The Bellary District Archaeological Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Krishna Temple Complex, Hampi: an Exploration of Its Identity As a Medieval Temple in the Contemporary Context

THE KRISHNA TEMPLE COMPLEX, HAMPI: AN EXPLORATION OF ITS IDENTITY AS A MEDIEVAL TEMPLE IN THE CONTEMPORARY CONTEXT A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Ashima Krishna January, 2009 © 2009 Ashima Krishna ABSTRACT Hindu temples in India have been in abundance for centuries. However, many have lost their use over time. They lie vacant and unused on vast tracts of land across the Indian subcontinent, in a time when financial resources for the provision of amenities to serve the local community are hard to come by. In the case of Hampi, this strain is felt not only by the community inhabiting the area, but the tourism sector as well. Hampi’s immense significance as a unique Medieval-city in the Indian subcontinent has increased tourist influx into the region, and added pressure on authorities to provide for amenities and facilities that can sustain the tourism industry. The site comprises near-intact Medieval structures, ruins in stone and archaeologically sensitive open land, making provision of tourist facilities extremely difficult. This raises the possibility of reusing one of the abundant temple structures to cater to some of these needs, akin to the Virupaksha Temple Complex and the Hampi Bazaar. But can it be done? There is a significant absence of research on possibilities of reusing a Hindu Temple. A major reason for this gap in scholarship has been due to the nature of the religion of Hinduism and its adherents. Communal and political forces over time have consistently viewed all Hindu temples as cultural patrimony of the people, despite legal ownership resting with the Government of India. -

Karnataka and Mysore

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY October 22, 1955 Views on States Reorganisation - / Karnataka and Mysore K N Subrahmanya THE recommendation of the States 4 the South Kanara district except will show vision and broadminded- Reorganisation Commission to Kasaragod taluk; ness in dealing with the Kannada form a Karnataka State bring 5 the Kollegal taluk of the Coim- population of the area in question ing together predominantly Kan batore district of Madras; and will provide for adequate educa nada-speaking areas presently scat 6 Coorg. tional facilities for them and also tered over five States has been ensure that they are not discriminat generally welcomed by a large sec The State thus formed will have ed against in the matter of recruit tion of Kannadigas who had a a population of 19 million and an ment to services." How far this genuine, long-standing complaint area of 72,730 square miles. paternal advice will be heeded re that their economic and cultural pro Criticism of the recommendations of mains to be seen. In this connection, gress was hampered owing to their the Commission, so far as it relates one fails to appreciate the attempt of numerical inferiority in the States to Karnataka State, falls into two the Commission to link up the Kolar dominated by other linguistic groups. categories. Firstly, there are those question with that of Bellary. In There is a feeling of satisfaction who welcome the suggestion to form treating Kolar as a bargaining coun among the Kannadigas over the a Karnataka State but complain that ter, the Commission has thrown to Commission's approach to the ques the Commission has excluded certain winds the principles that they had tion of the formation of a Karoatal.a areas, which on a purely linguistic set before them. -

A Study of Buddhist Sites in Karnataka

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicjournal.in Volume 3; Issue 6; November 2018; Page No. 215-218 A study of Buddhist sites in Karnataka Dr. B Suresha Associate Professor, Department of History, Govt. Arts College (Autonomous), Chitradurga, Karnataka, India Abstract Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha wandered the country side teaching what he had learned. He organized a community of monks known as the ‘Sangha’ to continue his teachings ofter his death. They preached the world, known as the Dharma. Keywords: Buddhism, meditation, Aihole, Badami, Banavasi, Brahmagiri, Chandravalli, dermal, Haigunda, Hampi, kanaginahally, Rajaghatta, Sannati, Karnataka Introduction of Ashoka, mauryanemperor (273 to 232 B.C.) it gained royal Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the support and began to spread more widely reaching Karnataka history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was and most of the Indian subcontinent also. Ashokan edicts founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of which are discovered in Karnataka delineating the basic tents Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got of Buddhism constitute the first written evidence about the enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha presence of the Buddhism in Karnataka. -

