Early Music Performer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21214Booklet.Pdf

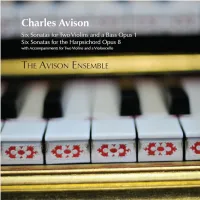

Charles Avison (1709-1770) – Trio Sonatas, op. 1 CD1 No. 1 in chromatic Dorian mode [8.35] No. 4 in Dorian mode [8.15] 01 Adagio - andante [2.04] 13 Largo [1.58] 02 Allegro [2.10] 14 Allegro [2.09] 03 Dolce [1.44] 15 Adagio [1.19] 04 Allegro [2.37] 16 Allegro [2.49] No. 2 in G minor [10.23] No. 5 in E minor [6.32] 05 Andante [2.43] 17 Adagio [1.35] 06 Allegro [3.59] 18 Allegro [1.37] 07 Adagio [1.12] 19 Adagio [1.08] 08 Allegro [2.29] 20 Allegro [2.12] No. 3 in G minor [6.29] No. 6 in D major [6.20] 09 Largo [1.53] 21 Andante [1.46] 10 Allegro [1.34] 22 Allegro [2.13] 11 Adagio [1.14] 23 Adagio [0.33] 12 Allegro [1.48] 24 Giga: Allegro [1.48] Members of the Avison Ensemble: Total duration (CD1) 47.21 Pavlo Beznosiuk (violin) Caroline Balding (violin) Richard Tunnicliffe (cello) Robert Howarth (chest organ) Charles Avison (1709-1770) – Keyboard Sonatas, op. 8 CD2 No. 1 in A major [8.20] No. 4 in B flat major [7.28] 01 Andante cantabile [3.36] 08 Andante [2.53] 02 Presto [4.44] 09 Presto [4.35] No. 2 in C major [9.06] No. 5 in G minor [8.10] 03 Allegro [4.37] 10 Andante [3.33] 04 Interludio andante [1.24] 11 Presto [4.37] 05 Allegro [3.05] No. 6 in G major [7.32] No. 3 in D major [8.33] 12 Aria andante – allegro 06 Marcia andante [4.07] 07 Aria allegretto [4.26] Robert Howarth (harpsichord) Total duration (CD2) 49.48 Pavlo Beznosiuk (violin) Caroline Balding (violin) Richard Tunnicliffe (cello) Pavlo Beznosiuk plays a violin from the Hill workshop, c.1760 Caroline Balding plays a violin of the Stainer school, c. -

Musicweb International December 2020 NAXOS RELEASES: LATE

NAXOS RELEASES: LATE 2020 By Brian Wilson It may be that I’ve been particularly somnolent recently, but a particularly fruitful series of Naxos releases in late 2020 has made me take notice of what I’ve been missing earlier this year, so I’ve included some of them, too. Index [page numbers in brackets] ALYABIEV Piano Trios (+ GLINKA, RUBINSTEIN: Russian Piano Trios 1) [5] Corelli’s Band: Violin Sonatas by Corelli and followers [2] FREDERICK II (Frederick The Great): Flute Sonatas [4] GERSHWIN Concerto in F (+ PISTON Symphony No.5, etc.) [11] GLINKA Trio pathétique (see ALYABIEV) [5] GOMPPER Cello Concerto, Double Bass Concerto, Moonburst [15] Michael HAYDN Missa Sancti Nicolai Tolentini; Vesperæ [5] HUMPERDINCK Music for the Stage [7] KORNGOLD Suite, Op.23; Piano Quintet [10] Laudario di Cortona excerpts (see PÄRT) [13] NOVÁK V Tatrách (In the Tatra Mountains); Lady Godiva; O věčné touze (Eternal Longing) [8] - Jihočeská suita (‘South Bohemian Suite’); Toman a lesní panna (‘Toman and the Wood Nymph’) [9] PÄRT And I heard a voice…, etc. ( … and … with SHAW, WOLFE, Laudario di Cortona) [13] PISTON Symphony No.5 (see GERSHWIN) [11] RUBINSTEIN Piano Trio (see ALYABIEV) [5] RUTTER Anthems, Hymns and Gloria for Brass Band [12] SCHMITT La Tragédie de Salomé, etc. [8] SCHUMANN Robert and Clara Music for violin and piano [6] VILLA-LOBOS Complete Symphonies [9] WALTON Piano Quintet and other Chamber Works with Violin and Piano [11] WEINBERG Clarinet Concerto; Clarinet Sonata; Chamber Symphony No.4 [12] WIDOR Organ Symphonies 4 (Nos. 8 and 10) [7] * The Art of Classical Guitar Transcription Christophe Dejour [15] Carmina predulcia (C15 Songbook) [1] Christmas Concertos [2] Heaven Full of Stars (contemporary choral) [13] Stille Nacht: Christmas Carols for Guitar [14] *** Carmina predulcia (‘very sweet songs’) is a recording of music from the fifteenth-century Schedelschen Liederbuch (Schedel Songbook). -

