Comforting Sentences from the Warming Room at Inchcolm Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

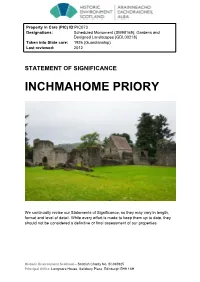

Inchmahome Priory Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC073 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90169); Gardens and Designed Landscapes (GDL00218) Taken into State care: 1926 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE INCHMAHOME PRIORY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH INCHMAHOME PRIORY SYNOPSIS Inchmahome Priory nestles on the tree-clad island of Inchmahome, in the Lake of Menteith. It was founded by Walter Comyn, 4th Earl of Menteith, c.1238, though there was already a religious presence on the island. -

The Case for a Marine Act for Scotland the Tangle of the Forth

The Case for a Marine Act for Scotland The Tangle of the Forth © WWF Scotland For more information contact: WWF Scotland Little Dunkeld Dunkeld Perthshire PH8 0AD t: 01350 728200 f: 01350 728201 The Case for a Marine Act for Scotland wwf.org.uk/scotland COTLAND’S incredibly Scotland’s territorial rich marine environment is waters cover 53 per cent of Designed by Ian Kirkwood Design S one of the most diverse in its total terrestrial and marine www.ik-design.co.uk Europe supporting an array of wildlife surface area Printed by Woods of Perth and habitats, many of international on recycled paper importance, some unique to Scottish Scotland’s marine and WWF-UK registered charity number 1081274 waters. Playing host to over twenty estuarine environment A company limited by guarantee species of whales and dolphins, contributes £4 billion to number 4016274 the world’s second largest fish - the Scotland’s £64 billion GDP Panda symbol © 1986 WWF – basking shark, the largest gannet World Wide Fund for Nature colony in the world and internationally 5.5 million passengers and (formerly World Wildlife Fund) ® WWF registered trademark important numbers of seabirds and seals 90 million tonnes of freight Scotland’s seas also contain amazing pass through Scottish ports deepwater coral reefs, anemones and starfish. The rugged coastline is 70 per cent of Scotland’s characterised by uniquely varied habitats population of 5 million live including steep shelving sea cliffs, sandy within 0km of the coast and beaches and majestic sea lochs. All of 20 per cent within km these combined represent one of Scotland’s greatest 25 per cent of Scottish Scotland has over economic and aesthetic business, accounting for 11,000km of coastline, assets. -

Catalogue Description and Inventory

= CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION AND INVENTORY Adv.MSS.30.5.22-3 Hutton Drawings National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © 2003 Trustees of the National Library of Scotland = Adv.MSS.30.5.22-23 HUTTON DRAWINGS. A collection consisting of sketches and drawings by Lieut.-General G.H. Hutton, supplemented by a large number of finished drawings (some in colour), a few maps, and some architectural plans and elevations, professionally drawn for him by others, or done as favours by some of his correspondents, together with a number of separately acquired prints, and engraved views cut out from contemporary printed books. The collection, which was previously bound in two large volumes, was subsequently dismounted and the items individually attached to sheets of thick cartridge paper. They are arranged by county in alphabetical order (of the old manner), followed by Orkney and Shetland, and more or less alphabetically within each county. Most of the items depict, whether in whole or in part, medieval churches and other ecclesiastical buildings, but a minority depict castles or other secular dwellings. Most are dated between 1781 and 1792 and between 1811 and 1820, with a few of earlier or later date which Hutton acquired from other sources, and a somewhat larger minority dated 1796, 1801-2, 1805 and 1807. Many, especially the engravings, are undated. For Hutton’s notebooks and sketchbooks, see Adv.MSS.30.5.1-21, 24-26 and 28. For his correspondence and associated papers, see Adv.MSS.29.4.2(i)-(xiii). -

Welcome to Walter Bower House

Covid edition Welcome to Walter Bower House A quick start guide to working at WBH – the home of Professional Services at the University of St Andrews Who was Walter Bower? Walter Bower was one of the earliest historians of Scotland, a prelate, and a public figure at the heart of power in the early fifteenth century. Bower is a distinguished and significant contributor to our understanding of our past. Bower was born in the decades preceding the foundation of the University, in East Lothian, which at that time looked to St Andrews as the centre of ecclesiastical power in Scotland. Around the turn of the fifteenth century Bower joined the canons who served St Andrews Cathedral, and he witnessed the founding of the University and the arrival of the papal bulls from Avignon in 1414. One of our first students, Bower studied canon law and later took a degree in theology. By 1417 he had become Abbot of Inchcolm Abbey in the Firth of Forth, where he spent his career. As a leading prelate Bower was heavily involved in Scottish political and religious life, attending parliaments and serving the king’s administration. He was a man of formidable skill in public life, but also a man of intellectual depth and considerable talent in letters. Bower’s gift to Scotland came in the form of the Scotichronicon, the first developed narrative of the history of Scotland from the Creation until Bower’s present day. It is a major work, in 16 books, written in Latin. It took most of the 1440s to compile and ended with Bower’s proud exclamation: “Christ! He is not a Scot who is not pleased with this book.” Importantly to the University, Bower’s Scotichronicon is the only eye-witness account of our foundation which has survived. -

