Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Cornus Kousa Kousa Dogwood1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-191 November 1993 Cornus kousa Kousa Dogwood1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Kousa Dogwood grows 15 to 20 feet tall and has beautiful exfoliating bark, long lasting flowers, good fall color, and attractive fruit (Fig. 1). Branches grow upright when the tree is young, but appear in horizontal layers on mature trees. The crown eventually grows wider than it is tall on many specimens. It would be difficult to use too many Kousa Dogwoods. The white, pointed bracts are produced a month later than Flowering Dogwood and are effective for about a month, sometimes longer. The red fruits are edible and they look like a big round raspberry. Birds devour the fruit quickly. Fall color varies from dull red to maroon. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Cornus kousa Pronunciation: KOR-nus KOO-suh Common name(s): Kousa Dogwood, Chinese Dogwood, Japanese Dogwood Family: Cornaceae USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 8 (Fig. 2) Figure 1. Young Kousa Dogwood. Origin: not native to North America Uses: container or above-ground planter; near a deck DESCRIPTION or patio; screen; specimen Availability: generally available in many areas within Height: 15 to 20 feet its hardiness range Spread: 15 to 20 feet Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more or less identical crown forms Crown shape: round Crown density: dense Growth rate: slow 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-191, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Davidia Involucrata Handkerchief Tree

Davidia involucrata Handkerchief Tree Davidia involucrata is the only member of its genus but there are two varieties separated by their leaves, var. involucrata which whose leaves are short haired on the underside and var. vilmoriniana which have hairless leaves. A small/medium sized tree it is most well known for its astonishing white, large bracts that hang like pinched handkerchiefs from its branches in May. The foliage is midsized and heart shaped, of a attractive green colour in summer turning shades of orange and yellow in winter with young foliage in spring having a red/purple colour and a spicy, incense fragrance. Small inedible pear shaped fruits are produced in the spring. Davidia involucrata 4m Plant Profile Name: Davidia involucrata Common Name: Handkerchief Tree / Dove Tree Family: Nyssaceae Height: Up to above 12 metres Width: Up to 6-8 metres Demands: Sun or light shade in a sheltered position Soil: All soils tolerated but prefers well drained or moist but well drained Foliage: Deciduous Fruit: Hard Nut with green husk Flowers of the Davidia involucrata vilmoriniana Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DX. Tel: 01767 26 26 36 www.deepdale-trees.co.uk Davidia involucrata Handkerchief Tree The Davidia involucrata is named after the French missionary and botanist Father Armand David who was also the first westerner to report a sighting of a panda! Summer foliage Container Grown 3-4m Davida involucrata Davidia involucrata 3.5-4m in winter Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DX. Tel: 01767 26 26 36 www.deepdale-trees.co.uk. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Breeding Powdery Mildew Resistant Dogwoods and More at Rutgers University© T.J

1 11-B-Molnar-Tom-IPPS-2018 Breeding Powdery Mildew Resistant Dogwoods and More at Rutgers © University T.J. Molnar Department of Plant Biology and Pathology, The School of Environmental and Biological Sciences, Rutgers University, 59 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901, USA. Email: [email protected] Keywords: Holly, Ilex sp., Cornus sp., hazelnuts, Corylus sp., Erysiphe pulchra , woody ornamental breeding, clonal propagation, budding, seedlings, molecular tools, novel cultivars INTRODUCTION The Rutgers University Woody Ornamental Breeding Program began in 1960 under the direction of Dr. Elwin Orton. The early focus of the program was the breeding of hollies (Ilex sp.), with work on big-bracted dogwoods (Cornus sp.) starting in the 1970s. The program continues today with the addition of hazelnuts (Corylus sp.) for nut production and ornamentals. Over 40 cultivars have been released since the initiation of the program, and a number have become widely grown in the nursery and landscape trade. A list of releases can be found in Molnar and Capik (2013). The most noteworthy Rutgers introductions, at least from the perspective of plants propagated and sold thus far, are likely the hybrid dogwoods. These were largely the results of crossing Cornus kousa with C. florida to create a series of unique plants (subsequently named Cornus × rutgersensis [Mattera et al., 2015]) that combined traits of both parental species to create attractive, high-value landscape specimens. The hybrids generally exhibit increased vigor over their parental species and better drought tolerance than C. florida. However, their most important attribute is likely their resistance or increased tolerance to 1 2 diseases such as dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva) and powdery mildew [(PM), Erysiphe pulchra) (Hibben and Daughtrey, 1998; Ranney et al., 1995)]. -

Cornus Kousa (Japanese Flowering Dogwood)

