By Danne Honour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballistic Protective Properties of Material Representative of English Civil War Buff-Coats and Clothing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWE Bristol Research Repository International Journal of Legal Medicine (2020) 134:1949–1956 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-020-02378-x ORIGINAL ARTICLE Ballistic protective properties of material representative of English civil war buff-coats and clothing Brian May1 & Richard Critchley1 & Debra Carr1,2 & Alan Peare1 & Keith Dowen3 Received: 19 March 2020 /Accepted: 15 July 2020 / Published online: 21 July 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract One type of clothing system used in the English Civil War, more common amongst cavalrymen than infantrymen, was the linen shirt, wool waistcoat and buff-coat. Ballistic testing was conducted to estimate the velocity at which 50% of 12-bore lead spherical projectiles (V50) would be expected to perforate this clothing system when mounted on gelatine (a tissue simulant used in wound ballistic studies). An estimated six-shot V50 for the clothing system was calculated as 102 m/s. The distance at which the projectile would have decelerated from the muzzle of the weapon to this velocity in free flight was triple the recognised effective range of weapons of the era suggesting that the clothing system would provide limited protection for the wearer. The estimated V50 was also compared with recorded bounce-and-roll data; this suggested that the clothing system could provide some protection to the wearer from ricochets. Finally, potential wounding behind the clothing system was investigated; the results compared favourably with seventeenth century medical writings. Keywords Leather . Linen . Wool . Behind armour blunt trauma . -

I . the Color Gene C

THE ABC OF COLOR INHERITANCE IN HORSES W. E. CASTLE Division of Genetics, University of California, Berkeley, California Received October, 27, 1947 HE study of color inheritance in horses was begun in the early days of Tgenetics. Indeed many facts concerning it had already been established earlier, by DARWINin his book on “Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.” At irregular inteivals since then, new attempts have been made to collect and classify in terms of genetic factors the records contained in stud books concerning the colors of colts in relation to the colors of their sires and dams. A full bibliography is given by CREWand BuCHANAN-SMITH (19301. By such studies, we have acquired very full information as to what color a colt may be expected to have, when the color of its parents and grandparents is known. This knowledge is empirical rather than experimental in nature. For horses being slow breeding and expensive are rarely available for direct experi- mental study, such as can be made with the small laboratory mammals, mice, rats, rabbits and guinea pigs. We have definite information that color inheritance in horses involves the existence of mutant genes similar to those demonstrated by experimental studies to be involved in color inheritance of other mammals. But the horse genes have been given special names, as they were successively discovered, and it is difficult at present to correlate them with the better known names and geneic symbols used by the experimental breeders. The present paper is an attempt to make such a correlation. Just as in morphological studies comparative anatomy was found useful and still is used to establish homologies between systems of organs, so in mammalian genetics, a comparative study of gene action in the production of coat colors and color patterns may also be of value. -

Pinjarra Park Printable Form Guide

FREE printable form guides from www.punters.com.au Pinjarra Park Tuesday 25th April 2017 Race 1 PINJARRA RSL MAIDEN 1600m 1:09 pm Race 2 SOUND TELEGRAPH HANDICAP 1500m 1:44 pm Race 3 AURORA LANDSCAPING MAIDEN 1200m 2:19 pm Race 4 PINJARRA REAL ESTATE MAIDEN 1200m 2:54 pm Race 5 WORK CLOBBER MANDURAH MAIDEN 1000m 3:29 pm Race 6 SIGN STRATEGY HANDICAP 1000m 4:04 pm Race 7 WAROONA RURAL SERVICES HANDICAP 2000m 4:34 pm Race 8 RENEW IPL HANDICAP 1300m 5:10 pm Produced for free by Punters.com.au, thanks to William Hill Punters.com.au is your ultimate racing website. Social networking, free form guides, odds comparison, betting deals, the latest news, photos and a revolutionary tipping system allowing punters to buy and sell their horse racing tips. Visit www.punters.com.au for more information. © 2017 Punters Paradise Pty Ltd. If you're reading this copyright notice you're probably thinking of printing lots of copies. Go for it. Give a copy to your mates, your mum and some strangers at the TAB. We want people to have our free form guides. Just don't sell them, alter, change or reproduce parts of this form guide as it's strictly prohibited. While Punters.com.au takes all care in the preparation of information we accept no responsibility nor warrants the accuracy of the information displayed. © 2017 Racing Australia Pty Ltd (RA) (and other parties working with it). Racing materials, including fields, form and results are subject to copyright which is owned by RA and other parties working with it. -

