Draft General Plan Document with Track Changes (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Chumash-Style Pictograph Sites in Fernandeño Territory

THREE CHUMASH-STYLE PICTOGRAPH SITES IN FERNANDEÑO TERRITORY ALBERT KNIGHT SANTA BARBARA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY There are three significant archaeology sites in the eastern Simi Hills that have an elaborate polychrome pictograph component. Numerous additional small loci of rock art and major midden deposits that are rich in artifacts also characterize these three sites. One of these sites, the “Burro Flats” site, has the most colorful, elaborate, and well-preserved pictographs in the region south of the Santa Clara River and west of the Los Angeles Basin and the San Fernando Valley. Almost all other painted rock art in this region consists of red-only paintings. During the pre-contact era, the eastern Simi Hills/west San Fernando Valley area was inhabited by a mix of Eastern Coastal Chumash and Fernandeño. The style of the paintings at the three sites (CA-VEN-1072, VEN-149, and LAN-357) is clearly the same as that found in Chumash territory. If the quantity and the quality of rock art are good indicators, then it is probable that these three sites were some of the most important ceremonial sites for the region. An examination of these sites has the potential to help us better understand this area of cultural interaction. This article discusses the polychrome rock art at the Burro Flats site (VEN-1072), the Lake Manor site (VEN-148/149), and the Chatsworth site (LAN-357). All three of these sites are located in rock shelters in the eastern Simi Hills. The Simi Hills are mostly located in southeast Ventura County, although the eastern end is in Los Angeles County (Figure 1). -

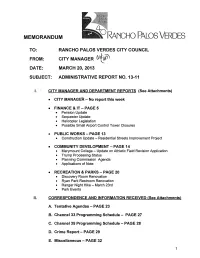

Administrative Report No. 13-11

~o MEMORANDUM . RANCHO PALOS VERDES TO: RANCHO PALOS VERDES CITY COUNCIL FROM: CITY MANAGER ~ DATE: MARCH 20, 2013 SUBJECT: ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT NO. 13-11 I.' CITY MANAGER AND DEPARTMENT REPORTS (See Attachments) • CITY MANAGE'R - No report this week • FINANCE & IT - PAGE 5 • Pension Update • Sequester Update • Helicopter Legislation • Possible Small Airport Control Tower Closures • PUBLIC WORKS - PAGE 13 • Construction Update - Residential Streets Improvement Project • COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT - PAGE 14 • Marymount College - Update on Athletic Field Revision Application • Trump Processing Status • Planning Commission Agenda • Applications of Note • RECREATION & PARKS - PAGE 20 • Discovery Room Renovation • Ryan Park Restroom Renovation • Ranger Night Hike - March 23rd • Park Events II. CORRESPONDENCE AND INFORMATION RECEIVED (See Attachments) A. Tentative Agendas - PAGE 23 B. Channel 33 Programming Schedule - PAGE 27 C. Channel 35 Programming Schedule - PAGE 28 D. Crime Report - PAGE 29 E. Miscellaneous - PAGE 32 1 March 2013 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 10:00 am-11:00 am-Meet & Greet wlAssembly Member 10:00 am-4:00 pm-Whale Muratsuchi @Katy Geissert ofaDay@PVIC Library in Torrance (Brooks) 6 4 5 6 7 8 9 7:30 am-Mayor's Breakfast 7:00 pm-City Council Meet- 7:00 pm-FACMeeting@ 6:00 pm-8:30pm - LCC @Coco's (BrookslKnight) ing@HessePark Community Room Membership Meeting@ LuminariaslMonterey Park (Campbell) ! 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 7:00 pm-Planning Commis- 7:00 pm-TSCPVDE Work- 6:00 pm----Salute to Business son Meeting@Hesse Park shop@ The -

Nursing Homes Targeted for High-Risk Pressure Ulcer And/Or Physical Restraint Improvement

