Talk Emigholz Wyborny (English Version).Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science And

ARCHITECTURE The Irwin S. Chanin AT COOPER School of Architecture The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art 4:09 -10 The academic year 2009 –20010 was a particularly significant The three exhibitions collectively served as an opportunity We were brought more forcefully to reflect on this tradition, year for The Cooper Union, and equally so for the School for the School of Architecture to reflect on its history and to by the passing this year of two of its major inventors, of Architecture. As the 150th year since the founding of the clarify and articulate a curriculum for the education of Professors Richard Henderson and Raimund Abraham. institution, it was also the 149th year of teaching architecture architects into the twenty first century. In their preparation Richard, who taught at the school for over thirty years, was at Cooper. A timeline included in last year’s edition of we were able to reflect on the extraordinary intersection not only a wise and strong administrator but, more importantly , was further developed and illustrated of tradition, renewal, and innovation represented in the work Architecture At Cooper an innovator in the realm of architectural analysis and one as the prologue for the first of three major exhibitions of the school since its foundation. who placed the analytical process at the center of Cooper’s mounted by the school in the Houghton Gallery, “Architecture From the Nine Square Problem, through Cubes, Topos, approach to design. At a time when the “postmodernists” at Cooper 1859 –2009.” The exhibition chronicled the history Blocks, Bridges, Connections, Communities, Balances, were calling for a return to history in the iconographic and of architecture—and specifically of the architecture of its Walls, Houses, Joints, Skins, to Spheres, Cylinders, Pyramids imitative sense, Richard insisted that analysis was a didactic, buildings—at Cooper from 1859 to the present. -

LE CORBUSIER Heinz IIIII ASGER JORN RELIEF 03126 Pos: 83

Emigholz,LE CORBUSIER Heinz IIIII ASGER JORN RELIEF 03126 pos: 83 © Heinz Emigholz Filmproduktion Le Corbusier [IIIII] Asger Jorn [Relief] Heinz Emigholz 2015, DCP, color, 29 min., without dialogue. Producer Heinz Emig- Le Corbusier [IIIII] Asger Jorn [Relief] contrasts the Villa Savoye, holz, Ruth Baumeister. Production companies Heinz Emigholz built by Le Corbusier in 1931, and Asger Jorn’s Grand Relief, which Filmproduktion (Berlin, Germany), Museum Jorn Silkeborg (Silke- the Danish painter and sculptor produced in 1959 for the Århus borg, Denmark). Written and directed by Heinz Emigholz. Direc- Statsgymnasium. The film makes connections between what, tor of photography Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann. Sound Till according to the ideological stipulations of their creators, does Beckmann. Sound design Jochen Jezussek, Christian Obermaier. not belong together. Editor Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann. World sales Filmgalerie 451. “The film came about because I was intrigued by the premise of Contact: [email protected] comparing two buildings that at first seem to have nothing to do http://www.pym.de with one another. A dialogue between thoroughly stylized clarity and declared wildness, both with ideologically trimmings. It was only by working on the film that I learned to appreciate the two works that had once left me indifferent: the delight of their crea- tors in the productively implemented statement.” Heinz Emigholz berlinale forum expanded 2016 208 In conversation, Heinz Emigholz and Zohar Rubinstein Heinz Emigholz was born in 1948 in Achim, near Bremen. Since 1973, he has worked as a freelance filmmaker, artist, writer, cine- Zohar Rubinstein: How was working at the Le Corbusier villa? matographer, producer, and journalist. -

![Le Corbusier [Iiiii] Asger Jorn [Relief]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2009/le-corbusier-iiiii-asger-jorn-relief-3172009.webp)

Le Corbusier [Iiiii] Asger Jorn [Relief]

FORUM EXPANDED LE CORBUSIER [IIIII] ASGER JORN [RELIEF] Heinz Emigholz LE CORBUSIER [IIIII] ASGER JORN [RELIEF] stellt die 1931 erbaute Deutschland/Dänemark 2015 Villa Savoye von Le Corbusier dem Grand Relief von Asger Jorn 29 Min. · DCP · Farbe gegenüber, das der dänische Maler und Bildhauer 1959 für das Århus Statsgymnasium produzierte. Der Film verbindet damit, was nach Regie, Buch Heinz Emigholz Kamera Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann ideologischer Maßgabe ihrer Macher nicht zusammengehört. k c Ton Till Beckmann e b l e t t e Sound Design Jochen Jezussek, N a r t „Der Film kam deshalb zustande, weil mich die Vorgabe gereizt e Christian Obermaier P : o t o hat, zwei Bauwerke miteinander zu konfrontieren, die erst einmal F Schnitt Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann nichts miteinander zu tun haben. Ein Dialog zwischen durchgestylter Produzent Heinz Emigholz, Heinz Emigholz Heinz Emigholz wurde 1948 in Achim Klarheit und erklärter Wildheit, beide ideologisch verbrämt. Durch die bei Bremen geboren. Seit 1973 ist er als Filmproduktion freischaffender Filmemacher, bildender Arbeit am Film habe ich an beiden Arbeiten überhaupt erst schätzen Produzentin Ruth Baumeister, Museum Jorn Künstler, Kameramann, Autor, Publizist und gelernt, was mir vorher relativ egal war: die Lust ihrer Macher am Silkeborg Produzent tätig. 1974 begann er mit der produktiv umgesetzten Statement.“ Produktion enzyklopädischen Zeichenserie „Die Basis Heinz Emigholz Heinz Emigholz Filmproduktion des Make-Up", der 2007/08 im Berliner Berlin, Deutschland Museum Hamburger Bahnhof eine große [email protected] Einzelausstellung gewidmet war. 1978 gründete er die Produktionsfirma Pym Museum Jorn Silkeborg Films. 1984 war der Auftakt der Filmserie Silkeborg, Dänemark „Photographie und jenseits". -

Innovative Film Austria 07/08

Published by Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture 2007 Vienna — Austria Imprint Contents Federal Ministry for Education, INTRODUCTION 7 Foreword by Federal Minister Claudia Schmied the Arts and Culture — Film Division 9 Foreword by Ed Halter Johannes Hörhan — Director Minoritenplatz 5 1014 Vienna Austria FACTS + FIGURES 12 Budget +43 1 531 15 7530 13 Most Frequent Festival Screenings 1995—2007 [email protected] 13 Most Frequent Festival Screenings 2004—2007 www.bmukk.gv.at 14 Most Frequently Rented 1995—2007 15 Most International Awards Received 1995—2007 Publisher and Concept 16 Promotional Awards Carlo Hufnagl — Film Division 16 Recognition Awards 17 Thomas Pluch Screenplay Award Editors Carlo Hufnagl Irmgard Hannemann-Klinger FILMS 19 Fiction 23 Documentary Translation 33 Avant-garde Eve Heller 37 Fiction Short Graphic Design 43 Documentary Short up designers berlin-wien 49 Avant-garde Short Walter Lendl Print FILMS COMING SOON 63 Fiction Coming Soon REMAprint 71 Documentary Coming Soon 91 Avant-garde Coming Soon 97 Fiction Short Coming Soon 103 Documentary Short Coming Soon 109 Avant-garde Short Coming Soon CONTACT ADDRESSES 123 Production Companies & Sales 124 Directors INDEX 126 Directors 127 Films 4>5 Black Box Austrian avant-garde film continually receives top rankings in the charts of opinion building media such as Les cahiers du cinéma and senses of cinema. Critics from Asia, Australia, Europe and the USA describe Austria as the country of origin for the best films produced by the avant-garde worldwide for over half a century. Mean while, our documentary film production also receives growing international attention and critical acclaim. -

