Diversification of the Alberta Economy: in Search of Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta's Energy Future in Carbon Capture and Storage: a Comparative Analysis of CCS Legislation

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Master of Public Policy Capstone Projects 2013-09 Alberta's Energy Future in Carbon Capture and Storage: A Comparative Analysis of CCS Legislation Lancashire, Megan Lancashire, Megan. (2013). Alberta's Energy Future in Carbon Capture and Storage: A Comparative Analysis of CCS Legislation ( Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51616 report Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY CAPSTONE PROJECT Alberta’s Energy Future in Carbon Capture and Storage: A Comparative Analysis of CCS Legislation Submitted by: Megan Lancashire Approved by supervisor: Dr. Ken McKenzie Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of PPOL 623 and completion of the requirements for the Master of Public Policy degree Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 II. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 II.2 Carbon Capture and Storage: The Basics .................................................................................................. 5 II.3 The Carbon Capture and Storage Amendments Act, 2010 .................................................................... 8 II.4 Setbacks: The Economics of CCS Technology ................................................................................. -

Our Graduates

OUR GRADUATES FACULTY OF AGRICULTURAL, Mohsen Hashemiranjbar Sharifabad, Animal Science in Lisa Fox, Animal Science, Fairview LIFE AND ENVIRONMENTAL Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, Iran Yirui Gan, Crop Science, China SCIENCES Keisha Brittenay Hollman, Plant Science in Agricultural, Yiqing Gong, Agricultural and Resource Economics — Food and Nutritional Science, Sherwood Park Internship Program, China DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ziwei Hu, Agricultural and Resource Economics in Matthew John Guelly, Crop Science, Westlock Reza Ahmadi, Bioresource and Food Engineering in Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology, China Bradley Michael Hendricks, Crop Science, Strathmore Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, Edmonton Ashley Anne Hynes, Forest Biology and Management in Yiqing Huang, Animal Science, China Martha Carolina Archundia Herrera, Nutrition and Renewable Resources, Newfoundland Kira Lynne Kottke, Animal Science, Edmonton Metabolism in Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Ayesha Jain, Textiles and Clothing in Human Ecology, India Rebecca Esther Makepeace, Crop Science, Leduc County Science, Mexico Shiva Kiaras, Family Ecology and Practice in Human Matthew Ross McGillivray, Animal Science, Joseph Daniel Cooper, Forest Biology and Management in Ecology, Edmonton British Columbia Renewable Resources, United States Alvita Bertilla Mathias, Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Samuel Lane Nanninga, Crop Science, Barrhead Aidin Foroutan Naddafi, Animal Science in Agricultural, Science, India Erica Dawn Nelson, Crop Science, Rumsey -

Podium Alberta Recipients • 2017

Podium Alberta Recipients • 2017 Through Podium Alberta, Alberta Sport Connection is pleased to assist 249 athletes in 42 sports as they strive for Excellence in Sport. Alpine Skiing Cross Country Skiing Goalball Ski Cross Volleyball Jackson Leitch ^ Mark Arendz ^ Aron Ghebreyohannes ^ Zachary Belczyk Blair Bann Manuel Osborne-Paradis Ivan Babikov Tiana Knight ^ Mara Bishop Jay Blankenau Huston Philp Erik Carleton ^ Blair Nesbitt ^ Brady Leman Margaret Casault Trevor Philp Jesse Cockney Kristofor Mahler Jesse Elser Alana Ramsay ^ Reed Godfrey Gymnastics Abbey McEwen Pearson Eshenko Erik Read Devon Kershaw Damien Cachia Alexa Velcic Alexa Gray Jeffrey Read Graeme Killick Jackson Payne Ciara Hanly Kirk Schornstein ^ Christopher Klebl ^ Ski Jumping Jacob Kern Liam Wallace Julien Locke Brittany Rogers Kristen Moncks Tyler Werry Maya MacIsaac-Jones Keegan Soehn Taylor Henrich Jessica Niles Brian McKeever ^ Kyle Soehn Abigail Strate Brook Sedore Athletics Graham Nishikawa ^ Hockey Snowboard Leah Shevkenek Maria Bernard Derek Zaplotinsky ^ Danielle Smith Jennifer Brown ^ Karly Heffernan Carter Jarvis Lucas Van Berkel Kendra Clarke Curling Emerance Maschmeyer Christopher Robanske Rudy Verhoeff Isatu Fofanah Rachel Brown Meaghan Reid Joshua Reeves Graham Vigrass Elizabeth Gleadle Chelsea Carey Shannon Szabados Max Vriend Akeem Haynes Joanne Courtney Soccer Brett Walsh Alister McQueen ^ Dana Ferguson Sledge Hockey Stephanie Labbe Jessica O’Connell Marc Kennedy Zachary Lavin ^ Danica Wu Beach Volleyball Sage Watson Kevin Koe Zachary Moore-Savge -