Use of Genomic Tools to Discover the Cause of Champagne Dilution Coat Color in Horses and to Map the Genetic Cause of Extreme Lordosis in American Saddlebred Horses

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science Veterinary Science 2014 USE OF GENOMIC TOOLS TO DISCOVER THE CAUSE OF CHAMPAGNE DILUTION COAT COLOR IN HORSES AND TO MAP THE GENETIC CAUSE OF EXTREME LORDOSIS IN AMERICAN SADDLEBRED HORSES Deborah G. Cook University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cook, Deborah G., "USE OF GENOMIC TOOLS TO DISCOVER THE CAUSE OF CHAMPAGNE DILUTION COAT COLOR IN HORSES AND TO MAP THE GENETIC CAUSE OF EXTREME LORDOSIS IN AMERICAN SADDLEBRED HORSES" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gluck_etds/15 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Veterinary Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

The Occurrence of Silver Dilution in Horse Coat Colours

ISSN 1392-2130. VETERINARIJA IR ZOOTECHNIKA (Vet Med Zoot). T. 60 (82). 2012 THE OCCURRENCE OF SILVER DILUTION IN HORSE COAT COLOURS Erkki Sild, Sirje Värv and Haldja Viinalass Institute of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1, 51014 Tartu, Estonia; Tel: +372 731 3469; Fax: +372 742 2344; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The MC1R allele “e” in the homozygous state leads to the production of pheomelanin and is responsible for inhibition of expression of the silver dilution gene (PMEL17 “Z” allele). Horse coat colour is one of the traits breeders select for. A total of 133 horses representing Estonian Native (48), Estonian Heavy Draught (40) and Tori (45) breeds were genotyped for key polymorphisms at C901T in MC1R, the 11 bp deletion in ASIP and C1457T in PMEL17 to determine horse coat colour variation and selection possibilities to increase silver-diluted colours. Our genotyping results showed the “ee” genotype frequency in the MC1R gene to be as follows: Estonian Native 45.8%, Estonian Heavy Draught 65.0%, and Tori 77.8%, and the “Z_” genotype in PMEL17 to be 10.4%, 12.5%, and 0.0%, respectively. Six of total 133 horses with silver dilution were examined for MCOA. No eye abnormalities were detected. Considering the PMEL17 gene singly, silver coat colour could be expressed phenotypically in 12% of genotyped Estonian Heavy Draught horses, but due to unfavourable covariation with the MC1R “e” allele, it only occurred in two per cent of horses. Keywords: ASIP, horse coat colour, MC1R, MCOA, PMEL17, silver phenotype. -

Top 10 Birds for Raising Backyard Chickens

Top 10 Birds for Raising Backyard Chickens (According to Chickenreview.com) When you’re picking your first flock, there are a few key things to look for: 1. The breed should be a recognized breed, and should be easy to find in most hatcheries. 2. The breed should have a reputation for docility, friendliness, and general tameness. 3. The breed should be fairly low-maintenance without too many care issues. You should decide whether you’re raising chickens for table meat or just eggs. If you want eggs, choose a breed that excels at laying. If you want meat, make sure to pick birds that gain weight quickly. The great thing about chickens is there are a few breeds that meet these criteria, making them excellent birds for the average backyard flock. Some of these birds are good layers and some are good layers and meat birds also! We’ve put together a list of our ten favorite chicken breeds for Urban or backyard flocks. Each of the breeds on our list meets most of the items to look for we’ve mentioned, and are very good birds for a beginner. 1: Rhode Island Red: The Best Dual-Purpose Bird: Easy to care for and a good layer! They are a popular choice for backyard flocks because of their egg laying abilities and hardiness. Although they can sometimes be stubborn, healthy hens can lay up to 5–6 eggs per week depending on their care and treatment. Rhode Island Red hens lay many more eggs than an average hen if provided plenty of quality feed 2: Buff Orpington: The Best Pet Chicken: The one caution on this breed is that their docile nature will often make them a target for bullying from other birds. -