North York Moors Chamber Music Festival

North York Moors Chamber Music Festival ‘ Along the Danube’ 12-25 August 2012 www.northyorkmoorsfestival.com Patron Sir Marcus WorSley Introduction Welcome to the fourth North York Moors Chamber Music Festival I would like to express my continuing thanks to all those who – ‘Along the Danube’. Last year’s Russian theme, concentrating are supporting this festival and it gives me great pleasure to watch on the great Russian masters, celebrated some astonishing music it thrive after all the investment, belief and tireless campaigning. particularly from the twentieth century. In Eastern Europe, which It is also growing while remaining true to its principles, something the Danube famously penetrates, we find a similar phenomenon and I feel very strongly about. choosing which music to feature was a challenging process since My aim is to keep ticket prices low so that we don’t price anyone there is so much quality. The musical output from Eastern Europe out; this is a festival for everybody regardless of background or was too monumental to ignore for a theme at some point and us position. This year, after three of keeping the prices unchanged, musicians are thrilled to be championing this exceptional repertoire we were forced to raise them marginally which we hope you especially now we have such a hungry and appreciative audience. understand. We intend to try and keep this price stable for the North YorK Moors chAMBer MUsic FestiVAL Equally, as ever, the spiritual passion contained in the music next three years. Therefore your support is paramount, however shortListeD for a royal PhiLhArMoNic societY itself resonates profoundly within the walls of our extraordinary minimal, as we can no longer necessarily rely on public funding. -

Festival Highlights

FESTIVAL HIGHLIGHTS 2: Terry Waite Photo: Gemma Levine Gemma Levine Photo: Neda Navaee Photo: 1: Harriet Harman 1 2 3 3: Lars Vogt 4 4 Mitchell Paul Marc Photo: 4: Damon Hill THE SPEED OF LIFE 5: Russell Foster 8: Viv Albertine 6: Miranda Sawyer 9: The Choir - Voices of Hope Photo: Photo: Matt Writtle 5 7: Denise Mina 6 Ollie Grove Photo: 7 8 9 Nick Rutter Photo: 10: Battany Hughes 10 Listen on BBC Radio 3 Find all the programmes at bbc.co.uk/freethinking 11: Richard Hawley 12: Emmy the Great 14: George Saunders Photo: Mike Urwin Mike Photo: 11 12 Alex Photo: Lake 13 13: Simon Armitage 14 15 15: Jim Al-Khalili 16 16: Louise Robinson Photo: Webster Photo: Paul Wolfgang Photo: Photo: Chloe Aftel WELCOME FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Welcome to BBC Radio 3’s Free Thinking 4.10pm – 6.30pm 10.15am – 11.15am 2.05pm – 3.10pm 7.45pm – 9.00pm (Saturday) 11.00am – 12.00pm (Sunday) 3.55pm – 4.55pm festival – a packed weekend of debates, NORTHERN ROCK NORTHERN ROCK NORTHERN ROCK NORTHERN ROCK SAGE TWO interviews and live music at Sage Gateshead. FOUNDATION HALL FOUNDATION HALL FOUNDATION HALL FOUNDATION HALL FASTER, FASTER, FASTER? We’re bringing together writers, artists, IN TUNE HOW SHORT IS A NEW GENERATION THINKERS 2017 THE VERB politicians, sportspeople and scientists to SHORT STORY? Can the steady tortoise still beat the rapid hare in Suzy Klein hosts live performances from pianist The New Generation Thinkers is an annual competition Ian Macmillan presents two editions of Radio 3’s today’s world? Anne McElvoy chairs a debate with grapple with ‘The Speed of Life’: how a Lars Vogt with members of Royal Northern Sinfonia, Acclaimed American short story writer George run by BBC Radio 3 and the Arts and Humanities poetry and spoken word programme. -