Download Detailseite

Forum/IFB 2005 D’ANNUNZIOS HÖHLE THE BASIS OF MAKE-UP III / MISCELLANEA III D’ANNUNZIO’S CAVE LA CAVERNE DE D’ANNUNZIO Regie: Heinz Emigholz Deutschland MISCELLANEA (III): Photographie und jenseits/ Dokumentarfilme Photography and beyond (Part 10) Jahr 1997-2004 D’ANNUNZIOS HÖHLE: Länge 22 Minuten Photographie und jenseits/ Format 35 mm, 1:1.37 Photography and beyond (Part 8) Farbe Jahr 2002-05 Regie, Kamera, Länge 52 Minuten Schnitt Heinz Emigholz Format DigiBeta, Farbe Mitarbeit Irene von Alberti Regie, Buch Heinz Emigholz Heiner Büld Kamera Irene von Alberti Ueli Etter Heinz Emigholz May Rigler Elfi Mikesch Frieder Schlaich Klaus Wyborny Thomas Wilk Schnitt Jörg Langkau Tonbearbeitung Christian Obermaier Sounddesign Frank Kruse Matthias Schwab Mischung Matthias Schwab Mitarbeit Christoph Amshoff Produktion/Weltvertrieb Angela Christlieb Pym Films Dieter Brehde Postfach 630111 THE BASIS OF MAKE-UP III Jan Witzel D-10266 Berlin Musik Claude Debussy [email protected] Brian Eno D’ANNUNZIOS HÖHLE www.pym.de David Byrne „Filme – und das ist jetzt schon fast das Mission Statement der ‚Photographie Produzenten Frieder Schlaich und jenseits‘-Serie – könnten … Teile eines neuartigen Denkgebäudes bil- Irene von Alberti den. Verbal schweigen diese Filme, aber sie ermöglichen es, in dem vorge- Redaktion Wilfried Reichart Co-Produktion WDR, Köln führten Raum zu denken. Der Grat zwischen einer banalen Verdopplung und einer in die Zeit der Betrachtung gehobenen Gleichzeitigkeit ist dabei Produktion/Weltvertrieb sehr schmal und wird sicher nur durch die Qualität der Kinematographie Filmgalerie 451 entschieden“, so Heinz Emigholz. Torstr. 231 D‘ANNUNZIOS HÖHLE zeigt 15 Räume der 1921 von Gabriele d‘Annunzio D-10115 Berlin [email protected] bezogenen und bis zu seinem Tod 1938 bewohnten Villa Cargnacco in Gar- www.filmgalerie451.de done am Gardasee. -

Heinz Emigholz: the Airstrip

october 29 fall 2015 6 p.m. heinz emigholz: the airstrip Presented in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut Chicago as part of the Buildings and sculptures Chicago Architecture Biennial. The film The Airstrip was shot from March 2011 to June 2012 in Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico, Brazil, the United States, Heinz Emigholz (1948, Achim, Germany) is an artist, director, writer, the Northern Mariana Islands and Japan. It shows the following buildings and producer. He trained as a draughtsman before studying philosophy and sculptures: and literature at the University of Hamburg. A major figure in German independent and experimental cinema, Emigholz has produced more than Prometheus Bound (1899) by Reinhold Begas in Berlin, Germany, Mul- 90 long and short films, ranging from theatrical features to experimental berry Harbour (1944) by Winston S. Churchill in Arromanches, France, documentary. Described by Variety as the “most accurate observer of Pantheon (2nd century AD) in Rome, Italy, Hala Ludowa (1913) by Max architecture,” Emigholz is dedicated to origins, the fate, the triumph, Berg in Wrocław, Poland, Department Store (1913) by Carl Schmanns and end of architectural Modernism. From 1993–2013 he served on the in Görlitz, Germany, La Vache Noir Shopping Centre (2000s) in Arceuil, faculty of the Berlin University of the Arts. He has been the subject of France, Gustave Eiffel Monument (1928) by Auguste Perret in Paris, numerous surveys and retrospectives internationally, most recently at France, Market Hall (1953) by Renato Bernadi in Bologna, Italy, Madrid the National Gallery in Washington DC, Centro Cultural in São Paulo, Airport, Mercado de Abasto Shopping Centre (1934) by Viktor Suli in Bue- Instituto Moreira Salle in Rio de Janeiro, and XV International Biennial of nos Aires, Argentina, La Bombonera Stadium (1940) by Viktor Suli and Architecture of Buenos Aires.His work is distributed by Pym Films and José Luis Delpini in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Three Mausoleums (1930s Filmgalerie 451. -

