Conductor's Orders [Conductor Simone Young]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Fadi Kheir Fadi LETTERS from the LEADERSHIP

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Fadi Kheir Fadi LETTERS FROM THE LEADERSHIP The New York Philharmonic’s 2019–20 season certainly saw it all. We recall the remarkable performances ranging from Berlioz to Beethoven, with special pride in the launch of Project 19 — the single largest commissioning program ever created for women composers — honoring the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Together with Lincoln Center we unveiled specific plans for the renovation and re-opening of David Geffen Hall, which will have both great acoustics and also public spaces that can welcome the community. In March came the shock of a worldwide pandemic hurtling down the tracks at us, and on the 10th we played what was to be our final concert of the season. Like all New Yorkers, we tried to come to grips with the life-changing ramifications The Philharmonic responded quickly and in one week created NY Phil Plays On, a portal to hundreds of hours of past performances, to offer joy, pleasure, solace, and comfort in the only way we could. In August we launched NY Phil Bandwagon, bringing live music back to New York. Bandwagon presented 81 concerts from Chris Lee midtown to the far reaches of every one of the five boroughs. In the wake of the Erin Baiano horrific deaths of Black men and women, and the realization that we must all participate to change society, we began the hard work of self-evaluation to create a Philharmonic that is truly equitable, diverse, and inclusive. The severe financial challenge caused by cancelling fully a third of our 2019–20 concerts resulting in the loss of $10 million is obvious. -

My Fifty Years with Wagner

MY FIFTY YEARS WITH RICHARD WAGNER I don't for a moment profess to be an expert on the subject of the German composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner and have not made detailed comments on performances, leaving opinions to those far more enlightened than I. However having listened to Wagnerian works on radio and record from the late 1960s, and after a chance experience in 1973, I have been fascinated by the world and works of Wagner ever since. I have been fortunate to enjoy three separate cycles of Der Ring des Nibelungen, in Bayreuth 2008, San Francisco in 2011 and Melbourne in 2013 and will see a fourth, being the world's first fully digitally staged Ring cycle in Brisbane in 2020 under the auspices of Opera Australia. I also completed three years of the degree course in Architecture at the University of Quensland from 1962 and have always been interested in the monumental buildings of Europe, old and new, including the opera houses I have visited for performance of Wagner's works. It all started in earnest on September 29, 1973 when I was 28 yrs old, when, with friend and music mentor Harold King of ABC radio fame, together we attended the inaugural orchestral concert given at the Sydney Opera House, in which the legendary Swedish soprano Birgit Nilsson opened the world renowned building singing an all Wagner programme including the Immolation scene from Götterdämmerung, accompanied by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by a young Charles Mackerras. This event fully opened my eyes to the Ring Cycle - and I have managed to keep the historic souvenir programme. -

Impact Report 2019 Impact Report

2019 Impact Report 2019 Impact Report 1 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report “ Simone Young and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s outstanding interpretation captured its distinctive structure and imaginative folkloric atmosphere. The sumptuous string sonorities, evocative woodwind calls and polished brass chords highlighted the young Mahler’s distinctive orchestral sound-world.” The Australian, December 2019 Mahler’s Das klagende Lied with (L–R) Brett Weymark, Simone Young, Andrew Collis, Steve Davislim, Eleanor Lyons and Michaela Schuster. (Sydney Opera House, December 2019) Photo: Jay Patel Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report Table of Contents 2019 at a Glance 06 Critical Acclaim 08 Chair’s Report 10 CEO’s Report 12 2019 Artistic Highlights 14 The Orchestra 18 Farewelling David Robertson 20 Welcome, Simone Young 22 50 Fanfares 24 Sydney Symphony Orchestra Fellowship 28 Building Audiences for Orchestral Music 30 Serving Our State 34 Acknowledging Your Support 38 Business Performance 40 2019 Annual Fund Donors 42 Sponsor Salute 46 Sydney Symphony Under the Stars. (Parramatta Park, January 2019) Photo: Victor Frankowski 4 5 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report 2019 at a Glance 146 Schools participated in Sydney Symphony Orchestra education programs 33,000 Students and Teachers 19,700 engaged in Sydney Symphony Students 234 Orchestra education programs attended Sydney Symphony $19.5 performances Orchestra concerts 64% in Australia of revenue Million self-generated in box office revenue 3,100 Hours of livestream concerts -