The Avison Ensemble Young Musicians’ Awards 2016

The Avison Ensemble Young Musicians’ Awards 2016 Young musicians and singers are invited to take part in the annual music awards sponsored by The Avison Ensemble Entrants must be 18 or under on 14th February 2016. Entrants to all categories will be asked to perform two contrasting pieces, one of which must have been written before 1800, on any instrument or voice. There are four categories available to entrants, each category having its own Award, as follows: Category A (Grades 1, 2 & 3 or equivalent) Category B (Grades 4, 5 & 6 or equivalent) Category C (Grade 7 or equivalent and above) Category D (Small classical music groups – Chamber ensembles with no more than 8 players) The panel of artistic assessors will include John Treherne MBE (until recently Head of Gateshead Schools’ Music Service), Poppy Holden (soprano, voice coach, formerly Head of Vocal Studies, Newcastle University), Deborah Thorne (Avison Ensemble and ex-Northern Sinfornia cellist), and Gordon Dixon (Executive Director of The Avison Ensemble). Other appropriate assessors may be co-opted as required. HOW TO APPLY Details and an application form can be found on our website at www.avisonensemble.com DEADLINE FOR APPLICATIONS: Monday 4th January 2016 FIRST ROUND ASSESSMENT First round assessments will be take place at Open Performance Workshops in The Literary and Philosophical Society, 23 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 1SE on the following days: Monday 18th, Thursday 21st and Friday 22nd January 2016 from 4pm to 7pm, and Saturday 23rd January from 10am to midday. Individuals will be sent their own appointment times. During the course of the workshop entrants: o will be asked to play their two contrasting pieces and encouraged to introduce them; o will receive a verbal assessment. -

Avisonensemble.Com Reviews Charles Avison 12 Concertos Opus 6

reviews Charles Avison 12 Concertos Opus 6 The Avison Ensemble Pavlo Beznosiuk (director & violin) 2 CDs on Naxos, Naxos 8.557553-54 … bounce with vim and vigour … the playing is full of character and charm … heartfelt performances of these pieces The Penguin Guide to Classical Music January 2009 Avison’s ability to pattern his works on the music of others stood him in good stead throughout his career…His concertos are skillfully fashioned, have plenty of vitality and show perceptive use of dynamic contrast…Played as vibrantly and freshly as it is here, on period instruments by this expert ensemble from Avison’s own city, and led by the excellent violinist Pavlo Beznosiuk, one cannot help but respond to the vitality of the writing… BBC Music Magazine Nicholas Anderson This is an important release for all lovers of 18th-century English music, since it is the first time that Charles Avison’s complete set of 12 string concertos, Op.6, has been recorded. Hitherto, only his 12 concertos drawing upon harpsichord sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti have found much favour with record companies, though Emanuel Hurwitz and his ensemble recorded six concertos from Avison’s Op.6 for L’Oiseau-Lyre back in 1970. Newcastle-born Avison was a contemporary of Arne, Boyce and Stanley and a prolific composer of concertos of which some 50 or so were published during his lifetime. Like his teacher, Geminiani, Avison preferred a four-part concertino group consisting of two violins, viola and cello, rather than the more usual trio of two violins and cello favoured by Corelli and Handel. -

Avisonscarlatti Reviews

reviews Charles Avison Concerti Grossi after Scarlatti The Avison Ensemble Pavlo Beznosiuk, director & violin 2 CDs on Divine Arts, dda 21213 • BBC Radio 3 Essential CD of the Week, 7 - 11 November 2011 … this is exemplary baroque string playing … each concerto is a joy to listen to … the playing is uniformly superb throughout Classic FM Magazine Malcolm Hayes In the unlikely surroundings of 18 th century Newcastle, local musical entrepreneur Charles Avison made a name for himself with his Baroque string concertos, including this collection based on existing works (some of them now lost) by Italy's Domenico Scarlatti. While rather short-changing the fiery vibrancy of Scarlatti's brilliant harpsichord writing, Avison's arrangements and re-workings are never less than engaging and stylish. However, the real trump card is the quality with which they're played here. Under leader-director Pavlo Beznosiuk, springy rhythms combine with a lovely pliable way with the music's pacing and phrasing. ClassicalNet Gerald Fenech This delightful two disc set is a welcome addition to the catalogue where these concertos have been sparsely represented of late. After having tackled similar works for Divine Art, the Avison Ensemble now lend their talented vein to these Scarlatti arrangements by their namesake composer and the result is quite enthralling. avisonensemble.com 1 Each concerto is a joy to listen to and although the music is brought together from other works, there is an innate feel that everything is complete and should be "there". Pavlo Beznosiuk directs these works with consummate panache and his violin playing is also impeccable as can be expected from this old warhorse of this sort of repertoire. -

