Some Notes on Larkspur Press Publications As Fine Printing J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER 43 Antikvariat Morris · Badhusgatan 16 · 151 73 Södertälje · Sweden [email protected] |

NEWSLETTER 43 antikvariat morris · badhusgatan 16 · 151 73 södertälje · sweden [email protected] | http://www.antikvariatmorris.se/ [dwiggins & goudy] browning, robert: In a Balcony The Blue Sky Press, Chicago. 1902. 72 pages. 8vo. Cloth spine with paper label, title lettered gilt on front board, top edge trimmed others uncut. spine and boards worn. Some upper case letters on title page plus first initial hand coloured. Introduction by Laura Mc Adoo Triggs. Book designs by F. W. Goudy & W. A. Dwiggins. Printed in red & black by by A.G. Langworthy on Van Gelder paper in a limited edition. This is Nr. 166 of 400 copies. Initialazed by Langworthy. One of Dwiggins first book designs together with his teacher Goudy. “Will contributed endpapers and other decorations to In a Balcony , but the title page spread is pure Goudy.” Bruce Kennett p. 20 & 28–29. (Not in Agner, Ransom 19). SEK500 / €49 / £43 / $57 [dwiggins] wells, h. g.: The Time Machine. An invention Random House, New York. 1931. x, 86 pages. 8vo. Illustrated paper boards, black cloth spine stamped in gold. Corners with light wear, book plate inside front cover (Tage la Cour). Text printed in red and black. Set in Monotype Fournier and printed on Hamilton An - dorra paper. Stencil style colour illustrations. Typography, illustra - tions and binding by William Addison Dwiggins. (Agner 31.07, Bruce Kennett pp. 229–31). SEK500 / €49 / £43 / $57 [bodoni] guarini, giovan battista: Pastor Fido Impresso co’ Tipi Bodoniani, Crisopoli [Parma], 1793. (4, first 2 blank), (1)–345, (3 blank) pages. Tall 4to (31 x 22 cm). -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Political Order in Changing Societies

Political Order in Changing Societies by Samuel P. Huntington New Haven and London, Yale University Press Copyright © 1968 by Yale University. Seventh printing, 1973. Designed by John O. C. McCrillis, set in Baskerville type, and printed in the United States of America by The Colonial Press Inc., Clinton, Mass. For Nancy, All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form Timothy, and Nicholas (except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Library of Congress catalog card number: 68-27756 ISBN: 0-300-00584-9 (cloth), 0-300-01171-'7 (paper) Published in Great Britain, Europe, and Africa by Yale University Press, Ltd., London. Distributed in Latin America by Kaiman anti Polon, Inc., New York City; in Australasia and Southeast Asia by John Wiley & Sons Australasia Pty. Ltd., Sidney; in India by UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt., Ltd., Delhi; in Japan by John Weatherhill, Inc., Tokyo. I·-~· I I. Political Order and Political Decay THE POLITICAL GAP The most important political distinction among countries con i cerns not their form of government but their degree of govern ment. The differences between democracy and dictatorship are less i than the differences between those countries whose politics em , bodies consensus, community, legitimacy, organization, effective ness, stability, and those countries whose politics is deficient in these qualities. Communist totalitarian states and Western liberal .states both belong generally in the category of effective rather than debile political systems. The United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union have different forms of government, but in all three systems the government governs. -

Brand Identity Guide 05/18 the Brand Identity Guide Is Designed to Serve As a Resource for All Your Marketing and Communication Needs

Brand Identity Guide 05/18 The Brand Identity Guide is designed to serve as a resource for all your marketing and communication needs. Consult this manual before you begin to develop your marketing and communication projects and when you need guidance in identifying the University’s branding and editorial style. Adherence to the principles and practices contained in this guide simplifies and systemizes procedures for producing your communication projects, as well as helps to strengthen and enhance the image and identity of St. John’s University. Contact your account director in the Office of Marketing and Communications for assistance with developing a strategic communication plan; design and production; copywriting; web development; media buying; and other communication services. Table of Contents Overview of the Brand Identity Platform 2 Getting Started 4 Print Communication 4 Web Communication 6 Media Communication 7 Editorial Guidelines 8 Design Guidelines 20 University Seal 20 University Logo and Usage 21 Typefaces 29 University Colors 30 Stationery 32 University Vision and Mission Statements 34 1 Overview of the Brand Identity Platform BRAND CHAPTERS Academic Excellence Without Bounds Faith, Service, and Success At St. John’s University, we are on a mission—to give Can you do well in life while being a force for good? talented students from all walks of life a personal and You can, and our graduates do. Whatever their profession— professional edge with an outstanding education that doctor, lawyer, CEO, teacher, entrepreneur, or advocate builds on their individual abilities and aspirations. Our for those in need—St. John’s alumni use their time and commitment is evident in the success of our students. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Chiefly Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 316 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are considered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering, and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inventory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