SCHINDLERS HÄUSER Forum SCHINDLER’S HOUSES LES MAISONS DE SCHINDLER Regie: Heinz Emigholz

Berlinale 2007 SCHINDLERS HÄUSER Forum SCHINDLER’S HOUSES LES MAISONS DE SCHINDLER Regie: Heinz Emigholz Österreich/Deutschland 2007 Dokumentarfilm Sprecher Christian Reiner Länge 99 Min. Format 35 mm, 1:1.37 Farbe Stabliste Konzept, Regie, Kamera, Schnitt Heinz Emigholz Kameraassistenz Volkmar Geiblinger Schnittassistenz Markus Ruff Sounddesign Jochen Jezussek Christian Obermaier Originalton May Rigler Mischung Eckart Goebel Produktionsltg. Alexander Glehr Prod.koordination USA May Rigler Produzenten Gabriele Kranzelbinder Alexander Dumreicher- Skolnik House (1950 –52) in Los Feliz Ivanceanu Co-Produzent Heinz Emigholz Redaktion Johanna Hanslmayr, SCHINDLERS HÄUSER – PHOTOGRAPHIE UND JENSEITS, TEIL 12 ORF Der Film zeigt in chronologischer Reihenfolge vierzig Bauwerke des öster- Jutta Krug, WDR III reichisch-amerikanischen Architekten Rudolph Schindler (1887–1953) aus Reinhard Wulf, den Jahren 1921 bis 1952. Schindlers pionierhafte Arbeit in Südkalifornien WDR/3sat Co-Produktion Heinz Emigholz begründete einen eigenen Zweig der architektonischen Moderne. Alle Auf - Filmproduktion, nahmen zum Film fanden im Mai 2006 statt. Der Film bildet damit auch ein Berlin aktuelles Porträt städtischen Wohnens in Los Angeles, das in dieser Aus - ORF, Wien formung noch nie dokumentiert worden ist. WDR III, Köln „1975 bin ich durch Zufall am Lovell House in Newport Beach vorbeige- WDR/3sat, Köln kommen. Der Bau kam mir auf den ersten Blick zugleich eigenartig und Produktion sinnvoll vor. Aber zu der Zeit war ich als Filmemacher mit extrem zeitanaly- Amour Fou Filmproduktion tischen Kompositionen beschäftigt, kein Gedanke an Architekturen außer- Lindengasse 32 halb des Mediums Zeit. Die Ausdehnung meiner filmischen Arbeit auf A-1070 Wien Raumfragen und Raumdarstellungen kam erst später. Ich hatte die Tel.: 1-99 49 91 10 Fax: 1-99 49 91 120 Begegnung mit dem Haus auch vergessen, bis ich es auf der Drehreise im www.amourfou.at Mai 2006 wiedererkannte. -

Rencontres Internationales Paris/Berlin New Cinema and Contempory Art

RENCONTRES INTERNATIONALES PARIS/BERLIN new cinema and contempory art PRESS RELEASE PRÉFET DE LA RÉGION PRESS KIT | RENCONTRES INTERNATIONALES PARIS/BERLIN | APRIL 10-15, 2018 | PARIS 1 SOMMAIRE LES RENCONTRES INTERNATIONALES 3 PARIS/BERLIN 3 VALIE EXPORT 4 HEINZ EMIGHOLZ 6 EIJA-LIISA AHTILA 8 ROSA BARBA 9 LOUIDGI Beltrame 10 SEBASTIAN DIAZ MORALES 11 JON RAFMAN 12 HANS OP DE BEECK 13 JOHAN GRIMONPREZ 14 SALOMÉ LAMAS 16 LASSE LAU 17 VÉRÉNA paravel 18 AND LUCIEN castainG-taYLOR 18 LAURE PROUVOST 19 MAYA SCHWEIZER 21 GEORGE Drivas 22 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 24 VISIT US IN paris 26 PARTNERS 27 LES RENCONTRES INTERNATIONALES PARIS/BERLIN NEW CINEMA AND CONTEMPORY ART Our contemporary visual culture is located at the interjection of esthetic, social and political questionnings of our times, and issues linked to the evolution of production and diffusion modes. Rencontres Internationales Paris/Berlin proposes to explore these practices and their evolutions. From 10 to 15 April in Paris, the Rencontres Internationales creates a space for discovery and reflection dedicated to moving image contemporary practices. Between new cinema and contemporary art, this unique platform in Europe offers a rare opening for contemporary audiovisual creation. Documentary approaches, experimental fictions, videos, hybrid forms: the programme is the result of extensive research and invitations to signficant artists from cinema and contemporary art. The event offers an international programme gathering 120 works of 40 countries. By bringing together internationally renowned artists and filmmakers with young and emerging ones, the audience will attend indoor screenings, special events, video programmes, performances and discussions, in the presence of art centres and museums, curators, artists and distributors who will share with the audience their experience and views on new audiovisual practices and issues. -