YMA 2013 Entry Form

The Avison Ensemble Young Musicians’ Awards 2013 Young musicians and singers are invited to take part in this annual music award sponsored by The Avison Ensemble Students under 18 are invited to perform two pieces of music, one of which must be by an 18th Century composer of their choice, on any instrument or voice. Performers should provide their own accompanist (if required). A harpsichord is available if required. There are four categories available to entrants, each category having its own prize for the winning entrant. Entrants to all categories will be asked to perform two contrasting pieces (maximum 6 minutes overall) and music grades will be formed into the following categories: Category A (Grades 1, 2 & 3 or equivalent) Category B (Grades 4, 5 & 6 or equivalent) Category C (Grade 7 or equivalent and above) Category D (Small classical music groups – Chamber ensembles with no more than 8 players) The assessors will be John Treherne MBE (Head of Gateshead Schools’ Music Service), Gordon Dixon (Executive Director of The Avison Ensemble) and Deborah Thorne (Ensemble player). We hope to offer all entrants the opportunity of master classes and advice from distinguished international musicians at various stages of the competition. HOW TO APPLY Details and an application form can be found on our website at www.avisonensemble.com DEADLINE FOR APPLICATIONS: by post or email – Friday 30th November 2012 FIRST ROUND ASSESSMENT First round assessments will be take place at Open Performance Workshops on Friday 25th and Sunday 27th January 2013 from 10am to 5pm in the William Shield Room, Dryden Centre, Evistones Road, Low Fell, Gateshead, NE9 5UR. -

Avisonensemble.Com Reviews Charles Avison Concerti Grossi After

reviews Charles Avison Concerti Grossi after Geminiani The Avison Ensemble Pavlo Beznosiuk (director & violin) 2 CDs on Divine Arts, dda 21210 … brisk and lively performances … one of the finest baroque ensembles now in existence … an exceptional issue in every way Early Music News Richard Maunder Avison's recently rediscovered arrangements as seven-part concertos of Geminiani's Op. 1 violin sonatas continue an honourable tradition dating back to Geminiani's own arrangements of Corelli's Op. 5 sonatas. They make very convincing concertos and are a welcome addition to the repertoire (Avison omitted Geminiani's Op. 1 No. 11, but Beznosiuk has skilfully remedied the deficiency). This is music of outstanding quality and originality: Geminiani has the rare ability to do the unexpected while making the result sound completely natural, and Avison's ingenious and technically assured versions do much to enhance the appeal of these pieces. The performances are outstanding. The band (strings 3/3/2/2/1 plus harpsichord) is richly sonorous; the ensemble is faultless; the tempi are seemingly infallibly judged; the phrasing is subtle and expressive; and virtuoso solos are dispatched with aplomb. What more could one possibly want? It's a real pleasure to have two absolute winners from The Avison Ensemble to review in the same issue. They must surely be one of the finest baroque ensembles now in existence. avisonensemble.com 1 The Daily Telegraph Elizabeth Roche These discs throw fascinating light on the 18th-century English musical public's insatiable appetite for Italian concerti grossi. Avison's recently discovered transcriptions of 12 solo violin sonatas by one of London's most popular expatriate Italian musicians were perfectly calculated to satisfy this demand. -