Mary, Queen of Scots Detail View of Hertford's Drawing, Online Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

ENGAGED, MARRIED and WIDOWED 0. ENGAGED, MARRIED and WIDOWED - Story Preface 1. ENGAGED, MARRIED and WIDOWED 2. DEATHS of RIZZIO and DARNLEY 3. BAD JUDGMENT and ABDICATION 4. ESCAPE from LOCH LEVEN 5. "SAFELY KEPT and GUARDED" 6. IMPACT of the BABINGTON PLOT 7. MARY DEFENDS HERSELF 8. "FOR the CAUSE of the TRUE RELIGION" 9. EYEWITNESS REPORTS a BEHEADING 10. THE CASE of the BLACK PEARLS 11. MORE BACKGROUND on MARY To protect his Kingdom, Henry VIII wanted a political alliance with Scotland. He wanted Mary Stewart to wed his frail son, Prince Edward (who, when he became King, would be Edward VI). The Scottish Parliament did not approve that arrangement. Catholic forces inside Scotland also had other ideas. They believed that Mary should wed the French heir, the Dauphin Francis. Mary's mother - a French princess - agreed. Henry VIII was extremely upset when Scotland's Parliament would not approve the Treaty of Greenwich (setting forth the terms of a marriage between the two youngsters). So angry was Henry that he fought a war over the issue (now called the "Rough Wooing" War). He sent his troops to Scotland with this directive: Put all to fire and sword. "All" included women and children. With fighting all around, Mary of Guise (then serving as Queen Regent) was worried about her daughter's safety. Would English soldiers try to kidnapp her? To avoid such a disaster, Mary hid her daughter inside Inchcolm Abbey (founded in the 12th century) located on the island of Inchcolm (in Scotland's Firth of Forth). There, the five-year-old child would be safe with the monks (and away from English soldiers). -

Download Download

II.—An Account of St Columbd's Abbey, Inchcolm. Accompanied with Plans, ^c.1 (Plates IV.-VL) By THOMAS ARNOLD, Esq., Architect, M.R.LB.A, Lond. [Communicated January 11, 1869, with an Introductory Note.] NEAR the northern shores of the Firth of Forth, and within sight of Edin- burgh, lies the island anciently known as Emona, and in later times as Inchcolm, the island of St Columba. It is of very small extent, scarcely over half a mile in length, and 400 feet in width at its broadest part. The tide of commerce and busy life which ebbs and flows around has left the little inch in a solitude as profound as if it gemmed the bosom of some Highland loch, a solitude which impresses itself deeply on the stranger who comes to gaze on its ruined, deserted, and forgotten Abbey. Few even of those who visit the island from the beautiful village of Aberdour, close to it, know anything of its history, and as few out of sight of the island know of its existence at all. But although now little known beyond the shores of the Forth, Inchcolm formerly held a high place in the veneration of the Scottish people as the cradle of the religious life of the surrounding districts, and was second only to lona as a holy isle in whose sacred soil it was the desire of many generations to be buried. It numbered amongst its abbots men of high position and learning. Noble benefactors enriched it with broad lands and rich gifts, and its history and remains, like the strata of some old mountain, bear the marks of every great wave of life which has passed over our country. -

Aberdeen and St Andrews Nicola Royan

St Andrews and Aberdeen 20: Aberdeen and St Andrews Nicola Royan (University of Nottingham) Introduction A thousand thre hundreth fourty and nyne Fra lichtare was þe suet Virgyne, lichtare – delivered of a child In Scotland þe first pestilens Begouth, of sa gret violens That it wes said of liffand men liffand - living The third part it distroyit þen; And eftir þat in to Scotland A зere or mare it wes wedand. wedand - raging Before þat tyme wes neuer sene In Scotland pestilens sa keyne: keyne- keen For men, and barnis and wemen, It sparit nocht for to quell then.1 Thus Andrew of Wyntoun (c.1350-c.1422) recorded the first outbreak of the Black Death in Scotland. Modern commentators set the death toll at between a quarter and a third of the population, speculating that Scotland may not have suffered as badly as some other regions of Europe.2 Nevertheless, it had a significant effect. Fordun’s Gesta discusses its symptoms, but its full impact on St Andrews comes to us through Walter Bower’s lament on the high loss among the cathedral’s canons.3 In Aberdeen, in contrast, there survive detailed burgh records regarding the process of isolating sufferers: that these relate to the outbreak of 1498 indicates that the burgesses had learned some epidemiological lessons from previous outbreaks and were willing to act on corporate responsibility.4 These responses nicely differentiate the burghs. On the north-east coast of Fife, St Andrews was a small episcopal burgh. From the top of St Rule’s tower (see above), it is easy to see to the north, the bishops’ castle substantially rebuilt by Bishop Walter Traill (1385-1401), the mouth of the river Eden, and beyond that the Firth of Tay; to the west, away from the sea, the good farmland in the rolling hills and valley of the Howe of Fife; to the east, the present harbour. -

