(Inaudible) Set up for Jenny Holzer. Can You Hear Me?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jane Dickson PR Draft3

JAMES FUENTES 55 Delancey Street New York, NY 10002 (212) 577-1201 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JANE DICKSON All That Is Solid Melts Into Air January 16 – February 17, 2019 Reception: Wednesday, January 16, 6-8pm James Fuentes is pleased to present Jane Dickson, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air. The exhibition includes works spanning from the early 1980s to the present, each offering an important document of New York City. Jane Dickson is known for her vivid depictions of Times Square’s nocturnal energy. Born in Chicago, Dickson arrived to New York in 1977, and a year later began a job programming visuals for Times Square’s first digital billboard. She mostly worked the night shift and was responsible for the New Year’s Eve countdown, witness to upturned faces basking in the hallucinatory glow. Two years later she moved to an apartment on 43rd Street and 8th Avenue, where she lived and raised two children with her husband. From this vantage point Dickson observed Times Square after dark, absorbing the seductive haze and structured environment in which figures and shadows moved. Dickson soon began to carry around a small, discrete camera as a way to record fleeting episodes. Many of these impressionistic photographs contain a rich field of dark blackness, punctuated by effervescent neon signs, the glow of a cigarette being lit, the fluorescent insides of a storefront, or the reflection of rain against the streets. As well as her snapshots, Dickson also made rough charcoal sketches describing the posture of figures—rushing, waiting, a young man being frisked, the shape of a cop on a horse—and this very gesture of peering over a ledge, looking in, like the artist. -

Women in the City Micol Hebron Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Art Faculty Articles and Research Art 1-2008 Women in the City Micol Hebron Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles Part of the Art and Design Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hebron, Micol. “Women in the City”.Flash Art, 41, pp 90, January-February, 2008. Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women in the City Comments This article was originally published in Flash Art International, volume 41, in January-February 2008. Copyright Flash Art International This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles/45 group shows Women in the City S t\:'-: F RA:'-.CISCO in over 50 locations in the Los ments on um screens throughout Museum (which the Guerrilla Angeles region. Nobody walks in the city, presenting images of Girls have been quick to critique LA, but "Women in the City" desirable lu xury items and phrases for its disproportionate holdings of encourages the ear-flaneurs of Los that critique the politics of work by male artists). The four Angeles to put down their cell commodity culture. L{)uisc artists in "Women in the City," phones and lattcs and look for the Lawler's A movie will be shown renowned for their ground billboards, posters, LED screens without the pictures (1979) was re breaking exploration of gender and movie marquis that host the screened in it's original location stereotypes, the power of works in this eJ~;hibition. -

Jenny Holzer, Attempting to Evoke Thought in Society

Simple Truths By Elena, Raphaelle, Tamara and Zofia Introduction • A world without art would not only be dull, ideas and thoughts wouldn’t travel through society or provoke certain reactions on current events and public or private opinions. The intersection of arts and political activism are two fields defined by a shared focus of creating engagement that shifts boundaries, changes relationships and creates new paradigms. Many different artists denounce political issues in their artworks and aim to make large audiences more conscious of different political aspects. One particular artist that focuses on political art is Jenny Holzer, attempting to evoke thought in society. • Jenny Holzer is an American artist who focuses on differing perspectives on difficult political topics. Her work is primarily text-based, using mediums such as paper, billboards, and lights to display it in public spaces. • In order to make her art as accessible to the public, she intertwines aesthetic art with text to portray her political opinions from various points of view. The text strongly reinforces her message, while also leaving enough room for the work to be open to interpretation. Truisms, (1977– 79), among her best-known public works, is a series inspired by Holzer’s experience at Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program. These form a series of statements, each one representing one individual’s ideology behind a political issue. When presented all together, the public is able to see multiple perspectives on multiple issues. Holzer’s goal in this was to create a less polarized and more tolerant view of our differing viewpoints, normally something that separates us and confines us to one way of thinking. -

Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey. Lives and works in Los Angeles and New York. EDUCATION 1966 Art and Design, Parsons School of Design, New York 1965 Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021-2023 Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York] [forthcoming] [catalogue forthcoming] 2019 Barbara Kruger: Forever, Amorepacific Museum of Art (APMA), Seoul [catalogue] Barbara Kruger - Kaiserringträgerin der Stadt Goslar, Mönchehaus Museum Goslar, Goslar, Germany 2018 Barbara Kruger: 1978, Mary Boone Gallery, New York 2017 Barbara Kruger: FOREVER, Sprüth Magers, Berlin Barbara Kruger: Gluttony, Museet for Religiøs Kunst, Lemvig, Denmark Barbara Kruger: Public Service Announcements, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2016 Barbara Kruger: Empatía, Metro Bellas Artes, Mexico City In the Tower: Barbara Kruger, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 2015 Barbara Kruger: Early Works, Skarstedt Gallery, London 2014 Barbara Kruger, Modern Art Oxford, England [catalogue] 2013 Barbara Kruger: Believe and Doubt, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria [catalogue] 2012-2014 Barbara Kruger: Belief + Doubt, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC 2012 Barbara Kruger: Questions, Arbeiterkammer Wien, Vienna 2011 Edition 46 - Barbara Kruger, Pinakothek -