Bidar District “Disaster Management Plan 2015-16” ©Ãzàgà F¯Áè

BIDAR DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2015-16 Government of Karnataka Bidar District “Disaster Management Plan 2015-16” ©ÃzÀgÀ f¯Áè “““«¥ÀvÀÄÛ“«¥ÀvÀÄÛ ¤ªÀðºÀuÁ AiÉÆÃd£É 20152015----16161616”””” fĒÁè¢üPÁjUÀ¼À PÁAiÀiÁð®AiÀÄ ©ÃzÀgÀ fĒÉè BIDAR DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OFFICE, BIDAR. BIDAR DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2015-16 CONTENTS SL NO TOPIC PAGE NO 1 Preface 03 2 Glossary 04 3 Chapter-1 :Introduction 05-13 4 Chapter-2 : Bidar District Profile 14-25 5 Chapter-3 : Hazard Risk Vulnerability and Capacity (HRVC) 26-41 Analyses 6 Chapter-4 : Institution Mechanism 42-57 7 Chapter-5: Mitigation Plan 58-73 8 Chapter-6: Response Plan 74-80 9 Chapter-7: Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 81-96 10 Chapter-8 : Resources and Contact Numbers 97-117 11 Chapter-9 : Standard Operating Processor (SOPs) 118-125 12 Chapter-10 : Maps 126-137 13 Conclusion 138 14 Bibliography 139 BIDAR DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OFFICE, BIDAR. Bidar District Disaster Management Pla n 2015-16 Office of the Deputy Commissioner Bidar District, Bidar Shri. Anurag Tewari I. A.S Chairman of Disaster Management & Deputy Commissioner Phone: 08482-225409 (O), 225262(Fax) Bidar District E-mail: [email protected] PREFACE “Disaster” means unforeseen and serious threat to public life with suddenness in terms of time. Declaration of disaster depends on gravity or magnitude of situ ation, number of victims involved, time factor i.e. suddenness of an event, non- availability of medical care in terms of space, equipment’s medical and pa ramedical staff, medicines and other basic human needs like food, shelter and clothing, weather conditions in the locali ty of incident etc., thus enhancing human sufferings and create human needs that the victim cann ot alleviate without assistance. -

PROFILE of ANANTAPUR DISTRICT the Effective Functioning of Any Institution Largely Depends on The

PROFILE OF ANANTAPUR DISTRICT The effective functioning of any institution largely depends on the socio-economic environment in which it is functioning. It is especially true in case of institutions which are functioning for the development of rural areas. Hence, an attempt is made here to present a socio economic profile of Anantapur district, which happens to be one of the areas of operation of DRDA under study. Profile of Anantapur District Anantapur offers some vivid glimpses of the pre-historic past. It is generally held that the place got its name from 'Anantasagaram', a big tank, which means ‘Endless Ocean’. The villages of Anantasagaram and Bukkarayasamudram were constructed by Chilkkavodeya, the Minister of Bukka-I, a Vijayanagar ruler. Some authorities assert that Anantasagaram was named after Bukka's queen, while some contend that it must have been known after Anantarasa Chikkavodeya himself, as Bukka had no queen by that name. Anantapur is familiarly known as ‘Hande Anantapuram’. 'Hande' means chief of the Vijayanagar period. Anantapur and a few other places were gifted by the Vijayanagar rulers to Hanumappa Naidu of the Hande family. The place subsequently came under the Qutub Shahis, Mughals, and the Nawabs of Kadapa, although the Hande chiefs continued to rule as their subordinates. It was occupied by the Palegar of Bellary during the time of Ramappa but was eventually won back by 136 his son, Siddappa. Morari Rao Ghorpade attacked Anantapur in 1757. Though the army resisted for some time, Siddappa ultimately bought off the enemy for Rs.50, 000. Anantapur then came into the possession of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. -

GOGINENI VENKATA KRISHNA RAU, IAS Address: Date of Birth: 30 July 1954

ICC 106‐14 16 March 2011 Original: English E International Coffee Council Nomination for the post of 106th Session Executive Director 28 – 31 March 2011 London, United Kingdom Submitted by India Background 1. In accordance with the procedures for the appointment of a permanent Executive Director which were approved by the Council at its 105th Session from 21 to 24 September 2010 (see document ICC‐105‐22), the Government of India has submitted the attached proposal for the appointment to the position of Executive Director of Mr G.V. Krishna Rau, including the curriculum vitae of the candidate. 2. The procedures provide that the Council shall review the list of candidates whose names were submitted by the deadline of 15 March 2011 and, if necessary, may decide to establish a Screening Committee. The Screening Committee shall review the list of candidates and recommend to the Council no more than five candidates to be invited to the September 2011 Council Session in order to make presentations on their candidacy. If the establishment of the Screening Committee is necessary, its report and recommendation shall be distributed to Members no later than 30 June 2011. Members who wish to comment on the recommendations of the Screening Committee shall provide those comments in writing no later than 31 July 2011. Following the presentations by candidates to the Council Session in September 2011, the Council shall consider and decide on the appointment of the Executive Director. Action The Council is requested to consider this document. G V Krishna -

