064-069 Rosenwinkel 0805

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rosenwinkel Introductions

The Rosenwinkel Introductions: Stylistic Tendencies in 10 Introductions Recorded by Jazz Guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel Jens Hoppe A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I, Jens Hoppe, hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: ______________________________________________Date: 31 March 2016 i Acknowledgments The task of writing a thesis is often made more challenging by life’s unexpected events. In the case of this thesis, it was burglary, relocation, serious injury, marriage, and a death in the family. Disruptions also put extra demands on those surrounding the writer. I extend my deepest gratitude to the following people for, above all, their patience and support. To my supervisor Phil Slater without whom this thesis would not have been possible – for his patience, constructive comments, and ability to say things that needed to be said in a positive and encouraging way. Thank you Phil. To Matt McMahon, who is always an inspiration, whether in conversation or in performance. To Simon Barker, for challenging some fundamental assumptions and talking about things that made me think. To Troy Lever, Abel Cross, and Pete ‘Göfren’ for their help in the early stages. They are not just wonderful musicians and friends, but exemplary human beings. To Fletcher and Felix for their boundless enthusiasm, unconditional love and the comic relief they provided. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

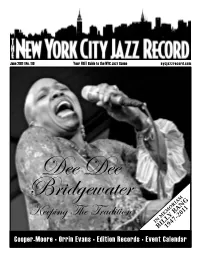

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Gerry Teekens, Whose Criss Cross Label Was a Harbor to Several Jazz Generations, Dies at 83

♫ Donate Live Stream · WBGO LOADING... Saturday Afternoon Jazz On the Air Music News Listen & Connect Calendars & Events Support About Search Gerry Teekens, Whose Criss Cross Label Was a Harbor to Several Jazz Generations, Dies at 83 By DAVID R. ADLER • NOV 6, 2019 ! Twitter " Facebook # Google+ $ Email LEO VAN VELZEN / LEOVANVELZEN.COM Gerry Teekens, founder and proprietor of Criss Cross Jazz, an unassuming Dutch indie label that became a vital repository of recorded jazz from the 1980s onward, died on Oct. 31. He was 83. His death was confirmed by his son, Jerry Teekens, Jr. At the news, tributes poured in from Criss Cross artists old and new, including soprano saxophonist Sam Newsome and guitarist David Gilmore. Formerly a professional drummer, Teekens founded Criss Cross in 1981 with a mission to document swinging, straight-ahead jazz of the highest caliber. At first the roster featured musicians as revered as guitarist Jimmy Raney and saxophonist Warne Marsh, but it grew to include the young and the promising: saxophonists Kenny Garrett, Chris Potter and Mark Turner, to name but a few, and pianists Orrin Evans, Bill Charlap and Benny Green. Countdown Watch later Share Multiple times a year, Teekens would cross the ocean from Enschede, Netherlands (thus the Criss Cross name), taking up at Rudy Van Gelder’s famed studio in New Jersey (and later at Systems Two in Brooklyn) for a full week of recording — knocking out an album a day, in the old-school way. In recent years the Criss Cross aesthetic began to broaden, with artists like alto saxophonist David Binney and trumpeter Alex Sipiagin using electronics and synthesizers, moving beyond the strictures of one-take-and-done while still remaining on board with the label. -

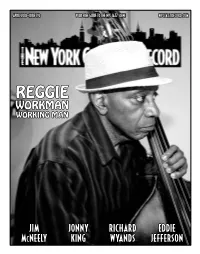

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

John Mcneil Bill Mchenry

John McNeil John McNeil is regarded as one of the most original and creative jazz artists in the world today. For nearly three decades John has toured with his own groups and has received widespread acclaim as both a player and composer. His highly personal trumpet style communicates across the full range of contemporary jazz, and his compositions combine harmonic freedom with melodic accessibility. John's restless experimentation has kept him on the cutting edge of new music. His background includes the Horace Silver Quintet, Gerry Mulligan, and the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. John is equally at home in free and structured settings, and this versatility has put him on stage with artists from Slide Hampton to John Abercrombie. John McNeil was born in 1948 in northern California. Due to a lack of available musical instruction in his home town of Yreka, John largely taught himself to play trumpet and read music. By the time he graduated from high school in 1966, John had already begun playing professionally in the northern California region. John moved to New York in the mid-1970's and began a freelance career. His reputation as an innovative trumpet voice began to grow as he played with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, and led his own groups at clubs such as Boomer's, the legendary Village jazz room. In the late 70's, John joined the Horace Silver Quintet. Around the same time, he began recording for the SteepleChase label under his own name and toured internationally. Although he has worked as a sideman with such luminaries as Gerry Mulligan, John has consistently led his own groups from about 1980 to the present. -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

Joshua Redman Bio

JOSHUA REDMAN BIO Joshua Redman is one of the most acclaimed and charismatic jazz artists to have emerged in the decade of the 1990s. Born in Berkeley, California, he is the son of legendary saxophonist Dewey Redman and dancer Renee Shedroff. He was exposed at an early age to a variety of musics (jazz, classical, rock, soul, Indian, Indonesian, Middle-Eastern, African) and instruments (recorder, piano, guitar, gatham, gamelan), and began playing clarinet at age nine before switching to what became his primary instrument, the tenor saxophone, one year later. The early influences of John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cannonball Adderley and his father, Dewey Redman, as well as The Beatles, Aretha Franklin, the Temptations, Earth, Wind and Fire, Prince, The Police and Led Zeppelin drew Joshua more deeply into music. But although Joshua loved playing the saxophone and was a dedicated member of the award-winning Berkeley High School Jazz Ensemble and Combo from 1983-86, academics were always his first priority, and he never seriously considered becoming a professional musician. In 1991 Redman graduated from Harvard College summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa with a B.A. in Social Studies. He had already been accepted by Yale Law School, but deferred entrance for what he believed was only going to be one year. Some of his friends (former students at the Berklee College of Music whom Joshua had met while in Boston) had recently relocated to Brooklyn, and they were looking for another housemate to help with the rent. Redman accepted their invitation to move in, and almost immediately he found himself immersed in the New York jazz scene. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

Keeping the Tradition by Marilyn Lester © 2 0 1 J a C K V

AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM P EE ING TK THE R N ADITIO DARCY ROBERTA JAMES RICKY JOE GAMBARINI ARGUE FORD SHEPLEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : ROBERTA GAMBARINI 6 by ori dagan [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : darcy james argue 7 by george grella General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : preservation hall jazz band 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ricky ford by russ musto Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : joe shepley 10 by anders griffen [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : weekertoft by stuart broomer US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 31 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Event Calendar 32 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mathieu Bélanger, Marco Cangiano, Ori Dagan, George Grella, George Kanzler, Annie Murnighan Contributing Photographers “Tradition!” bellowed Chaim Topol as Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof.