RBS Response to Issues Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Banking Service Quality - Great Britain

Business banking service quality - Great Britain Independent service quality survey results Business current accounts Published August 2019 As part of a regulatory requirement, an independent survey was conducted to ask customers of the 14 largest business current account providers if they would recommend their provider to other small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs*). The results represent the view of customers who took part in the survey. These results are from an independent survey carried out between July 2018 and June 2019 by BVA BDRC as part of a regulatory requirement, and we have published this information at the request of the providers and the Competition and Markets Authority so you can compare the quality of service from business current account providers. In providing this information, we are not giving you any advice or making any recommendation to you. SME customers with business current accounts were asked how likely they would be to recommend their provider, their provider’s online and mobile banking services, services in branches and business centres, SME overdraft and loan services and relationship/account management services to other SMEs. The results show the proportion of customers of each provider who said they were ’extremely likely’ or ‘very likely’ to recommend each service. Participating providers: Allied Irish Bank (GB), Bank of Scotland, Barclays, Clydesdale Bank, Handelsbanken, HSBC UK, Lloyds Bank, Metro Bank, NatWest, Royal Bank of Scotland, Santander UK, The Co-operative Bank, TSB, Yorkshire Bank. Approximately 1,200 customers a year are surveyed across Great Britain for each provider; results are only published where at least 100 customers have provided an eligible score for that service in the survey period. -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Pie File No

UNITED STATES SECURITI ES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 DIVISION OF TRADING AND MARKETS August 3, 20 15 Ms. Connie Milonakis Davis Polk & Wardwell London LLP 5 Aldermanbury Square London EC2V 7HR England Re: The Royal Bank of Scotland Group pie File No. TP 15-17 Dear Ms. Milonakis: In your letter dated August 3, 2015, as supplemented by conversations with the staff, you request on behalf ofThe Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc, a public limited company organized under the laws of the United Kingdom and registered in Scotland ("RBSG"), an exemption from Rule 102 of Regulation Munder the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended ("Exchange Act") in connection with the distribution of the ordinary shares of RBSG ("RBSG Shares") and the American Depositary Shares each representing the right to receive two RBSG Shares ("RBSG ADSs") by way of a placement of RBSG Shares (the "Placing") to interested purchasers by United Kingdom Financial Investments, which manages the shareholding of the United Kingdom Treasury in RBSG. 1 You seek an exemption to permit RBSG and RBSG Affiliates to conduct specified transactions outside the United States in RBSG Ordinary Shares during the Placing. Specifically, you request that: (i) RBSG CIB be permitted to continue to engage in derivatives and investor product market-making and hedging activities as described in your letter; (ii) the RBSG Asset Manager and RBSG Investment Managers be permitted to continue to engage in investment management activities as described in your letter; (iii) the RBSG Trustees and Personal Representatives be permitted to continue to engage in trustee and personal representative-related activities as described in your letter; (iv) the RBSG Banking Units be permitted to continue to engage in banking-related activities as described in your letter; and (v) the RBSG Stock Borrowing and Lending Units be permitted to continue to engage in stock borrowing and lending activities as described in your letter. -

Bank of Scotland

Bank of Scotland plc (Incorporated with limited liability in Scotland with registered number SC 327000) €60 billion Covered Bond Programme unconditionally guaranteed by HBOS plc (incorporated with limited liability in Scotland with registered number SC218813) and unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed as to payments of interest and principal by HBOS Covered Bonds LLP (a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales) Under this €60 billion covered bond programme (the “Programme”), Bank of Scotland plc (the “Issuer”) may from time to time issue bonds (the “Covered Bonds”) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer(s) (as defined below). The payments of all amounts due in respect of the Covered Bonds have been unconditionally guaranteed by HBOS plc (“HBOS” in its capacity as guarantor, the “HBOS Group Guarantor”). HBOS Covered Bonds LLP (the “LLP” and, together with the HBOS Group Guarantor, the “Guarantors”) has guaranteed payments of interest and principal under the Covered Bonds pursuant to a guarantee which is secured over the Portfolio (as defined below) and its other assets. Recourse against the LLP under its guarantee is limited to the Portfolio and such assets. The Covered Bonds may be issued in bearer or registered form (respectively “Bearer Covered Bonds” and “Registered Covered Bonds”). The maximum aggregate nominal amount of all Covered Bonds from time to time outstanding under the Programme will not exceed €60 billion (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Programme Agreement described herein), subject to increase as described herein. The Covered Bonds may be issued on a continuing basis to one or more of the Dealers specified under General Description of the Programme and any additional Dealer appointed under the Programme from time to time by the Issuer (each a “Dealer” and together the “Dealers”), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis. -

