Critiquing Exhibits: Meanings and Realities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Biography [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7532/biography-pdf-547532.webp)

Biography [PDF]

NICELLE BEAUCHENE GALLERY RICHARD BOSMAN (b. 1944, Madras, India) Lives and works in Esopus, New York EDUCATION 1971 The New York Studio School, New York, NY 1970 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME 1969 The Byam Shaw School of Painting and Drawing, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 High Anxiety, Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York, NY 2018 Doors, Freddy Gallery, Harris, NY Crazy Cats, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY 2015 The Antipodes, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne, Australia Raw Cuts, Cross Contemporary Art, Saugerties, NY 2014 Death and The Sea, Owen James Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Paintings of Modern Life, Carroll and Sons, Boston, MA Some Stories, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Art History: Fact and Fiction, Carroll and Sons, Boston, MA 2011 Art History: Fact and Fiction, Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock, NY 2007 Rough Terrain, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY 2005 New Paintings, Bernard Toale Gallery, Boston, MA 2004 Richard Bosman, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY Richard Bosman, Mark Moore Gallery, Santa Monica, CA 2003 Richard Bosman, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY Just Below the Surface: Current and Early Relief Prints, Solo Impression Inc, New York, NY 1996 Prints by Richard Bosman From the Collection of Wilson Nolen, The Century Association, New York, NY Close to the Surface - The Expressionist Prints of Eduard Munch and Richard Bosman, The Columbus Museum, Columbus, GA 1995 Prints by Richard Bosman, Quartet Editions, Chicago, IL 1994 Richard Bosman: Fragments, -

New Museum Newsletter Spring/Summer 1984

BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE NEW MUSEUM John Neely Henry Luce Ill STAFF Youth Program Instructor/ President Kimball Augustus Gallery SupeNisor Vera G. Ust Chief of Security Eileen Pryor McGann Vice President Eric Bemlsderfer Manager, Catalog Arthur A. Goldberg Assistant Preparator Subscription and Distribution Treasurer Gayle Brandel Usa Parr Acting Administrator Curatorial Assistant Jack Boulton Mary Clancy Ned Rifkin Gregory C. Clark Administrative Ass1stant Curator Elaine Dannhelsser Pamela Freund Jessica Schwartz Public Relations/Special Director of Public Relations Richard Ekstract Events Assistant and Special Events John Fitting, Jr. Lynn Gumpert Charles A. Schwefel Allen Goldring Curator Director of Planning and Eugene P. Gorman John K. Jacobs Development Reg1strar! Preparator Paul C. Harper, Jr. Maureen Stewart Ed Jones Bookkeeper Martin E. Kantor Director of Education Marcia Tucker Nanette L Laltman Elon Joseph Director Mary McFadden Guard Lorry Wall Denis O'Brien Maureen Mullen Admissions/Bookstore Admissions/ Bookstore Assistant Patrick Savin Assistant Brian Wallis Herman Schwartzman Marcia Landsman Editorial Consultant Laura Skoler Curatorial Coordinator Janis Weinberger Marcia Tucker Susan Napack Reception Admissions/Bookstore TlmYohn Coordinator Editor The New Museum at 583 Broadway in SoHo. TheNewMuseum OF CONTEMPORARY ART S P R NG/SUMMER 1 9 8 4 photo· 01rk Rowntree FRONTLINES PRESIDENT'S REPORT photo Beverly Owen It is certainly not every season that a museum director 's creative muse takes the form of giving birth to a real Edited by: Saddler, Charles A. (above) Beverly baby. So it was a very special milestone when , on Jessica Schwartz Schwefel, Frank Owen's Toon, the January 3, Ruby Dora McNeil was born to Director Assistant Editor: Stewart, John Waite, spring window Marcia Tucker and husband Dean McNeil. -