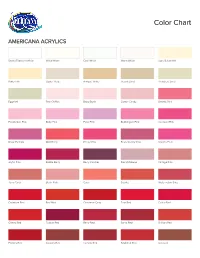

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

The Base Colors: Black and Chestnut the Tail, Called “Foal Fringes.”The Lower Legs Can Be So Pale That It Is Let’S Begin with the Base Colors

Foal Color 4.08 3/20/08 2:18 PM Page 44 he safe arrival of a newborn foal is cause for celebration. months the sun bleaches the foal’s birth coat, altering its appear- After checking to make sure all is well with the mare and ance even more. Other environmental issues, such as type and her new addition, the questions start to fly. What gender quality of feed, also can have a profound effect on color. And as we is it? Which traits did the foal get from each parent? And shall see, some colors do change drastically in appearance with Twhat color is it, anyway? Many times this question is not easily age, such as gray and the roany type of sabino. Finally, when the answered unless the breeder has seen many foals, of many colors, foal shed occurs, the new color coming in often looks dramatical- throughout many foaling seasons. In the landmark 1939 movie, ly dark. Is it any wonder that so many foals are registered an incor- “The Wizard of Oz,” MGM used gelatin to dye the “Horse of a rect—and sometimes genetically impossible—color each year? Different Color,” but Mother Nature does a darn good job of cre- So how do you identify your foal’s color? First, let’s keep some ating the same spectacular special effects on her foals! basic rules of genetics in mind. Two chestnuts will only produce The foal’s color from birth to the foal shed (which generally chestnut; horses of the cream, dun, and silver dilutions must have occurs between three and four months of age) can change due to had at least one parent with that particular dilution themselves; many factors, prompting some breeders to describe their foal as and grays must always have one gray parent. -

1 President's Message

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by David M. Cvet Summer is upon us with a vengeance, breaking temperature records from the 1930's – at least in Toronto. The warmer weather has had some fits and starts, with warm weather followed by frost, causing newly planted peppers and tomatoes to be damaged beyond saving. However, these exciting events pale in comparison to seeing the Queen's Beasts (some depicted on the right) who will be attending the Society's formal dinner at this year's Annual General Meeting, scheduled for October 1-3, 2010 in Ottawa. The Annual Meeting itself will be held at the Delta Ottawa Hotel on Queen Street. The Saturday evening dinner will take place at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (across the Ottawa River in Gatineau, Quebec), which will provide a grand setting for our annual banquet, graced as it will be with these impressive “guests”. We are indeed grateful to David Rumball for organizing this event, and for arranging with the museum to have the Queen's Beasts available for the dinner. I encourage our members to make the necessary calendar and travel to enhance the “coolness” factor of the Society in order to attract arrangements to attend this splendid event. new members – and to retain our present ones. One important reason for having the AGM in Ottawa this year As an example, at the recent Toronto Branch AGM (combined (rather than being hosted by the Prairie Branch, as it would have with the Society's Board meeting earlier the same day) the been in the usual sequence) is the expectation that the new formal dinner at Hart House was visually recorded by a Canadian Heraldic Authority tabard (donated by the Society) photographer I had arranged as my guest. -