Avisonensemble.Com Reviews Charles Avison Sonatas for Harpsichord

reviews Charles Avison Sonatas for Harpsichord Opus Op. 5 and 7 The Avison Ensemble Gary Cooper (harpsichord), Pavlo Beznosiuk and Caroline Balding (violins), Robin Michael (cello) 2 CDs on Divine Arts, dda 21215 • MusicWeb recording of the month November 2010 • Final release in the Avison Ensemble's complete recording of Avison's orchestral and chamber music … superbly crafted melodic gems … performances notable for their wit, elegance and refinement … a very welcome and refreshing release International Record Review Marc Rochester The 12 sonatas on this disc are something of a hybrid between the Trio Sonata and the accompanied Keyboard Sonata. In his excellent notes, Simon Fleming suggests that the model for this type of sonata comes from Rameau, but he adds ‘Avison created a new species of sonata that was largely peculiar to the North East'. More than that, we are told that this type of sonata was a ‘popular genre in the north east'. I wonder if those who inhabit the north east of England today are aware that, in the eighteenth century, their forebears, were fans of such elevated music; and I can't help wondering what might have now supplanted the harpsichord sonata in the life of present-day Tynesiders. Enough of idle speculation. The booklet also tells us Charles Avison was a ‘little known Newcastle born composer'; something which came as a surprise to me since my childhood seemed to be surrounded by Avison's music. My father, himself avisonensemble.com 1 having spent some of his formative years in the north east, possessed several copies of pieces by Avison, which he played with great enthusiasm; it was one of these that he gave me to learn at my first organ lesson with him. -

Community Foundation Serving Tyne Wear and Northumberland Grants Awarded 1 April 2015 - 31 March 2016 Amount Awarded £7,294,306.61 Number of Grants 1417

Community Foundation serving Tyne Wear and Northumberland Grants Awarded 1 April 2015 - 31 March 2016 Amount Awarded £7,294,306.61 Number of grants 1417 Grantee Program name Granted Fourteen Fund Back on the Map Towards community capacity building 22,000.00 Young Asian Voices Towards YAV sports academy - year 1 5,000.00 Heritage Coast Partnership Towards reconnecting coast and community 15,000.00 Sans Street Youth & Community Centre Towards Positive Impact Project East (PIPE) 20,000.00 Back on the Map Towards volunteer capacity building programme - year 1 6,250.00 Ryhope Community Association Towards Connecting Communities - year 1 8,560.00 Blue Watch Youth Centre Towards community social action and volunteering 13,008.00 B Active N B Fit CIC Towards social retreat project 15,000.00 Back on the Map Towards community capacity building 22,000.00 Hendon Young People's Project Towards We'ar Safe, fishing, cooking, positive, active and happy project 14,720.00 Total for Fourteen Fund 10 grants 141,538.00 Abbot Memorial Fund Individual Towards new beds 30.00 Individual Towards decorating materials 100.00 Individual Towards furniture 100.00 Individual Towards bed and carpets 50.00 Individual Towards beds 100.00 Individual Towards carpets 100.00 Individual Towards bedding and storage 100.00 Individual Towards vacuum cleaner and bedding 20.00 Individual Towards carpets and soft furnishings 100.00 Individual Towards carpets 100.00 Individual Towards storage 100.00 Individual Towards carpets 100.00 Individual Towards household items 100.00 Individual -

Cherryburn Times EASTER 05 V3

VOLUME 4 NUMBER 7 EASTER 2005 The Newsletter of The Bewick Society Photograph by courtesy of Anderson and Garland A NEW P ORTRAIT OF TH OMAS B EWICK We celebrate our first issue in colour with this newly discovered portrait by an unknown artist. It is a copy of the well known Ramsay portrait, which we reproduce on the back page with the story of the discovery. to Iain Bain for pointing out to me that Nigel A Bewick Grail? Tattersfield’s Bookplates (1999, p.161) reveals the image as By David Gardner-Medwin the bookplate engraved in 1822 for Miss Barbara Liddell of Dockwray Square, North Shields. In it, Newcastle is For two years or more I have been questing for a Bewick represented by the castle keep, the spire of St Nicholas, grail – an illustration of his cottage on the Forth. He lived the town wall – and a single cottage of two gables, placed there with his family for 30 very happy years and it seems on the Forth, just where the cot ought to be. unlikely that he never drew or engraved it when so many of his vignettes and other engravings show cottages that at least approximate to his childhood home at Cherryburn. We can spot Cherryburn in these images because we know what it actually looked like from annotated drawings, such as John Bewick’s of 1781, and of course from early photographs as well as the present appearance of the building. The cot on the Forth was demolished in the 1840s. Surely someone must have recorded it? When the medieval town of Newcastle and its 13th century walls were largely demolished in the 1830s-50s, there were those who protested or sadly busied themselves with recording what was to be lost.