ZAPA's Position on Chapter 1 and 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear President, Dear Ursula, We Welcome the Letter of 1 March That

March 8, 2021 Dear President, dear Ursula, We welcome the letter of 1 March that you received from Chancellor Merkel and PM Frederiksen, PM Kallas and PM Marin. We share many of the ideas outlined in the letter. Indeed, there are some points that we find are of particular importance as we work to progress the digital agenda for the EU. We certainly agree that our agenda must be founded on a good mix of self-determination and openness. Our approach to digital sovereignty must be geared towards growing digital leadership by preparing for smart and selective action to ensure capacity where called for, while preserving open markets and strengthening global cooperation and the external trade dimension. Digital innovation benefits from partnerships among sectors, promoting public and private cooperation. Translating excellence in research and innovation into commercial successes is crucial to creating global leadership. The Single Market remains key to our prosperity and to the productivity and competitiveness of European companies, and our regulatory framework needs to be made fit for the digital age. We need a Digital Single Market for innovation, to eliminate barriers to cross-border online services, and to ensure free data flows. Attention must be paid to the external dimension where we should continue to work closely with our allies around the world and where in our interest, develop new partnerships. We need to make sure that the EU can be a leader of a responsible digital transformation. Trust and innovation are two sides of the same coin. Europe’s competitiveness should be built on efficient, trustworthy, transparent, safe and responsible use of data in accordance with our shared values. -

How Poland's EU Membership Helped Transform Its Economy Occasional

How Poland’s EU Membership Helped Transform its Economy Marek Belka Occasional Paper 88 Group of Thirty, Washington, D.C. About the Author Marek Belka is the President of the National Bank of Poland. After completing economic studies at the University of Łódź in 1972, Professor Belka worked in the university’s Institute of Economics. He earned a PhD in 1978 and a postdoctoral degree in economics in 1986. Since 1986, he has been associated with the Polish Academy of Sciences. During 1978–79 and 1985–86, he was a research fellow at Columbia University and the University of Chicago, respectively, and in 1990, at the London School of Economics. He received the title of Professor of Economics in 1994. Since the 1990s, Professor Belka has held important public positions both in Poland and abroad. In 1990, he became consultant and adviser at Poland’s Ministry of Finance, then at the Ministry of Ownership Transformations and the Central Planning Office. In 1996, he became consultant to the World Bank. During 1994–96, he was Vice-Chairman of the Council of Socio-Economic Strategy at Poland’s Council of Ministers, and later economic adviser to the President of the Republic of Poland. Professor Belka served as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance on two occasions—in 1997, in the government of Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, and during 2001–02, in the government of Leszek Miller. During 2004–05, he was Prime Minister of Poland. Since 2006, Professor Belka has been Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, and since January 2009, he has been Director of the European Department at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). -

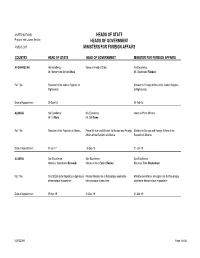

HEADS of STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS of GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS for FOREIGN AFFAIRS

UNITED NATIONS HEADS OF STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS OF GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFGHANISTAN His Excellency Same as Head of State His Excellency Mr. Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Mr. Salahuddin Rabbani Full Title President of the Islamic Republic of Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic Afghanistan of Afghanistan Date of Appointment 29-Sep-14 02-Feb-15 ALBANIA His Excellency His Excellency same as Prime Minister Mr. Ilir Meta Mr. Edi Rama Full Title President of the Republic of Albania Prime Minister and Minister for Europe and Foreign Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the Affairs of the Republic of Albania Republic of Albania Date of Appointment 24-Jul-17 15-Sep-13 21-Jan-19 ALGERIA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monsieur Abdelkader Bensalah Monsieur Nour-Eddine Bedoui Monsieur Sabri Boukadoum Full Title Chef d'État de la République algérienne Premier Ministre de la République algérienne Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République démocratique et populaire démocratique et populaire algérienne démocratique et populaire Date of Appointment 09-Apr-19 31-Mar-19 31-Mar-19 31/05/2019 Page 1 of 66 COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANDORRA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monseigneur Joan Enric Vives Sicília Monsieur Xavier Espot Zamora Madame Maria Ubach Font et Son Excellence Monsieur Emmanuel Macron Full Title Co-Princes de la Principauté d’Andorre Chef du Gouvernement de la Principauté d’Andorre Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Principauté d’Andorre Date of Appointment 16-May-12 21-May-19 17-Jul-17 ANGOLA His Excellency His Excellency Mr. -

Poland by Anna Wójcik Capital: Warsaw Population: 37.95 Million GNI/Capita, PPP: $26,770