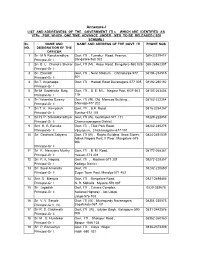

Annexure-I LIST and ADDRESSESS of the GOVERNMENT ITI S WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS Vtps for WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES to BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL

Annexure-I LIST AND ADDRESSESS OF THE GOVERNMENT ITI s WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS VTPs FOR WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES TO BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL. NAME AND NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE GOVT. ITI PHONE NOS NO. DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICER 1 Sri M N Renukaradhya Govt. ITI , Tumakur Road, Peenya, 080-23379417 Principal-Gr I Bangalore-560 022 2 Sri B. L. Chandra Shekar Govt. ITI (M) , Hosur Road, Bangalore-560 029 080-26562307 Principal-Gr I 3 Sri Ekanath Govt. ITI , Near Stadium , Chitradurga-577 08194-234515 Principal-Gr II 501 4 Sri T. Anjanappa Govt. ITI , Hadadi Road Davanagere-577 005 08192-260192 Principal-Gr I 5 Sri M Sadathulla Baig Govt. ITI , B. E. M.L. Nagara Post, KGF-563 08153-263404 Principal-Gr I 115 6 Sri Yekantha Swamy Govt. ITI (W), Old Momcos Building, , 08182-222254 Principal-Gr II Shimoga-577 202 7 Sri T. K. Kempaiah Govt. ITI , B.H. Road, 0816-2254257 Principal-Gr II Tumkur-572 101 8 Sri H. P. Srikanataradhya Govt. ITI (W), Gundlupet-571 111 08229-222853 Principal-Gr II Chamarajanagara District 9 Smt K. R. Renuka Govt. ITI , Tilak Park Road, 08262-235275 Principal-Gr II Vijayapura, Chickamagalur-577 101 10 Sri Giridhara Saliyana Govt. ITI (W) , Raghu Building Urwa Stores, 0824-2451539 Ashok Nagara Post, II Floor, Mangalore-575 006. Principal-Gr II 11 Sri K. Narayana Murthy Govt. ITI , B. M. Road, 08172-268361 Principal-Gr II Hassan-573 201 12 Sri P. K. Nagaraj Govt. ITI , Madikeri-571 201 08272-228357 Principal-Gr I Kodagu District 13 Sri Syed Amanulla Govt. -

Ethnomedicinal Plants Used by Rajgond Tribes of Haladkeri Village in Bidar District, Karnataka, India

Innovare International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Academic Sciences ISSN- 0975-1491 Vol 7, Issue 8, 2015 Original Article ETHNOMEDICINAL PLANTS USED BY RAJGOND TRIBES OF HALADKERI VILLAGE IN BIDAR DISTRICT, KARNATAKA, INDIA SURYAWANSHI POOJA1, VIDYASAGAR G M1* 1*Medicinal Plants and Microbiology Research Laboratory, Department of Post-Graduate, Studies and Research in Botany, Gulbarga University, Kalaburagi 585106, Karnataka, India Email: [email protected] Received: 07 Jan 2015 Revised and Accepted: 20 Jun 2015 ABSTRACT Objective: Present work deals with the studies on Ethnomedicinal plants used by Rajgond Tribes of Haladkeri village in Bidar District, Karnataka, India Methods: Field trips were conducted from March to December, 2014 to collect the information on the medicinal plants used in the treatment of different ailments by Rajgond Tribe using the methodology suggested by Jain and Goel. Results: A total of 12 Vaidyas or healers were interviewed and 60 ethno medicinal plants species belonging to 37 families were recorded along with their scientific names, vernacular names, botanical family, parts used and their ethno medicinal significance. Conclusion: Rajgond Tribe of Haladkeri Village in Bidar District is far away from modern medicine even in 21st Century and is known for their unique way of life and disease management. As the majority of people in modern days is much conscious about their health and aware of the side effects of modern drugs, such study of ethnic drugs may turn a useful base in finding out new drug molecules. Keywords: Ethno medicinal plants, Rajgond, Tribe, Haladkeri, Bidar District. INTRODUCTION Panchayath in Bidar District of Karnataka State, India. -

