OELMA Web.Version 11.08.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEXAS Library JOURNAL

TexasLibraryJournal VOLUME 88, NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2012 INCLUDES THE BUYERS GUIDE to TLA 2012 Exhibitors TLA MOBILE APP Also in this issue: Conference Overview, D-I-Y Remodeling, and Branding Your Professional Image new from texas Welcome to Utopia Notes from a Small Town By Karen Valby Last Launch Originally published by Spiegel Discovery, Endeavour, Atlantis and Grau and now available in By Dan Winters paperback with a new afterword Powerfully evoking the and reading group guide, this unquenchable American spirit highly acclaimed book takes us of exploration, award-winning into the richly complex life of a photographer Dan Winters small Texas town. chronicles the $15.00 paperback final launches of Discovery, Endeavour, and Atlantis in this stunning photographic tribute to America’s space Displaced Life in the Katrina Diaspora shuttle program. Edited by Lynn Weber and Lori Peek 85 color photos This moving ethnographic ac- $50.00 hardcover count of Hurricane Katrina sur- vivors rebuilding their lives away from the Gulf Coast inaugurates The Katrina Bookshelf, a new series of books that will probe the long-term consequences of Inequity in the Friedrichsburg America’s worst disaster. A Novel The Katrina Bookshelf, Kai Technopolis By Friedrich Armand Strubberg Race, Class, Gender, and the Digital Erikson, Series Editor Translated, annotated, and $24.95 paperback Divide in Austin illustrated by James C. Kearney $55.00 hardcover Edited by Joseph Straubhaar, First published in Jeremiah Germany in 1867, Spence, this fascinating Zeynep autobiographical Tufekci, and novel of German Iranians in Texas Roberta G. immigrants on Migration, Politics, and Ethnic Identity Lentz the antebellum By Mohsen M. -

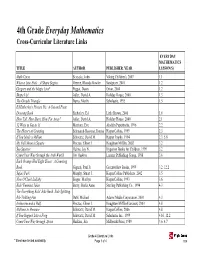

EM3 LIT Cross Cur Links Format 09-21-09 Sap

4th Grade Everyday Mathematics Cross-Curricular Literature Links EVERYDAY MATHEMATICS TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER, YEAR LESSON(S) Math Curse Scieszka, John Viking Children's, 2007 1.1 When a Line Ends…A Shape Begins Greene, Rhonda Gowler Sandpiper, 2001 1.2 Gregory and the Magic Line* Piggot, Dawn Orion, 2004 1.2 Shape Up! Adler, David A. Holiday House, 2000 1.3 The Greedy Triangle Burns, Marily Scholastic, 1995 1.5 Ed Emberley's Picture Pie: A Cut and Paste Drawing Book Emberley, Ed Little Brown, 2006 1.6 How Tall, How Short, How Far Away? Adler, David A. Holiday House, 2000 2.1 12 Ways to Get to 11 Merriam, Eve Aladdin Paperbacks, 1996 2.2 The History of Counting Schmandt-Besserat, Denise HarperCollins, 1999 2.3 If You Made a Million Schwartz, David M. HarperTrophy, 1994 2.3, 5.8 My Full Moon is Square Pinczes, Elinor J. Houghton Mifflin, 2002 3.2 Sea Squares Hulme, Joy N. Hyperion Books for Children, 1999 3.2 Count Your Way through the Arab World Jim Haskins Lerener Publishing Group, 1988 3.6 Each Orange Had Eight Slices: A Counting Book Giganti, Paul Jr. Greenwillow Books, 1999 3.2, 12.2 Safari Park Murphy, Stuart J. HarperCollins Publishers, 2002 3.5 Nine O'Clock Lullaby Singer, Marilyn HarperCollins, 1993 3.6 Kids' Funniest Jokes Barry, Shelia Anne Sterling Publishing Co., 1994 4.3 The Everything Kids' Joke Book: Side-Splitting, Rib-Tickling Fun Dahl, Michael Adams Media Corporation, 2001 4.3 Inchworm and a Half Pinczes, Elinor J. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003 4.8 Millions to Measure Schwartz, David M. -

