(2011). AB Dobrowolski–The First Cryospheric Scientist–And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

The Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic Treaty Measures adopted at the Thirty-ninth Consultative Meeting held at Santiago, Chile 23 May – 1 June 2016 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty November 2017 Cm 9542 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Treaty Section, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, King Charles Street, London, SW1A 2AH ISBN 978-1-5286-0126-9 CCS1117441642 11/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majestyʼs Stationery Office MEASURES ADOPTED AT THE THIRTY-NINTH ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Santiago, Chile 23 May – 1 June 2016 The Measures1 adopted at the Thirty-ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting are reproduced below from the Final Report of the Meeting. In accordance with Article IX, paragraph 4, of the Antarctic Treaty, the Measures adopted at Consultative Meetings become effective upon approval by all Contracting Parties whose representatives were entitled to participate in the meeting at which they were adopted (i.e. all the Consultative Parties). The full text of the Final Report of the Meeting, including the Decisions and Resolutions adopted at that Meeting and colour copies of the maps found in this command paper, is available on the website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat at www.ats.aq/documents. -

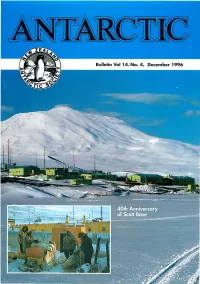

Antarctic.V14.4.1996.Pdf

Antarctic Contents Foreword by Sir Vivian Fuchs Forthcoming Events Cover Story Scott Base 40 Years Ago by Margaret Bradshaw... Cover: Main: How Scott Base looks International today. Three Attempt a World Record Photo — Courtesy of Antarctica New Zealand Library. Solo-Antarctic Crossing National Programmes New Zealand United States of America France Australia Insert: Scott Base during its South Africa final building stage 1957. Photo — Courtesy of Guy on Warren. Education December 1996, Tourism Volume 1 4, No. 4, Echoes of the Past Issue No.l 59 Memory Moments Relived. ANTARCTIC is published quar terly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc., ISSN Historical 01)03-5327, Riddles of the Antarctic Peninsula by D Yelverton. Editor: Shelley Grell Please address all editorial Tributes inquiries and contributions to the Editor, P O Box -104, Sir Robin Irvine Christchurch or Ian Harkess telephone 03 365 0344, facsimile 03 365 4255, e-mail Book Reviews [email protected]. DECEMBER 1996 Antargic Foreword By Sir Vivian Fuchs All the world's Antarcticians will wish to congratulate New Zealand on maintaining Scott Base for the last forty years, and for the valuable scientific work which has been accom plished. First established to receive the Crossing Party of the Commonwealth Trans- Antarctic Expedition 1955-58, it also housed the New Zealand P a r t y w o r k i n g f o r t h e International Geophysical Year. Today the original huts have been replaced by a more modern„. , j . , Sir andEdmund Hillaryextensive and Dr. V E.base; Fuchs join •'forces at. -

An Analysis of Fungal Propagules Transported to the Henryk Arctowski Antarctic Station

vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 269–278, 2013 doi: 10.2478/popore−2013−0015 An analysis of fungal propagules transported to the Henryk Arctowski Antarctic Station Anna AUGUSTYNIUK−KRAM 1,2, Katarzyna J. CHWEDORZEWSKA3, Małgorzata KORCZAK−ABSHIRE 3, Maria OLECH 3,4 and Maria LITYŃSKA−ZAJĄC 5 1 Centrum Badań Ekologicznych PAN w Dziekanowie Leśnym, ul. M. Konopnickiej 1, 05−092 Łomianki, Poland <aaugustyniuk−kram@cbe−pan.pl> 2 Instytut Ekologii i Bioetyki, Uniwersytet Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego w Warszawie, ul. Dewajtis 5, 01−815 Warszawa, Poland 3 Instytut Biochemii i Biofizyki PAN, Zakład Biologii Antarktyki, ul. Pawińskiego 5a, 02−106 Warszawa, Poland 4 Instytut Botaniki, Uniwersytet Jagielloński, ul. Kopernika 27, 31−512 Kraków, Poland 5 Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN w Krakowie, ul. Sławkowska 17, 31−016 Kraków, Poland Abstract: During three austral summer seasons, dust and soil from clothes, boots and equip− ment of members of scientific expeditions and tourists visiting the Polish Antarctic Station Henryk Arctowski were collected and analysed for the presence of fungal propagules. Of a to− tal of 60 samples, 554 colonies of fungi belonging to 19 genera were identified. Colonies of the genus Cladosporium, Penicillium and non−sporulating fungus (Mycelia sterilia) domi− nated in the examined samples. The microbiological assessment of air for the presence of fungi was also conducted at two points in the station building and two others outside the sta− tion. A total of 175 fungal colonies belonging to six genera were isolated. Colonies of the ge− nus Penicillium were the commonest in the air samples. The potential epidemiological conse− quences for indigenous species as a result of unintentional transport of fungal propagules to the Antarctic biome are discussed in the light of rapid climate change in some parts of the Ant− arctic and adaptation of fungi to extreme conditions. -