Cornus kousa (Japanese Flowering Dogwood) Cornus kousa is a small tree or shrub, not usually exceeding 6m. It has a slow to medium growth rate and an upright habit, broadening with age. Cream flowers appear in early summer and last for several weeks, turning a slight pinkish brown as they get older. These are actually the bracts surrounding the true flowers which are inconspicu- ous. Strawberry like fruits are produced which are edible but not overly tasty! The foliage is green and ovate through the summer changing to reds June and purples in autumn. Cornus kousa is more robust than the other flower- ing dogwood, Cornus florida and is also resist- 2011 ant the dogwood anthracnose disease making it a popular alternative. Plant Profile Name: Cornus kousa Common Name: Japanese Flowering Dogwood or Kousa dogwood Family: Cornaceae Height: up to 6m Shape: upright when young but broadens with age Demands: Full sun or partial shade, not tolerant of chalky soils Flowers: Cream in early summer Fruit: 2-3cm, strawberry like fruits Autumn Colour: Foliage colours reds and purples Cornus kousa 4.0-4.5m Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DX. Tel: 01767 26 26 36 www.deepdale-trees.co.uk Cornus kousa (Japanese Flowering Dogwood) Yamaboushi or Japanese Flowering Dogwood ヤマボウシ Cornus kousa Cornus kousa Chinensis 4.0-5.0m Cornus kousa supplied to RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2011 2.0-2.5m multistem Autumn colour Homebase – Thomas Hoblyn Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DX. Tel: 01767 26 26 36 www.deepdale-trees.co.uk. -

A Critically Endangered Plant Species Endemic to South-West China

Integrated conservation for Parakmeria omeiensis (Magnoliaceae), a Critically Endangered plant species endemic to south-west China D AOPING Y U ,XIANGYING W EN,CEHONG L I ,TIEYI X IONG,QIXIN P ENG X IAOJIE L I ,KONGPING X IE,HONG L IU and H AI R EN Abstract Parakmeria omeiensis is a Critically Endangered tree attractive and large, and their seed arils are orange, making species in the family Magnoliaceae, endemic to south-west the tree an attractive ornamental plant. However, the species China. The tree is functionally dioecious, but little is known has a restricted range. It has been considered a Grade-I about the species’ status in the wild. We investigated the Key-Protected Wild Plant Species in China since and range, population size, age structure, habitat characteristics has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the and threats to P. omeiensis. We located a total of individuals IUCN Red List since (China Expert Workshop, ), in two populations on the steep slopes of Mount Emei, Sichuan the Chinese Higher Plants Red List since (Yin, ), and province, growing under the canopy of evergreen broadleaved the Red List of Magnoliaceae since (Malin et al., ). forest in well-drained gravel soil. A male-biased sex ratio, lack The tree has also been identified as a plant species with an of effective pollinating insects, and habitat destruction result extremely small population (Ren et al., ; State Forestry in low seed set and poor seedling survival in the wild. We Administration of China, ). have adopted an integrated conservation approach, including Parakmeria includes five species (P. -

Development of EST-SSR Markers in the Relict Tree Davidia Involucrata (Davidiaceae) Using Transcriptome Sequencing

Development of EST-SSR markers in the relict tree Davidia involucrata (Davidiaceae) using transcriptome sequencing Z.C. Long1,2, A.W. Gichira1,2, J.M. Chen1, Q.F. Wang1 and K. Liao1 1Key Laboratory of Plant Germplasm Enhancement and Specialty Agriculture, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China 2Life Science College, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Corresponding author: K. Liao E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 15 (4): gmr15048539 Received February 11, 2016 Accepted March 28, 2016 Published October 17, 2016 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/gmr15048539 Copyright © 2016 The Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) 4.0 License. ABSTRACT. Davidia involucrata, reputed to be a “living fossil” in the plant kingdom, is a relict tree endemic to China. Extant natural populations are diminishing due to anthropogenic disturbance. In order to understand its ability to survive in a range of climatic conditions and to design conservation strategies for this endangered species, we developed genic simple sequence repeats (SSRs) from mRNA transcripts. In total, 142,950 contigs were assembled. Of these, 30,411 genic SSR loci were discovered and 12,208 primer pairs were designed. Dinucleotides were the most common (77.31%) followed by trinucleotides (16.44%). Thirteen randomly selected primers were synthesized and validated using 24 individuals of D. involucrata. The markers displayed high polymorphism with the number of alleles per locus ranging from 3 to Genetics and Molecular Research 15 (4): gmr15048539 Z.C. Long et al. -

Bgci's Plant Conservation Programme in China

SAFEGUARDING A NATION’S BOTANICAL HERITAGE – BGCI’S PLANT CONSERVATION PROGRAMME IN CHINA Images: Front cover: Rhododendron yunnanense , Jian Chuan, Yunnan province (Image: Joachim Gratzfeld) Inside front cover: Shibao, Jian Chuan, Yunnan province (Image: Joachim Gratzfeld) Title page: Davidia involucrata , Daxiangling Nature Reserve, Yingjing, Sichuan province (Image: Xiangying Wen) Inside back cover: Bretschneidera sinensis , Shimen National Forest Park, Guangdong province (Image: Xie Zuozhang) SAFEGUARDING A NATION’S BOTANICAL HERITAGE – BGCI’S PLANT CONSERVATION PROGRAMME IN CHINA Joachim Gratzfeld and Xiangying Wen June 2010 Botanic Gardens Conservation International One in every five people on the planet is a resident of China But China is not only the world’s most populous country – it is also a nation of superlatives when it comes to floral diversity: with more than 33,000 native, higher plant species, China is thought to be home to about 10% of our planet’s known vascular flora. This botanical treasure trove is under growing pressure from a complex chain of cause and effect of unprecedented magnitude: demographic, socio-economic and climatic changes, habitat conversion and loss, unsustainable use of native species and introduction of exotic ones, together with environmental contamination are rapidly transforming China’s ecosystems. There is a steady rise in the number of plant species that are on the verge of extinction. Great Wall, Badaling, Beijing (Image: Zhang Qingyuan) Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) therefore seeks to assist China in its endeavours to maintain and conserve the country’s extraordinary botanical heritage and the benefits that this biological diversity provides for human well-being. It is a challenging venture and represents one of BGCI’s core practical conservation programmes. -