State: KARNATAKA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: BIJAPUR

State: KARNATAKA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: BIJAPUR 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro -Climatic/Ecological Zone Agro Ecological Sub Region Deccan Plateau, hot semi arid ecosub region ( 6.1 ) (ICAR) Agro-Climatic Region (Planning Southern Plateau and Hill Region (X) Commission) Agro Climatic Zone (NARP) Northern Dry Zone (KA-3) List all the districts or part thereof Entire District: Bijapur, Bagalkot, Gadag, Bellary, Koppal falling under the NARP Zone Part of District: Belgaum, Dharwad, Raichur, Davanagere Geographic coordinates of district Latitude Longitude Altitude 16º 49'N 75º 43'E 593 .0 m Name and address of the Regional Agricultural R esearch Station, P. B.No. 18 concerned ZRS/ ZARS/ RARS/ BIJAPUR - 586 101 RRS/ RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Bijapur 1.2 Rainfall Average (mm) Normal Onset Normal Cessation SW monsoon (June-Sep): 387.5 2 nd week of June NE Monsoon (Oct -Dec): 130 .0 4 th week of October to 4 th week of November Winter (Jan- Feb) 6.8 - - Summer (Mar-May) 56.1 - - Annual 594.4 - - 1.3 Land use Geographical Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other pattern of area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows the agricultural Misc. tree Land district use crops and groves Area 1053.5 2.0 35.8 9.6 5.5 1.3 29.1 85.3 5.7 (‘000 ha) 1. 4 Major Soils Area (‘000 ha) Percent (%) of total Medium black soils 401.3 40 Shallow black soils 262.5 26 Deep black soils 234.2 23 Red loamy soils 48.1 5 Red sandy soils 20.2 2 Red and -

Stone Axe Technology in Neolithic South India: New Evidence from the Sanganakallu-Kupgal Region) Mideastern Karnataka

Stone Axe Technology in Neolithic South India: New Evidence from the Sanganakallu-Kupgal Region) Mideastern Karnataka ADAM BRUMM, NICOLE BOIVIN, RAVI KORISETTAR, JINU KOSHY, AND PAULA WHITTAKER THE TRANSITION TO AGRICULTURE-and to settled village life-occurred at dif ferent times in various parts of the world. Even within the Indian subcontinent, the Neolithic transition did not occur simultaneously across the entire region; rather, Neolithic "pockets" developed at different moments in certain key areas within the subcontinent. One such area is the South Deccan Plateau in South India, where the third millennium B.C. saw the development ofa novel Neolithic way of life that differed in crucial ways from Neolithic lifeways in other parts of the subcontinent (Allchin 1963). This tradition was marked by a particular focus on cattle and by the appearance of specific, perhaps ritual practices that featured the burning of large quantities of cow dung and the resultant creation of ash mounds in the landscape (Allchin 1963; Boivin 2004). This unique Neolithic tra dition, while still relatively poorly understood compared to Neolithic cultures in Europe and the Near East, has much to offer prehistorians attempting to under stand the changes that led to and accompanied domestication and sedentarization. It also has much to offer South Asian scholars who wish to gain a better apprecia tion of the changes that led to complexity, political economy, and state-level societies in South India (Boivin et al. 2005; Fuller et al. forthcoming). One key requirement for such studies is a better understanding of the material culture changes that attended the Neolithic transition, as well as the subsequent transition from the Neolithic to the Megalithic or Iron Age (see Table 1 for period designa tions and chronology). -

