (letters of intent) • Academy Research Fellow • Postdoctoral Researcher • Clinical Researcher • Funding for sport science research projects from Ministry of Education, Science and Culture Data retrieved from the Academy’s information systems. A total of 732 reviewers from 38 different countries participated in the review of applications submitted in the September 2019 call. The reviewers are listed by Academy research council. The Research Council for Biosciences, Health and the Environment enlisted a total of 194 reviewers from 20 different countries. • Senior Researcher, Maurizio Bettiga, Chalmers University of Technology • Professor, Wender Bredie, University of Copenhagen • Emeritus Professor, Michael Morgan, University of Leeds • Associate Professor, Laurent Poirel, University of Fribourg • Professor, Peter Punt, Leiden University & Dutch DNA • Professor, Ulrika Rova, Luleå University of Technology • Principal Scientist, Hugo Streekstra, DSM Biotechnology Center • Professor, Martin Attrill, University of Plymouth • Professor, Elena Conti, Univerisity of Zurich • Professor, André de Roos, University of Amsterdam • Docent, Marleen De Troch, Ghent University • Associate Professor, Brian Fredensborg, University of Copenhagen • Professor, Jean-Michel Gaillard, CNRS - University of Lyon • Emeritus Professor, Colin Hansen, University of Adelaide • Professor, Joachim Kurtz, University of Muenster • Dr., Thomas Mehner, Leibniz-Institute -

Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision

EUROPE Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision Cecile Hoareau McGrath, Joanna Hofman, Lubica Bajziková, Emma Harte, Anna Lasakova, Paulina Pankowska, S. Sasso, Julie Belanger, S. Florea, J. Krivogra Prepared for The European Commission Project number 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision (GAIHE) Project information Project acronym: GAIHE Project title: Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision Project number: 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF Sub-programme or KA: Lifelong Learning Programme Project website: http://www.he-governance-of- innovation.esen.education.fr/ Reporting period: From 01/10/2013 To 31/06/2016 Report version: 1 Date of preparation: 2015–2016 Beneficiary organisation: Maastricht University, School of Governance École Normale Supérieure de Lyon Dublin Institute of Technology University of Latvia Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu Comenius University in Bratislava University of Ss. Cyrill and Methodius, Trnava University of Maribor University of Salamanca, ECYT Institute University of Alicante 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF 2 / 217 Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision (GAIHE) University of Strasbourg RAND Europe Project coordinators: Dr Cecile McGrath & Joanna Hofman Project coordinator organisation: RAND Europe Project coordinator telephone number: + 44 1223 273 850 Project coordinator email address: [email protected] [email protected] 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF 3 / 217 Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision (GAIHE) This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. -

Humanistic Futures of Learning

Humanistic futures of learning Perspectives from UNESCO Chairs and UNITWIN Networks UNESCO Education Sector Education is UNESCO’s top priority because it is a basic human right and the foundation on which to build peace and drive sustainable development. UNESCO is the United Nations’ specialized agency for education and the Education Sector provides global and regional leadership in education, strengthens national education systems and respondsto contemporary global challenges through education with a special focus on gender equality and Africa. Published in 2020 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2020 ISBN 978-92-3-100369-1 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The present license applies exclusively to the text content of the publication. For use of any other material (i.e. images, illustrations, charts) not clearly identified as belonging to UNESCO or as being in the public domain, prior permission shall be requested from UNESCO. ([email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Programme Transius Conference 2018

2018 PROGRAMME TRANSIUS CONFERENCE 2018 Centre for Legal and Institutional Translation Studies Faculty of Translation and Interpreting University of Geneva, 18-20 June 2018. ORGANISING COMMITTEE Diego Guzmán Bourdelle-Cazals, Fernando Prieto Ramos (chair) and Annarita Felici. SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Anabel Borja Albi (Jaume I University), Łucja Biel (University of Warsaw), Samantha Cayron (University of Geneva), Valérie Dullion (University of Geneva), Jan Engberg (University of Aarhus), Mathilde Fontanet (University of Geneva), Jean-Claude Gémar (University of Montreal and University of Geneva), Sonia Halimi (University of Geneva), Anne Lafeber (United Nations), Karen Mcauliffe (University of Birmingham), Mariana Orozco Jutorán (Autonomous University of Barcelona), Colin Robertson (Council of the European Union), Peter Sandrini (University of Innsbruck), Susan Šarčević (University of Rijeka), Catherine Way (University of Granada). The Organising Committee would like to thank the volunteer staff for their valuable assistance, as well as the following bodies for their support: • Administrative Committee of the University of Geneva • Continuing Education Service of the University of Geneva • Faculty of Translation and Interpreting of the University of Geneva With the kind support of: TRANSIUS CONFERENCE 2018 | PROGRAMME 9.15-9.30 Opening | R080 9.30-10.30 KEY 1 | R080 18 JUNE 2018 10.30-11.00 POST 1A | Coffee break - Poster session 11.00-12.20 PAR 1.1 - ME1 | R080 PAR 1.2 - TE1 | R060 PAR 1.3 - TT1 |R070 12.20-14.00 Lunch break 14.00-15.20 PAR -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Contributions of Service-Learning on PETE Students' Effective Personality