An Alpha-Number-Bet Event Kit

An Alpha-number-bet Event Kit by TINY DiTERLOONEY Dear Bookseller, Teacher, or Librarian, Welcome to G is for One Gzonk! A book thought up by me. I am the author and artist (as soon you’ll plainly see) of an alphabet of creachlings! A twenty-six-letter menagerie! But I must confess, as you may have guessed, It won’t teach you A, B, C. Angry Acks, blue Bloobytacks, and Cootie Noodles dwell within these pages. And activities based on numbers and letters for kids of all ages! W ITHIN THIS EVENT KIT, YOU WILL FIND: • Twenty-seventh Letter of the Alphabet • Bloobytack Memory • Who’s the Hoofle-Foofle? • Mighty Mee-Yighty Maze • Yellow Yummel-Yum Puzzles • G is for One Gzonk Silly Straws giveaway • G is for One Gzonk Name Tag stickers • Answer Key So enjoy, have fun, And let yourself be silly! Until we meet again, Tiny DiTerlooney (a.k.a. Tony DiTerlizzi) a.k.a. means “also known as” G is for One Gzonk! ISBN-13: 978-0-689-85290-9 ISBN-10: 0-689-85290-8 $16.95/$19.95 CAN Release date: 9/12/06 G is for One Gzonk! Flash Cards Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers ISBN-13: 978-1-4169-4115-6 Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing ISBN-10: 1-4169-4115-0 $12.99/$16.99 CAN www.SimonSaysKids.com • www.diterlizzi.com Release date: 10/16/06 REPRODUCIBLE Illustrations © 2006 by Tony DiTerlizzi by TINY DiTERLOONEY SUGGESTED EVENT SCHEDULE 672 hours ahead (or one month ahead) • Pick a date and time for your event. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-09553 CBS CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 51 W. 52nd Street New York, NY 10019 (212) 975-4321 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant's principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange 7.625% Senior Debentures due 2016 American Stock Exchange 7.25% Senior Notes due 2051 New York Stock Exchange 6.75% Senior Notes due 2056 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933). Yes ☒ No o Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

Literature List

Literature List for Grades 1–3 Your child will enjoy reading literature related to mathematics at home. Many of these titles can be found at your local library. Number Patterns and Counting Pattern Bugs 12 Ways to Get to 11 Trudy Harris Eve Merriam The Millbrook Press, 2001 Aladdin Paperbacks, 1996 Pizza Counting 26 Letters and 99 Cents Christina Dobson Tana Hoban Charlesbridge, 2002 Greenwillow Books, 1991 Six Foolish Fishermen Arctic Fives Arrive Daniel San Souci Elinor J. Pinczes Hyperion, 2000 Houghton Mifflin, 1996 Twenty Is Too Many Can You Count Ten Toes?: Count to Kate Duke 10 in 10 Different Languages Dutton Children’s Books, 2000 Lezlie Evans Two Ways to Count to Ten: Houghton Mifflin, 2004 A Liberian Folktale City by Numbers Ruby Dee Stephen T. Johnson Henry Holt and Company, 1988 Viking, 1999 What’s a Pair? What’s a Dozen? Each Orange Had 8 Slices Stephen R. Swinburne Paul Giganti Boyds Mills Press, 2000 HarperTrophy, 1999 Number Stories and Operations Less Than Zero Amanda Bean’s Amazing Dream Stuart J. Murphy Cindy Neuschwander Copyright © Wright Group/McGraw-Hill HarperTrophy, 2003 Scholastic, 1998 Math for All Seasons Anno’s Mysterious Multiplying Jar Greg Tang Masaichiro Anno Scholastic, 2002 HarperTrophy, 1986 Missing Mittens Bats on Parade Stuart J. Murphy Kathi Appelt HarperCollins Publishers, 2001 HarperCollins Publishers, 1999 One Hundred Ways to Get to 100 The Best of Times Jerry Pallotta Greg Tang Scholastic, 2003 Scholastic, 2002 54 Home Connection Handbook The Doorbell Rang Two of Everything: Pat Hutchins A Chinese Folktale Greenwillow Books, 1986 Lily Toy Hong Albert Whitman & Co., 1993 Equal Shmequal Virginia Kroll The Warlord’s Beads Charlesbridge, 2005 Virginia Walton Pilegard Pelican, 2001 The Grapes of Math Greg Tang Place Value Scholastic, 2001 Anno’s Counting Book The Great Divide: Mitsumasa Anno A Mathematical Marathon HarperTrophy, 1986 Dayle Ann Dodds Can You Count to a Googol? Candlewick, 2005 Robert E. -