Mark Tansey Reverb

G A G O S I A N February 8, 2017 MARK TANSEY REVERB Opening reception: Wednesday, February 8, 6–8PM February 8–March 25, 2017 Park & 75 821 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 Picture a deck of cards based on eye-mind-hand contradictions. To play the game, select some cards, shuffle them, and continue by finding new analogies. You make up the cards as you go. You perform the contradictions in order to realize or understand them. Sometimes new features or behaviors emerge. Sometimes it might seem as though the deck is infinite. —Mark Tansey Gagosian is pleased to present “Reverb,” an exhibition of two works by Mark Tansey: a new oil painting Reverb (2017) and Wheel (1990), a wooden sculpture. Page 1 of 3 G A G O S I A N Each of Tansey's paintings is a visual and metaphorical adventure in the nature and implications of perception, meaning, and interpretation in art. Working with the conventions and structures of figurative painting, he creates visual corollaries for sometimes arcane literary, philosophical, historical, and mathematical concepts. His exhaustive knowledge of art history accumulates in paintings through a time-intensive process. Images are mined from a vast trove of primary and secondary sources assembled over decades—magazine, journal and newspaper clippings, as well as his own photographs—which he submits to an intensive process of manipulation. The strictly duotone paintings have a precise photographic quality reminiscent of scientific illustration, achieved by applying gesso then washing, brushing and scraping paint into it. Through absurdist composition and intricate detail, in Reverb Tansey draws unlikely associations between different modes of representation. -

RE-FRAMING the AMERICAN WEST: CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ENGAGE HISTORY by © 2015 Mindy N. Besaw Submitted to the Graduate Degree Pr

RE-FRAMING THE AMERICAN WEST: CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ENGAGE HISTORY By © 2015 Mindy N. Besaw Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Kress Foundation Department of Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ Co-chairperson, Charles C. Eldredge _______________________________ Co-chairperson, David C. Cateforis _______________________________ John Pultz ______________________________ Stephen Goddard ______________________________ Michael J. Krueger Date Defended: November 30, 2015 The Dissertation Committee for MINDY N. BESAW certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RE-FRAMING THE AMERICAN WEST: CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ENGAGE HISTORY _______________________________ Co-chairperson, Charles C. Eldredge _______________________________ Co-chairperson, David C. Cateforis Date approved: November 30, 2015 ii Abstract This study examines contemporary artists who revisit, revise, reimagine, reclaim, and otherwise engage directly with art of the American Frontier from 1820-1920. The revision of the historic images calls attention to the myth and ideologies imbedded in the imagery. Likewise, these contemporary images are essentially a framing of western imagery informed by a system of values and interpretive strategies of the present. The re-framing of the historic West opens a dialogue that expands beyond the frame, to look at images and history from different angles. This dissertation examines twentieth- and twenty-first century artists such as the Cowboy Artists of America, Mark Klett, Tony Foster, Byron Wolfe, Stephen Hannock, Bill Schenck, and Kent Monkman alongside historic western American artists such as Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, Timothy O’Sullivan, Thomas Moran, W.R. Leigh, and Albert Bierstadt. -

Narrative Painting the Art Museum at Florida International University Frost Art Museum the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Frost Art Museum Catalogs Frost Art Museum 5-6-1988 American Art Today: Narrative Painting The Art Museum at Florida International University Frost Art Museum The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/frostcatalogs Recommended Citation Frost Art Museum, The Art Museum at Florida International University, "American Art Today: Narrative Painting" (1988). Frost Art Museum Catalogs. 49. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/frostcatalogs/49 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Frost Art Museum at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Frost Art Museum Catalogs by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Art Today: Narrative Painting May 6 - June 4, 1988 Organized by Dahlia Morgan for The Art Museum at Florida International University The State University ofFlorida at Miami Exhibiting Artists Philip Ayers Robert Birmelin jim Butler David Carbone Beth Foley james Gingerich Leon Golub Mark Greenwold Luis jimenez Gabriel Laderman Alfred Leslie james McGarrell Raoul Middleman Daniel O'Sullivan jim Peters Mark Tansey jerome Witkin Lenders to the Exhibition Claude Bernard Gallery, New York, New York Eli Broad Family Foundation, Los Angeles, California CDS Gallery, New York, New York jessica Darraby Gallery, Los Angeles, California Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York Sherry French Gallery, New York, New York Frumkin/Adams Gallery, New York, New York Brian Hauptli and Norman Francis, San Francisco, California Kraushaar Galleries, New York, New York Emily Fisher Landau, New York, New York Adair Margo Gallery, El Paso, Texas Raoul Middleman, Baltimore, Maryland Prudential Insurance Company of America, Newark, New jersey A. -

