2017 American College of Rheumatology/American Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rheumatology?

WHAT IS RHEUMATOLOGY? diseases affect nearly 50 million Americans and can cause joint and organ destruction, severe pain, disability and even death. Inflammatory rheumatic diseases with arthritis cause more disability in America than heart disease, cancer or diabetes. How can a Rheumatologist help? Most rheumatologic conditions previously led to severe disability and even death in many patients. Evidence-based medical treatment of rheumatological disorders is currently helping patients with rheumatism lead a near-normal life. Medications such as Methotrexate and Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors have had a significant impact on patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), and today patients with RA can lead a pain free and productive life. Rheumatology facts by numbers: • Over 7 million American adults suffer from inflam- matory rheumatic diseases; 1.3 million adults have rheumatoid arthritis; and 161,000 to 322,000 adults have lupus. • 8.4 percent of women will develop a rheumatic dis- heumatology is a rapidly ease during their lifetime. Women are 2 to 3 times R evolving subspecialty in more likely to be diagnosed with RA, and 10 times internal medicine and more likely to develop lupus than men. pediatrics which includes the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and • 5 percent of men in the U.S. will develop a rheu- management of over 100 complex inflammatory and matic disease during their lifetime. connective tissue diseases. Rheumatologists care for a wide • Osteoporosis and low bone mass are currently esti- array of patients – from children to senior citizens, see mated to be a major public health threat for almost diseases like Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus 44 million U.S. -

Resection Arthroplasty for Failed Shoulder Arthroplasty

J Shoulder Elbow Surg (2013) 22, 247-252 www.elsevier.com/locate/ymse Resection arthroplasty for failed shoulder arthroplasty Stephanie J. Muh, MDa, Jonathan J. Streit, MDb, Christopher J. Lenarz, MDa, Christopher McCrum, BSc, John Paul Wanner, BSa, Yousef Shishani, MDa, Claudio Moraga, MDd, Robert J. Nowinski, DOe, T. Bradley Edwards, MDf, Jon J.P. Warner, MDg, Gilles Walch, MDh, Reuben Gobezie, MDi,* aCase Shoulder and Elbow Service, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH, USA bDepartment of Orthopaedics, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH, USA cCase Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA dDepartment of Orthopedic Surgery, Clinica Alemana Santiago, Santiago, Chile eOrthoNeuro, New Albany, OH, USA fFondren Orthopedic Group, Houston, TX, USA gHarvard Shoulder Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA hCentre Orthopedique Santy, Shoulder Unit, Lyon, France iThe Cleveland Shoulder Institute, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH, USA Background: As shoulder arthroplasty becomes more common, the number of failed arthroplasties requiring revision is expected to increase. When revision arthroplasty is not feasible, resection arthroplasty has been used in an attempt to restore function and relieve pain. Although outcomes data for resection arthroplasty exist, studies comparing the outcomes after the removal of different primary shoulder arthro- plasties have been limited. Materials and methods: This was a retrospective multicenter review of 26 patients who underwent resection arthroplasty for failure of a primary arthroplasty at a mean follow-up of 41.8 months (range, 12-130 months). Resection arthroplasty was performed for 6 failed total shoulder arthroplasties (TSAs), 7 failed hemiarthro- plasties, and 13 failed reverse TSAs. -

Leflunomide-Arava-Fact-Sheet

Leflunomide PATIENT FACT SHEET (Arava) Leflunomide (Arava) is a drug approved to treat combination with other DMARDs. Leflunomide blocks the adults with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. formation of DNA, which is important for replicating cells, It belongs to a class of medications called disease such as those in the immune system. It suppresses the modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Leflunomide immune system to reduce inflammation that causes pain is often used to treat rheumatoid arthritis alone or in and swelling in rheumatoid arthritis. WHAT IS IT? Leflunomide is usually given as a 20 mg tablet once a the first 3 days after starting leflunomide. It may take day. Doctors will often prescribe a “loading dose” to be several weeks after starting leflunomide to experience an taken when the medicine is first prescribed. The loading improvement in joint pain or swelling. Complete benefits dose of leflunomide is usually 100 mg (or five 20 mg may not be experienced until 6 to 12 weeks after starting HOW TO tablets) once weekly for 3 weeks or 100 mg a day for the medication. TAKE IT The most common side effect of leflunomide is stomach pain, indigestion, rash, and hair loss. In fewer diarrhea, which occurs in approximately 20 percent than 10 percent of patients, leflunomide can cause of patients. This symptom frequently improves with abnormal liver function tests or decreased blood cell time or by taking a medication to prevent diarrhea. If or platelet counts. Rarely, this drug may cause lung diarrhea persists, the dose of leflunomide may need to problems, such as cough, shortness of breath or be reduced. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0209462 A1 Bilotti Et Al