For Immediate Release: March 23, 2010

S I M O N & S C H U S T E R CHILDREN'S PUBLISHING DIVISION 1230 Avenue of the Americas Anna McKean New York, NY 10020 212-698-1135 • Fax: 212-698-4350 [email protected] For Immediate Release: March 23, 2010 Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Participates in OfficeMax Cause Program to Support Teachers Simon & Schuster Supplies Children’s Authors to join in OfficeMax’s Surprise Teacher Visits Nationwide Naperville, Ill. – OfficeMax® (NYSE: OMX), a leader in office products and services, and Simon & Schuster‟s Children‟s Publishing will make some lucky teachers‟ days this year by surprising them with classroom supplies and a visit from a popular children‟s book author. On behalf of OfficeMax‟s “A Day Made Better” cause, the companies plan to surprise extraordinary teachers at Title 1 schools with more than $1,000 in school supplies presented by local OfficeMax associates and accomplished children‟s literary authors. Simon & Schuster first participated in the cause in October 2009 and has selected to expand its involvement in 2010 to call attention to the issue of teacher-funded classrooms and encourage support for teachers nationwide. “We‟re pleased to have the support of Simon & Schuster‟s Children‟s Publishing to help raise awareness and generate widespread support for teachers nationwide,” said Bob Thacker, senior vice president of marketing and advertising for OfficeMax. “We are deeply committed to supporting teachers and their classrooms and are excited to include renowned children‟s authors in our classroom surprises.” Simon & Schuster‟s 2009 participating authors included Mac Barnett, author of The Brixton Brothers series, Sarah Rees Brennan, author of The Demon‟s Lexicon trilogy, Jon Scieszka, author of the SPHDZ and Trucktown series, and Scott Westerfeld, author of Leviathan. -

Travel the Usa: a Reading Roadtrip Booklist

READING ROADTRIP USA TRAVEL THE USA: A READING ROADTRIP BOOKLIST Prepared by Maureen Roberts Enoch Pratt Free Library ALABAMA Giovanni, Nikki. Rosa. New York: Henry Holt, 2005. This title describes the story of Alabama native Rosa Parks and her courageous act of defiance. (Ages 5+) Johnson, Angela. Bird. New York: Dial Books, 2004. Devastated by the loss of a second father, thirteen-year-old Bird follows her stepfather from Cleveland to Alabama in hopes of convincing him to come home, and along the way helps two boys cope with their difficulties. (10-13) Hamilton, Virginia. When Birds Could Talk and Bats Could Sing: the Adventures of Bruh Sparrow, Sis Wren and Their Friends. New York: Blue Sky Press, 1996. A collection of stories, featuring sparrows, jays, buzzards, and bats, based on African American tales originally written down by Martha Young on her father's plantation in Alabama after the Civil War. (7-10) McKissack, Patricia. Run Away Home. New York: Scholastic, 1997. In 1886 in Alabama, an eleven-year-old African American girl and her family befriend and give refuge to a runaway Apache boy. (9-12) Mandel, Peter. Say Hey!: a Song of Willie Mays. New York: Hyperion Books for Young Children, 2000. Rhyming text tells the story of Willie Mays, from his childhood in Alabama to his triumphs in baseball and his acquisition of the nickname the "Say Hey Kid." (4-8) Ray, Delia. Singing Hands. New York: Clarion Books, 2006. In the late 1940s, twelve-year-old Gussie, a minister's daughter, learns the definition of integrity while helping with a celebration at the Alabama School for the Deaf--her punishment for misdeeds against her deaf parents and their boarders. -

2004 Popular Paperbacks

2004 Popular Paperbacks The Popular Paperbacks for Young Adults Committee, sponsored by the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) of the American Library Association (ALA), announced its 2004 selections finalized at the ALA Midwinter Meeting, held January 9-12 in San Diego. This year’s committee produced four lists of selected titles. This year’s lists are: ; ; ; and . If It Weren’t For Them: Heroes. Heroes are everywhere. They are real and imaginary, historic and contemporary. Chair Andrea Milano remarked, “We hope these books will inspire teens to find heroes in their world.” On That Note…Music and Musicians. The list, which features fiction and non-fiction, encompasses a wide range of musical styles including classical, country, blues, rock, rap, and hip-hop. There are few titles for mature teens; however, most will appeal to teens of all ages. “In the age of Britney and Christina, we wanted to offer alternatives to tabloid-style tell-all biographies,” said chair Tricia Suellentrop. Guess Again: Mystery and Suspense. Traditional whodunits, fast-paced non-fiction, and nail biters make this a sure-fire mix that teens will love. “Whether you want them turning pages or developing their power of deduction, there’s nothing better than a good mystery,” said interim chair Walter M. Mayes. Simply Science Fiction is a list that begs us to ask “what if.” This exciting group of books explores the fascinating possibilities of our future. Chair Lynn Rutan wanted to comment but was late for her spaceship leaving for Mars. Committee chair, Michael G. Pawuk, had this to say about this year’s lists: “If you’re a teen looking for a time-tested favorite or for an exciting new read to a library looking for fun and wide-ranging genre lists, I feel confident that these lists have much to offer.” The members of the 2004 Popular Paperbacks for Young Adults committee are: Michael G. -