Heroic Painting

HEROI F36 12:H55 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/heroicpaintingfeOOIubo EROIC PAINI ING FEBRUARY 3 - APRIL 21, 1996 SECCA SOUTHEASTERN CENTER FOR CONTEMPORARY ART Sara Lee Corporation is the corporate sponsorfor this exhibition ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A number of people helped me understand the Douglas Bohr, installations manager/registrar, and evolving notion of the hero that is explored in Karin Lusk, executive administrative assistant, "Heroic Painting." They work in diverse fields from coordinated the research and administration of the social services to the arts, but all in some way installation and catalogue. Their contribution far interface with the heroic acts of daily life. I am exceeded the parameters of their jobs. I would also grateful to Gayle Dorman, Suzi Gablik, Connie like to acknowledge Jeff Fleming, curator; AngeUa Grey, Nan Holbrook, Basil Talbott, and Emily Debnam, programs administrative assistant; and Wilson for their input. Mel White, programs assistant. Thanks are also due to Ruth Beesch, director of Finally, I am indebted to the artists for providing the Weatherspoon Art Gallery, for helping me in insights on their work and to the lenders for their my search for women artists. SECCA's staff worked generosity. diligently on many aspects of the exhibition. — S.L. This publication accompanies the exhibition EXHIBITION TOUR: "HEROIC PAINTING" Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida May 5 - June 30, 1996 February 3 - April 21, 1996 Queens Museum of Art, New York at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, July 19 - September 8, 1996 Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Knoxville Museum of Art, ICnoxville, Tennessee October 11, 1996 - January 12, 1997 SECCA is supported by The Arts Council of Winston-Salem and Forsyth County, and the The Contemporary Arts Center, North Carolina Arts Council, a state agency. -

Teaching Art Since 1950

Art since 1950 Teaching National Gallery of Art, Washington This publication is made possible by the PaineWebber Endowment Special thanks are owed to Arthur Danto for his generosity; Dorothy for the Teacher Institute. Support is also provided by the William and Herbert Vogel for kind permission to reproduce slides of Joseph Randolph Hearst Endowed Fund for the Teacher Institute. Kosuth’s Art as Idea: Nothing; Barbara Moore for help in concept Additional grants have been provided by the GE Fund, The Circle development; Linda Downs for support; Marla Prather, Jeffrey Weiss, of the National Gallery of Art, the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, and Molly Donovan of the Department of Twentieth-Century Art, and the Rhode Island Foundation. National Gallery of Art, for thoughtful suggestions and review; Sally Shelburne and Martha Richler, whose earlier texts form the basis of entries on Elizabeth Murray and Roy Lichtenstein, respectively; © 1999 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington Donna Mann, who contributed to the introduction; and Paige Simpson, who researched the timeline. Additional thanks for assis- tance in obtaining photographs go to Megan Howell, Lee Ewing, NOTE TO THE READER Ruth Fine, Leo Kasun, Carlotta Owens, Charles Ritchie, Laura Rivers, Meg Melvin, and the staff of Imaging and Visual Services, National This teaching packet is designed to help teachers, primarily in the Gallery of Art; Sam Gilliam; Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van upper grades, talk with their students about art produced since 1950 Bruggen; and Wendy Hurlock, Archives of American Art. and some of the issues it raises. The focus is on selected works from the collection of the National Gallery of Art. -