National List: Nursing Homes Targeted for High-risk Pressure Ulcer and/or Physical Restraint Improvement Based on Quality Measure Scores as Calculated by CMS NOTE: For more information about CMS' quality measures for nursing homes, please visit the Nursing Home Compare tool at http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare. Targeted for Targeted for Improvement in Improvement in ZIP High-risk Name City County State Physical Code Pressure Ulcer Restraint Rates Rates X NHC HEALTHCARE, ANNISTON ANNISTON CALHOUN AL 36207 X CARE CENTER OF RED BAY RED BAY FRANKLIN AL 35582 X CIVIC CENTER HEALTH AND REHABI BIRMINGHAM JEFFERSON AL 35234 X CONSULTAMERICA COTTAGE HILLS PLEASANT GROVE JEFFERSON AL 35127 X FAIRFIELD NURSING AND REHABILITATION CENTER FAIRFIELD JEFFERSON AL 35064 X JEFFERSON REHAB & HEALTH CTR BIRMINGHAM JEFFERSON AL 35217 X OAK TRACE CARE & REHABILITATION CENTER BESSEMER JEFFERSON AL 35020 X SELF HEALTH CARE & REHAB CENTER INC HUEYTOWN JEFFERSON AL 35023 X SOUTH HEALTH AND REHABILITATIO BIRMINGHAM JEFFERSON AL 35205 X TERRACE OAKS CARE & REHABILITATION CENTER BESSEMER JEFFERSON AL 35021 X FLORENCE NURSING AND REHABILITATION CENTER FLORENCE LAUDERDALE AL 35630 X CARE CENTER OF OPELIKA OPELIKA LEE AL 36801 X PARKVIEW HEALTH CARE CENTER HUNTSVILLE MADISON AL 35810 X CITRONELLE CONVALESCENT CENTER CITRONELLE MOBILE AL 36522 X GRAND BAY CONVALESCENT HOME GRAND BAY MOBILE AL 36541 X CEDAR CREST MONTGOMERY MONTGOMERY AL 36116 X FATHER PURCELL MEMORIAL EXCEPTIONAL CHILDRENS CTR MONTGOMERY MONTGOMERY AL 36108 X FATHER WALTER MEMORIAL MONTGOMERY MONTGOMERY -

Michael Tseng Director of Planning

Michael Tseng Director of Planning Michael Tseng brings more than 20 years of retail design experience Education with an emphasis in planning and entitlements. Mr. Tseng skillfully leads the retail design team and oversees all coordination between Bachelor of Fine Arts, Interior Design the Client, Consultants and City Agencies. His expertise includes new Academy of Art University construction and renovation of regional lifestyle centers, neighborhood San Francisco, CA shopping centers and nationally recognized retail brands. His extensive knowledge of the entitlement process as well as his technical understanding of the construction document phase ensures his projects Affiliations are delivered successfully. International Council of Shopping Centers, Mr. Tseng’s communication skills underscore his ability to understand ICSC the Client’s needs ensuring the Client’s vision becomes reality. Always ahead of the curve on today’s trends, Mr. Tseng brings leading-edge retail Associate Member, American Institute of design principles to all his projects. Mr. Tseng’s design talent garnered Architects, AIA him a notable award by ENR’s, California Construction magazine in 2008 for Stoneridge Town Center. In addition, his commitment to high quality standards, design and technical excellence ensures his projects Contact deliver effective and profitable results for his Clients. 949.797.8370 [email protected] Selected Project Experience Retail Manhattan Village Mall Manhattan Beach, CA The Shops at LakePointe Deutsch Asset and Wealth Mgnt. Kirkland, WA Oakpointe Communities The Row Fresno, CA The District at Tustin Legacy Heritage Development Group Lastest Phase Tustin, CA * Peninsula Center Vestar Rolling Hill Estates, CA Vestar 49 Acres Walnut, CA * Village at Orange Sunjoint Development, LLC Orange, CA Vestar Sears Auto Center Conversion Carson, CA Mixed Use Seritage Retail Properties The Province Sears Auto Center Conversion San Gabriel, CA City of Industry, CA Chateau Operating Corp. -