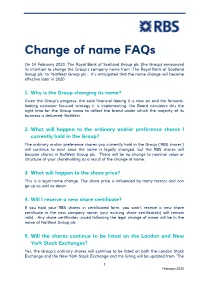

Change of Name Faqs

Change of name FAQs On 14 February 2020, The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (the Group) announced its intention to change the Group’s company name from ‘The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc’ to ‘NatWest Group plc’. It’s anticipated that the name change will become effective later in 2020. 1. Why is the Group changing its name? Given the Group’s progress, the solid financial footing it is now on and the forward- looking customer focused strategy it is implementing, the Board considers this the right time for the Group name to reflect the brand under which the majority of its business is delivered: NatWest. 2. What will happen to the ordinary and/or preference shares I currently hold in the Group? The ordinary and/or preference shares you currently hold in the Group (‘RBS shares’) will continue to exist once the name is legally changed, but the RBS shares will become shares in NatWest Group plc. There will be no change to nominal value or structure of your shareholding as a result of the change of name. 3. What will happen to the share price? This is a legal name change. The share price is influenced by many factors and can go up as well as down. 4. Will I receive a new share certificate? If you hold your RBS shares in certificated form, you won’t receive a new share certificate in the new company name; your existing share certificate(s) will remain valid. Any share certificates issued following the legal change of name will be in the name of NatWest Group plc. -

Bank of England List of Banks- October 2020

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 1st October 2020 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 31st August 2020 can be found below) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The Distribution Finance Capital Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC AIB Group (UK) Plc EFG Private Bank Limited Al Rayan Bank PLC Europe Arab Bank plc Aldermore Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited (Applied to Cancel) FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Allica Bank Ltd FCE Bank Plc Alpha Bank London Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Atom Bank PLC Gatehouse Bank Plc Axis Bank UK Limited Ghana International Bank Plc GH Bank Limited Bank and Clients PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Bank Leumi (UK) plc Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Hampden & Co Plc Bank of China (UK) Ltd Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc Handelsbanken PLC Bank of London and The Middle East plc Havin Bank Ltd Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Scotland plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank Saderat Plc HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank Sepah International Plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC ICBC (London) plc BFC Bank Limited ICBC Standard Bank Plc Bira Bank Limited ICICI Bank UK Plc BMCE Bank International plc Investec Bank PLC British Arab Commercial Bank Plc Itau BBA International PLC Brown Shipley & Co Limited JN Bank UK Ltd C Hoare & Co J.P. -

Natwest Group United Kingdom

NatWest Group United Kingdom Active This profile is actively maintained Send feedback on this profile Created before Nov 2016 Last update: Feb 23 2021 About NatWest Group NatWest Group, founded in 1727, is a British banking and insurance holding company based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Its main subsidiary companies are The Royal Bank of Scotland, NatWest, Ulster Bank and Coutts. Prior to a name-change in July 2020, it was known as Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Group. After a massive bailout in 2008, a majority of RBS' shares were purchased by the UK Government. In 2014 the bank embarked on a restructuring process that saw it refocus on its business in the UK and Ireland. As part of this process it divested its ownership of Citizens Financial Group, the 13th largest bank in the United States, in 2015. As of 2020 it remains 61.93% UK Government owned, via UK Financial Investments (UKFI). Website https://www.natwestgroup.com/ Headquarters 36 St Andrew Square EH2 2YB Edinburgh Scotland United Kingdom CEO/chair Alison Rose CEO Supervisor Bank of England Annual report Annual report 2020 Ownership listed on London Stock Exchange Natwest Group is majority-owned by the UK government since 2008, which currently holds 61.93 % of the shares. Complaints NatWest Group does not operate a complaints channel for individuals and communities that may be adversely affected by and its finance. However, the bank can be contacted via the contact form here (e.g. using ‘General Service’ as account type). grievances Stakeholders may raise complaints via the OECD National Contact Points (see OECD Watch guidance). -