2018–19 Chronological Listing

UPDATED June 7, 2019 CHRONOLOGICAL LISTING 2018–19 SEASON THE ART OF THE SCORE Alec Baldwin, Artistic Advisor THERE WILL BE BLOOD David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center Wednesday, September 12, 2018, 7:30 p.m. Thursday, September 13, 2018, 7:30 p.m. Hugh Brunt*, conductor Michelle Kim, violin Jonny GREENWOOD There Will Be Blood (score performed live to complete film) THE ART OF THE SCORE Alec Baldwin, Artistic Advisor 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center Friday, September 14, 2018, 8:00 p.m. Saturday, September 15, 2018, 8:00 p.m. André de Ridder, conductor Musica Sacra, chorus Kent Tritle, director VARIOUS 2001: A Space Odyssey (score performed live to complete film) (includes selections from works by Ligeti, R. Strauss, J. Strauss II, and Khachaturian) * New York Philharmonic debut JAAP VAN ZWEDEN CONDUCTS: OPENING GALA CONCERT NEW YORK, MEET JAAP David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center Thursday, September 20, 2018, 7:00 p.m. Jaap van Zweden, conductor Daniil Trifonov, piano Rebekah Heller*, bassoon Nate Wooley*, trumpet Brandon Lopez*, bass Constellation Chor*, moving voices Marisa Michelson, director César Alvarez*, Lilleth Glimcher*, staging and dramaturgy Brandon Clifford*, Wes McGee*, Johanna Lobdell*, matter design Marika Kent*, lighting design Tolulope Aremu*, costume design Ashley FURE Filament (World Premiere–New York Philharmonic Commission) RAVEL Piano Concerto in G major STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring * New York Philharmonic debut JAAP VAN ZWEDEN CONDUCTS: NEW WORK BY ASHLEY FURE, DANIIL TRIFONOV IN BEETHOVEN, AND STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center Friday, September 21, 2018, 8:00 p.m. -

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2019-20

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2019-20 2019-20 03 The Sydney Opera House stands on Tubowgule, Gadigal country. We acknowledge the Gadigal, the traditional custodians of this place, also known as Bennelong Point. First Nations readers are advised that this document may contain the names and images of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are now deceased. Sydney Opera House. Photo by Hamilton Lund. Front Cover: A single ghost light in the Joan Sutherland Theatre during closure (see page 52). Photo by Daniel Boud. Contents 05 About Us Financials & Reporting Who We Are 08 Our History 12 Financial Overview 100 Vision, Mission and Values 14 Financial Statements 104 Year at a Glance 16 Appendix 160 Message from the Chairman 18 Message from the CEO 20 2019-2020: Context 22 Awards 27 Acknowledgements & Contacts The Year’s Our Partners 190 Activity Our Donors 191 Contact Information 204 Trade Marks 206 Experiences 30 Index 208 Performing Arts 33 Precinct Experiences 55 The Building 60 Renewal 61 Operations & Maintenance 63 Security 64 Heritage 65 People 66 Team and Capability 67 Supporters 73 Inspiring Positive Change 76 Reconciliation Action Plan 78 Sustainability 80 Access 81 Business Excellence 82 Organisation Chart 86 Executive Team 87 Corporate Governance 90 Joan Sutherland Theatre foyers during closure. Photo by Daniel Boud. About Us 07 Sydney Opera House. Photo by by Daria Shevtsova. by by Photo Opera House. Sydney About Us 09 Who We Are The Sydney Opera House occupies The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the value of the Opera House’s online presence and programming a unique place in the cultural to our artists and communities, and increased the “It stands by landscape. -