Poland by Anna Wójcik Capital: Warsaw Population: 37.95 million GNI/capita, PPP: $26,770 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores NIT Edition 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 National Democratic Governance 3.25 3.25 2.75 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.75 3.25 4.00 Electoral Process 2.00 1.75 1.50 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 Civil Society 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.75 2.00 Independent Media 2.00 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.75 3.00 3.00 Local Democratic Governance 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.75 2.00 Judicial Framework and Independence 2.25 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.75 3.25 4.25 Corruption 2.75 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 Democracy Score 2.25 2.32 2.21 2.14 2.18 2.18 2.21 2.32 2.57 2.89 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. -

La Fondation Robert Schuman

Having problems in reading this e-mail? Click here Tuesday 16th January 2018 issue 787 The Letter in PDF format The Foundation on and The foundation application available on Appstore and Google Play Catalonia: the lie of the land after the battle Author: Angel Sanchez Navarro On 21st December the Catalans voted. Nearly a month later we can put forward the first ideas about the results, their meaning and the impact these might have. Whilst in society and the Spanish Parliament there is a very wide majority in support of the respect of the rules of the game, the ballot boxes have revealed a deeply divided society in two quantitatively similar blocks, although one of them has been in government for nearly forty years. Read more Elections : Czech Republic Commission : Priorities 2018 - Budget - Supercomputers - Digital - Sustainable development Council : Bulgaria - Eurogroup - Korea/Sanctions Diplomacy : Iran/Nuclear - Iraq Court of Justice : Morocco Court of Auditors : Regions Germany : Coalition Austria : France Bulgaria : Anti-corruption France : Italy - China Italy : Summit/Europe-South Poland : Relations/EU - Re-shuffle Romania : Government/Resignation UK : Re-shuffle Slovenia : Croatia Sweden : NATO Eurostat : Unemployment - Trade Studies/Reports : Impact/Brexit Culture : Exhibition/Vienna - Exhibition/Paris - Design/Cologne Agenda | Other issues | Contact Elections : Milo Zeman and Jiri Drahos will face each other in the second round of the Czech Presidential election Outgoing President of the Czech Republic, Milos Zeman (Citizens Rights Party - SPOZ) came out ahead in the first round of the presidential election on 12th and 13th January 38.56% of the vote. In the 2nd round on 26th and 27th January, he will face Jiri Drahos (independent), the former President of the Academy of Science who has the support of the People's Christian-Democratic Union (KDU-CSL), (a centrist party led by Pavel Belobradek), and the movement Mayors and Independents (STAN), (a party led by Petr Gazdik, who won 26.60% of the vote). -

RJEA Vol19 No2 December2019.Cdr

Title: Common Interests and the Most Important Areas of Political Cooperation between Poland and Romania in the Context of the European Union Author: Justyna Łapaj-Kucharska Citation style: Łapaj-Kucharska Justyna. (2019). Common Interests and the Most Important Areas of Political Cooperation between Poland and Romania in the Context of the European Union. "Romanian Journal of European Affairs" (2019, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 63-86). ROMANIAN JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN AFFAIRS Vol. 19, No. 2, December 2019 Common Interests and the Most Important Areas of Political Cooperation between Poland and Romania in the Context of the European Union Justyna Łapaj-Kucharska1 Abstract: The article addresses several issues that constitute the main areas of Polish-Romanian relations in the 21st century in the political dimension and in the broad sense of security. Relations between Poland and Romania have been characterized in the context of the membership of both countries in the European Union. Particular emphasis was placed on the period of the Romanian Presidency of the Council of EU, which lasted from January to the end of June 2019. The article indicates the most important common interests of both countries, the ways for their implementation, as well as potential opportunities for the development of bilateral and multilateral cooperation. The article also takes into account the key challenges that Poland and Romania must face in connection with EU membership. Keywords: Romania, Poland, European Union, Three Seas Initiative, multilateral cooperation. Introduction Polish-Romanian relations were particularly close in 1921-1939, when Romania was the only neighbour, apart from Latvia, who was Poland's ally. -