Rude & Playful Shadows: Collective Performances of Cinema in Cold

Rude & Playful Shadows: Collective Performances of Cinema in Cold War Europe by Megan E Hoetger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphases in Critical Theory and Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Shannon Jackson, Chair Julia Bryan-Wilson Abigail De Kosnik Anton Kaes Spring 2019 Abstract Rude & Playful Shadows: Collective Performances of Cinema in Cold War Europe by Megan E Hoetger Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair “Rude & Playful Shadows: Collective Performances of Cinema in Cold War Europe” is a historical examination, which engages rigorous discursive and performance-based analysis of underground film screening events that crossed the West/East divide and brought together an international group of artists and filmmakers during some of the “hottest” years of the Cold War period. At its center, the study investigates the practices of two pioneering filmmakers, Austrian Kurt Kren (b. Vienna, 1929; d. Vienna, 1998) and German Birgit Hein (b. Berlin, 1942). Tracking their aesthetic, ideological, and spatial reconfigurations of the cinematic apparatus—their “performances of cinema”—in Austria and former West Germany, the dissertation demonstrates how Kren and Hein were progenitors of influential new viewing practices that operated in the tacit geopolitical interstices between nation- states and underground cultures. Contemporary art, film, and media scholarship tends to move in one of two directions: either toward aesthetic inquiries into the appearance of moving images and other time-based arts in the visual art museum since the 1990s, or toward the politics of global media distribution in the digital age. -

![24 Bickels [Socialism]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2394/24-bickels-socialism-5312394.webp)

24 Bickels [Socialism]

Emigholz,BICKELS SOCIALISM Heinz 24 19630 pos: 11 _ © Heinz Emigholz Filmproduktion Bickels [Socialism] Heinz Emigholz Producer Heinz Emigholz, Galia Bar Or. Production companies The ‚Casa do Povo‘ cultural centre in São Paulo, an icon of the secular Jewish Heinz Emigholz Filmproduktion (Berlin, Germany), Mishkan workers‘ movement: a crumbling theatre flanked by staircases, entryways Museum of Art (Ein Harod, Israel). Written and directed by and corridors. Construction noise drones away in the background, clinking Heinz Emigholz. Director of photography Heinz Emigholz, crockery, a broom sweeping over tiled floors, an expressive façade of Till Beckmann. Editor Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann. Sound countless adjustable panes of glass covered by a patina. It’s October design Christian Obermaier. Sound Till Beckmann. 2016 and a group of young people are preparing a preview of Bickels [Socialism]. The venue is to form a prologue to the completed film, which Colour. 92 min. English. tours 22 buildings in Israel designed by Samuel Bickels, most of which Premiere February 12, 2017, Berlinale Forum for kibbutzim. Dining halls, children’s houses, agricultural buildings, bright structures inserted into the Mediterranean landscape with great ingenuity. An architecture with a sell-by date: That many are now empty or have been repurposed at best is linked to the decline of the socialist ideals they embody. Paintings by Jewish artist Meir Axelrod from the Crimea in the 1930s form the epilogue. It tells the tragic story of the Vio Nova kibbutz, which first foundered under the British Mandate in Palestine and later fell victim to Stalinism, before being liquidated entirely under the German occupation. -