US 20170209462A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0209462 A1 Bilotti et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 27, 2017 (54) BTK INHIBITOR COMBINATIONS FOR Publication Classification TREATING MULTIPLE MYELOMA (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: Pharmacyclics LLC, Sunnyvale, CA A 6LX 3/573 (2006.01) A69/20 (2006.01) (US) A6IR 9/00 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Elizabeth Bilotti, Sunnyvale, CA (US); A69/48 (2006.01) Thorsten Graef, Los Altos Hills, CA A 6LX 3/59 (2006.01) (US) A63L/454 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .......... A61 K3I/573 (2013.01); A61K 3 1/519 (21) Appl. No.: 15/252,385 (2013.01); A61 K3I/454 (2013.01); A61 K 9/0053 (2013.01); A61K 9/48 (2013.01); A61 K (22) Filed: Aug. 31, 2016 9/20 (2013.01) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein are pharmaceutical combinations, dosing Related U.S. Application Data regimen, and methods of administering a combination of a (60) Provisional application No. 62/212.518, filed on Aug. BTK inhibitor (e.g., ibrutinib), an immunomodulatory agent, 31, 2015. and a steroid for the treatment of a hematologic malignancy. US 2017/0209462 A1 Jul. 27, 2017 BTK INHIBITOR COMBINATIONS FOR Subject in need thereof comprising administering pomalido TREATING MULTIPLE MYELOMA mide, ibrutinib, and dexamethasone, wherein pomalido mide, ibrutinib, and dexamethasone are administered con CROSS-REFERENCE TO RELATED currently, simulataneously, and/or co-administered. APPLICATION 0008. In some aspects, provided herein is a method of treating a hematologic malignancy in a subject in need 0001. This application claims the benefit of U.S. -

[Product Monograph Template

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrXELJANZ® tofacitinib, tablets, oral 5 mg tofacitinib (as tofacitinib citrate) 10 mg tofacitinib (as tofacitinib citrate) PrXELJANZ® XR tofacitinib extended-release, tablets, oral 11 mg tofacitinib (as tofacitinib citrate) ATC Code: L04AA29 Selective Immunosuppressant Pfizer Canada ULC Date of Preparation: 17,300 Trans-Canada Highway October 24, 2019 Kirkland, Quebec H9J 2M5 TMPF PRISM C.V. c/o Pfizer Manufacturing Holdings LLC Pfizer Canada ULC, Licensee © Pfizer Canada ULC 2019 Submission Control No: 230976 XELJANZ/XELJANZ XR Page 1 of 80 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION.........................................................3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ........................................................................3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE..............................................................................3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ...................................................................................................4 ADVERSE REACTIONS..................................................................................................15 DRUG INTERACTIONS ..................................................................................................29 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION..............................................................................34 OVERDOSAGE ................................................................................................................38 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ............................................................38 -

Rheuma.Stamp Line&Box

Arthritis Mutilans: A Report from the GRAPPA 2012 Annual Meeting Vinod Chandran, Dafna D. Gladman, Philip S. Helliwell, and Björn Gudbjörnsson ABSTRACT. Arthritis mutilans is often described as the most severe form of psoriatic arthritis. However, a widely agreed on definition of the disease has not been developed. At the 2012 annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), members hoped to agree on a definition of arthritis mutilans and thus facilitate clinical and molecular epidemiological research into the disease. Members discussed the clinical features of arthritis mutilans and defini- tions used by researchers to date; reviewed data from the ClASsification for Psoriatic ARthritis study, the Nordic psoriatic arthritis mutilans study, and the results of a premeeting survey; and participated in breakout group discussions. Through this exercise, GRAPPA members developed a broad consensus on the features of arthritis mutilans, which will help us develop a GRAPPA-endorsed definition of arthritis mutilans. (J Rheumatol 2013;40:1419–22; doi:10.3899/ jrheum.130453) Key Indexing Terms: OSTEOLYSIS ANKYLOSIS PENCIL-IN-CUP SUBLUXATION FLAIL JOINT ARTHRITIS MUTILANS Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory musculoskeletal gists as a severe destructive form of PsA, a precise disease specifically associated with psoriasis. Moll and definition has not yet been universally accepted. The earliest Wright defined PsA as “psoriasis associated with inflam- definition of arthritis mutilans was provided -

Advanced Age Increases Immunosuppression in the Brain and Decreases Immunotherapeutic Efficacy in Subjects with Glioblastoma

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on June 16, 2020; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3874 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. RESEARCH ARTICLE Advanced Age Increases Immunosuppression in the Brain and Decreases Immunotherapeutic Efficacy in Subjects with Glioblastoma Authors: Erik Ladomersky1, Lijie Zhai1, Kristen L. Lauing1, April Bell1, Jiahui Xu2, Masha Kocherginsky2, Bin Zhang3,4, Jennifer D. Wu5, Joseph R. Podojil4, Leonidas C. Platanias3,6, Aaron Y. Mochizuki7, Robert M. Prins8, Priya Kumthekar9, Jeffrey J. Raizer9, Karan Dixit9, Rimas V. Lukas9, Craig Horbinski1,10, Min Wei11, Changyou Zhou11, Graham Pawelec12, Judith Campisi13,14, Ursula Grohmann15, George C. Prendergast16, David H. Munn17, Derek A. Wainwright1,5,7,8 Affiliations: 1Department of Neurological Surgery, 2Department of Preventive Medicine-Biostatistics, 3Department of Medicine-Hematology/Oncology, 4Department of Microbiology- Immunology, 5Department of Urology, 6Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, 9Department of Neurology, 10Department of Pathology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, USA. 7Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, USA. 8Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, USA. 11BeiGene, Zhong-Guan-Cun Life Science Park, Changping District, Beijing, China. 12Department of Immunology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. 13Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, CA, USA. 14Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA. 15Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy. 16Lankenau Institute for Medical Research, Wynnewood, PA, USA. 17Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta, GA, USA. Running Title: Aging and brain immunosuppression of GBM immunity Keywords: Senescence, neuroimmunology, immunotherapy, brain tumor, IDO COI: Min Wei and Changyou Zhou possess financial interests and are paid employees of BeiGene, Ltd. -

XELJANZ (Tofacitinib) XELJANZ XR (Tofacitinib Extended Release Tablets)

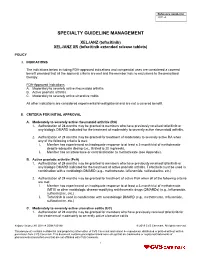

Reference number(s) 2011-A SPECIALTY GUIDELINE MANAGEMENT XELJANZ (tofacitinib) XELJANZ XR (tofacitinib extended release tablets) POLICY I. INDICATIONS The indications below including FDA-approved indications and compendial uses are considered a covered benefit provided that all the approval criteria are met and the member has no exclusions to the prescribed therapy. FDA-Approved Indications A. Moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis B. Active psoriatic arthritis C. Moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis All other indications are considered experimental/investigational and are not a covered benefit. II. CRITERIA FOR INITIAL APPROVAL A. Moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) 1. Authorization of 24 months may be granted to members who have previously received tofacitinib or any biologic DMARD indicated for the treatment of moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis. 2. Authorization of 24 months may be granted for treatment of moderately to severely active RA when any of the following criteria is met: i. Member has experienced an inadequate response to at least a 3-month trial of methotrexate despite adequate dosing (i.e., titrated to 20 mg/week). ii. Member has an intolerance or contraindication to methotrexate (see Appendix). B. Active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) 1. Authorization of 24 months may be granted to members who have previously received tofacitinib or any biologic DMARD indicated for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis. Tofacitinib must be used in combination with a nonbiologic DMARD (e.g., methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, etc.) 2. Authorization of 24 months may be granted for treatment of active PsA when all of the following criteria are met: i. -

JAK-Inhibitors for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: a Focus on the Present and an Outlook on the Future

biomolecules Review JAK-Inhibitors for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Focus on the Present and an Outlook on the Future 1, 2, , 3 1,4 Jacopo Angelini y , Rossella Talotta * y , Rossana Roncato , Giulia Fornasier , Giorgia Barbiero 1, Lisa Dal Cin 1, Serena Brancati 1 and Francesco Scaglione 5 1 Postgraduate School of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Milan, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (L.D.C.); [email protected] (S.B.) 2 Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Rheumatology Unit, AOU “Gaetano Martino”, University of Messina, 98100 Messina, Italy 3 Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology Unit, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico di Aviano (CRO), Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Pordenone, 33081 Aviano, Italy; [email protected] 4 Pharmacy Unit, IRCCS-Burlo Garofolo di Trieste, 34137 Trieste, Italy 5 Head of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology Unit, Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Department of Oncology and Onco-Hematology, Director of Postgraduate School of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Milan, 20162 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-090-2111; Fax: +39-090-293-5162 Co-first authors. y Received: 16 May 2020; Accepted: 1 July 2020; Published: 5 July 2020 Abstract: Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) belong to a new class of oral targeted disease-modifying drugs which have recently revolutionized the therapeutic panorama of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other immune-mediated diseases, placing alongside or even replacing conventional and biological drugs. -

Dissecting Intratumor Heterogeneity of Nodal B Cell Lymphomas on the Transcriptional, Genetic, and Drug Response Level

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/850438; this version posted December 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Dissecting intratumor heterogeneity of nodal B cell lymphomas on the 2 transcriptional, genetic, and drug response level 3 4 Tobias Roider1-3, Julian Seufert4-5, Alexey Uvarovskii6, Felix Frauhammer6, Marie Bordas4,7, 5 Nima Abedpour8, Marta Stolarczyk1, Jan-Philipp Mallm9, Sophie Rabe1-3,5,10, Peter-Martin 6 Bruch1-3, Hyatt Balke-Want11, Michael Hundemer1, Karsten Rippe9, Benjamin Goeppert12, 7 Martina Seiffert7, Benedikt Brors13, Gunhild Mechtersheimer12, Thorsten Zenz14, Martin 8 Peifer8, Björn Chapuy15, Matthias Schlesner4, Carsten Müller-Tidow1-3, Stefan Fröhling10,16, 9 Wolfgang Huber2,3, Simon Anders6*, Sascha Dietrich1-3,10* 10 11 1 Department of Medicine V, Hematology, Oncology and Rheumatology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, 12 Germany, 13 2 Molecular Medicine Partnership Unit (MMPU), Heidelberg, Germany, 14 3 European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), Heidelberg, Germany, 15 4 Bioinformatics and Omics Data Analytics, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany, 16 5 Faculty of Biosciences, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 17 6 Center for Molecular Biology of the University of Heidelberg (ZMBH), Heidelberg, Germany, 18 7 Division of Molecular Genetics, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany, 19 8 Department for Translational -

Rheumatology Connections

IN THIS ISSUE Uncommon Manifestations of SLE 3 | PACNS or RCVS? 6 | Psychosocial Burden of PsA 9 Advances in IL-6 Biology 10 | AHCT for Systemic Sclerosis 12 | PET in Large Vessel Vasculitis 14 Rheumatology Connections An Update for Physicians | Summer 2018 112236_CCFBCH_18RHE1077_ACG.indd 1 7/10/18 2:06 PM Dear Colleagues, Welcome to another issue of Rheumatology Con- From the Chair of Rheumatic nections. I think you’ll find our title perfectly apt as and Immunologic Diseases you browse these articles, full of connections to an array of other specialties, to our patients and to our clinical, scientific and educational missions. Dr. Chatterjee’s collaboration with the Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology for treating severe systemic sclerosis is but one example of the relevance of our field across disciplines (p. 12). Cleveland Clinic’s Rheumatology This issue also features a study of psychosocial fac- Program is ranked among the top tors in psoriatic arthritis co-authored by Dr. Husni 2 in the nation in U.S. News & and a colleague in the Neurological Institute (p. 9). World Report’s “America’s Best Our connections to neurology become even clearer Hospitals” survey. as Drs. Calabrese and Hajj-Ali offer guidance on distinguishing between a neurological condition and the more fatal, less common rheumatologic one that it mimics (p. 6). Rheumatology Connections, published by We are always searching for ways to transcend Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Rheumatic disciplinary boundaries to provide better patient care. Our multidisciplinary style of caring for patients was and Immunologic Diseases, provides information critical in a case co-authored with a colleague in pathology and Drs. -

The Case for Lupus Nephritis

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Expanding the Role of Complement Therapies: The Case for Lupus Nephritis Nicholas L. Li * , Daniel J. Birmingham and Brad H. Rovin Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; [email protected] (D.J.B.); [email protected] (B.H.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-614-293-4997; Fax: +1-614-293-3073 Abstract: The complement system is an innate immune surveillance network that provides defense against microorganisms and clearance of immune complexes and cellular debris and bridges innate and adaptive immunity. In the context of autoimmune disease, activation and dysregulation of complement can lead to uncontrolled inflammation and organ damage, especially to the kidney. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is characterized by loss of tolerance, autoantibody production, and immune complex deposition in tissues including the kidney, with inflammatory consequences. Effective clearance of immune complexes and cellular waste by early complement components protects against the development of lupus nephritis, while uncontrolled activation of complement, especially the alternative pathway, promotes kidney damage in SLE. Therefore, complement plays a dual role in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. Improved understanding of the contribution of the various complement pathways to the development of kidney disease in SLE has created an opportunity to target the complement system with novel therapies to improve outcomes in lupus nephritis. In this review, we explore the interactions between complement and the kidney in SLE and their implications for the treatment of lupus nephritis. Keywords: lupus nephritis; complement; systemic lupus erythematosus; glomerulonephritis Citation: Li, N.L.; Birmingham, D.J.; Rovin, B.H.