1 H.E. Mr Andrzej Duda, President of the Republic of Poland H.E. Mr

H.E. Mr Andrzej Duda, President of the Republic of Poland H.E. Mr Tomasz Grodzki, Marshal of the Senate of the Republic of Poland H.E. Ms Elżbieta Witek, Marshal of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland H.E. Mr Mateusz Morawiecki, Prime Minister of the Republic of Poland 8 June 2020 Excellencies, On 19 March 2020 the Bar Council of England and Wales (Bar Council) and the Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales (BHRC) wrote to you to express grave concern as to the motion filed by the National Prosecution Office to the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court (Disciplinary Chamber) to waive the immunity of Judge Igor Tuleya. We called upon the relevant Polish authorities to respect their obligations under the Polish Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights, and European Union law; to comply with the judgment of the Supreme Court of 5 December 2019; to respect the resolution of the Polish Supreme Court of 23 January 2020; to refrain from actions and statements attacking and vilifying judges and prosecutors; and to take all necessary measures to suspend the operation of the Disciplinary Chamber and end the politicisation of the new National Council of the Judiciary. We called for the arbitrary motion against Judge Igor Tuleya to be withdrawn without delay. We understand that there is to be a hearing of the motion on 9 June 2020. Since 19 March there have been important developments. On 8 April 2020 the Court of Justice of European Union specified in Case C-791/19 R (Commission v Poland) that Poland must immediately suspend the application of the national provisions on the powers of the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court with regard to disciplinary cases concerning judges. -

Poland Political Briefing: Political Crisis and Changes in the Composition of the Government Joanna Ciesielska-Klikowska

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 33, No. 1 (PL) October 2020 Poland political briefing: Political crisis and changes in the composition of the government Joanna Ciesielska-Klikowska 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: CHen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 Political crisis and changes in the composition of the government Last weeks have brought an almost never-ending discussion about changes in the government and its planned reconstruction. It is a rare procedure in the Polish political system under which some ministers lose their powers and new ones appear on the stage. Unexpectedly, however, the Animal Protection Act shook the talks and caused a serious political crisis. The reconstruction that followed the crisis is very far-reaching and shows who is genuinely ruling the country. Political crisis related to the Animal Protection Act The debate about reducing the number of ministries, changing their competences or powers of individual ministers had already been going on throughout the summer period (see Poland 2020 September Domestic Policy Briefing). When it seemed that the three parties which create the ruling coalition of the United Right (Law and Justice Party, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS; United Poland; Solidarna Polska; Agreement, Porozumienie Jarosława Gowina) were already agreeing on the appearance of the new government, one vote shocked the political scene and public opinion. A real game changer was the voting on the Animal Protection Act (so-called "five for animals" act), which entered the deliberations of the parliament on September 18, and was voted shortly after by a large part of the political circles represented in the SeJm. -

Druk Nr 3069 Warszawa, 23 Listopada 2018 R

Druk nr 3069 Warszawa, 23 listopada 2018 r. SEJM RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ VIII kadencja Pan Marek Kuchciński Marszałek Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Na podstawie art. 158 ust. 1 Konstytucji Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej oraz art. 115 ust. 1 regulaminu Sejmu niżej podpisani posłowie składają wniosek: - o wyrażenie wotum nieufności Radzie Ministrów kierowanej przez Prezesa Rady Ministrów Pana Mateusza Morawieckiego i wybranie Pana Grzegorza Schetyny na Prezesa Rady Ministrów. Do reprezentowania wnioskodawców upoważniamy pana posła Grzegorza Schetynę. (-) Zbigniew Ajchler; (-) Bartosz Arłukowicz; (-) Paweł Arndt; (-) Urszula Augustyn; (-) Joanna Augustynowska; (-) Tadeusz Aziewicz; (-) Paweł Bańkowski; (-) Anna Białkowska; (-) Jerzy Borowczak; (-) Krzysztof Brejza; (-) Bożenna Bukiewicz; (-) Małgorzata Chmiel; (-) Alicja Chybicka; (-) Janusz Cichoń; (-) Piotr Cieśliński; (-) Tomasz Cimoszewicz; (-) Zofia Czernow; (-) Andrzej Czerwiński; (-) Ewa Drozd; (-) Artur Dunin; (-) Waldy Dzikowski; (-) Joanna Fabisiak; (-) Joanna Frydrych; (-) Grzegorz Furgo; (-) Krzysztof Gadowski; (-) Zdzisław Gawlik; (-) Stanisław Gawłowski; (-) Lidia Gądek; (-) Elżbieta Gelert; (-) Artur Gierada; (-) Marta Golbik; (-) Cezary Grabarczyk; (-) Jan Grabiec; (-) Rafał Grupiński; (-) Andrzej Halicki; (-) Agnieszka Hanajczyk; (-) Bożena Henczyca; (-) Jolanta Hibner; (-) Marek Hok; (-) Maria Małgorzata Janyska; (-) Bożena Kamińska; (-) Włodzimierz Karpiński; (-) Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska; (-) Joanna Kluzik-Rostkowska; (-) Magdalena Kochan; (-) Agnieszka Kołacz-Leszczyńska; -