Parallel Precedents for the Antarctic Treaty Cornelia Lüdecke

Parallel Precedents for the Antarctic Treaty Cornelia Lüdecke INTRODUCTION Uninhabited and remote regions were claimed by a nation when their eco- nomic, political, or military values were realized. Examples from the North- ern and Southern hemispheres show various approaches on how to treat claims among rivaling states. The archipelago of Svalbard in the High Arctic and Ant- arctica are very good examples for managing uninhabited spaces. Whereas the exploration of Svalbard comprises about 300 years of development, Antarctica was not entered before the end of the nineteenth century. Obviously, it took much more time to settle the ownership of the archipelago in the so-called Sval- bard Treaty of 1920 than to find a solution for Antarctica and the existence of overlapping territorial claims by adopting the Antarctic Treaty of 1959. Why was the development at the southern continent so much faster? What is the es- sential difference between the situations obtaining in the two hemispheres? Was there a transposition of experiences from north to south? And did the Svalbard Treaty help to construct the Antarctic Treaty? Answers to these questions will be given by the analysis of single periods in the history of polar research, scientific networks, and special intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations with concomitant scientific or economic interests that merged in the twentieth century to arrange exploration and exploitation of polar regions on an interna- tional basis. EXPLORATION AND SCIENCE BEFORE WORLD WAR I SVALBARD After the era of whaling around the archipelago of Svalbard, the Norwe- gians were the only ones to exploit the area economically, including fishing, Cornelia Lüdecke, SCAR History Action since the 1850s, whereas Swedish expeditions starting in the same decade were Group, Fernpaßstraße 3, D- 81373 Munich, the first to explore the interior of the islands (Liljequist, 1993; Holland, 1994; Germany. -

Antartic Peninsula and Tierra Del Fuego: 100

ANTARCTIC PENINSULA & TIERRA DEL FUEGO BALKEMA – Proceedings and Monographs in Engineering, Water and Earth Sciences Antarctic Peninsula & Tierra del Fuego: 100 years of Swedish-Argentine scientific cooperation at the end of the world Edited by Jorge Rabassa & María Laura Borla Proceedings of “Otto Nordenskjöld’s Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1903 and Swedish Scientists in Patagonia: A Symposium”, held in Buenos Aires, La Plata and Ushuaia, Argentina, March 2–7, 2003. LONDON / LEIDEN / NEW YORK / PHILADELPHIA / SINGAPORE Cover photo information: “The Otto Nordenskjöld’s Expedition to Antarctic Peninsula, 1901–1903. The wintering party in front of the hut on Snow Hill, Antarctica, 30th September 1902. From left to right: Bodman, Jonassen, Nordenskjöld, Ekelöf, Åkerlund and Sobral. Photo: G. Bodman. From the book: Otto Nordenskjöld & John Gunnar Andersson, et al., “Antarctica: or, Two Years amongst the Ice of the South Pole” (London: Hurst & Blackett., 1905)”. Taylor & Francis is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 2007 Taylor & Francis Group plc, London, UK All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publishers. Although all care is taken to ensure the integrity and quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the author for any damage to property or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. -

Country Reports 2013

1 / 59 Table Of Content 1 Argentina (and South American Partners) __________________________________________ 3 2 Austria _______________________________________________________________________ 3 3 Canada _______________________________________________________________________ 7 4 China _______________________________________________________________________ 10 5 Denmark _____________________________________________________________________ 14 6 Finland ______________________________________________________________________ 15 7 France ______________________________________________________________________ 15 8 Germany ____________________________________________________________________ 17 9 Iceland ______________________________________________________________________ 21 10 Italy ________________________________________________________________________ 21 11 Japan ______________________________________________________________________ 24 12 Kyrgyzstan __________________________________________________________________ 25 13 Mongolia ___________________________________________________________________ 25 14 New Zealand ________________________________________________________________ 26 15 Norway _____________________________________________________________________ 26 16 Poland _____________________________________________________________________ 30 17 Portugal ____________________________________________________________________ 32 18 Romania ____________________________________________________________________ 32 19 Russia _____________________________________________________________________ -