Danielle Smith

Danielle Smith Danielle Smith hosts the Danielle Smith Show on NewsTalk770 in Calgary. As a University of Calgary graduate with degrees in Economics and English, Danielle has had a lifelong interest in Alberta public policy and finding the right balance between free enterprise and individual rights, and the role of government. Danielle’s public policy experience began with an internship at the Fraser Institute. She was also elected as a trustee for the Calgary board of education and served as the director of the Alberta Property Rights Initiative and the Canadian Property Rights Research Institute. She was also the director of provincial affairs for Alberta with the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. Most recently she was a Member of the Legislative Assembly for Highwood, leader of the Official Opposition, and leader of the Wildrose Party. Before entering politics, Danielle had extensive experience in the media. She was an editorial writer and columnist at the Calgary Herald for six years. She served as host of Global Sunday, a national current affairs television talk show, and was also the host of two programs on CKMX 1060 AM radio in Calgary, Health Frontiers and Standing Ground. She has made frequent guest appearances as a commentator on TV and radio. She married her husband, David Moretta in 2006 and is the proud stepmother of David’s son Jonathan. Danielle and David live in High River with their two dogs, Caine and Colt. Professional Highlights: • MLA for Highwood, 2012-2015 • Leader of the Official Opposition, 2012-2014 • Leader of the Wildrose Party, 2009-2014 • Canadian Federation of Independent Business, Alberta Director 2006-2009 • Editorial Writer and Columnist, Calgary Herald, 1999-2006 • TV Host, Global Sunday, 2003-2005 • Trustee, Calgary Board of Education, 1998-1999 • Managing Director, Canadian Property Rights Research Institute, 1997-1999 • Intern, Fraser Institute, 1996-1997 Academic Highlights: • Bachelor of Arts in Economics, University of Calgary (1997) • Bachelor of Arts in English, University of Calgary (1997) . -

Alberta Counsel Newsletter Issue 99 2020

THE ISSUE Alberta’s Premier Review of 99 NEWS Politics and Government Vitality JANUARY/2020 from UNPRECEDENTED DECADE IN ALBERTA POLITICS Jim Prentice, although victorious, renounced his seat right after the provincial election, sending Calgary Lougheed voters to the polls for the 3rd time in roughly one year. In the September 3, 2015 by-election they elected Prassad Panda of the COMES TO AN END Wildrose Party. Tragedy struck in the fall of 2015 with the unfortunate death of former Cabinet Minister Manmeet Bhullar. Robert Reynolds, Q.C. He was killed in a traffic accident on Highway 2 around Red Deer when he attempted to help a motorist during a snowstorm and was struck himself. His successor in Calgary-Greenway was Prab Gill who ran as a PC, but would ultimately become an Independent amidst accusations of participating in voter irregularity. How amazing were the 2010s in Alberta politics? The decade saw the demise of the Progressive Conservative Party, which had governed Alberta from 1971 – 2015. It saw the first NDP government in the province’s history, which also turned out to Undoubtedly the biggest political move during the period was the creation of the United Conservative Party (UCP) from the merger of the PC and Wildrose parties. Jason Kenney won the leadership by defeating Wildrose Leader Brian Jean and now Senior Editor: Pascal Ryffel be the only one-term government since Alberta entered Confederation and became a province in 1905. There were 6 Minister of Justice Doug Schweitzer. The resignation of long-time PC and then UCP MLA Dave Rodney led to Kenney Publisher: Alberta Counsel premiers in the decade (Stelmach, Redford, Hancock, Prentice, Notley and Kenney). -