Wedel Art Collective Launch Face Masks Designed by Leading Artists

Wedel Art Collective launch face masks designed by leading artists: Jenny Holzer, Rashid Johnson, Barbara Kruger, Raymond Pettibon, Lorna Simpson and Rosemarie Trockel Left to right, face masks designed by: Rosemarie Trockel; Jenny Holzer; Lorna Simpson; Barbara Kruger; Raymond Pettibon and Rashid Johnson. Courtesy Wedel Art Collective. Wedel Art Collective have collaborated with six international leading artists to produce a set of unique artist-designed face masks, all proceeds from which will be donated to international relief efforts and artist support for those affected by COVID-19. Launching exclusively on MATCHESFASHION from 24 August the project draws upon the power of contemporary art to encourage more people to wear face masks to protect, and support. Each of the participating artists are internationally celebrated for their work addressing some of the most important social and political issues of our times. Through the inspiration of these artists’ work, the limited-edition face masks reflect the artists’ passionate and urgent response to the pandemic, highlighting the need for community action. Artists include: Jenny Holzer (b. 1950, Ohio, USA); Rashid Johnson (b. 1977, Chicago, USA); Barbara Kruger (b. 1975, New Jersey, USA); Raymond Pettibon (b. 1957, Arizona, USA); Lorna Simpson (b. 1960, New York, USA); and Rosemarie Trockel (b. 1952, Schwerte, Germany). Jenny Holzer's face mask taps into the necessity of mask-wearing, reading “You – Me”. “I like to think of my work as useful,” Holzer says “That is a recurrent impulse, when something happens in the world, if I have an idea that be properly responsive… Not necessarily a cure or a solution but at least an offering.” Raymond Pettibon's mask design features Vavoom, a figure inspired by Felix the Cat that he has drawn since the mid-1980s. -

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Katarína Belejová Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Bc. Katarína Belejová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr., for his encouragement, patience and inspirational remarks. I would also like to thank my family for their support. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Postmodern Art, Conceptual Art and Social Criticism .............................................. 7 1.1 Social Criticism as a Part of Postmodernity ..................................................................... 7 1.2 Postmodernism, Conceptual Art and Promotion of a Thought .................................. 9 1.2. Importance of Subversion and Parody ........................................................................... 12 1.3 Conceptual Art and Its Audience ...................................................................................... 16 2. American context ..................................................................................................... 21 2.1 The 1980s in the USA ......................................................................................................... -

WHITNEY Education

WHITNEY Education Jenny Holzer: PROTECT PROTECT March 12 - May 31, 2009 Pre- and Post-Visit Materials for Teachers How can these materials be used? These materials provide a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts. I. About the Artist II. About the Exhibition III. Pre-Visit Activities IV. Post-Visit Activities V. Bibliography & Links What grade levels are these Pre- and Post-Visit materials intended for? These lessons and activities have been written for High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs. Please note that a portion of the exhibition includes declassified and other sensitive government documents that reference war, detainees, torture, homicide, filial relationships, arms, and the oil trade. There is adult language in the exhibition. We recommend that you visit the museum in advance of bringing your students to prepare for questions that might arise from the exhibition's content. We are happy to send you an Educator pass so that you can preview the exhibition. Please email [email protected] if you would like to request one. At the Museum Guided Visits We invite you and your students to visit the Whitney. To schedule a guided tour, please visit www.whitney.org/education. If you are scheduled for a guided school group tour, your museum educator will contact you prior to your visit. -

Jenny Holzer.Pdf

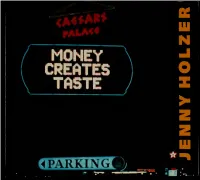

rAi*<« MONEY H : *: l i * TASTE SPARKING JENNY HOLZER OLZ Diane Waldman Chiat This exhibition is supported in part by generous funds from Jay and the National Endowment for the Arts Additional assistance has been provided by The Owen Cheatham Foundation, The Merrill G and the Arts Emita E. Hastings Foundation, the New York State Council on and anonymous donors SOLO/WON R. GUGGENHEIM AAUSEUAA, NEW YORK HARRY N. ABRAAAS, INC., PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK Published by The Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, Jenny Holzer Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York New York, in association with Harry N Abrams, Incorporated. December 12, 1989-February 11, 1990 New York, a Times Mirror Company. Project organization and production Copyright g 1989 by The Solomon R. Guggenheim Curator Foundation. New York Diane Waldman Coordination and Research Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clare Bell Waldman, Diane Editorial Jenny Holzer Carol Fuerstem Diana Murphy Catalog of an exhibition Includes bibliographical references Design 1 Holzer, Jenny, 1950- -Exhibitions Malcolm Grear Designers I Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum II. Title Special Photography N6537H577A4 1989 709'. 2 89-25747 David Heald ISBN 0-89207-068-4 Project Financial Management Heidi Olson cover Installation Sunrise Systems, Inc. Selections from Truisms 1986 Myro Riznyck Dectronic Starburst double-sided electronic display signboard, Scott Wixon 20 x 40' Timothy Ross Installation, Caesar's Palace, Las Vegas Guggenheim Operations and Maintenance Staff Lara Rubin, assistant to Jenny Holzer Organized -

