UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1989 Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848 Leopold G. Glueckert Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Glueckert, Leopold G., "Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848" (1989). Dissertations. 2639. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert BETWEEN TWO AMNESTIES: FORMER POLITICAL PRISONERS AND EXILES IN THE ROMAN REVOLUTION OF 1848 by Leopold G. Glueckert, O.Carm. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert 1989 © All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any paper which has been under way for so long, many people have shared in this work and deserve thanks. Above all, I would like to thank my director, Dr. Anthony Cardoza, and the members of my committee, Dr. Walter Gray and Fr. Richard Costigan. Their patience and encourage ment have been every bit as important to me as their good advice and professionalism. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Statistical Bulletin 20 17 1 - Quarter Quarter 1

quarter 1 - 2017 Statistical Bulletin quarter 1 Statistical Bulletin Statistical publications and distribution options Statistical publications and distribution options The Bank of Italy publishes a quarterly statistical bulletin and a series of reports (most of which are monthly). The statistical information is available on the Bank’s website (www.bancaditalia.it, in the Statistical section) in pdf format and in the BDS on-line. The pdf version of the Bulletin is static in the sense that it contains the information available at the time of publication; by contrast the on-line edition is dynamic in the sense that with each update the published data are revised on the basis of any amendments received in the meantime. On the Internet the information is available in both Italian and English. Further details can be found on the Internet in the Statistics section referred to above. Requests for clarifications concerning data contained in this publication can be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. The source must be cited in any use or dissemination of the information contained in the publications. The Bank of Italy is not responsible for any errors of interpretation of mistaken conclusions drawn on the basis of the information published. Director: GRAZIA MARCHESE For the electronic version: registration with the Court of Rome No. 23, 25 January 2008 ISSN 2281-4671 (on line) Notice to readers Notice to readers I.The appendix contains methodological notes with general information on the statistical data and the sources form which they are drawn. More specific notes regarding individual tables are given at the foot of the tables themselves. -

ARTS & HUMANITIES CITATION INDEX JOURNAL LIST Total

ARTS & HUMANITIES CITATION INDEX JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 1151 1. A + U-ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM Monthly ISSN: 0389-9160 A & U PUBL CO LTD, 30-8 YUSHIMA 2-CHOME BUNKYO-KU, TOKYO, JAPAN, 113 2. AAA-ARBEITEN AUS ANGLISTIK UND AMERIKANISTIK Semiannual ISSN: 0171-5410 GUNTER NARR VERLAG, DISCHINGERWEG 5, TUBINGEN, GERMANY, D 72070 3. ACADIENSIS Semiannual ISSN: 0044-5851 UNIV NEW BRUNSWICK, DEPT HISTORY, FREDERICTON, CANADA, NB, E3B 5A3 4. ACTA MOZARTIANA Quarterly ISSN: 0001-6233 DEUTSCHE MOZART-GESELLSCHAFT, FRAUENTORSTRASSE 30, AUGSBURG, GERMANY, D-86152 5. ACTA MUSICOLOGICA Semiannual ISSN: 0001-6241 INT MUSICOLOGICAL SOC, BOX 561, BASEL, SWITZERLAND, CH-4001 6. ACTA POLONIAE HISTORICA Semiannual ISSN: 0001-6829 INST HIST PAN, RYNEK STAREGO MIASTA 29-31, WARSAW, POLAND, 00272 7. ADALYA Annual ISSN: 1301-2746 SUNA & INAN KIRAC RESEARCH INSTITUTE MEDITERRANEAN CIVILIZATIONS, BARBAROS MAH. KOCATEPE SK. NO. 25, KALEICI, TURKEY, ANTALYA, 07100 8. AEVUM-RASSEGNA DI SCIENZE STORICHE LINGUISTICHE E FILOLOGICHE Tri-annual ISSN: 0001-9593 VITA PENSIERO, LARGO A GEMELLI 1, MILAN, ITALY, 20123 9. AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW Quarterly ISSN: 1062-4783 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW, DEPT ENGLISH, INDIANA STATE UNIV, TERRE HAUTE, USA, IN, 47809 10. AFRICAN ARTS Quarterly ISSN: 0001-9933 M I T PRESS, 238 MAIN STREET, STE 500, CAMBRIDGE, USA, MA, 02142- 1046 11. AFRICAN ECONOMIC HISTORY Annual ISSN: 0145-2258 UNIV WISCONSIN MADISON, AFRICAN STUDIES PROGRAM, 205 INGRAHAM HALL, 1155 OBSERVATORY DR, MADISON, USA, WI, 53706 12. AGENDA Quarterly ISSN: 0002-0796 AGENDA, 5 CRANBOURNE COURT ALBERT BRIDGE RD, LONDON, ENGLAND, SW11 4PE 13. AGRICULTURAL HISTORY Quarterly ISSN: 0002-1482 UNIV CALIFORNIA PRESS, C/O JOURNALS DIVISION, 2000 CENTER ST, STE 303, BERKELEY, USA, CA, 94704-1223 14. -