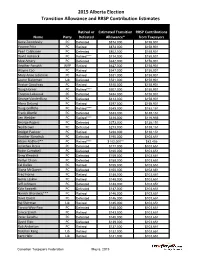

2015 Alberta Election Transition Allowance and RRSP Contribution Estimates

2015 Alberta Election Transition Allowance and RRSP Contribution Estimates Retired or Estimated Transition RRSP Contributions Name Party Defeated Allowance* from Taxpayers Gene Zwozdesky PC Defeated $874,000 $158,901 Yvonne Fritz PC Retired $873,000 $158,901 Pearl Calahasen PC Defeated $802,000 $158,901 David Hancock PC Retired**** $714,000 $158,901 Moe Amery PC Defeated $642,000 $158,901 Heather Forsyth WRP Retired $627,000 $158,901 Wayne Cao PC Retired $547,000 $158,901 Mary Anne Jablonski PC Retired $531,000 $158,901 Laurie Blakeman Lib Defeated $531,000 $158,901 Hector Goudreau PC Retired $515,000 $158,901 Doug Horner PC Retired**** $507,000 $158,901 Thomas Lukaszuk PC Defeated $484,000 $158,901 George VanderBurg PC Defeated $413,000 $158,901 Alana DeLong PC Retired $397,000 $158,901 Doug Griffiths PC Retired**** $349,000 $152,151 Frank Oberle PC Defeated $333,000 $138,151 Len Webber PC Retired**** $318,000 $116,956 George Rogers PC Defeated $273,000 $138,151 Neil Brown PC Defeated $273,000 $138,151 Bridget Pastoor PC Retired $238,000 $138,151 Heather Klimchuk PC Defeated $195,000 $103,651 Alison Redford** PC Retired**** $182,000** $82,456 Jonathan Denis PC Defeated $177,000 $103,651 Robin Campbell PC Defeated $160,000 $103,651 Greg Weadick PC Defeated $159,000 $103,651 Verlyn Olson PC Defeated $158,000 $103,651 Cal Dallas PC Retired $155,000 $103,651 Diana McQueen PC Defeated $150,000 $103,651 Fred Horne PC Retired $148,000 $103,651 Genia Leskiw PC Retired $148,000 $103,651 Jeff Johnson PC Defeated $148,000 $103,651 Kyle Fawcett -

Orange Chinook: Politics in the New Alberta

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2019-01 Orange Chinook: Politics in the New Alberta University of Calgary Press Bratt, D., Brownsey, K., Sutherland, R., & Taras, D. (2019). Orange Chinook: Politics in the New Alberta. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109864 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca ORANGE CHINOOK: Politics in the New Alberta Edited by Duane Bratt, Keith Brownsey, Richard Sutherland, and David Taras ISBN 978-1-77385-026-9 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

The Wildrose Alliance in Alberta Politics

SPP Research Papers Volume 4•Issue 6• May 2011 IS THIS THE END OF THE TORY DYNASTY? The Wildrose Alliance in Alberta Politics Anthony M. Sayers and David K. Stewart1 University of Calgary ABSTRACT The Alberta Tory dynasty begun by Peter Lougheed is now 40 years old. With only four leaders across four decades, the party has managed to maintain its hold on the political imagination of Albertans. It has weathered a number of storms, from minor party assaults during the tumultuous 1980s to the Liberal threat of 1993 and the stresses associated with the global financial crisis. Now it confronts a new challenge in the form of the Wildrose Alliance led by Danielle Smith. Just as the Tories stole the centre ground from beneath Social Credit in the 1970s, the Wildrose leadership team hopes to take what was a fringe right wing party and turn it into a broad coalition capable of appealing to a large number of Albertans. What challenges do they face in repositioning the party? And how will the Tories protect their home turf? In brief, the Wildrose Alliance must modify its policies and present them in such a manner as to be able to plausibly claim that it now reflects the core values of Albertans better than the current government. For its part, the government must select a new leader capable of successfully painting Wildrose as outsiders who cannot be trusted to cleave to the values that Albertans hold dear. What are these values? Strong support for individualism, a populist view of government – including wariness of the federal government – combined with a deep commitment to a role for government in providing core programs in areas such as health care, the environment, and social welfare. -

Manitoba Hockey History Bibliography

Manitoba Hockey Research Information Bibliography Note: Year of induction into the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame (MHHF) for individuals and teams is indicated in parentheses. George Allard, John McFarland, Ed Sweeney, Manitoba's Hockey Heritage: Manitoba Hockey Players Foundation, 1995 * ‐ Published to honour Manitoba 125 and the 10th anniversary of the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame. Includes biographies of Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame inductees. Biographies of those honoured in later years can be found on the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame Inc. website www.mbhockeyhalloffame.ca. Altona Maroons Reunion Committee, Celebrating 40 Years Altona Maroons 1951‐1991: Friesen, 1991 * ‐ Pictorial history of the Altona Maroons of the South Eastern Manitoba Hockey League. A supplement covering the fifth decade of the team was published for the Maroons' Homecoming, Aug. 3‐5, 2001. * Player, manager and team president Elmer Hildebrand was inducted into the MHHF as a builder in 2007. Kathleen Arnason, Falcons Gold: Canada's First Olympic Hockey Heroes: Coastline, 2002 * ‐ Juvenile novel based on the 1920 Winnipeg Falcons hockey team that was inducted into the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame in 1985. Illustrations by Luther Pokrant. Frank Frederickson (1985), Mike Goodman (1985), Fred (Steamer) Maxwell (1985), Wally Byron (1987) and Halldor (Slim) Halldorson (1987) are individual members of the MHHF. Richard Brignall, Forgotten Heroes Winnipeg's Hockey Heritage: J. Gordon Shillingford, 2011 * ‐ Manitoba's championship teams from the 1896 Stanley Cup winning Winnipeg Victorias to the province's last Memorial Cup champions, the 1959 Winnipeg Braves. All have been honoured by the MHHF. Brignall is a freelance writer based in Kenora, Ont. -

WCRR – Effects on Discovery Ridge

July 7, 2014 Danielle Smith, MLA, Highwood (Wildrose) Unit 5, 49 Elizabeth Street Box 568 Main Okotoks, AB Canada T1S 1A7 Phone: (403) 995-5488 [email protected] Dear Ms. Smith: RE: WEST CALGARY RING ROAD (WCRR) - EFFECTS ON DISCOVERY RIDGE / REQUEST FOR CONSULTATION I am writing you on behalf of the Discovery Ridge Community Association (DRCA). Discovery Ridge is a community of about 4300 residents in SW Calgary. The sole access to Discovery Ridge is from Provincial Highway 8 and the community has approximately 3.5 kilometers of highway frontage. Our residents will be significantly affected by the proposed West Calgary Ring Road (WCRR) and there is naturally a high degree of community interest. The DRCA is not opposed to the WCRR and we recognize the benefits of this major transportation investment to Calgarians and Albertans. We want to work with Alberta Transportation to make this a project we can all be proud of. We are, however, concerned about the current design concept and seeming insensitivity to the effects on adjacent properties, residents, and communities including Discovery Ridge. The current design does not sufficiently take into account adjacent context. Minimal consultation by Alberta Transportation has occurred; we are told that there will be no further opportunity for real community input; and that the final design will be left to the successful P3 firm. This is clearly unacceptable to DRCA - and seems to us to conflict with the Province’s commitment to transparency and collaboration with its citizens. The purpose of this letter is to therefore ask for your assistance in ensuring that proper contextually sensitive mitigation measures be included in the design of WCRR. -

Tax Reform in Canada Our Path to Greater Prosperity

About the Fraser Institute The Fraser Institute is an independent Canadian economic and social re- search and educational organization. It has as its objective the redirection of public attention to the role of competitive markets in providing for the well-being of Canadians. Where markets work, the Institute’s interest lies in trying to discover prospects for improvement. Where markets do not work, its interest lies in finding the reasons. Where competitive markets have been replaced by government control, the interest of the Institute lies in documenting objectively the nature of the improvement or deterioration resulting from government intervention. The Fraser Institute is a national, federally-chartered, non-profit organiza- tion financed by the sale of its publications and the tax-deductible contri- butions of its members, foundations, and other supporters; it receives no government funding. Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Armen Alchian Prof. J.M. Buchanan Prof. Jean-Pierre Centi Prof. Herbert G. Grubel Prof. Michael Parkin Prof. Friedrich Schneider Prof. L.B. Smith Sir Alan Walters Prof. Edwin G. West Senior Fellows Murray Allen, MD Prof. Eugene Beaulieu Dr. Paul Brantingham Prof. Barry Cooper Prof. Steve Easton Prof. Herb Emery Prof. Tom Flanagan Gordon Gibson Dr. Herbert Grubel Prof. Ron Kneebone Prof. Rainer Knopff Dr. Owen Lippert Prof. Ken McKenzie Prof. Jean-Luc Migue Prof. Lydia Miljan Dr. Filip Palda Prof. Chris Sarlo Adjunct Scholar Laura Jones Administration Executive Director, Michael Walker Director, Finance and Administration, Michael Hopkins Director, Alberta Policy Research Centre, Barry Cooper Director, Communications, Suzanne Walters Director, Development, Sherry Stein Director, Education Programs, Annabel Addington Director, Publication Production, J. -

I by © Michelle Irving a Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate

HOW DO PARTY LEADERS PRESENT THEMSELVES ON SOCIAL MEDIA? THE RACE FOR PREMIERSHIP IN WESTERN CANADIAN ELECTIONS 2011 - 2017 by © Michelle Irving A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Political Science/ Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences/ Dr. Amanda Bittner Memorial University of Newfoundland July 2019 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador i Abstract Voters have partisan and gendered expectations of candidates, and literature suggests that candidates will shape their campaigns to have wide appeal. It’s reasonable to expect that these decisions will extend beyond the “traditional” campaign to their social media presence, but we really do not know. I ask if candidates conform to traditional gendered stereotypes and how their self-presentation on social media is influenced by party label, sex, and electoral timeframe. I assess Twitter feeds of party leaders seeking the premiership in western Canadian elections. I analyze the use of gendered language in tweets to determine how, and in what ways, stereotypical norms impact a leaders’ self- presentation. My findings reveal that sex, party and time have an impact on tweets to varying degrees; with party label and time having the strongest overall effect. This analysis breaks down some complexities of self-presentation, furthering the dialogue around gender presentation in the political arena. ii Acknowledgements Thank you to my supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner for championing my project and for supporting my naïve idea that I could learn code in a matter of months. Your endless feedback on numerous garbage fire drafts has been invaluable; and knowing when not to provide feedback in order to push me forward and think through complex problems is even more appreciated.