Schindlers Häuser Schindler‘S Houses

Schindlers Häuser Schindler‘s Houses Regie: Heinz Emigholz Photographie und jenseits – Teil 12 / Photography and beyond – Part 12 Land: Österreich 2007. Produktion: Amour Fou Filmproduktion, Wien, in Zusammenarbeit mit der Heinz Emigholz Filmproduktion Berlin. Konzept, Regie, Kamera, Schnitt: Heinz Emigholz. Originalton: May Rigler. Kameraassistenz: Volkmar Geiblinger. Schnittassistenz: Markus Ruff. Tongestaltung: Jochen Jezussek, Christian Obermaier. Sprecher: Christian Reiner. Tonmischung: Eckart Goebel. Titel: Martin Putz. Filmgeschäftsführung: Heide Semmelrock. Produktionskoordination USA: May Rigler. Produktionsleitung: Alexander Glehr. Redaktion: Johanna Hanslmayr (ORF), Jutta Krug (WDR), Reinhard Wulf (WDR/3sat). Produzenten: Gabriele Kranzelbinder, Alexander Dumreicher-Ivanceanu. Format: 35mm, 1:1.37, Farbe. Länge: 99 Minuten, 25 Bilder/Sekunde. Originalsprache: Deutsch. Uraufführung: 13. Februar 2007, Internationales Forum, Berlin. Weltvertrieb: Autlook Filmsales, Zieglergasse 75/1, 1070 Wien, Österreich. Tel.: (43) 720 553570, Fax: (43) 720 553572, email: [email protected]; www.autlookfilms.com; Festivals: Austrian Film Commission, Stiftgasse 6, 1070 Wien, Österreich. Tel.: (43-1) 526 33230, Fax: (43-1) 526 6801, email: [email protected]; www.afc.at. Deutscher Verleih: Filmgalerie 451, Saarbrücker Str. 24, 10405 Berlin, Deutschland. Tel.: (49-30) 33982800, Fax: (49-30) 33982810, email: [email protected] Hergestellt mit Unterstützung von Filmfonds Wien und Innovative Film Austria in Zusammenarbeit mit ORF Film-/Fernsehabkommen -

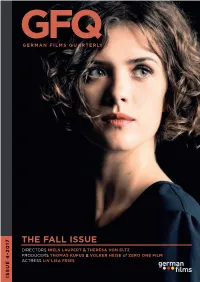

The Fall Issue 1

GFQ4_Druckvorlage_Final.qxp_Layout 1 13.10.17 09:26 Seite 1 GFQ GER MA N F I L M S Q UA R T E RLY 7 THE FALL ISSUE 1 0 DIRECTORS NIELS LAUPERT & THERESA VON ELTZ 2 - PRODUCERS THOMAS KUFUS & VOLKER HEISE of ZERO ONE FILM 4 ACTRESS LIV LISA FRIES E U S S I GFQ4_Druckvorlage_Final.qxp_Layout 1 13.10.17 09:27 Seite 2 CONTENTS GFQ 4-2017 19 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 28 29 30 32 2 GFQ4_Druckvorlage_Final.qxp_Layout 1 13.10.17 09:27 Seite 3 GFQ 4-2017 CONTENTS IN T H I S ISSUE PORTRAITS NEW SHORTS A FRESH PERSPECTIVE FIND FIX FINISH A portrait of director Niels Laupert ................................................. 4 Mila Zhluktenko, Sylvain Cruiziat ................................................... 30 AN EMPATHETIC STORYTELLER GALAMSEY – FÜR EINE HANDVOLL GOLD A portrait of director Theresa von Eltz ............................................. 6 GALAMSEY Johannes Preuss .......................................................... 30 MAKING A MARK LAB/P – POETRY IN MOTION 2 A portrait of the production company zero one film ....................... 8 various directors ............................................................................. 31 BRAINS, BEAUTY & BABYLON BERLIN DAS SATANISCHE DICKICHT – DREI A portrait of actress Liv Lisa Fries ................................................. 10 THE SATANIC THICKET – THREE Willy Hans ............................... 31 WATU WOTE – ALL OF US Katja Benrath .................................................................................. 32 NEWS & NOTES ...............................................................................