2020-Bos-Annual-Report.Pdf

Bank of Scotland plc Report and Accounts 2020 Member of Lloyds Banking Group Bank of Scotland plc Contents Strategic report 2 Directors’ report 10 Directors 14 Forward looking statements 15 Independent auditors’ report 16 Consolidated income statement 25 Statements of comprehensive income 26 Balance sheets 28 Statements of changes in equity 30 Cash flow statements 32 Notes to the accounts 33 Subsidiaries and related undertakings 122 Registered office: The Mound, Edinburgh EH1 1YZ. Registered in Scotland No. 327000 Bank of Scotland plc Strategic report Principal activities Bank of Scotland plc (the Bank) and its subsidiaries (together, the Group) provide a wide range of banking and financial services. The Group’s revenue is earned through interest and fees on a broad range of financial services products including current and savings accounts, personal loans, credit cards and mortgages within the retail market; loans and other products to commercial, corporate and asset finance customers; and private banking. Business review In the year to 31 December 2020, the Group recorded a profit before tax of £883 million compared to £1,278 million in the year to 31 December 2019. Total income decreased by £886 million, or 15 per cent, to £5,147 million in the year ended 31 December 2020 compared to £6,033 million in 2019 with a £220 million decrease in net interest income combined with a reduction of £666 million in other income. Net interest income was £5,208 million in the year ended 31 December 2020, a decrease of £220 million, or 4 per cent compared to £5,428 million in 2019 reflecting the lower rate environment, actions taken during the year to support customers and reduced levels of customer activity and demand during the coronavirus pandemic. -

Ross, D.M. (2002) 'Penny Banks' in Glasgow, 1850-1914

Ross, D.M. (2002) 'Penny banks' in Glasgow, 1850-1914. Financial History Review, 9 (1). pp. 21-39. ISSN 0968-5650 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/6739/ Deposited on: 27 August 2009 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Financial History Review 9 (2002), pp. 21–39 Printed in the United Kingdom © 2002 Cambridge University Press. ‘Penny banks’ in Glasgow, 1850–19141 DUNCAN M. ROSS University of Glasgow When William Callender of Royal Bank of Scotland’s Glasgow office died in May 1868, there was found, folded in the pocket of his greatcoat, a handwritten list of those ‘penny banks’ that he had played a significant role helping to create.2 It begins with Barony Penny Bank, opened on 15 May 1852, and concludes with Working Men’s Provident Bank in Partick, that commenced on 18 March 1865. Over the intervening period, Callender had been involved in the promotion of 23 others, including some located far from Glasgow, such as at Broughty Ferry, Dundee; Padiham, Yorkshire; and Greenwich, Kent. That Callender contributed so much to the ‘penny bank’ movement and appeared to value these institutions so highly that he carried this note about with him at all times supports the Glasgow Herald’s 1860 description of his relationship to ‘penny banks’ as one of ‘the first who made the principle a living fact’.3 It also reveals something of the commitment of bank officers working in other institutions to the ‘penny bank’ cause. This was very much part of the middle-class and philanthropic attitude that sustained ‘penny banks’ and saw them develop as one of the most remarkable social phenomena of the nineteenth century. -