3.5 Geology/Soils

3.5 GEOLOGY/SOILS 3.5.1 INTRODUCTION This section describes the project’s impacts related to geology and soils, including such factors as seismology, soils, topography, and erosion. It also includes an examination of potential hazards associated with potential damage to proposed structures and infrastructure from ground shaking, potential liquefaction hazards and soils and soils stability. Applicable laws, regulations and relevant local planning policies that pertain to geology are also discussed. Much of the information contained in this subsection was based upon the following geotechnical reports submitted by consultants under contract to the Chandler’s Palos Verdes Sand and Gravel Company and the peer review of those technical studies by Arroyo/Willdan Geotechnical: Geologic Constraints Investigation of the Chandler’s Inert Solid Land Fill Quarry and Surrounding Properties, Rolling Hills Estates, California, Earth Consultants International, June 15, 2000. Phase I Geologic and Geotechnical Engineering Study to Determine Potential Development Areas within the Chandler’s P.V. Sand and Gravel Company Property, Adjacent Trust Properties and the Rolling Hills Country Club, Rolling Hills Estates, California, Neblett & Associates, Inc., December 2001. Fault Investigation, Phases I and II, Chandler Quarry and Rolling Hills Country Club, Palos Verdes Estates, California, Neblett & Associates, Inc., April 29, 2005. Geotechnical Review, Geologic and Geotechnical Engineering Study, Potential Development Areas within the Chandler’s P.V. Sand and Gravel Company Property, Adjacent Trust Properties, and the Rolling Hills Country Club, City of Rolling Hills Estates, California, prepared by Arroyo Geotechnical, September 24, 2007. Review of Response Report, Geotechnical Review, Geologic and Geotechnical Engineering Study, Potential Development Areas within the Chandler’s P.V. -

1 the Volume of the Complete Palos Verdes Anticlinorium: Stratigraphic

The Volume of the Complete Palos Verdes Anticlinorium: Stratigraphic Horizons for the Community Fault Model Christopher Sorlien, Leonardo Seeber, Kris Broderick, Doug Wilson Figure 1: Faults, earthquakes, and locations. Lower hemisphere earthquake focal mechanisms, labeled by year, are from USGS and SCEC (1994), with location of 1930 earthquake (open circle) from Hauksson and Saldivar (1986). The surface or seafloor traces, or upper edges of blind faults are from the Southern California Earthquake Center Community Fault Model (Plesch and Shaw, 2002); other faults are from Sorlien et al. (2006). Figure 2 is located by red dashed polygon. L.A.=Los Angeles (downtown); LB=Long Beach (city and harbor); PVA=Palos Verdes anticlinorium, Peninsula and Hills, PVF=Palos Verdes fault; SPBF=San Pedro Basin fault; SMM=Santa Monica Mountains; SPS=San Pedro Shelf. Structural Setting If the water and post-Miocene sedimentary rocks were removed, the Los Angeles (L.A.) area would have huge relief, most of which was generated in the Plio-Pleistocene (Fig. 1; Wright, 1991). The five km-deep L.A. basin would be isolated from other basins to the SW by a major anticline-ridge, the Palos Verdes Anticlinorium (PVA), parallel to the current NW-SE coastline (Davis et al., 1989; Figures 2, 3). The Palos Verdes Hills have been long recognized as a contractional structure, but of dimensions similar to the peninsula (e.g., Woodring et al., 1946). This prominent topographic feature is instead only the exposed portion of the much larger PVA (Fig 2). Submerged parts of the PVA had previously been interpreted as separate anticlines (Nardin and Henyey, 1978; Legg et al., 2004) related in part to bends in strike-slip faults (Ward and Valensise, 1994), rather than a single complex structure above low-angle (oblique) thrust faults. -

Nature Walks

nature walks2017 nd 2 Saturdays january 14, 9 am White Point Nature Education Center & Preserve 1600 W Paseo Del Mar | San Pedro, CA 90731 | Tel: 310.561.0917 vicente bluffs reserve Hours: Wed, Sat & Sun 10 am - 4 pm Follow the bluff top from Family Nature Exploration: Every second Saturday (Free) 10 am Point Vicente to Oceanfront Third Wednesday Bird Walks: (Free-provided by Wild Birds Unlimited) 8:30 am Estates, an area containing Nature Walks with Naturalist: Every fourth Saturday (Free) 9 am restored coastal sage scrub Native Plant Sale: Every fourth Saturday 12 noon - 2 pm habitat. Great location for Workshops & Presentations: Different topic each month - For dates and to RSVP: pvplc.org sighting whales. Easy. RPV february 11, 3 pm George F Canyon Nature Center & Preserve 27305 Palos Verdes Drive East | Rolling Hills Estates, CA 90274 | Tel: 310.547.0862 sacred cove Hours: Fri 1- 4 pm; Sat & Sun 10 am - 4 pm Situated between First Saturday Family Hikes: Guided hikes through the canyon (Free) 9 am Portuguese Point and Fourth Wednesday Bird Walks: (Free-provided by Wild Birds Unlimited) 8:30 am Inspiration Point, this small Full Moon Hikes: Jan 13, Feb 10, Mar 12, Apr 9, May 7, June 9, July 8, Aug 6, Sep 3, Oct 6, cove features wonderful Nov 7, Dec 2. Must be age 9 and up ($12 person). For times and to RSVP: pvplc.org rock formations edged with tide pools and a channel into a sea cave. Strenuous. RPV june 10, 9 am october 14, 9 am Artists march 11, 2 pm alta vicente reserve lunada canyon white point/royal Explore 15-acre restoration Walk the trail in this quiet Plein air artists will be palms site with cactus wren neighborhood canyon in the painting on the preserves for the indicated walks. -