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Contributions of Service-Learning on PETE Students’ Effective Personality: A Mixed Methods Research Oscar Chiva-Bartoll 1 , Antonio Baena-Extremera 2 , David Hortiguela-Alcalá 3 and Pedro Jesús Ruiz-Montero 4,* 1 Department of Education and Specific Didactics, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Universitat Jaume I, 12071 Castellón, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Education Sciences, Faculty of Education, University Campus of Cartuja, University of Granada, s/n, 18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Specific Didactics, Faculty of Education, University of Burgos, 09001 Burgos, Spain; [email protected] 4 Department of Physical Education and Sport, Faculty of Education and Sport Sciences, Campus of Melilla, University of Granada, 52071 Melilla, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 23 November 2020; Published: 25 November 2020 Abstract: Service-learning (SL) is a pedagogical model focused on achieving curricular goals while providing a community service. Previous research suggests that SL might promote qualities such as self-esteem, motivation, problem-focused coping, decision-making, empathy, and communication, which are associated with a psychological construct known as students’ Effective Personality (EP). These studies, however, did not specifically analyse the direct effects of SL on this construct. The aim of this study is to explicitly analyse the effect of SL on Physical Education Teacher Education (PETE) students’ EP using a mixed methods approach. The quantitative part of the approach followed a quasi-experimental design using the validated “Effective Personality Questionnaire for University Students”, which includes four dimensions: “Academic self-efficacy”, “Social self-realisation”, “Self-esteem”, and “Resolutive self-efficacy”. -

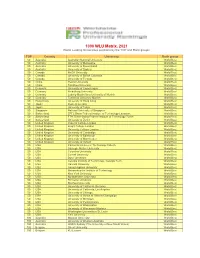

WLU Table 2021

1000 WLU Matrix. 2021 World Leading Universities positions by the TOP and Rank groups TOP Country University Rank group 50 Australia Australian National University World Best 50 Australia University of Melbourne World Best 50 Australia University of Queensland World Best 50 Australia University of Sydney World Best 50 Canada McGill University World Best 50 Canada University of British Columbia World Best 50 Canada University of Toronto World Best 50 China Peking University World Best 50 China Tsinghua University World Best 50 Denmark University of Copenhagen World Best 50 Germany Heidelberg University World Best 50 Germany Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich World Best 50 Germany Technical University Munich World Best 50 Hong Kong University of Hong Kong World Best 50 Japan Kyoto University World Best 50 Japan University of Tokyo World Best 50 Singapore National University of Singapore World Best 50 Switzerland EPFL Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne World Best 50 Switzerland ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich World Best 50 Switzerland University of Zurich World Best 50 United Kingdom Imperial College London World Best 50 United Kingdom King's College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Cambridge World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Edinburgh World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Manchester World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Oxford World Best 50 USA California Institute of Technology Caltech World Best 50 USA Carnegie -

Communication on Sustainability in Spanish Universities: Analysis of Websites, Scientific Papers and Impact in Social Media

sustainability Article Communication on Sustainability in Spanish Universities: Analysis of Websites, Scientific Papers and Impact in Social Media Daniela De Filippo 1,2,* , Javier Benayas 1,3 , Karem Peña 4 and Flor Sánchez 1,4 1 Research Institute for Higher Education and Science (INAECU), 28903 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (J.B.); fl[email protected] (F.S.) 2 Department of Library Science and Documentation, University Carlos III, 28903 Madrid, Spain 3 Department of Ecology, Autonomous University of Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain 4 Department of Social Psychology, Autonomous University of Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: dfi[email protected] Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 6 October 2020; Published: 8 October 2020 Abstract: This study analyses how Spanish universities are communicating their commitment to sustainability to society. That entailed analysing the content of their websites and their scientific papers in sustainability science and technologies and measuring the impact of such research in social media. Results obtained from bibliometric approaches and institutional document analysis attest to intensified interest in sustainability among Spanish universities in recent years. The findings revealed an increase in the number of universities using terms associated with sustainability to designate the governing bodies. The present study also uses an activity index to identify universities that devote high effort to research on sustainability and seven Spanish universities were identified with output greater than 3% of the total. Mentions in social media were observed to have grown significantly in the last 10 years, with 38% of the sustainability papers receiving such attention, compared to 21% in 2010. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

Valencia, Spain

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Directorate for Education Education Management and Infrastructure Division Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Peer Review Report: Valencia, Spain Enrique A. Zepeda, Francisco Marmolejo, Dewayne Matthews, Martí Parellada October 2006 The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the OECD or its Member countries. 1 This Peer Review Report is based on the review visit to Valencia in February/March 2006, the regional Self-Evaluation Report, and other background material. As a result, the report reflects the situation up to that time. The preparation and completion of this report would not have been possible without the support of very many people and organisations. OECD/IMHE and the Peer Review Team for Valencia wish to acknowledge the substantial contribution of the region, particularly through its Coordinator, the authors of the Self-Evaluation Report, and its Regional Steering Group. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE......................................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................6 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS....................................................................................11 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................13