TEX and TUG NEWS

Volume 2, Number 1 February 1993 TEX and TUG NEWS for and by the TEX community A Publication of the TEX Users Group Electronic version TEX and TUG NEWS Mission Statement The TEX Users Group (TUG) provides leadership: 1. to encourage and expand the use of TEX, METAFONT, and related systems 2. to ensure the integrity and portability of TEX, METAFONT, and related systems 3. to foster innovation in high-quality electronic document preparation TEX and TUG NEWS is a newsletter for TEX and LATEX users alike: a forum for exchanging information, tips and suggestions; a regular means of communicating news items to one another; a place where information about TEX and TUG can be quickly disseminated. Throughout the newsletter \TEX" is understood to mean TEX, LATEX, AMS-TEX, and other related programs and macros. TEX and TUG NEWS is produced with the standard LATEX distribution, and is to be as portable a document as possible. The entire contents of this newsletter are being placed in the public domain. The source file of this issue will be placed in the aston, shsu, and stuttgart archives, as well as at the heidelberg, labrea, and ymir archives. Copying and reprinting are encouraged; however, an acknowledgement specifying TEX and TUG NEWS as the source would be appreciated. Submissions to TEX and TUG NEWS should be short, the macros must work, and the files must run without special font or graphics requirements: this is to be a portable newsletter (the new font selection scheme has not yet been imple- mented). Correspondence may be sent via e-mail to [email protected] with the sub- ject line NEWSLETTER. -

The Auchincloss Collection of Fine Printing & Press Books

The Auchincloss Collection of Fine Printing & Press Books Catalogue o ne: a–D SoPhie SChneidemAn RARe BookS item 5 THE KENNETH AUCHINCLOSS COLLECTION OF FINE PRINTING & PRESS BOOKS catalogue one: a–d Including works from the allen, arion, ashendene, Barbarian, Bird & Bull, Bremer, Chamberlain, Colt, Cresset, Curwen & Doves Presses, as well as books illustrated and designed by thomas Bewick and W. a. Dwiggins SOPHIE SCHNEIDEMAN RARE BOOKS london If you are interested in buying or selling rare books, need a valuation or just hon- est advice please contact me at: SCHNEIDEMAN GALLERY open by appointment 7 days a week or by chance – usually Mon–Fri 11–2.30 331 Portobello Road, london W10 5Sa 020 8354 7365 07909 963836 [email protected] www.ssrbooks.com we are proud to be a member of the aba, pbfa & ilab and are pleased to follow their codes of conduct Prices are in sterling and payment to Sophie Schneideman Rare Books by bank transfer, cheque or credit card is due upon receipt. all books are sent on approval and can be returned within 10 days by secure means if they have been wrongly or inadequately described. Postage is charged at cost. eu members, please quote your vat/tva number when ordering. the goods shall legally remain the property of Sophie Schneideman Rare Books until the price has been discharged in full. Images of all the books are available on request and will be on the website 2 weeks after the catalogue has arrived. Set in emerson [designed by Joseph Blumenthal] and Sistina [designed by Hermann Zapf ] types. -