Polar Explorers in "The Explorers' Club" Polarnicy W „Explorers' Club"

Ryszard W. SCHRAMM POLISH POLAR STUDIES Podlaska 8/2,60-623 Poznań XXVI Polar Symposium POLAND /ff еШУУУ*! Lublin, June 1999 POLAR EXPLORERS IN "THE EXPLORERS' CLUB" POLARNICY W „EXPLORERS' CLUB" In 1904 Henry C. Walsh, the writer, war correspondent and explorer of the Arc- tic suggested founding an informal club uniting various explorers. On 17 October 1905 seven citizens of the United States submitted a signed proposal to found "The Explorers' Club." Among them, besides Walsh, there was another even more famous explorer Dr. Frederick A.Cook, the physician during the expedition of "Belgica" in which our explorers - Henryk Arctowski and Antoni Bolesław Dobrowolski took part. The first meeting of the club took place a week later. Its first president was General A. W. Greely and its secretary was H. C. Walsh. The English word "ex- plorer" has two meenings: 1 - explorer, 2 - discoverer. It is expressed clearly in Ar- ticle II of the "Bylaws of the Explorer Club" - "Club Goals": "The Explorers' Club is a multidisciplinary, professional society dedicated to the advancement of field re- search, scientific exploration, resource conservation and the ideal that it is vital to preserve the instinct to explore." Therefore the range of E.C. members is wide from scientists-theoreticians to sportmen. For the latter not only field activity but also a journalistic one is important. In the first years of the Club activity the explorers played a predominant role in it. The second president of the Club was F. A. Cook (1907-1908) and then Robert E. Peary (1909-1911) elected again for two successive terms in 1913-1916. -

SECTION THREE: Historic Sites and Monuments in Antarctica

SECTION THREE: Historic Sites and Monuments in Antarctica The need to protect historic sites and monuments became apparent as the number of expeditions to the Antarctic increased. At the Seventh Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting it was agreed that a list of historic sites and monuments be created. So far 74 sites have been identified. All of them are monuments – human artifacts rather than areas – and many of them are in close proximity to scientific stations. Provision for protection of these sites is contained in Annex V, Article 8. Listed Historic Sites and Monuments may not be damaged, removed, or destroyed. 315 List of Historic Sites and Monuments Identified and Described by the Proposing Government or Governments 1. Flag mast erected in December 1965 at the South Geographical Pole by the First Argentine Overland Polar Expedition. 2. Rock cairn and plaques at Syowa Station (Lat 69°00’S, Long 39°35’E) in memory of Shin Fukushima, a member of the 4th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition, who died in October 1960 while performing official duties. The cairn was erected on 11 January 1961, by his colleagues. Some of his ashes repose in the cairn. 3. Rock cairn and plaque on Proclamation Island, Enderby Land, erected in January 1930 by Sir Douglas Mawson (Lat 65°51’S, Long 53°41’E) The cairn and plaque commemorate the landing on Proclamation Island of Sir Douglas Mawson with a party from the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition of 1929 31. 4. Station building to which a bust of V. I. Lenin is fixed, together with a plaque in memory of the conquest of the Pole of Inaccessibility by Soviet Antarctic explorers in 1958 (Lat 83°06’S, Long 54°58’E). -

National Antarctic Expedition Library

LIST OF BOOKS* BIOGRAPHICAL. TITLE. AUTHOR. PRESS· MARK. Francis Bacon Lord Macaulay w. L. R. Koolemans Beynen Charles Boissevain J. Isaac Bickerstaff Steele . w. l Prince Bismarck Charles Lowe . l J. 1 Charlotte Bronte Mrs. Gaskell . o. !. Burleigh, John Hampden, and Lord Macaulay w. i: Horace Walpole. ' History of Caliph Vathek . W. Beckford . W. I•: Colin CampbeU, Lord Clyde A. Forbes E. ·,.. :.. Miguel de Cervantes . H. E. Watts L. '! Earl of Chatham Lord Macaulay w. 1 Lord Clive C. Wilson . E. I· Christopher Columbus Sir Clements R. Markham J. ' Captain Cook Walter Besant . E. I Sir Roger de Coverley R. Steele and J. Addison . W. , Oliver Cromwell Frederic Harrison J. J; ; William Dampier W. Clark Russell J. ;j ·Two Years Before the Mast R. H. Dana . o. ·d · Charles Darwin . Francis Darwin . L. John Davis, the Navigator . Sir Clements R. Markham L. Sir Francis Drake Julian Corbett. E. ;,. Dundonald Ron. J. W. Fortescue J. Edward the First T. F. Tout . J, Queen Elizabeth E. S. Beesley . J. Emin Pasha (z v<ils.) George Schweitzer E. Michael Faraday Walter Jerrold. 0. Benjamin Franklin (Autobiography) . w. Sir John Franklin . Captain A. H. Markham J. · Frederick the Great (9 vols.) Thomas Carlyle E. ·: ' Edward Gibbon . John Murray E. '1 ' Goethe.· G. H. Lewes . ;l: E. 1. ,: ;.: ; 4 L.IST OF BOOKS. TITLE. AUTHOR. PRESS· MARK. Commodore Goodenough (Edited by his Widow) J. Charles George Gordon Sir William F. Butler E. Warren Hastings Sir Alfred Lyall J. Ditto Lord Macaulay W. Havelock . Archibald Forbes J. Prince Henry the Navigator C. R. Beazley L. Henry the Second Mrs. -