Rosett 1 Tectonic History of the Los Angeles Basin: Understanding What

Rosett 1 Tectonic history of the Los Angeles Basin: Understanding what formed and deforms the city of Los Angeles Anne Rosett The Los Angeles (LA) Basin is located in a tectonically complex region which has led to many, varying interpretations of its tectonic history. Current literature indicates that processes from rifting and extensional volcanism to pure dextral strike-slip displacement created the LA Basin. It appears that the best interpretation falls somewhere in between these two end-member explanations, with processes taking place simultaneously, including transtensional pull-apart faulting and clockwise rotation of large crustal blocks. With a comprehensive literature review, and paleomagnetic, seismic refraction, and low-fold reflection survey data, I intend to clarify what tectonic processes actually occurred in the LA Basin, and how that information can provide insight for other research in the region, as well as predicting future seismic hazards in the highly- populated, economically significant, and culturally rich city of Los Angeles. Introduction The Los Angeles Basin sits in a tectonically-active region, and thus, a large amount of research exists regarding its formation and tectonic history. However, due to several different fault systems, complex structures, and angles of slip currently affecting the area, the history of the LA Basin is not decisive; there are some discrepancies in the current literature regarding the tectonic and subsidence histories of the LA Basin. These include basin formation due to extensional rifting and basaltic volcanism (Crouch and Suppe, 1993; McCulloh and Beyer, 2003), transtensional pull-apart processes (Schneider et al., 1996), and dextral strike-slip faulting (Howard, 1996). -

Introduction I-1 Adopted by City Council 1/25/93

Introduction INTRODUCTION A. Overview of the City of Palmdale 1. Location and Regional Setting The City of Palmdale is located in the High Desert region of Los Angeles County, approximately 60 freeway miles north of downtown Los Angeles (see Exhibit I-1). Palmdale is one of two incorporated cities and several unincorporated communities within the Antelope Valley. The City is bordered by the City of Lancaster and unincorporated community of Quartz Hill to the north; unincorporated communities of Lake Los Angeles and Littlerock to the east; the unincorporated community of Acton to the south; and the unincorporated community of Leona Valley to the west (see Exhibit I- 2). The City of Palmdale Planning Area encompasses approximately 174 square miles within a transitional area between the foothills of the San Gabriel and Sierra Pelona Mountains and the Mojave Desert to the north and east (see Exhibit I-3). As a result, the Planning Area contains a variety of plant and animal communities, slope conditions, soil types and other physical characteristics. In general, the Planning Area slopes from south to north-northeast, with surface flows and subsurface flows trending away from the foothills to Rosamond Dry Lake. The major watercourses flowing through Palmdale are Amargosa Creek, Anaverde Creek, Little Rock Wash and Big Rock Wash. While foothill areas within and adjacent to the City contain significant slopes, a majority of the Planning Area is relatively flat. The climate of Palmdale and the Antelope Valley is dominated by the region’s Pacific high pressure system, which contributes to the area’s hot, dry summers and relatively mild winters. -