Events, Places and Experiences for Your Holiday 2019 2021 REGIONAL PARK

Events, places and experiences for your holiday 2019 2021 REGIONAL PARK INTER-REGIONAL NATURAL PARK NATIONAL NATURAL RESERVE ARCHAEOLOGY PARK places, experiences, events for your holiday in Marche Legend Adventure and Archaeology park Blue Flag entertainment park The most beautiful Spa Skiing facilities villages in Italy with wellness centres Orange Flag Spa Unesco World Heritage Sites Authentic Italian villages Wine cellars Tourist information centres Parks and Protected areas Bike Park Tourist information points Marina Aqua park MARCHE 2019 2021 Events, places and experiences for your holiday 3 Capital of the Italian Renaissance and birthplace of Raffaello Sanzio years 2019 2021 MARCHE AN OPEN-AIR STAGE Come to Marche! Between 2018 and 2021 the region becomes an open-air stage hosting exhibitions, events, and shows which celebrate its most famous sons: Rossini, Leopardi, and Raffaello. But the events and celebrations will be the driving force in promoting the excellence of the region, offering an extraordinary cultural heritage showcased in the names of Lorenzo Lotto, Frederick II Hohenstaufen, Leonardo, and Dante Alighieri. 48 year 2019 THE OPERA TRADITION OF Marche MARCHE 2019 2021 Events, places and experiences for your holiday 5 Theatre “dell'Aquila” Fermo In 2019 will continue the festivities commemorating 150 years since the death of Gioachino Rossini, the famous composer born in Pesaro in 1792, and deceased in Passy, Paris in 1868. For Pesaro, a UNESCO City of Music, 2018 has already marked the beginning of a rich program of celebrations honouring Rossini that complemented the ROF (Rossini Opera Festival), the annual theatre festival dedicated to the works of the artist from Pesaro. -

Mirino Su Monte Urano E Circuito Del Porto

BERGAMO (BG), 3 maggio 2019 COMUNICATO STAMPA 034/03-05-2019 Team Colpack: mirino su Monte Urano e Circuito del Porto BERGAMO (BG) – Un doppio appuntamento attende il Team Colpack nel prossimo fine settimana. Domani la squadra bergamasca parteciperà al 4° Trofeo Comune di Monte Urano – 12° Memorial Ippolito Matricardi, che si corre nelle Marche a Monte Urano, in provincia di Fermo. Domenica 5 maggio appunramento per le ruote veloci con l’internazionale 53° Circuito del Porto a Cremona. Il Team Colpack è reduce da un periodo molto positivo: il 1° maggio era arrivata la settima vittoria stagionale con Davide Baldaccini alla Coppa Penna, prima di lui, in questo inizio di stagione, erano arrivati i colpi di Giulio Masotto al Memorial Polese, la Cronosquadre della Versilia, tre successi individuali di Paolo Baccio, nella cronometro di Montecassiano, a Castiglion Fibocchi e a Vittorio Vento, oltre al prestigioso successo di Andrea Bagioli nell’internazionale di San Vendemiano. La squadra del team manager Antonio Bevilacqua si presenta motivata ai due nuovi appuntamenti in calendario con l’intenzione di regalare una nuova gioia al presidente Beppe Colleoni. -- Giorgio Torre Addetto Stampa Team Colpack Cell. +39 329.4131701 e-mail: [email protected] Sito internet: www.teamcolpack.it English Version PRESS RELEASE Team Colpack: target on Monte Urano and the Circuito del Porto BERGAMO (ITALY) – A double date awaits the Team Colpack next weekend. Tomorrow the team from Bergamo will take part in the 4th Trofeo Comune di Monte Urano - 12th Memorial Ippolito Matricardi, which is held in the Marche region in Monte Urano, in the province of Fermo. -

Andrea Brusaferro Curriculum Vitae

ANDREA BRUSAFERRO CURRICULUM VITAE Data details Education Occupation Scientific research Wildlife management Impact assessments Consultancy and organitations Teaching activities Conferences Languages and software Publications Brusaferro Andrea Curriculum Vitae DATA DETAILS Date of birth : September 12, 1965 Birthplace : MILANO (MI) Tax code : BRS NDR 65P12 F205O Professional activities : Research and Experimental Development in Natural Sciences VAT number : 01549610432 Residence : Fraz MERGNANO S.SAVINO n.8 - 62032 CAMERINO (MC) Marital Status : MARRIED Sons : ONE Phone : +39 0737 644372 / +39 327 2896687 E-mail : [email protected] and [email protected] Military Service : July 1990 - June 1991 (Appointed as a radio operator) Foreign Language : English (written and spoken) EDUCATION 1979 - 1984 High School "Leonardo da Vinci" Civitanova Marche (MC) o Scientific maturity. o Vote 46/60 1985 - 1990 University of Camerino, Camerino (MC) o Degree in Natural Sciences. o 110/110 cum laude . o Thesis: "Morphology of the facial region of the Merops apiaster (Aves, Coraciiformes, Meropidae)" o Teacher Guidae: Prof. Simonetta AM. 1991 - 1994 University of Camerino, Camerino (MC) o PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology "VI cycle”. o PhD thesis: "Comparative Morphology of the skull in Coraciiformes (Aves). o Teacher Guide: Prof. Simonetta AM. 2 Brusaferro Andrea Curriculum Vitae 1997 University of Rome "La Sapienza" Roma o Laboratory of geometric morphometry. o Topic: Analysis of the shape and size of organisms through the geometric morphometry. o Teacher: Prof. F.J. Rohlf 2006 University of Urbino "Carlo Bo" Urbino (PU) o Professional course. o Topic: Introduction to ArcView and ArcInfo for ArcGis rel. 9.x (basic and advanced course). o 32 hours o Teacher: Prof. -

Issue 197.Pmd

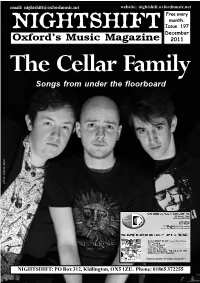

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 197 December Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 The Cellar Family Songs from under the floorboard photo: Johnny Moto NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net taken control of the building three years ago after Solarview, the company that refurbished it after years of neglect, went into liquidation. Trouble at a couple of club nights in the past had earned The Regal a bad reputation in certain sections of the press, but more recently the building looked like it was set to fulfil its potential as the biggest dedicated live music venue in Oxford. SECRET RIVALS release a new single next month. ‘Once More M83 have added a date at the O2 Academy on Tuesday 24th January With Heart’ b/w ‘I Know to their UK tour. The band, centred around French musician and Something’ is released on It’s All producer Anthony Gonzalez, recently followed up their acclaimed JONQUIL return to town for a Happening Records on January 2008 album `Saturdays = Youth’ with new album, `Hurry Up, We’re special Blessing Force-themed 16th. Visit www.secretrivals.com Dreaming. Tickets, priced £12.50, are on sale now from the venue box show at the O2 Academy on for more news on the band. office. Saturday 17th December. They are THE HORRORS, meanwhile, have re-arranged their Academy joined for the night by Pet Moon, THE ORIGINAL RABBIT FOOT show for Thursday 19th January after their original date in October Sisterland and Motherhood as well SPASM BAND play a fundraising was postponed when singer Faris Badwan lost his voice. -

Rete Museale Della Provincia Difermo

RETE MUSEALE DELLA PROVINCIA DI FERMO RETE MUSEALE DELLA PROVINCIA DI FERMO WWW.MUSEICOMUNI.IT Costo da tel. fisso Telecom Italia 10 cent. al min. IVA incl. senza scatti alla risposta tutti i giorni 24/24 h. Altro operatore contattare servizio clienti. attivo dal lunedì al venerdì from monday to friday 09.00 -15.00 (escluso i festivi / week days only) [email protected] Ente promotore in collaborazione con Provincia di Fermo Anita Pagani Assessorato alla Cultura Funzionario del Servizio Cultura e Pubblica Istruzione della Provincia di Fermo Comune capofila Giampiera Mentili Comune di Fermo Funzionario del Servizio Cultura e Pubblica Assessorato alla Cultura Istruzione della Provincia di Fermo Progetto grafico Direzione Monica Simoni Giovanni Della Casa Visual designer socio TPP Dirigente del Servizio Cultura e Pubblica Istruzione Referenze fotografiche della Provincia di Fermo Archivi fotografici degli enti aderenti Manilio Grandoni Giancarlo Postacchini (Palazzo dei Priori) Dirigente Settore Beni Roberto Dell’Orso e Attività Culturali (Pinacoteca Civica di Fermo) Sport e Turismo Daniele Maiani del Comune di Fermo (Sala del Mappamondo e Mostra Archeologica permanente di Fermo) Coordinamento Domenico Oddi e redazione (Museo Diocesano di Fermo) Servizio Musei Mirco Moretti del Comune di Fermo (Museo dei Fossili di Sant’Elpidio a Mare) Alessandro Tossici Società Cooperativa (Musei dei Fossili di Smerillo) Sistema Museo La Provincia e il Comune di Fermo sono Contenuti a disposizione degli aventi diritto per le A cura del gruppo di lavoro fonti iconografiche non identificate. composto da: Giuseppe Buondonno Si ringraziano tutti i proprietari e gestori Assessore alla Cultura dei musei per la gentile collaborazione. Provincia di Fermo I dati pubblicati sono stati forniti dai Francesco Trasatti singoli enti aderenti. -

Between Two Languages: the Linguistic Repertoire of Italian Immigrants in Flanders

Between Two Languages: The Linguistic Repertoire of Italian Immigrants in Flanders Stefania Marzo K.U.Leuven 1 Introduction This paper is part of a larger, ongoing PhD-project carried out at the K.U.Leuven in Belgium. The project investigates the linguistic effect of intensive bilingualism on Italian as a subordinate language for two generations of Italian-Dutch bilinguals who reside in Limburg, the easternmost region of Flanders, Belgium. The study examines language contact phenomena (language variation and language change) and specific speech patterns and the main purpose is to determine whether different types of grammatical phenomena (morphological, syntactic and lexical) in the speech of bilinguals are affected by language contact in the same way. It also seeks to determine whether the identified changes can be explained on the basis of the processes that are recognized in the literature (Muysken 2001; Silva- Corvalán 1994; Van Coetsem 1995) as characteristic of language contact, namely simplification and transfer. Finally, the project verifies in which way these features correlate with social factors. Until now very few studies on ‘migrant Italian’ in Europe have been carried out up, and most of them have focused on language attrition of the first generation. As far as concerns the Italian language in Belgium, most of the studies on second generation Italians in Flanders concern language behaviour, as eg. language shift (Jaspaert & Kroon 1991) or school problems of children of migrant workers (Jacqmain 1978a; 1978b; 1979). For the second1 and third generation Italians, which constitute the group we have opted for, the concept of language loss is composite. -

Colby College Catalogue 1945 - 1946

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Catalogues Colby College Archives 1945 Colby College Catalogue 1945 - 1946 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/catalogs Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby College Catalogue 1945 - 1946" (1945). Colby Catalogues. 38. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/catalogs/38 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. .·-. · :<: �·-�.-���- : ;:jWf5'�1:·;�.. � zz�,�1�¥�i��t�t ... ,. _ . _· { ' I ' ' COLBY COLLEGE LIBRARY WATERVILLE, MAINE / I .----------.. ' • : . .-1 (, c�'.'F :�. College Calendar, 1945-1946 FIRST SEMESTER SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 22-Freshman Week begins. THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 27-Upperclass Registration. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28-Classes begin. \VEDNESDAY Noo'N, NOVEMBER 21, TO 7:50 A.M., FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 23- Thanksgiving Recess. FRIDAY NooN, DECEMBER 14, TO 7:50 A.M., THURSDAY, JANUARY 3- Christmas Recess. SATURDAY, JANUARY 26--Semester Classes end. WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 30, TO FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8-Semester Examinations. SECOND SEMESTER TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 12-Registration. WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 13-Classes begin. THURSDAY NooN, MARCH 21, TO 7:50 A.M., TUESDAY, APRIL 2-Spring Recess. WEDNESDAY, MAY 29-Classes end. MONDAY, JUNE 3 TO THURSDAY, JUNE 13-Final Examinations. SUNDAY, JUNE 16--Commencement. 2 COLBY CGLLf£1: LIERARl Table, of Contents I. DESCRIPTION OF THE COLLEGE Heritage of the Years ..................... ...............· . 7 A Liberal Education . 10 A Living and a Life . 12 Colby in Wartime . 13 Veterans' Education . .. 14 Location and Plant .