Admiralty Bay, King George Island

Measure 2 (2006) Annex Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Managed Area No.1 ADMIRALTY BAY, KING GEORGE ISLAND Introduction Admiralty Bay is an area of outstanding environmental, historical, scientific, and aesthetic values. It was first visited by sealers and whalers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and relics from these periods still remain. The area is characterized by magnificent glaciated mountainous landscape, varied geological features, rich sea-bird and mammal breeding grounds, diverse marine ecosystems, and terrestrial plant habitats. Scientific research in Admiralty Bay in post IGY times has been performed in a more permanent way for some three decades now. The studies on penguins have been undertaken continuously in the area for 28 years, and is the longest ever done in Antarctica. Admiralty Bay also has one of the longest historical series of meteorological data collected for the Antarctic Peninsula, one of the areas of the planet most sensitive to climate change. Admiralty Bay has become a site of increasingly diverse human activities, which are continuously growing and becoming more complex. Along the last 30 years, more stations were settled and have grown in area, and visitors increased in numbers per year, from a few hundreds to over 3000. Better planning and co- ordination of existing and future activities will help to avoid or to reduce the risk of mutual interference and minimize environmental impacts, thus providing an effective mechanism for the conservation of the valuable features that characterize the area. Five parties: Poland, Brazil, United States, Peru and Ecuador have active research programmes in the area. Poland and Brazil operate two all-year round stations (Poland: Henryk Arctowski Station at Thomas Point; and Brazil: Comandante Ferraz Antarctic Station at Keller Peninsula). -

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition Under the Command of A

THE KuiAN mmm ijpiditiiin UNDER THE COMMAND OF A. DE GERLACHE DE GOMERY SUMMARY REPORT OF THE VOYAGE OF THE " BELGICA „ IN 1897-1898-1899 BRUSSELS - HAYEZ, PRINTER TO THE ROYAL ACADEMY OF BELGIUM Rue do Louvain, lia 1904 16 51 6 THE BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION UNDER THE COSIMAND OF A. DE GERLACHE DE GOMERY THE BELGUN mmm immm UNDER THE COMMAND OF A. DE GERLACHE de GOMERY SUMMARY REPORT OF THE VOYAGE OF THE " BELGICA „ IN 1897-1898-1899 BRUSSELS HAYEZ, PRINTER TO THE ROYAL ACADEMY OF BELGIUM Hue de l^ou'^aixi, 113 1904 13 H 1 1 G-z \ THE BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION The Belgian Antarctic Expedition owes its initiative to the enterprise of M. Adrien de Geilache de Gomery, lieutenant in the Belgian navy, who, on the completion of its organisation, also assumed the command. As early as the beginning of 1894, M. de Gei"lache communicated to M. Du Fief, secretary to the Geographical Society of Belgium, his scheme of a Belgian expedition to the South Polar regions. The project called forth an enthusiastic response from the Geographical Society and was soon crowned w^ith the patronage of H. R. H. Prince Albert of Belgium. A subscription list inaugurated by the Geogra])hical Society became promptly graced by . the names of many generous donors. Among the more 5 strenuous supporters of the venture may be named ^ Lieut. -General Brialmont, MM. Delaite, Du Fief, Leo Hj Errera, Houzeau de Lehaie, Charles and Eugene Lagrange,igrange Lancaster, Commandant Lemaire, MM. Pel- ^ seneer, Renard, Ernest Solvay, Count Hippolyte (vj^ d'Ursel, Van Beneden, Mesdames de Ronge and Osterrieth.