David Elsteinv.Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 Elstein, David

www.ssoar.info The political structure of UK broadcasting 1949-1999 Elstein, David Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elstein, D. (2015). The political structure of UK broadcasting 1949-1999. (Media, Democracy & Political Process Series). Lüneburg: meson press. https://doi.org/10.14619/011 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-SA Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-SA Licence Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. (Attribution-ShareAlike). For more Information see: Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de David Elstein POLITICAL The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 STRUCTURE BROADCASTING UK ELSTEIN The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 Media, Democracy & Political Process Series Edited by Christian Herzog, Volker Grassmuck, Christian Heise and Orkan Torun The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 David Elstein Bibliographical Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche National bibliografie (German National Biblio graphy); detailed bibliographic information is available online at http://dnb.dnb.de Published in 2015 by meson press, Hybrid Publishing Lab, Centre for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University of Lüneburg www.mesonpress.com Design concept: Torsten Köchlin, Silke Krieg Cover Image: Sebastian Mühleis and Christian Herzog The print edition of this book is printed by Lightning Source, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom ISBN (Print): 9783957960603 ISBN (PDF): 9783957960610 ISBN (EPUB): 9783957960627 DOI: 10.14619/011 The digital editions of this publication can be downloaded freely at: www.mesonpress.com Funded by the EU major project Innovation Incubator Lüneburg This Publication is licensed under the CCBYSA 4.0 Inter national. -

Culture, Media and Sport Committee

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future of the BBC Fourth Report of Session 2014–15 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 10 February 2015 HC 315 INCORPORATING HC 949, SESSION 2013-14 Published on 26 February 2015 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following Members were also a member of the Committee during the Parliament: David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The Committee is one of the Departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

The Development of the UK Television News Industry 1982 - 1998

-iì~ '1,,J C.12 The Development of the UK Television News Industry 1982 - 1998 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alison Preston Deparent of Film and Media Studies University of Stirling July 1999 Abstract This thesis examines and assesses the development of the UK television news industry during the period 1982-1998. Its aim is to ascertain the degree to which a market for television news has developed, how such a market operates, and how it coexists with the 'public service' goals of news provision. A major purpose of the research is to investigate whether 'the market' and 'public service' requirements have to be the conceptual polarities they are commonly supposed to be in much media academic analysis of the television news genre. It has conducted such an analysis through an examination of the development strategies ofthe major news organisations of the BBC, ITN and Sky News, and an assessment of the changes that have taken place to the structure of the news industry as a whole. It places these developments within the determining contexts of Government economic policy and broadcasting regulation. The research method employed was primarily that of the in-depth interview with television news management, politicians and regulators: in other words, those instrumental in directing the strategic development within the television news industry. Its main findings are that there has indeed been a development of market activity within the television news industry, but that the amount of this activity has been limited by the particular economic attributes of the television news product. -

Culture, Media and Sport Committee

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future of the BBC Fourth Report of Session 2014–15 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 10 February 2015 HC 315 INCORPORATING HC 949, SESSION 2013-14 Published on 26 February 2015 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following Members were also a member of the Committee during the Parliament: David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The Committee is one of the Departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Michael MILNE 2014.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Moving the goalposts: the transformation of television sport in the UK (1992-2014) Michael Milne Faculty of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2014. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e- mail [email protected] MOVING THE GOALPOSTS: THE TRANSFORMATION OF TELEVISION SPORT IN THE UK (1992-2014) MICHAEL MILNE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 Milne | June 2014 2 Abstract Despite its prominence and popularity, television sport remains an under- researched area in media studies and -

A Privatised Future for Channel 4?

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Communications 1st Report of Session 2016–17 A privatised future for Channel 4? Ordered to be printed 4 July 2016 and published 11 July 2016 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 17 Select Committee on Communications The Select Committee on Communications is appointed by the House of Lords in each session “to investigate public policy areas related to the media, communications and the creative industries”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on Communications are: Lord Allen of Kensington Lord Hart of Chilton Baroness Benjamin Baroness Kidron Lord Best (Chairman) Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall Baroness Bonham-Carter of Yarnbury Baroness Quin The Earl of Caithness Lord Sheikh Bishop of Chelmsford Lord Sherborne of Didsbury Baroness Goldie Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords- interests Publications All publications of the Committee are available at: http://www.parliament.uk/hlcommunications Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at: http://www.parliamentlive.tv Further information Further information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is available at: http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords Committee staff The staff who worked on this inquiry were Anna Murphy (Clerk), Helena Peacock (Policy Analyst) and Rita Logan (Committee Assistant). Contact details All correspondence should be addressed to the Select Committee on Communications, Committee Office, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW. -

Annual Report 2006 Dear Stockholder, 2006 Has Been an Exciting Year of Transformation

07-4863-1_VirginMedia10K_Cover.qxp 13/4/07 22:43 Page 1 (CyanMagentaYellowBlack plate) plate) plate)plate) Annual Report 2006 Dear Stockholder, 2006 has been an exciting year of transformation. Our hard working and dedicated employees have created a leading entertainment and communications business. We now have the U.K.’s first “quad-play” offering of television, broadband, and home and mobile phone services under the Virgin Media brand. Virgin is one of the most recognized consumer brands in the world, and has fantastic recognition in the U.K. In March 2006, our predecessor company NTL Incorporated merged with Telewest Global Inc. combining the two largest U.K. cable operators. Our cable network now passes approximately 51% of U.K. households and we serve almost 5 million customers. The merger has delivered significant synergies by reducing operating and capital costs from the combined businesses. We have made major process improvements in our customer operations and IT and have completed the first major billing system migration, driving two-thirds of our customers to one system. This is already paying dividends in terms of cost savings, improved flexibility and customer care. In July 2006, we added mobile telephone services to our product offering with the acquisition of Virgin Mobile, a leading U.K. mobile virtual network operator with approximately 4.5 million mobile phone customers. We have since merged ourretail channels across our Mobile and Cable segments and introduced significant cross-sell activity with the launch of offers such as our 4 for £40 at the end of September. Concurrent with the acquisition of Virgin Mobile we also secured a brand license agreement with the Virgin Group to use the ‘Virgin’ brand. -

Transcript of the Media Plurality Roundtable Discussion

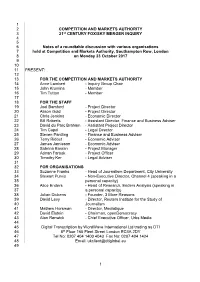

1 2 COMPETITION AND MARKETS AUTHORITY 3 21st CENTURY FOX/SKY MERGER INQUIRY 4 5 6 Notes of a roundtable discussion with various organisations 7 held at Competition and Markets Authority, Southampton Row, London 8 on Monday 23 October 2017 9 10 11 PRESENT: 12 13 FOR THE COMPETITION AND MARKETS AUTHORITY 14 Anne Lambert - Inquiry Group Chair 15 John Krumins - Member 16 Tim Tutton - Member 17 18 FOR THE STAFF 19 Joel Bamford - Project Director 20 Alison Gold - Project Director 21 Chris Jenkins - Economic Director 22 Bill Roberts - Assistant Director, Finance and Business Adviser 23 David du Parc Braham - Assistant Project Director 24 Tim Capel - Legal Director 25 Steven Pantling - Finance and Business Adviser 26 Terry Ridout - Economic Adviser 27 James Jamieson - Economic Adviser 28 Sabrina Basran - Project Manager 29 Adnan Farook - Project Officer 30 Timothy Ker - Legal Adviser 31 32 FOR ORGANISATIONS 33 Suzanne Franks - Head of Journalism Department, City University 34 Stewart Purvis - Non-Executive Director, Channel 4 (speaking in a 35 personal capacity) 36 Alice Enders - Head of Research, Enders Analysis (speaking in 37 a personal capacity) 38 Julian Dickens - Founder, 3 More Reasons 39 David Levy - Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of 40 Journalism 41 Mathew Horsman - Director, Mediatique 42 David Elstein - Chairman, openDemocracy 43 Alan Renwick - Chief Executive Officer, Urbs Media 44 45 Digital Transcription by WordWave International Ltd trading as DTI 46 8th Floor 165 Fleet Street London EC4A 2DY 47 Tel No: 0207 404 1400 4043 Fax No: 0207 404 1424 48 Email: [email protected] 49 1 1 THE CHAIR: Welcome to you today, and thank you very much for coming in today. -

The Price of Plurality

The Price of Plurality Choice, Diversity and Broadcasting Institutions in the Digital Age Edited by Tim Gardam and David A. L. Levy Published by Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Department of Politics and International Relations University of Oxford 13 Norham Gardens Oxford, OX2 6PS [email protected] Individual chapters Copyright © the respective authors of each chapter 2008 Editorial material and notes Copyright © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism of the University of Oxford 2008 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or disseminated or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, or otherwise used in any manner whatsoever without the express permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 978–0–95–588890–8 Edited by Tim Gardam and David A. L. Levy Cover design by Robin Roberts-Gant Layout and Print by Oxuniprint Contents Preface v Ed Richards Chief Executive, Ofcom The Structure and Purpose of This Book vii Tim Gardam and David Levy 1. The Purpose of Plurality 11 Tim Gardam 2. Does Plurality Need Protecting in the New Media Age? 23 2.1. Plurality and the Broadcasting Value Chain – Relevance and Risks? 25 Robin Foster 2.2. Lessons from the First Communications Act 36 David Puttnam 2.3. Plurality Preserved: Rethinking the Case for 41 Public Intervention in a New Media Market John Whittingdale 2.4. Public Purpose versus Pluralism? 46 Patricia Hodgson 2.5. Plurality: What Do We Mean by It? What Do We Want from It? 51 Simon Terrington and Matt Ashworth 3. -

Media Plurality Roundtable: Attendee List Monday 23 October, 2.00Pm – 5.00Pm

Media Plurality Roundtable: Attendee list Monday 23 October, 2.00pm – 5.00pm Attendees: Alan Renwick Dr Alice Enders David Elstein Dr David Levy Julian Dickens Mathew Horsman Professor Suzanne Franks Stewart Purvis Biographies: Alan Renwick – The CEO of Urbs Media, a tech-driven news agency. Alan has led corporate, venture-backed and start up media businesses. His previous posts include Head of Strategy at Local World Media, Client Director at Ocean Strategy and Business Development Director at TES Global. Dr Alice Enders – Alice Enders is Head of Research at Enders Analysis. She undertakes landmark research on the challenges and opportunities for creative industries in the digital age. Alice supplies consultancy services on music, licensing and B2B media. She is a former senior economist at the World Trade Organisation and was professor of economics at York University, Canada. Alice holds a doctorate in economics from Queens University, Canada. David Elstein - Chairman of Open Democracy and an executive producer at Portobello Films. Formerly worked on current affairs programmes for both the BBC and ITV (he was editor of Thames Television's This Week) before becoming a pioneering independent producer when Channel 4 launched. He then went to Thames as director of programmes, then worked as head of programmes for Sky Television before joining Channel 5 as chief executive a few months before its launch. Dr David Levy - Director of the Reuters Institute since September 2008. His work covers the full range of issues around developments in journalism and he has particular interests in public service broadcasting, media regulation and business models, and the interaction between digital technology and media regulation both within the UK and Europe. -

The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft David Elstein The political structure of UK broadcasting 1949-1999 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1247 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elstein, David: The political structure of UK broadcasting 1949-1999. Lüneburg: meson press 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1247. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14619/011 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 Attribution - Share Alike 4.0 License. For more information see: Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 David Elstein POLITICAL The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 STRUCTURE BROADCASTING UK ELSTEIN The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 Media, Democracy & Political Process Series Edited by Christian Herzog, Volker Grassmuck, Christian Heise and Orkan Torun The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 David Elstein Bibliographical Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche National bibliografie (German National Biblio graphy); detailed bibliographic information is available online at http://dnb.dnb.de Published in 2015 by meson press, -

The Future of Channel Four After the Broadcasting Act 1990

Irish Communication Review Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 5 January 1994 The Future of Channel Four After the Broadcasting Act 1990 Amanda Dunne Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation Dunne, Amanda (1994) "The Future of Channel Four After the Broadcasting Act 1990," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 5. doi:10.21427/D7RM7W Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol4/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License IRISH COMMUNICATIONS REVIEW VOL4 1994 Amanda Dunne has a The future of Channel Four after B.Sc. in Communications from Dublin Institute of Technology. She currently the Broadcasting Act 1990 lectures there. Amanda Dunne Introduction Television operates in the mutually-influencing realms of economics, politics and culture. Across Europe, huge changes have occurred at the indefinable point where culture and economics meet, and politics seeks to mediate or. more often, impose an agenda. This has brought about the deregulation of the television industry and, in its wake, re-regulation (Siune and McQuail 1992: 192, Silj l 992: 1 7). The resulting conflict has manifested itself most obviously in the clash of public service broadcasting and its commercial rivals.