Shostakovich & Tchaikovsky

Tchaikovsky Symphony No.5 MORNING SYMPHONY SERIES Thu 4 July 2019, 11am Perth Concert Hall Shostakovich & Tchaikovsky MASTERS SERIES Fri 5 & Sat 6 July 2019, 7.30pm Perth Concert Hall West Australian Symphony Orchestra and Wesfarmers Arts, creating the spark that sets off a lifelong love of music. Shigeru Komatsu – WASO Cello The West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Elders of the Indigenous Nations across Western Australia and on whose Lands we work. MORNING SYMPHONY SERIES Tchaikovsky Symphony No.5 ESA-PEKKA SALONEN Nyx (19 mins) TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No.5 (47 mins) Andante – Allegro con anima Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza Valse (Allegro moderato) Finale (Andante maestoso – Allegro vivace) Hendrik Vestmann conductor Wesfarmers Arts Pre-concert Talk Find out more about the music in the concert with this week’s speaker, Alan Lourens, Head of the Conservatorium of Music at The University of Western Australia (see page 15 for his biography). The Pre-concert Talk will take place at 9.40am in the Auditorium. Listen to WASO This performance is recorded for broadcast on ABC Classic on Friday, 12 July at 1pm AWST (or 11am online). For further details visit abc.net.au/classic 3 MASTERS SERIES Shostakovich & Tchaikovsky ESA-PEKKA SALONEN Nyx (19 mins) SHOSTAKOVICH Cello Concerto No.1 (31 mins) Allegretto Moderato – Cadenza – Allegro con moto Interval (25 mins) TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No.5 (47 mins) Andante – Allegro con anima Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza Valse (Allegro moderato) Finale (Andante maestoso – Allegro vivace) Hendrik Vestmann conductor Narek Hakhnazaryan cello Wesfarmers Arts Pre-concert Talk Find out more about the music in the concert with this week’s speaker, Alan Lourens, Head of the Conservatorium of Music at The University of Western Australia (see page 15 for his biography). -

GATEWAY GENEROUS DONORS RECOGNISED Letter to the Editor ‘Your Article on Food at Trinity Reminded Me of How Syd Wynne’S Kitchen Prepared Me for Life in India

No 85 November 2016 The Magazine of Trinity College, The University of Melbourne GATEWAY GENEROUS DONORS RECOGNISED Letter to the Editor ‘Your article on food at Trinity reminded me of how Syd Wynne’s kitchen prepared me for life in India. In 1964 I was the most junior tutor, the one whose duty it was to grind the SCR coffee beans. One night I had occasion to visit the kitchen, so I opened the door, turned on the light and watched as the place became alive with little black oblong shapes scuttling for the nearest shade. The following year I became a lecturer at Madras Christian College, with a flat to live in complete with a small kitchen and my very own cook/bearer. This kitchen, too, was alive with cockroaches, but thanks to Trinity caused me no discomfort, as I was already familiar with harmless kitchen wildlife.’ Ian Manning (TC 1963) We would love to hear what you think. Email the Editor at [email protected] Don Grilli, Chef Extraordinaire, 1962 JOIN YOUR NETWORK Trinity has over 23,000 alumni in more than 50 countries. This global network puts you in touch with lawyers, doctors, consultants, engineers, musicians, theologians, architects and many more. You Founded in 1872 as the first college of the University of can organise work experience for students, internships or act as a Melbourne, Trinity College is a unique tertiary institution mentor for students or young alumni. Expand your business contacts that provides a diverse range of rigorous academic programs via our LinkedIn group. -