The Sustainability Challenge

1 The sustainability challenge Opportunities and risks for UK businesses 2 Time for change Globally, sustainability is now part of the fabric of business strategy for organisations of all sizes, and UK companies are leading the way. The UK has successfully cut carbon emissions faster than any other G7 nation1, with business delivering a major part of that progress. This hasn’t been at the expense of profit. The so-called ‘clean economy’ is forecast to grow four times faster than the economy as a whole.2 But transition to sustainable business practices can be challenging without support. Whatever the size of your business, we are committed to helping our clients in their transition to sustainable business models and operations, and to pursue new clean growth opportunities. Wherever you are on your sustainability journey, Find out in this document how businesses are Bank of Scotland can help you make savings adapting and why, and how we can help you and improve your environmental footprint. realise the benefits and manage the risks for a greener and more prosperous future. To find out more about funding and support available from Bank of Scotland, see page 9. 3 What is sustainability in business terms? A sustainable business is one that is resilient, and fully connected to the social and environmental systems around it. For many, this means focusing on the ‘triple bottom line’ of people, The UK has cut carbon emissions by 42% since 1990 while planet and profit – setting targets the economy has grown by 67%4 around this and reporting performance to shareholders, 180 investors and stakeholders. -

Lloyds Bank PLC, Bank of Scotland Plc and the Mortgage Business Plc (Together “The Banks”) a Financial Penalty of £64,046,800 Pursuant to Section 206 of the Act

FINAL NOTICE To: Lloyds Bank PLC, Bank of Scotland plc, and The Mortgage Business Plc Reference Numbers: 119278, 169628 and 304154 Addresses: 25 Gresham Street, London, EC2V 7HN The Mound, Edinburgh, Midlothian, EH1 1YZ Trinity Road, Halifax, West Yorkshire, HX1 2RG Date: 11 June 2020 1. ACTION 1.1. For the reasons given in this Final Notice, the Authority hereby imposes on Lloyds Bank PLC, Bank of Scotland plc and The Mortgage Business Plc (together “the Banks”) a financial penalty of £64,046,800 pursuant to section 206 of the Act. 1.2. The Banks agreed to resolve all issues of fact and liability and qualified for a 30% discount under the Authority’s executive settlement procedures. Were it not for this discount, the Authority would have imposed a financial penalty of £91,495,400 on the Banks. 1 2. SUMMARY OF REASONS 2.1. Between 7 April 2011 and 21 December 2015 (the “Relevant Period”), the Banks breached Principles 3 and 6 of the Authority’s Principles for Businesses in relation to their handling of mortgage customers in payment difficulties or arrears. 2.2. The Banks did not fully rectify failings in their mortgage arrears handling activities during the Relevant Period, despite some of those failings having been identified from as early as April 2011, and despite subsequent identification of issues (in respect of poor customer treatment and inadequate systems and controls) by the Banks’ external consultants and the Authority. As a result, some of the failings continued for over four and a half years. 2.3. The Banks put a large number of customers (including those who were likely to be vulnerable) at risk of being treated unfairly. -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

Pension Trust/Scheme

Your authority to operate account(s) for a Pension Trust/Scheme This Authority is applicable to customers who hold account(s) with Bank of Scotland plc (the “Bank”). This mandate contains your authority to operate the account(s) and will replace any existing mandates in relation to the account(s). It will operate at a customer level ensuring identical signing across all account(s) held in the scheme name and also will apply to any account(s) the scheme may open in the future. This Authority must be signed by: • All trustees; and • Anyone authorised to sign on behalf of a corporate trustee (if applicable); and • Any scheme administrator or scheme practitioner or fund manager (if applicable). To: Bank of Scotland plc (the “Bank”). We, Insert name of individual trustee(s) and Insert name of corporate trustee(s) (the “Corporate Trustee(s)”) (together the “Trustees”) of the Insert full name of the (the “Scheme”) trust (e.g. The Trustees of ABC scheme) 1 The Scheme’s instructions to the Bank The Scheme (“you”) confirms to the Bank (“us”) that: 1.1 Bank of Scotland plc is appointed as your bankers; 1.2 You authorise the Bank to operate your account in accordance with: • the signatories and signing restrictions in Sections 2 and 3 (which replace any existing signatories and signing instructions you may have given before in relation to the Account); • the General Terms and Conditions which have been supplied to you in Section 4 (and which may be varied from time to time); • the relevant terms and conditions for the account(s) and ancillary services