Origins & Spread of Agriculture in India. Dorian Q Fuller 2008.4.18

Origins & Spread of Agriculture in India. Dorian Q Fuller 2008.4.18 印度的农业起源和传播 Figure 1. The major independent Neolithic zones of South Asia, with selected archaeological sites. For each zones the solid grey outline indicates best guess region(s) for indigenous domestication processes and/or earliest adoption of agriculture. The dashed lines indicates the expanded region of related/derivative traditions of agriculture; selected sites plotted. 图一,南亚各新石器区分布,含主要遗址位置。实线范围为本地驯化的最可能区域或 最早接受农业的区域;虚线为这一传统的传播扩大区域 1. The northwestern zone, with the disjunct area of the Northern Neolithic shown: Mgr. Mehrgarh, Glg. Ghaleghay, Bzm. Burzahom, Gfk. Gufkral. 2. The middle Ganges zone with two possible rice domestication areas: Dmd. Damadama, Lhd. Lahuradewa, Mhg. Mahagara, Kjn. Kunjhun, Snr. Senuwar. 3. Eastern India/Orissan zone: Bnb. Banabasa, Kch. Kuchai, Gpr, Gopalpur, Gbsn. Golabai Sassan. 4. Gujarat and southern Aravalli zone: Ltw. Loteshwar, Rjd. Rojdi, Pdr. Padri, Btl. Balathal, Bgr. Bagor. 5. Southern Indian zone: Bdl. Budihal, Wtg. Watgal, Utr. Utnur, Sgk. Sanganakallu and Hiregudda, Hlr. Hallur, Ngr. Nagarajupalle. 1 Chronological Framework (based on Fuller 2006 Journal of World Prehistory 20: 1-86)印度 新石器-铜石并用时代编年 2 Table 1. Important domesticates in South Asia originating in the Near East 表一,近东起源传入南亚的驯化物种 Species Region and period of Earliest occurrence in Comments 备注 origin South Asia 最早出现 于南亚的地区年代 Wheat(s) Near Eastern fertile Mehrgarh, ca. 7000 BC Mehrgarh finds include Triticum spp.小麦 crescent, 9700-8000 primitive glume wheats BC (Triticum monococcum, T. diococcum) as well as derived free- threshing breadwheats (T. aestivum) Barley 大麦 Near Eastern fertile Mehrgarh, ca. 7000 BC Wild barley also Hordeum vulgare crescent, 9700-8000 reported at Mehrgarh, BC. -

Address of Canara Bank Wings Identified for Concurrent/ Continuous Audit by External Chartered Accountants for the Period 01St July 2021 to 30Th June 2022

ADDRESS OF CANARA BANK WINGS IDENTIFIED FOR CONCURRENT/ CONTINUOUS AUDIT BY EXTERNAL CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS FOR THE PERIOD 01ST JULY 2021 TO 30TH JUNE 2022 S no DP Branch Name Circle Address City Pin code State Dist. 1. 6987 CPC - FT Manipal Integrated Treasury Wing, Manipal 576104 Karnataka Udupi HO Annex, II Floor, 2. 6805 CPC –FT Mumbai Canara Bank Bldgs, 8th Mumbai 400051 Maharashtra Mumbai Suburban Floor, C-14, G-Block, MCA Club, Bandra-Kurla Complex, ADDRESS OF CANARA BANK LARGE CORPORATE BRANCHES IDENTIFIED FOR CONCURRENT/ CONTINUOUS AUDIT BY EXTERNAL CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS FOR THE PERIOD 01ST JULY 2021 TO 30TH JUNE 2022 S no DP Branch Name Circle Address City Pin code State Dist. 3. 4891 CHANDIGARH LARGE Chandigarh SCO 117-119, Sector-17C, Chandigarh 160017 Chandigarh-UT Chandigarh CORPORATE BRANCH Chandigarh 4. 2636 BENGALURU LARGE Bengaluru #18, Ramanashree Arcade, Bengaluru 560001 Karnataka Bengaluru Urban CORPORATE BRANCH III Floor, M G Road, 5. 1942 NEW DELHI Delhi II Floor, 9, World Trade Delhi 110002 NCT of Delhi-UT New Delhi CONNAUGHT PLACE Tower, Barakambha Lane, LARGE CORPORATE BRANCH 6. 19531 LARGE CORPORATE Kolkata ILLACO HOUSE, 1, Kolkata 700001 West Bengal Kolkata BRANCH KOLKATA BRABOURNE ROAD, BRABOURNE ROAD LARGE CORPORATE BRANCH, Page 1 of 45 ADDRESS OF CANARA BANK RETAIL ASSET HUBs IDENTIFIED FOR CONCURRENT/ CONTINUOUS AUDIT BY EXTERNAL CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS FOR THE PERIOD 01ST JULY 2021 TO 30TH JUNE 2022 S no DP Branch Name Circle Address City Pin code State Dist. 7. 2284 RAH ANANTHAPUR Vijayawada Near Clock Tower, I Floor, Anantapur 515001 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur Canara Bank Branch Main-II, 8.