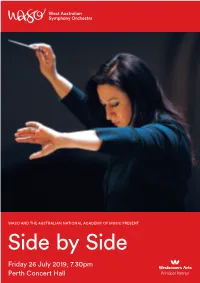

2019 Side by Side with ANAM

WASO AND THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MUSIC PRESENT Side by Side Friday 26 July 2019, 7.30pm Perth Concert Hall The West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Elders of the Indigenous Nations across Western Australia and on whose Lands we work. SPECIAL EVENT West Australian Symphony Orchestra and the Australian National Academy of Music present Side by Side PROKOFIEV Selections from Romeo and Juliet (31 mins) Introduction to Act 1 (Act 1, No.1) Dance of the Knights (Act 1, No.13) Introduction to Act 3 (Act 3, No.37) Dance of the Five Couples (Act 2, No.24) The Festival Continues (Act 2, No.30) Mercutio (Act 1, No.15) Romeo Avenges Mercutio’s Death (Act 2, No.35) The Fight (Act 1, No.6) Finale to Act 2 (Act 2, No.36) Juliet’s Funeral (Act 3, No.51) Death of Juliet (Act 3, No.52) Interval (20 mins) SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.7 Leningrad (80 mins) Allegretto Moderato (poco allegretto) Adagio – Moderato risoluto – Adagio – Allegro non troppo – Moderato Simone Young conductor ANAM and Simone Young are supported by the Minderoo Foundation. Wesfarmers Arts Pre-concert Talk Find out more about the music in the concert with this week’s speaker. The Pre-concert Talk will take place at 6.45pm in the Terrace Level Foyer. Listen to WASO This performance is recorded for broadcast on ABC Classic on Sunday, 4 August 2019 at 12pm AWST (or 10am online). For further details visit abc.net.au/classic 2 About The Artists Photo: Philipp Rathmer Philipp Photo: Photo: Cameron Jamieson Cameron Photo: Simone Young AM Australian National Conductor Academy of Music (ANAM) Simone Young AM, has been General The Australian National Academy of Manager and Music Director of the Music (ANAM) is dedicated to training Hamburg State Opera, Music Director the most exceptional young musicians of the Philharmonic State Orchestra from Australia and New Zealand. -

Sydney Symphony Fellowship

2020 IMPACT REPORT “ The concert marked the SSO’s return to its former home... the Sydney Town Hall is an attractive venue: easy to get to, grandly ornate, and nostalgic for those who remember the SSO’s concerts there in earlier years. The Victorian-era interior was spectacular... and it had a pleasing “big hall” acoustic that will lend grandeur and spaciousness to the SSO’s concerts of orchestral masterworks.” The Australian, 2020 2 Ben Folds, The Symphonic Tour, in Sydney Town Hall (March 2020). Photo: Christie Brewster 3 2020: A TRUE ENSEMBLE PERFORMANCE On 13 March 2020, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra was silenced for the first time in its 89-year history by the global COVID-19 pandemic. Andrew Haveron performing Tim Stevenson’s 4 Elegies as part of the Sydney Symphony at Home series. Filmed by Jay Patel The year had started boldly, with the Orchestra With a forward path identified, the Orchestra In August, Chief Conductor Designate Simone opening its 2020 Season in Sydney Town Hall quickly pivoted to digital concert production Young braved international travel restrictions as its temporary home for two years while the and expanded its website into an online concert and a two-week hotel quarantine to travel to Sydney Opera House Concert Hall was renovated. gallery. Starting in April, the Orchestra delivered Sydney and lead the musicians in their first Thirty-four season performances had already 29 Sydney Symphony at Home performances, full-group musical activities since lockdown. taken place by the time COVID-19 emerged. four Cuatro performances with the Sydney Dance There were tears of joy and relief as instruments However, that morning’s sold-out performance of Company, 18 Chamber Sounds performances were raised under her baton for rehearsals Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade would turn out recorded live at City Recital Hall with a focus and recordings at City Recital Hall and in to be the Orchestra’s final performance for 2020. -

Prokofiev CHANDOS

CHAN 10347(2) Wide cover 10/21/05 2:05 PM Page 1 Prokofiev CHANDOS CHAN 10347(2) CHAN 10347 BOOK.qxd 15/9/06 1:11 pm Page 2 Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891–1953) Peter Joslin Collection Peter premiere recording in English The Love for Three Oranges An opera in four acts and a prologue. Libretto by the composer, for Vsevolod Meyerhold’s adaptation of L’amore delle tre melarance by Carlo Gozzi English version by Tom Stoppard A production by Opera Australia recorded live at the Sydney Opera House in February 2005 Opera Australia Chorus Michael Black chorus master Francis Greep assistant chorus master Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra Stephen Mould assistant conductor Aubrey Murphy concert master Richard Hickox Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev 3 CHAN 10347 BOOK.qxd 15/9/06 1:11 pm Page 4 The King of Clubs....................................................................................................................Bruce Martin bass The Prince, his son..........................................................................................................John Mac Master tenor Clarissa, niece of the King......................................................................................Deborah Humble contralto Branco Gaica Leandro, the Prime Minister...............................................................................Teddy Tahu Rhodes baritone Truffaldino, who makes people laugh........................................................................William Ferguson tenor Pantaloon, the King’s confidant.....................................................................................Warwick -