Efficient Dynamics

A subsidiary of BMW AG BMW U.S. Press Information For Release: April 24th, 2014 Contact: Stacy Morris Corporate Communications Manager – Marketing and Culture 201-594-3360 / [email protected] Dr. Thomas Girst Head of Cultural Engagement +49 89-382-24753 / [email protected] First comprehensive publication about the BMW Art Car Collection to launch in the US. Woodcliff Lake, N.J. – April 24th, 2014 . The BMW Group and publisher Hatje Cantz are pleased to announce the launch of the first comprehensive publication about the legendary BMW Art Cars in the US. The book will first be presented at the Art Fair Paris Photo Los Angeles on April 24, 2014 and will be available on amazon.com for $45.00 as of early June 2014 (ISBN 9789775799458). On 195 pages the richly illustrated book presents a unique overview of the history of this automotive collection, launched in 1975, and designed by major modern and contemporary artists. Various portraits and interviews provide an insight into their creative processes while giving a descriptive account of the historical development of the collection. For over 40 years, the BMW Art Car Collection has fascinated art and design enthusiasts as well as lovers of cars and technology all over the world with its unique combination of fine art and innovative automobile technology. The collection first started when French race car driver and art aficionado Hervé Poulain, together with Jochen Neerpasch, then BMW Motorsport Director, asked his artist friend Alexander Calder to design an automobile. The result was a BMW 3.0 CSL which in 1975 competed in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, where it quickly became the crowd’s favorite: the birth of the BMW Art Car Collection. -

Jenny Holzer: Thing Indescribable

Press release Opening March 22, 2019 Jenny Holzer: Thing Indescribable Sponsored by Fundación BBVA’s commitment to generating new knowledge and to promoting and disseminating the most innovative contemporary creation is the hallmark of our ties with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao as a Strategic Trustee from its very inception. Fundación BBVA is very pleased to contribute its support to the organization of the extraordinary show Jenny Holzer. Thing Indescribable, which focuses on one of the most important conceptual artists on the international scene. Holzer’s work merges concepts and words in an output that questions not only reality but also the messages we receive on this reality in which we live. The exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao pays tribute to Holzer’s career, from her start in the mid-1970s, when her art sprang up on the streets of New York—surprising pedestrians with her Truisms—through four decades of her career, in which art, poetry, politics, and recent history converge in extraordinary, intellectually profound works boasting an exceptional artistic dimension. Her works oftentimes take on the form of installations in dialogue with the specific sites housing them. This extensive period which the show covers reflects her position as one of the most influential and recognized artists worldwide, who has earned numerous distinctions and awards, such as the Golden Lion at the 1990 Venice Biennale. With remarkable boldness and a critical sense, Holzer addresses social issues which often entail profound questions, resorting even to humor to facilitate the interpretation of messages which, at times, can be extremely harsh. I am pleased to have offered our sponsorship to such dazzling and reflective exhibition as this one, which highlights the greatness of Jenny Holzer’s art. -

Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women's Art in the US

Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY 860 11th Avenue, New York, NY 10019 For Immediate Release: THE UN-HEROIC ACT: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women's Art in the U.S. curated by Monika Fabijanska September 4 – November 2, 2018 Events: Opening reception: Sept. 12, 5:30-8:30 PM First artists talk: Sept. 26, 6-8 PM Symposium: Oct. 3, 5-9 PM Second artists talk: Oct. 24, 6-8 PM Naima Suzanne Lacy, Three Weeks in May, 1977, paper, ink ©1977. Suzanne Lacy. Courtesy of the artist. New York, NY, September 4, 2018 – The Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY announces the public programming for the groundbreaking exhibition The Un-Heroic Act: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women’s Art in the U.S. The exhibition will be on view at 860 Eleventh Avenue (between 58th & 59th Street, ground floor), New York, NY 10019, from September 4 to November 2, 2018, Mon-Fri 10-6. The opening reception will be held on Wednesday, September 12, from 5:30-8:30 PM. The exhibition, curated by Monika Fabijanska, will be accompanied by a catalog and public programming, including a symposium on October 3, 5-9 PM in the Moot Court, John Jay College, as well as exhibition tours and artist talks on September 26 and October 24, 6-8 PM in the gallery. The Un-Heroic Act is a concentrated survey of works by a diverse roster of artists representing three generations – and including Jenny Holzer, Suzanne Lacy, Ana Mendieta, Senga Nengudi, Yoko Ono, and Kara Walker – which aims to fill a gap in the history of art, where the subject of rape has been represented by countless historical depictions by male artists.