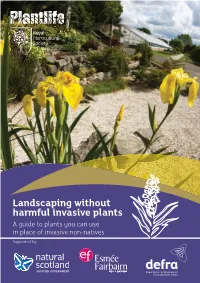

Landscaping Without Harmful Invasive Plants

Landscaping without harmful invasive plants A guide to plants you can use in place of invasive non-natives Supported by: This guide, produced by the wild plant conservation Landscaping charity Plantlife and the Royal Horticultural Society, can help you choose plants that are without less likely to cause problems to the environment harmful should they escape from your planting area. Even the most careful land managers cannot invasive ensure that their plants do not escape and plants establish in nearby habitats (as berries and seeds may be carried away by birds or the wind), so we hope you will fi nd this helpful. A few popular landscaping plants can cause problems for you / your clients and the environment. These are known as invasive non-native plants. Although they comprise a small Under the Wildlife and Countryside minority of the 70,000 or so plant varieties available, the Act, it is an offence to plant, or cause to damage they can do is extensive and may be irreversible. grow in the wild, a number of invasive ©Trevor Renals ©Trevor non-native plants. Government also has powers to ban the sale of invasive Some invasive non-native plants might be plants. At the time of producing this straightforward for you (or your clients) to keep in booklet there were no sales bans, but check if you can tend to the planted area often, but it is worth checking on the websites An unsuspecting sheep fl ounders in a in the wider countryside, where such management river. Invasive Floating Pennywort can below to fi nd the latest legislation is not feasible, these plants can establish and cause cause water to appear as solid ground. -

And Lepidoptera Associated with Fraxinus Pennsylvanica Marshall (Oleaceae) in the Red River Valley of Eastern North Dakota

A FAUNAL SURVEY OF COLEOPTERA, HEMIPTERA (HETEROPTERA), AND LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH FRAXINUS PENNSYLVANICA MARSHALL (OLEACEAE) IN THE RED RIVER VALLEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By James Samuel Walker In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Entomology March 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School North DakotaTitle State University North DaGkroadtaua Stet Sacteho Uolniversity A FAUNAL SURVEYG rOFad COLEOPTERA,uate School HEMIPTERA (HETEROPTERA), AND LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH Title A FFRAXINUSAUNAL S UPENNSYLVANICARVEY OF COLEO MARSHALLPTERTAitl,e HEM (OLEACEAE)IPTERA (HET INER THEOPTE REDRA), AND LAE FPAIDUONPATLE RSUAR AVSESYO COIFA CTOEDLE WOIPTTHE RFRAA, XHIENMUISP PTENRNAS (YHLEVTAENRICOAP TMEARRAS),H AANLDL RIVER VALLEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA L(EOPLIDEAOCPTEEAREA) I ANS TSHOEC RIAETDE RDI VWEITRH V FARLALXEIYN UOSF P EEANSNTSEYRLNV ANNOICRAT HM DAARKSHOATALL (OLEACEAE) IN THE RED RIVER VAL LEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA ByB y By JAMESJAME SSAMUEL SAMUE LWALKER WALKER JAMES SAMUEL WALKER TheThe Su pSupervisoryervisory C oCommitteemmittee c ecertifiesrtifies t hthatat t hthisis ddisquisition isquisition complies complie swith wit hNorth Nor tDakotah Dako ta State State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of University’s regulations and meetMASTERs the acce pOFted SCIENCE standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: David A. Rider DCoa-CCo-Chairvhiadi rA. -

Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections

Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections By Emily Beech, Kirsty Shaw and Meirion Jones June 2015 Recommended citation: Beech, E., Shaw, K., & Jones, M. 2015. Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections. BGCI. Acknowledgements BGCI gratefully acknowledges the many botanic gardens around the world that have contributed data to this survey (a full list of contributing gardens is provided in Annex 2). BGCI would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in the promotion of the survey and the collection of data, including the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Yorkshire Arboretum, University of Liverpool Ness Botanic Gardens, and Stone Lane Gardens & Arboretum (U.K.), and the Morton Arboretum (U.S.A). We would also like to thank contributors to The Red List of Betulaceae, which was a precursor to this ex situ survey. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) BGCI is a membership organization linking botanic gardens is over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. www.bgci.org FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) FFI, founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, based on sound science and take account of human needs. www.fauna-flora.org GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) GTC is undertaken through a partnership between BGCI and FFI, working with a wide range of other organisations around the world, to save the world’s most threated trees and the habitats which they grow through the provision of information, delivery of conservation action and support for sustainable use.