Symphony Summer2020 Women Conductors

SUMMER 2020 n $6.95 symphonyTHE MAGAZINE OF THE LEAGUE OF AMERICAN ORCHESTRAS Where We Are Now Orchestras are seeking new ways forward amid the global pandemic and concerns about racial injustice Orchestras and Pandemics: Women Conductors Anti-Black Discrimination 1918 and 2020 On the Rise at U.S. Orchestras It’s About Time Gemma New, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra’s principal guest conductor, leads the DSO at Meyerson Symphony Center. Sylvia Elzafon The good news: more women are getting high-profile jobs conducting orchestras. The bad news: it’s not yet time to retire the phrase “glass ceiling” for once and for all. Will we get there, and if so, when? by Jennifer Melick n 2016, a ten-year-old violinist named St. Louis Symphony’s blog, “She has so Madeline de Geest went to a St. Louis much energy and potential. She reminded ISymphony Youth Orchestra concert me of myself when I was that age.” Since led by Gemma New, who had just been then, De Geest joined the SLSYO as one appointed the St. Louis Symphony’s resi- of its youngest musicians, and New’s pro- dent conductor. De Geest, enthralled, file has continued to rise. In addition to came backstage after the performance to her St. Louis position, which concluded in ask for an autograph, and New gave the May, New is now principal guest conduc- young musician her conducting baton. In tor at the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, the 2017, New invited De Geest to a St. Louis first woman to hold that title there; serves Symphony Youth Orchestra rehearsal, and as music director of Canada’s Hamilton De Geest brought her violin and music Philharmonic Orchestra; and has a full folder. -

WILLIAM TELL Armando Noguera (William Tell) VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS WILLIAM TELL

GIOACHINO ROSSINI WILLIAM TELL Armando Noguera (William Tell) VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS WILLIAM TELL Composer Gioachino Rossini Librettists V.J Etienne de Jouy and H.L.F. Bis Conductor Richard Mills AM Director Rodula Gaitanou Set and Lighting Designer Simon Corder Costume Designer Esther Marie Hayes Assistant Director Meg Deyell CAST Guillaume Tell Armando Noguera Rodolphe Paul Biencourt Arnold Melcthal Carlos E. Bárcenas Ruodi Timothy Reynolds Walter Furst Jeremy Kleeman Leuthold Jerzy Kozlowski Melcthal Teddy Tahu Rhodes Mathilde Gisela Stille Jemmy Alexandra Flood Hedwige Liane Keegan Gesler Paolo Pecchioli* Orchestra Victoria 14, 17 and 19 JULY 2018 Palais Theatre, St Kilda Original premiere 3 August 1829, Paris Opera Running Time is 3 hours and 15 minutes, including interval Sung in French with English surtitles *Paolo Pecchioli appears with the support of the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne. 3 PRODUCTION PRODUCTION TEAM Production Manager Eduard Inglés Stage Manager Marina Milankovic Deputy Stage Manager Meg Deyell Assistant Stage Manager Jessica Frost Assistant Stage Manager Luke Hales Wardrobe Supervisor Kate Glenn-Smith MUSIC STAFF Principal Repetiteur Phoebe Briggs Chorus Preparation Richard Mills, Phoebe Briggs Repetiteur Phillipa Safey CHORUS Soprano Jordan Auld*, Kirilie Blythman, Jesika Clark*, Rosie Cocklin*, Alexandra Ioan, Millie Leaver*, Rebecca Rashleigh, Diana Simpson, Emily Uhlrich, Nicole Wallace Mezzo Soprano Kerrie Bolton, Shakira Dugan, Jessie Eastwood*, Kristina Fekonja*, Hannah Kostros*,