Human Rights Reports in Europe

HUMAN RIGHTS IN EUROPE REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Cover photo: Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed A protester speaks through a megaphone as under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, smoke from coloured smoke bombs billows near international 4.0) licence. people taking part in the annual May Day rally in https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Strasbourg, eastern France, on May 1, 2019. For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: © PATRICK HERTZOG/AFP via Getty Images www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: EUR 01/2098/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS REGIONAL OVERVIEW 4 ALBANIA 8 AUSTRIA 10 BELGIUM 12 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 14 BULGARIA 16 CROATIA 18 CYPRUS 20 CZECH REPUBLIC 22 DENMARK 24 ESTONIA 26 FINLAND 27 FRANCE 29 GERMANY 32 GREECE 35 HUNGARY 38 IRELAND 41 ITALY 43 LATVIA 46 LITHUANIA 48 MALTA 49 MONTENEGRO 51 THE NETHERLANDS 53 NORTH MACEDONIA 55 NORWAY 57 POLAND 59 PORTUGAL 62 ROMANIA 64 SERBIA 66 SLOVAKIA 69 SLOVENIA 71 SPAIN 73 SWEDEN 76 SWITZERLAND 78 TURKEY 80 UK 84 HUMAN RIGHTS IN EUROPE 3 REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International campaigns, harassment, and even In 2019, founding values of the European administrative and criminal penalties. -

Letter from 55 Civil Society Organisations to EU Heads Of

To: Federal Chancellor of Austria, Sebastian Kurz; Prime Minister of Belgium, Charles Michel; Prime Minister of Bulgaria, Boyko Borissov; Prime Minister of Croatia, Andrej Plenkovic; President of the Republic of Cyprus, Nicos Anastasiades; Prime Minister of Czech Republic, Andrej Babis; Prime Minister of Denmark, Lars Lokke Rasmussen; Prime Minister of Estonia, Juri Ratas; Prime Minister of Finland, Juha Sipila; President of the Republic of France, Emmanuel Macron; Federal Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel; Prime Minister of Greece, Alexis Tsipras; Prime Minister of Hungary, Viktor Orban; Taoiseach of Ireland, Leo Varadkar; Prime Minister of Italy, Giuseppe Conte; Prime Minister of Latvia, Krisjanis Karins; President of Lithuania, Dalia Grybauskaite; Prime Minister of Luxembourg, Xavier Bettel; Prime Minister of Malta, Joseph Muscat; Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Mark Rutte; Prime Minister of Poland, Mateusz Morawiecki; Prime Minister of Portugal, Antonio Costa; President of Romania, Klaus Werner Iohannis; Prime Minister of Slovakia, Peter Pellegrini; Prime Minister of Slovenia, Marjan Sarec; President of the Government of Spain, Pedro Sanchez; Prime Minister of Sweden, Stefan Lofven. 7th May 2019 Dear Federal Chancellor/President/Prime Minister/Taoiseach, On behalf of 55 civil society organisations from across Europe, we are writing to you to urge you to nominate European commissioners who will support and serve present and future generations, and prioritise environment, quality of life and decent work. Every day, people across Europe struggle with growing poverty and inequality, deteriorating access to healthcare and worrying levels of youth unemployment. Meanwhile, many large companies pollute the environment, refuse to pay their fair share of taxes and wield disproportionate political influence. -

Focus on Poland

Focus on Poland Monthly Newsletter – January Topic of the month Murder of Paweł Adamowicz Mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz was murdered during the charity event in his home town. Paweł Adamowicz was 53 years old, and had been mayor for more than 20 years. He was recently re- elected in November 2018 municipal elections. He was seen as an anchor of the rapid transformation of Gdańsk into a modern and open city. He was himself a moderate conservative or centrist politician who was leading one of the most liberal metropolises in Poland. Pawel Adamowicz was often a progressive voice in Polish politics, supporting LGBT+ rights and tolerance for minorities. He marched in last year's gay pride parade, a rare action for a mayor in Poland. He also supported the Jewish community when the city's synagogue had its windows broken last year. He was one of the initiators of creating European Solidarity Center in Gdańsk, interactive museum of the “Solidarność” movement and living monument of Poland’s modern history. Paweł Adamowicz grabbed his stomach and collapsed in front of the audience at the 27th annual fundraiser organised by the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity, Poland’s biggest charity event (organized every January when around 200.000 volunteers collects money to buy hospital equipment). Television footage of the incident showed the mayor speaking to the crowd while holding a sparkler, before his attacker moved towards him. He was resuscitated at the scene and then transported to the Medical University. After carrying out the attack, the man shouted from the stage “I was jailed but innocent.