Groundwater Resources and Groundwater Quality

Chapter 7: Groundwater Resources and Groundwater Quality Chapter 7 1 Groundwater Resources and 2 Groundwater Quality 3 7.1 Introduction 4 This chapter describes groundwater resources and groundwater quality in the 5 Study Area, and potential changes that could occur as a result of implementing the 6 alternatives evaluated in this Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). 7 Implementation of the alternatives could affect groundwater resources through 8 potential changes in operation of the Central Valley Project (CVP) and State 9 Water Project (SWP) and ecosystem restoration. 10 7.2 Regulatory Environment and Compliance 11 Requirements 12 Potential actions that could be implemented under the alternatives evaluated in 13 this EIS could affect groundwater resources in the areas along the rivers impacted 14 by changes in the operations of CVP or SWP reservoirs and in the vicinity of and 15 lands served by CVP and SWP water supplies. Groundwater basins that may be 16 affected by implementation of the alternatives are in the Trinity River Region, 17 Central Valley Region, San Francisco Bay Area Region, Central Coast Region, 18 and Southern California Region. 19 Actions located on public agency lands or implemented, funded, or approved by 20 Federal and state agencies would need to be compliant with appropriate Federal 21 and state agency policies and regulations, as summarized in Chapter 4, Approach 22 to Environmental Analyses. 23 Several of the state policies and regulations described in Chapter 4 have resulted 24 in specific institutional and operational conditions in California groundwater 25 basins, including the basin adjudication process, California Statewide 26 Groundwater Elevation Monitoring Program (CASGEM), California Sustainable 27 Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), and local groundwater management 28 ordinances, as summarized below. -

1. NEOGENE TECTONICS of SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA . the Focus of This Research Project Is to Investigate the Timing of Rotation of T

1. NEOGENE TECTONICS OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA. The focus of this research project is to investigate the timing of rotation of the Transverse Ranges and the evolution of the 3-D architecture of the Los Angeles basin. Objectives are to understand better the seismicity of the region and the relationships between petroleum accumulations and the structure and stratigraphic evolution of the basin. Figure 1 shows the main physiographic and structural features of the Los Angeles basin region, the epicenter of recent significant earthquakes and the our initial study area in the northeastern Los Angeles basin. Los Angeles basin tectonic model: Most tectonic models attribute the opening of the Los Angeles basin to lithospheric extension produced by breakaway of the Western Transverse Ranges from the Peninsular Ranges and 90 degrees or more of clockwise rotation from ca. 18 Ma to the present. Evidence of this extension includes crustal thinning on tomographic profiles between the Santa Ana Mountains and the Santa Monica Mountains and the presence in the Los Angeles basin of Middle Miocene volcanic rocks and proto-normal faults. Detailed evidence of the 3-D architecture of the rift created by the breakaway and the timing of the rift phase has remained elusive. The closing of the Los Angeles basin in response to N-S contraction began at ca. 8 Ma and continues today (Bjorklund, et al., 2002). A system of active faults has developed that pose significant seismic hazards for the greater Los Angeles region. Crustal heterogeneities that developed during the extension phase of basin development may have strongly influenced the location of these faults. -

Initial Election Announcement

1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East II Initial Election Announcement 2013 Election of 1199SEIU Officers, Executive Council Members, Organizers and Delegates Announcement 2013 Election of 1199SEIU Officers, Executive Council Members, Organizers and Delegates This coming April 2013, the members of All petitioning locations will be open from 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East will 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on the first and last day again be electing our Union’s officers,* Executive of the petitioning period (Jan. 31, 2013 and Council members, organizers and, of course, Feb. 28, 2013). Delegates from each of our institutions. On a NY Region: Union-wide basis members will be voting for the Albany (155 Washington Avenue, Albany; Phone: offices of President, Secretary-Treasurer, sixteen (16) (518) 396-2300). Hicksville (100 Duffy Ave., Suite 3 Executive Vice Presidents, fourteen (14) Vice West, Hicksville; Phone: (516) 542-1115). Syracuse † Presidents at large and two (2) Organizers at large. (250 S. Clinton Street, Suite 200, Syracuse; Phone: In each of the fifty-nine (59) geographic/indus - (315) 424-1743). Rochester (259 Monroe Avenue, try-based Areas in our Union, members will elect Suite 220, Rochester; Phone: (585) 244-0830). North one (1) Area Vice President as well as at least one Country (95 E. Main St., Gouverneur; Phone: (315) (1) rank-and-file representative to the Union’s 287-9013). Buffalo (2421 Main Street, Buffalo; Executive Council (NY’s Home Care Areas A, B & C Phone: (716) 982-0540). White Plains (99 Church St., and Health System 7’s Central NY Area will have White Plains; Phone: (914) 993-6700).