128 AÜTO-HERALD a Program for the Construction of Heraldic

- 128 AÜTO-HERALD A Program for the Construction of Heraldic Drawings By C.B.Bayliss M.Sc University of Birmingham Centre for Computing and Computer Science Abstract In this paper I shall describe the main features of a program which constructs heraldic drawings. A description of a coat of arms is entered by a user in conventional heraldic terminology. The coat of arms is then constructed from a library of stored objects and fields and drawn on a terminal. Facilities exist for updating the library, and a picture editor is provided to allow a user to define new objects and fields. Contents Introduction Describing a coat of arms Method of coat of arms construction . Picture editor Library Device dependence and program structure. Conclusion Illustrations Fig I - Diagrams showing method of coat of arms constr- uction Fig 2 - Overall structure of the program - 129 Introduction In heraldry there are many different coats of arms which use a variety of objects in different combinations and colours. A coat of arms consists of a field ( the background ), which can be a colour, metal, fur or pattern which may have one or more objects placed upon it. Such objects are refered to as "charges" in heraldic terminology. A field may be divided, for example by quartering it or halving it. Each part of the field may be a different colour or pattern. Coats of arms are normally displayed on a shield. Colouring used on a coat of arras is called a tincture. There are five commonly used colours:- vert (green) azure (blue), gules (red), sable (black) and purpure (purple). -

Basic Horse Genetics

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Basic Horse Genetics ANR-1420 nderstanding the basic principles of genetics and Ugene-selection methods is essential for people in the horse-breeding business and is also beneficial to any horse owner when it comes to making decisions about a horse purchase, suitability, and utilization. Before getting into the basics of horse-breeding deci- sions, however, it is important that breeders under- stand the following terms. Chromosome - a rod-like body found in the cell nucleus that contains the genes. Chromosomes occur in pairs in all cells, with the exception of the sex cells (sperm and egg). Horses have 32 pairs of chromo- somes, and donkeys have 31 pairs. Gene - a small segment of chromosome (DNA) that contains the genetic code. Genes occur in pairs, one Quantitative traits - traits that show a continuous on each chromosome of a pair. range of phenotypic variation. Quantitative traits Alleles - the alternative states of a particular gene. The usually are controlled by more than one gene pair gene located at a fixed position on a chromosome will and are heavily influenced by environmental factors, contain a particular gene or one of its alleles. Multiple such as track condition, trainer expertise, and nutrition. alleles are possible. Because of these conditions, quantitative traits cannot be classified into distinct categories. Often, the impor- Genotype - the genetic makeup of an individual. With tant economic traits of livestock are quantitative—for alleles A and a, three possible genotypes are AA, Aa, example, cannon circumference and racing speed. and aa. Not all of these pairs of alleles will result in the same phenotype because pairs may have different Heritability - the portion of the total phenotypic modes of action. -

Color Coat Genetics

Color CAMERoatICAN ≤UARTER Genet HORSE ics Sorrel Chestnut Bay Brown Black Palomino Buckskin Cremello Perlino Red Dun Dun Grullo Red Roan Bay Roan Blue Roan Gray SORREL WHAT ARE THE COLOR GENETICS OF A SORREL? Like CHESTNUT, a SORREL carries TWO copies of the RED gene only (or rather, non-BLACK) meaning it allows for the color RED only. SORREL possesses no other color genes, including BLACK, regardless of parentage. It is completely recessive to all other coat colors. When breeding with a SORREL, any color other than SORREL will come exclusively from the other parent. A SORREL or CHESTNUT bred to a SORREL or CHESTNUT will yield SORREL or CHESTNUT 100 percent of the time. SORREL and CHESTNUT are the most common colors in American Quarter Horses. WHAT DOES A SORREL LOOK LIKE? The most common appearance of SORREL is a red body with a red mane and tail with no black points. But the SORREL can have variations of both body color and mane and tail color, both areas having a base of red. The mature body may be a bright red, deep red, or a darker red appearing almost as CHESTNUT, and any variation in between. The mane and tail are usually the same color as the body but may be blonde or flaxen. In fact, a light SORREL with a blonde or flaxen mane and tail may closely resemble (and is often confused with) a PALOMINO, and if a dorsal stripe is present (which a SORREL may have), it may be confused with a RED DUN.