2012, Commencement Issue

I 2012 Livin' Large "Graduation is not the end; it's Sc the beginning." -Orrin Hatch "I am somebody. I am me. I like being me. And I need nobody to make me somebody." - Louis L'Amour "Most people run a race to see who is fastest. I run a race to see who has the most guts." - Steve Prefontaine "Education: That which discloses the wise and disguises from the foolish their lack of understanding." - Ambrose Bierce "As much as the stress of the production takes over your life, there is nothing more satisfying than eight weeks of hard work, intense memortzation, beautiful harmomes, complicated choreography, and lots of smiling faces molding each of us into our characters and producing a spectacular show." -Lois Rood, from The Music Man lass of 2012 Daisy Eleanora Alexander ICommunity Senire 1-2 & 4, Cross Country 2-3, G:vJAD Volunteer 4. Indoor Track 3. l\htth Team 2, Middle School Tutoring 3, Prom Committee 3, Student Council 1-3, Student Council President 1-3 "Life is mostly froth and bubble, hut hrn things stand like stone, kindness in others, trouble and courage in )Our m, n." --Princess Diana "So you treat )our lme like a lireny, like it only gl·ts to shine for a little "hilc, catch ii in a mason jar,, ith holes in the top and run likl- hell to shm, it off." --Mirancht Lambert Daisy, \\C arc both amazed at e,crything you haw done, and hm, you hmc done it. these past 18 )Cars. Thanks for taking us along on your mnazing journey. -

Electronic 2000 Magazine

AaBbCcDdEeFfGgHhliJjKkL1MmNnOo Pp I RrSsTtUuVvWwXxYyZz12345678908dECE$$0£.%!?00 UPPER AND LOWER CASE. THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TYPE AND. GRAPHIC DESIGN WINTER 1992. $5.00 U.S. $9.90 AUD Age The Electronic 2000 Magazine THE ALPHABET ACCORDING TO PRECISION TYPE ET A is• ff or AARDVARK4,frn,m,,o,,„Bureau / I' 0 ThEFEIS HOKE DEED % B is for Boy t m r y ra The Complete Font Software Resourte 10',1 -71%i-- Reference Guide C is for Columbus Version 0 56.95 4;07c'rc i D is for Bill's,,Trations ""'"Pe from U Design Type found ,/ ■tita An thin E is for [111 at A F is for Flyer '\ Gis for Game Pi JA A H is for llotElllodErn( from Treacyfaces GuitELIKE It I is for 117LstroEt om inotyp THE PRECISION TYPE REFERENCE GUIDE VERSION 4.0 J is for JUNIPER N trom Adobe 0 K is for Ir5 r f P T-Lfrom ,,,,E,,,,,,e,‘ AMAZING! INUEDIBLE! L is for 1.4 no;i It's one of the largest and most . /10 togEs of fonts, 1p H, H A informative font resources ever M is for SBI Ivoun IFIF published! Thousands of fonts Nis for Normande from the Major Type Libraries hem 13,tstrearn (11-11011s, SoftworE Ois for Oz Brush plus Designer foundries and from A', Alphabets Inc Specialty (ollections. P is for Pelican The Precision Type Reference Tools 0 much more., ()is for 1). F TIIMA Guide also features (D-ROM Isom Fetraset Type Libraries, font Software R is for Meg [Hp yts Np Applications & Tools, font (4,'S All for onlg SOU (11111', Products for HP Printers, S is for 9 THE $6.95 COST OF THE REFERENCE GUIDE IS 5(01,0,r_ rye Typographic Reference Books FULLY REFUNDED WITH YOUR FIRST ORDER FROM PRECISION TYPE. -

Fine Press 1

1 Fine Press 1. IN VENICE. The case against Ruskin, and the events leading to Whistler’s tour of Venice in 1880. Parry Sound, Ontario: Church Street Press, 2007, folio, quarter leather, handmade paper-covered boards, linen slip case. not paginated (32 pages). Limited to 15 copies. Printed and illustrated by Alan Stein, who signed on the colophon. This is an account of approximately one year in the life of J.M. Whistler. It follows the libel case of “Whistler vs. Ruskin” with excerpts from the trial, his subsequent bankruptcy, his commission from the Fine Arts Society for a series of twenty-five plates of Venice, letters, and various accounts of his time there during the winter of 1879-80, followed by accounts of the exhibitions at the Grosvenor gallery when he returned. The lithographs are based on Steins on- site sketches made in the same locations as some of Whistler’s on-site pastels and copper-plate engravings. Half-title page wood engraving printed in Venetian Red. Endpapers are full dimension linocut printed on Venetian Red Kurotani Japanese paper. Laid-in is a tall, narrow broadside prospectus, a gallery card for a show featuring Steins work in 2003, a single sheet New Years greeting for 2008, and a card showing the same image as the New Years greeting. No. 100298 -- Price $ 975.00 2. SQUARINGS 3.(Leaf Book) THOMAS By Seamus Heaney SHORT AND THE FIRST BOOK Francisco: Arion PRINTED IN CONNECTICUT Press, 2003, square 4to., pictorial cloth, By Foster M. Johnson cloth-covered slipcase. Meriden, CT: Bayberry Hill Press, 1958, 12mo., full not paginated. -