![1 “To [My History], Which in Its Scottish Dress Could Interest Scotsmen](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8913/1-to-my-history-which-in-its-scottish-dress-could-interest-scotsmen-1378913.webp)

1 “To [My History], Which in Its Scottish Dress Could Interest Scotsmen

1 “To [my history], which in its Scottish dress could interest Scotsmen only, I have, with some trouble, given the power to speak to all through the medium of Latin.”1 John Lesley’s characterisation of his own De Origine et Moribus Scotorum (1578) identifies two important and obvious features of Scottish Latinitas: the breadth of audience, and the Scottish participation in European culture. Even in Lesley’s account, however, there may be discerned an element of defensiveness, in the need to court an audience for Scottish affairs using an international language. While such a position is not really tenable, given the interest in and importance of Lesley’s queen to European affairs, nevertheless it could be argued that a similar defensiveness has coloured the scholarship of Scottish Latinitas for several, far more recent, decades.2 This collection challenges that perspective, by exploring without apology aspects of Scottish Latinitas from the eighth century to the seventeenth, and opening that great area of Scottish culture to further scholarly scrutiny, to support its rediscovery in anthologies and histories, and crucially to embed it in our understanding of Scottish culture from the eighth to the eighteenth centuries, rather than isolating it as a curious and additional cousin to the vernacular cultures.3 That a battle standard for new approaches to Scottish Latinitas should be raised by a volume of essays with its foundations in the 13th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Language and Literature, held in Padua -

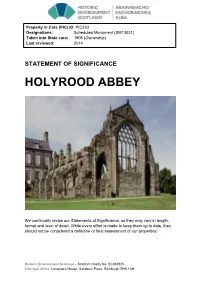

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

THE DEVELOPMENT of INCHCOLM ABBEY. by J. WILSON PATERSON, M.V.O., M.B.E., F.S.A.Scot

III. THE DEVELOPMENT OF INCHCOLM ABBEY. BY J. WILSON PATERSON, M.V.O., M.B.E., F.S.A.ScoT. Before Inchcol s disfigure mwa e fortification th y b d s erected during the war it was perhaps the most beautiful of the islands in the Forth Fig. 1. Inchcolm Abbey, before 1883, from the south. (fig. 1). The rocky promontories at the east and west tail off and merge int onarroa w isthmus, formin gnaturaa l harbounorte th n ho rshore . On this narrow strip of land, sheltered from the east and west, stand the mose th f tremaino interestine on f so g building Scotlandn si ; interesting not only on account of its historical and romantic associations but also in 228 PROCEEDING E SOCIETYTH F O S , MARC , 1926H8 . regard to the buildings themselves, as they constitute, without excep- tion e onlth , y monastery extan Scotlann i t d which show complete th s e arrangemen establishmene th f to t (fig. 8) . Althoug edifice welho th s s le i t previouslpreserve no s wa t di y possible —owin conversioe th o gt largee th f nro portio monastie th f no c buildings int omodera n dwelling-house—to determin e extenvarioue eth th f o t s office their o s r true function. Referenc e literaturth subjece o et th n eo t doe t helsno p matters apar, as , t fro historicae mth l notes descriptioe th , n of the buildings in the various books is for the most part contradictory and unconvincing t untino s l 1924wa t I , .whe Eare n th f Mora lo y placed the remains under the guardianship of H.M. -

In Fifteenth-Century Scotland

Edinburgh Research Explorer Commemorating the Battle of Harlaw (1411) in Fifteenth-Century Scotland Citation for published version: Boardman, S 2018, Commemorating the Battle of Harlaw (1411) in Fifteenth-Century Scotland. in S Butler & KJ Kesselring (eds), Crossing Borders: Boundaries and Margins in Late Medieval and Early Modern Britain: Essays in Honour of Cynthia J. Neville., 3, Later Medieval Europe, vol. 17, Brill, Leiden, pp. 61-82. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Crossing Borders: Boundaries and Margins in Late Medieval and Early Modern Britain General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Commemorating the Battle of Harlaw (1411) in Fifteenth-Century Scotland Stephen Boardman On 24 July 1411 a fierce battle took place on the low plateau of Harlaw in the parish of Chapel of Garioch, near Inverurie in north-eastern Scotland.1 The opposing forces were led by Donald, Lord of the Isles, who brought to the field a large army drawn chiefly from his Hebridean, west-coast and central Highland lordships, and Alexander Stewart, earl of Mar, at the head of a host raised from Mar, Buchan, Angus, and the burgh of Aberdeen.