United Technologies / Viacom Letter Re

233503 April 21,2005 via Federal Express Mr. Brad W. Bradley EPA Project Coordinator U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region V, Mailcode SR-6J 77 W. Jackson Boulevard Chicago, IL 60604 W Re: In the Matter of Little Mississinewa Site CERCLA Docket No. V-W-'05-C-812 Dear Mr. Bradley: I. Introduction On or about April 4, 2005, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region V ("EPA"), issued an Administrative Order for Remedial Action (Docket No. V-W-'05-C-812) (the "Order" or "Unilateral Order") to Viacom Inc. ("Viacom") and United Technologies Corporation on behalf of Lear Corporation Automotive Systems ("UTC") (collectively, "Respondents"), directing those parties to implement the approved remedial design for the Little Mississinewa Site in Union , City, Indiana (the "Site"). The purposes of this letter are: (1) to advise EPA, pursuant to Section XXIV of the Order, of Respondents' intention to comply with the terms of the Order to the extent such compliance is required under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act ("CERCLA"), 42 U.S.C. §§9601, et seq., and its implementing regulations, namely the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan ("NCP"), 40 C.F.R. Part 300; and (2) to outline several objections and defenses that Respondents have to the Order, as issued. II. General Objections and Reservation of Rights As an initial matter, it should be noted that by setting forth any objections or defenses in this letter, or by submitting this letter at all, Respondents do not waive, and hereby specifically reserve their rights to raise additional or different objections and defenses to the Order at some later time, or to provide additional information and evidence in support of any position that they may respectively or collectively take in Mr. -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won. -

SCBWI New England

September - October 2014 the society of children’s book writers illustrators New EnglandN& ews NESCBWI representatives at the Upcoming NESCBWI Events LA Summer conference in August. September 25 Read about it inside! “Creating Cross-cultural Books” Free - register at [email protected] Stacy Mozer, Assisitant September 27 (9:00 am – 4:00 pm), Encore! Regional Advisor & Critique Group Coordinator 2014, Rhode Island College, Providence RI. Kathy Quimby Johnson, Co-Regional Advisor Sold out! Denise Ortakales, Co-Illustrator Coordinator NESCBWI 2015 Conference April 24-26, 2015! 1 What’s Inside! The Society of Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators New England Who’s Who page 2 NESCBWI Resources page 3 The LA Story - the Summer Conference page 4 Updated Market Report page 6 The James Marshall Fellowship Inspires page 11 Mamber News page 12 Updated Critique Groups page 15 The Society of Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators New England Who’s Who Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/nescbwi NESCBWI C0-Regional Advisors Conference Directors [email protected] At-large & Conference Director Marilyn Salerno [email protected] Kristine C. Asselin 2013-14 19 Francine Drive Holliston, MA 01746 Natasha Sass 2014-15 Marilyn Salerno Co-Regional Advisor Southern NE (CT, RI) Sally Riley [email protected] Email List Organizer Sally Riley Central NE (MA) [email protected] Margo Lemieux [email protected] New England Illustrator Coordinators Northern NE (ME, NH, VT) Denise Ortakales Kathy Quimby Johnson Ruth Sanderson [email protected] NEWS Staff Assistant Regional Advisor Editor-in-Chief J. L. Bell [email protected] Margo Lemieux Box 583 Assistant Regional Advisor & Critique Group Mansfield, MA 02048 Coordinator Stacy [email protected] Market News Editor J. -

Reading Rules! Motivating Teens to Read

Reading Rules! This Page Intentionally Left Blank Reading Rules! Motivating Teens to Read Elizabeth Knowles Martha Smith 2001 Libraries Unlimited, Inc. Englewood, Colorado Copyright © 2001 Elizabeth Knowles and Martha Smith All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. P.O. Box 6633 Englewood, CO 80155-6633 1-800-237-6124 www.lu.com ISBN 1-56308-883-5 Contents CONTENTSContents 1—THE INTRODUCTION/SITUATION .....................1 Annotated Professional Journal Articles ....................2 Annotated Professional Books .........................4 2—THE PROBLEM .............................5 Annotated Professional Journal Articles ....................6 3—THE SOLUTIONS ...............................9 Annotated Professional Journal Article....................11 Annotated Professional Books ........................11 4—THE READING ENVIRONMENT ......................13 Professional Discussion Questions ......................13 Practical Application .............................14 Brain-Centered Environment Basics ..................14 Middle School Media Center Advisory Panel ..............14 Checklist for Evaluating the Media Center ...............15 Sample Curriculum Displays ......................15 Reader’s Survey.............................17 Teacher’s Survey ............................18