Contemporary Art Market Report

04 EDITORIAL BY THIERRY EHRMANN 05 INTRODUCTION 06 GROWTH 08 THE CONTEMPORARY ART RUSH 14 THE MARKET’S PILLARS 22 PAINTING... ABOVE ALL 26 DIVERSITY 28 A NEW LANDSCAPE 36 “NO MAN’S LAND” 40 BLACK (ALSO) MATTERS (IN ART) 42 VALUATION 44 IN SEARCH OF NOVELTY 48 MULTIPLE CHOICE... 52 DIGITAL AGILITY 55 TOP 1,000 Methodology The analysis of the Art Market presented in this report is based on results from Fine Art public auctions during the period from 1 January 2000 to 30 June 2020. This report covers exclusively paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, prints, videos and installations by contem- porary artists -herein defined as artists born after 1945, and excludes antiques, anonymous cultural goods and furniture. All the auction results indicated in this report include the buyer’s premium. Prices are indicated in US dollars ($). Millions are abbreviated to “m”, billions to “bn”. 3 EDITORIAL BY THIERRY EHRMANN Artprice is proud to present this exclusive report which Inspired by Pop Art, Contemporary Art continues to traces the evolution of the Contemporary Art Market democratize, to engage in dialogues with a much wider over 20 years. The story it tells reflects a multitude of audience. Street Art symbolizes this breadth of appeal: sociological, geopolitical and historical factors, all of Banksy’s stencils are known all over the world. Among which contributed to the rapid rise of Contemporary today’s youngest generations, the recognition of female Art in the global Art Market. A marginal segment until artists represents an even more important revolution, the end of the 1990s, Contemporary Art now accounts to which must be added the new success of artists from for 15% of global Fine Art auction turnover, and is now Africa and the African diaspora. -

Icons of Contemporary Painting at Christie’S London Post-War & Contemporary Art Evening Auction

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON | 3 OCTOBER 2013 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ICONS OF CONTEMPORARY PAINTING AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART EVENING AUCTION Glenn Brown, Böcklin’s Tomb (copied from ‘Floating Cities’ 1981 by Chris Foss), oil on canvas, painted in 1998, estimate: £2-3M London - Christie’s London Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Auction on 18 October 2013 will present a strong selection of contemporary painting with a focus on works created during the last 30 years. The auction will feature exceptional works by masters such as Martin Kippenberger, Glenn Brown and Mark Tansey, as well as Peter Doig, who has a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Scotland, and Brazilian artist Mira Schendel, the subject of a solo show at Tate Modern. Francis Outred, Christie's Head of Post-War & Contemporary Art, Europe: “Our October sale season is the most contemporary ever, focused on works from 1980 onwards, with a cutting-edge spirit to coincide with Frieze week in London. Highlights include an exceptional selection of icons of contemporary photography by artists including Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Jeff Wall and Gabriel Orozco. Another strength this season is contemporary painting by artists of different generations. We are offering works by established masters (Gerhard Richter, Martin Kippenberger, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol) and mid-career artists, including Glenn Brown, Mark Tansey and Christopher Wool, who has a retrospective at the Guggenheim New York, opening later this month. We are also proud to present younger artists, such as Oscar Murillo, who has a solo show on now at the South London Gallery, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, who has been shortlisted for the Turner Prize. -

Center 21 National Gallery of Art Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Center 21 Q

~ii? ~ Center 21 National Gallery of Art Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Center 21 Q D I I o o o i m • ' ! J.L!li I11i III - If- Ip II dl l I .-,,~ _ III / - / .;P" ........~ ,~.~-~ .._,,i -~m., --~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 21 Record of Activities and Research Reports June zooo-May zoox Washington ZOOI National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D. C. zo565 Telephone: (zoz) 84z-648o Facsimile: (zoz) 84z-6733 E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: www.nga.gov/resources/casva.htm All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. zo565 Copyright © zoo~ Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington This publication was produced by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts and the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington Printed by Schneidereith and Sons, Baltimore, Maryland Cover: Design Study for the East Building, I. M. Pei & Partners, National Gallery of Art East Building Design Team, October i968. Gallery Archives, National Gallery of Art Frontispiece: Study Center Interior, East Building, National Gallery of Art. Photograph by Rob Shelley Contents 6 Preface 7 Report on the Academic Year, June 2ooo-May zooi 8 Board of Advisors and Special Selection Committees 9 Staff z~ Report of the Dean z 5 Members z~ Meetings 34 Lecture Abstracts 37 Incontri Abstracts 4z Research Projects 44 Publications 45 Research Reports of Members ~75 Description of Programs I77 Fields of Inquiry I77 Fellowship Program ~85 Facilities i86 Board of Advisors and Special Selection Committees x86 Program of Meetings, Research, and Publications I9z Index of Members' Research Reports, zooo-zoox Preface The Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, a research insti- tute which fosters study of the production, use, and cultural mean- ing of art, artifacts, architecture, and urbanism, from prehistoric times to the present, was founded in i979 as part of the National Gallery of Art. -

Mark Tansey Biography

G A G O S I A N Mark Tansey Biography Born 1949, San Jose, CA. Lives and works in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and New York, NY. Education: 1975–78 Graduate Studies in Painting, Hunter College, New York, NY. 1972 B.A., Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles, CA. Solo Exhibitions: 2017 Mark Tansey: Reverb. Gagosian Gallery, Park & 75, New York, NY. 2011 Mark Tansey. Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. 2009 Mark Tansey. Gagosian Gallery, London, England. 2005 Mark Tansey. Fisher Landau Center for Art, Long Island City, NY. Mark Tansey. Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Germany. Traveled to: Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, Germany. 2004 Mark Tansey. Gagosian Gallery, W. 24th St., New York, NY. 2000 Mark Tansey: Graphs. Curt Marcus Gallery, New York, NY. 1997 Mark Tansey. Curt Marcus Gallery, New York, NY. 1995 Borders. Galleri Faurschou, Copenhagen, Denmark. Triumph of the New York School. Kunstverein, Düsseldorf, Germany. 1994 Landscape as Metaphor. Denver Art Museum, CO. Traveled to: Columbus Art Museum, OH. 1993 Mark Tansey. Kohn/Abrams Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Mark Tansey. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA. Traveled to: Milwaukee Museum of Art, WI; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Canada. Twenty-eight Pictures. Curt Marcus Gallery, New York, NY. 1992 Mark Tansey. Curt Marcus Gallery, New York, NY. 1990 Mark Tansey: Art and Source (curated by Patterson Sims). Seattle Art Museum, WA. Traveled to: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Canada; St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; List Visual Art Center, MIT, Cambridge, MA; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX. -

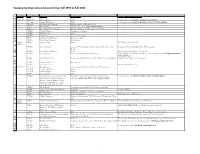

Tuesday Evening Lecture Series Archive: Fall 1991 to Fall 2014

Tuesday Evening Lecture Series Archive: Fall 1991 to Fall 2014 A B C D E 1 Season Date Speaker Credentials Lecture Title or Description 2 F all 1 991 1 0-S e p Mark Tansey Artis t In conjunction with Mark Tansey: Art and Source 3 1 7-S ep Antony Gormley Artis t In conjunction with Antony Gormley: Field and Other Figures 4 24-S ep Dr. R ichard R . Brettell Director, Dallas Mus eum of Art 5 1 -Oct David Dillon Architecture critic, Dallas Morning News 6 8-Oct Dr. Edmund P. Pillsbury Director, Kimbell Art Mus eum, F ort Worth 7 1 5-Oct John L. Marion Chairman, Sotheby's 8 22-Oct Chris Powell Artis t 9 29-Oct S ue Gra ze Freelance curator 10 5-Nov Holly and Jay Krueger Art cons ervators 11 1 2-Nov Mark Thistlethwaite Art his torian Spring 3-Mar J ames S urls Artis t "Art: T he S earch for S elf" 12 1 992 1 0-Ma r Tom Southall Curator of Photography, Amon Carter Mus eum, F ort "Paparazzi Pop: Andy Warhol's Photography" 13 Worth 14 24-Mar Celia Alvarez Muñoz Artis t "How Personal Aesthetic is Formed" 31 -Mar Joan Banach Curator, Robert Motherwell Estate "Robert Motherwell: A S tudio Memoir," in conjunction with Robert Motherwell: 15 The Open Door 7-Apr John Maruszczak Profes s or of Architecture, Univers ity of T exas , Arlington "Aquatic Set: Water in Landscape" 16 17 1 4-Apr Raymond Nasher Art collector 18 21 -Apr Panel discussion The Fort Worth School 19 F all 1 992 1 5-S ep Gary Garrels S enior Curator, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis 20 22-S ep Lee N.