Richland County Business Service Center Open Businesses with Issued 2018 Richland County Business Licenses As of December 27, 2018 S.C

BSC Open Businesses with Issued 2018 Richland County Business LIcenses 12/27/2018 Richland County Business Service Center Open Businesses with Issued 2018 Richland County Business Licenses As of December 27, 2018 S.C. law provides that it is a crime to knowingly obtain or use personal information from a public body for commercial solicitation. Business Name Doing Business As Business Description (with NAICS code) Physical Location "A" Game Sports and Fitness 611620 -Sports and Recreation Instruction 508 Cartgate Cir Blythewood "Bundles" of Joy 448150 -Clothing Accessories Stores 1971 Lake Carolina Dr Columbia "Lady G" Creations, LLC 314999 -All Other Miscellaneous Textile Product Mills 1061 Sparkleberry Ln Ext Columbia "So" Fresh "So" Clean Janitorial Service 561720 -Janitorial Services 600 Crane Church Rd Columbia "The Barbershop" 812111 -Barber Shops 9400 Two Notch Rd Columbia "The Handy Duck", LLC 236118-B -Residential Remodelers 9519 Farrow Rd Columbia #1 A LifeSafer of South Carolina, Inc LifeSafer 811198 -All Other Automotive Repair and Maintenance 136 McLeod Rd Columbia #1 Lawn Care Service 561730 -Landscaping Services 966 Farnsworth Dr Hopkins #MrGrindOut LLC 624110 -Child and Youth Services 536 Wilkinson Ln Columbia 1 800 Got Junk 562111 -Solid Waste Collection 3405 Margrave Rd Columbia 1 Man Outfit & Helpers 236118-B -Residential Remodelers 324 Cooper Rd Blythewood 100 Gateway SC 531120 -Lessors of Nonresidential Buildings (except Miniwarehouses)100 Gateway Corporate Blvd Columbia 1009 Pine, LLC Sun Massage Therapy 621399 -Offices -

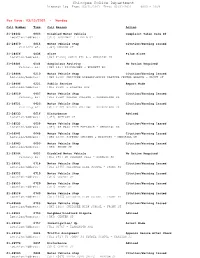

03-15-2021 Through 03-21-2021

Chicopee Police Department Dispatch Log From: 03/15/2021 Thru: 03/21/2021 0000 - 2359 For Date: 03/15/2021 - Monday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 21-28442 0003 Disabled Motor Vehicle Complaint Taken Care Of Location/Address: [CHI] BROADWAY + E MAIN ST 21-28450 0016 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Vicinity of: [CHI] MEADOW ST 21-28456 0036 Alarm False Alarm Location/Address: [CHI F1393] CHICK FIL A - MEMORIAL DR 21-28481 0144 Suspicious Activity No Action Required Vicinity of: [CHI 105] LIQUORSHED - BURNETT RD 21-28488 0210 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 1160] CHICOPEE LIBRARY-EMILY PARTYKA CENTER BRANCH - FRONT ST 21-28496 0221 Public Service Report Made Location/Address: [CHI 2119] - POLASKI AVE 21-28519 0407 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Vicinity of: [CHI F122] SALTER COLLEGE - SHAWINIGAN DR 21-28521 0423 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Vicinity of: [CHI F122] SALTER COLLEGE - SHAWINIGAN DR 21-28533 0616 Disturbance Advised Location/Address: [CHI] ARTISAN ST 21-28535 0626 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] AT MASS PIKE ENTRANCE - MEMORIAL DR 21-28541 0648 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 1338] POPEYES CHICKEN & BISCUITS - MEMORIAL DR 21-28543 0650 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] FRONT ST 21-28544 0655 Disabled Motor Vehicle No Action Required Vicinity of: [CHI F80] DR DEEGANS DELI - BURNETT RD 21-28551 0718 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: