The Changing Roles of Female Visual Artists in Morocco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royaume Du Maroc Ministère De La Culture

Royaume du Maroc Ministère de la Culture 995L - 581 - 43 - 8 Itinéraire Nuit des 2 1 Galeries 2012 3 N° sur le Nom de la Galerie plan 1 Mohammed El Fassi 2 Théâtre Med V 4 3 Bank Al-Maghrib 5 Institut français 7 4 6 5 Marsam 6 Caisse de Dépôt et de Gestion (Espace CDG) 7 Abou Inane (Groupe Crédit Agricole) 8 Bab Rouah 9 Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc (BNRM). 8 Participent à la Septième Edition de la Nuit des Galeries : Agadir rAtelier Arenciel Av 29 février N°55 Talborjt, Agadir . Tél. 0661 73 16 55, [email protected] rLe Sous Sol Art Gallery Imm, achar angle Av. 29 février, Av. Kennedy, Talborjt – Agadir. Tél.0528 84 48 49/ 0661 13 29 47, [email protected] Assilah rAplanos Gallery 89 rue Tijara, Assilah (Medina). Tél. 0666 99 80 30, [email protected] rGalerie du Centre Hassan II des Rencontres Internationales- forum Assilah Centre Hassan II des Rencontres Internationales. Tél. 05 37 70 37 07 / 05 37 70 38 09, [email protected] rGalerie les Amis de Hakim Place Sidi Benaissa, n°14, ancienne ville, Assilah. Tél. 0661 79 95 35, [email protected] rMaison de l’Art Contemporain d’Assilah Plage de Akwas Briech Assilah. Tél. 06 61 46 06 48, [email protected] Azemmour rMaison de l’art contemporain Mazagan d’Azemmour Ancienne Medina, Azemmour. Tél. 06 61 46 06 48, [email protected] Casablanca rAlif Ba 46, rue Omar Slaoui 20140 – Casablanca. Tel.: +212 5 22 20 97 63 - Fax: +212 5 22 27 39 12. -

JGI V. 14, N. 2

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 14 Number 2 Multicultural Morocco Article 1 11-15-2019 Full Issue - JGI v. 14, n. 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation (2019) "Full Issue - JGI v. 14, n. 2," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol14/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multicultural Morocco JOURNAL of GLOBAL INITIATIVES POLICY, PEDAGOGY, PERSPECTIVE 2019 VOLUME 14 NUMBER 2 Journal of global Initiatives Vol. 14, No. 2, 2019, pp.1-28. The Year of Morocco: An Introduction Dan Paracka Marking the 35th anniversary of Kennesaw State University’s award-winning Annual Country Study Program, the 2018-19 academic year focused on Morocco and consisted of 22 distinct educational events, with over 1,700 people in attendance. It also featured an interdisciplinary team-taught Year of Morocco (YoM) course that included a study abroad experience to Morocco (March 28-April 7, 2019), an academic conference on “Gender, Identity, and Youth Empowerment in Morocco” (March 15-16, 2019), and this dedicated special issue of the Journal of Global Initiatives. Most events were organized through six different College Spotlights titled: The Taste of Morocco; Experiencing Moroccan Visual Arts; Multiple Literacies in Morocco; Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development Challenges in Morocco, Moroccan Cultural Festival; and Moroccan Solar Tree. -

Lundi 28 Décembre 2015 À 16 H 30 - Hôtel Sofitel - Marrakech

Lundi 28 Décembre 2015 à 16 h 30 - Hôtel Sofitel - Marrakech Ventes aux enchères Lundi 28 Décembre 2015 à 16 h 30 HOTEL SOFITEL - MARRAKECH Art Moderne et Contemporain Peinture Marocaine - Peinture Orientaliste Photographie Président Fondateur Chokri Bentaouit Commissaire Priseur Maître Alexandre Millon - Maison Millon - Paris Expositions publiques Samedi 26 - De 10 h à 20 h Dimanche 27 - De 10 h à 20 h Lundi 28 - De 10 h à 14 h 6, Rue Khalil Metrane - 90000 -Tanger Tel / Fax : +212 539 37 57 07 +212 661 19 73 31 [email protected] www.mazadart.com Editeur : Mazad et Art Conception graphique : Mazad et Art Impression : Europrint Crédit Photos : Rachid Ouettassi Photo : Abdelmohcine nakari Impression directe sur ForexP. 2 120 x 80 cm Mazad et art , maison de vente aux enchères de tableaux et objets d’arts organise sa vente D’hiver comme a son accoutumé a l’hôtel Sofitel Marrakech et ce le 28 décembre 2015 à 17 h. Pour ne pas faillir a ses habitudes caritatives ou éducatives , Mazad met en vente un portfolio de 12 photographies qui permettra au futur acquéreur non seulement une acquisition importante de photographies , mais aussi de soutenir le programme éducatif du musée de la photographie et des arts visuels de Marrakech. Durant cette vente , seront proposés plusieurs tableaux et objets d’arts dont une sculpture de Ahmed Benyessef très rare offerte aux hommes de paix dans le monde par les Nations Unis. Sera mise en vente aussi pour la première fois une voiture de collection : Une mercedes PONTON 180 (1962) . Toujours dans le souci d’élargir les produits de collection, nous avons pu trouver un coffre rifain unique du 18 ème très recherché pour le plus grand bonheur de nos collectionneurs. -

Bibliothèque Le Cube

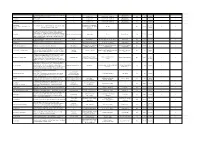

titre de l'exposition artistes curateur auteurs lieu de l'exposition éditeurs nombre de pages année langue exposition d'artistes marocains nombre d'exemplaires Villa Delaporte / Fouad Bellamine, Mahi Binebine, Mustapha Boujemaoui, James Brown, Safâa Erruas, Sâad Hassani, Aziz Lazrak / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français x 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Après la pluie Pierre Gangloff / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 52p 2011 français 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Jacques Barry Angel For Ever / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français 1 art contemporains Yusur-Puentes espagnol - Paysage et architecture au Maroc et en Emilia Hernández Pezzi, Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya, Ainhoa Díez de Pablo, El Montacir Bensaïd, Iman Benkirane. Programmation culturelle de la Présidence espagnole de l’Union européenne Madrid 62p 2010 x 1 français Espagne Chourouk Hriech, Fouad Bellamine, Azzedine Baddou, Hassan Darsi, Ymane Fakhir, Faisal Samra, Fatiha Zemmouri, Mohamed Arejdal, Mohamed El Baz, Philippe Délis, Saad Tazi, Younes Baba Ali, Between Walls Abdelmalek Alaoui, Yasmina Naji Yasmina Naji Rabat Integral Editions 44p 2012 français x 1 Amande In, Anna Raimondo, Mohammed Fettaka, Ymane Fakhir, Mustapha Akrim, Hassan Ajjaj, Hassan Slaoui, Mohamed Laouli, Mounat Charrat, Tarik Oualalou, Fadila El Gadi Regards Nomades Mohamed Abdel Benyaich, Hassan Darsi, Mounir Fatmi, Younes Rahmoun, Batoul S'Himi Anne Dary Frédéric Bouglé Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole - France Ville de Dole 42p 1999 français -

Le Prix Du Vaccin Entre Supputations Et Démentis

La Jordanie va ouvrir un Consulat général à Laâyoune S.M Mohammed VI s'entretient par téléphone avec S.M le Roi Abdallah II Ibn Al Hussein Lire Page 2 www.libe.ma ibération L Prix: 4 DH N°: 9171 Samedi/Dimanche 21-22 Novembre 2020 Directeur de Publication et de la Rédaction : Mohamed Benarbia Le Maroc demande à l'UA de lutter contre le séparatisme et la militarisation des Le prix du vaccin milices en Afrique entre supputations et démentis Manœuvres algériennes pour torpiller la démocratie au sein De petits malins ont fixé un tarif que le ministère de la Santé réfute du Parlement panafricain Page 5 Refoulement à chaud des migrants irréguliers L’Espagne a désormais les mains libres Page 6 Une issue plus ou moins satisfaisante pour les joueurs du Raja Les primes de matches déboursées en attendant le reste Lire page 8 Page 30 2 LIBÉRATION SAM/DIM 21-22 NOVEMBRE 2020 La Jordanie va ouvrir un Consulat général à Laâyoune Le Président sénégalais S.M Mohammed VI s'entretient par téléphone salue le sens de la mesure avec S.M le Roi Abdallah II Ibn Al Hussein dont le Maroc a fait preuve é e Président de la République du Sénégal, Macky Sall, a salué ''le sens de la mesure et de la t L retenue" dont le Royaume du Maroc fait preuve, en vue de maintenir la sta- i bilité de la zone tampon de Guergua- rat. l "Dans l’esprit de sa position tra- ditionnelle sur ce dossier, le Sénégal réitère son soutien au Royaume du Maroc dans la défense de ses droits a légitimes", écrit le Président Macky Sall dans un message adressé à Sa Majesté le Roi Mohammed VI. -

Présentation-Fondation-Alliances

UNE FONDATION RÉSOLUMENT ENGAGÉE DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT CULTUREL Présentation janvier 2018 SOMMAIRE . HISTORIQUE . LCC PROGRAM : POUR LE SOUTIEN DE LA CRÉATION ÉMERGENTE . PASSERELLES : SENSIBILISER AUX ARTS VISUELS . MACAAL : UN ÉCRIN POUR LA CRÉATION CONTEMPORAINE AFRICAINE . UN PARC DE SCULPTURES MONUMENTALES AU PIED DE L’ATLAS . MÉCÉNAT CULTUREL : UN SOUTIEN INDÉFECTIBLE AUX MANIFESTATIONS ARTISTIQUES DU CONTINENT . UNE ÉQUIPE PASSIONNÉE ET DYNAMIQUE . BILAN DES ACTIONS UNE FONDATION RÉSOLUMENT ENGAGÉE DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT CULTUREL Créée en 2009, la Fondation Alliances est une association à but non lucratif ayant pour vocation d’accompagner le développement culturel du Royaume du Maroc par le lancement de programmes phares, avec l’appui de réseaux d’experts. Par le développement d’un projet muséographique (MACAAL), d’un Parc de Sculptures monumentales, de programmes de soutien à la photographie africaine émergente (La Chambre Claire - Lcc Program) et de sensibilisation à l’art contemporain (Passerelles), la Fondation Alliances favorise l’accès de larges publics au champ culturel. Elle défend l’idée d’un art accessible à tous en développant une médiation culturelle importante en faveur de tous les milieux sociaux et participe ainsi au rayonnement de l’art contemporain marocain et africain à travers une approche exigeante. FONDATION ALLIANCES PROGRAMME BIANNUEL DE SOUTIEN À LA PHOTOGRAPHIE AFRICAINE ÉMERGENTE . Production de l’exposition individuelle du lauréat . Visibilité offerte à l’ensemble des participants (dispositif digital offrant un espace dédié) . Jury de professionnels de la culture . Mise en réseau de la communauté de photographes du LCC Program auprès des institutions et manifestations culturelles locales et internationales . Édition de catalogues / book FONDATION ALLIANCES Historique et évolution Lancée en 2013, La Chambre Claire est un rendez-vous biannuel destiné à soutenir la photographie africaine émergente. -

Bibliothèque Le Cube.Xlsx

titre de l'exposition artistes curateurs auteurs lieu de l'exposition éditeurs nombre de pages année langue exposition d'artistes marocains nombre d'exemplaires Fouad Bellamine, Mahi Binebine, Mustapha Boujemaoui, James Brown, Villa Delaporte / / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français x 1 Safâa Erruas, Sâad Hassani, Aziz Lazrak art contemporains Villa Delaporte Après la pluie Pierre Gangloff / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 52p 2011 français 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Jacques Barry Angel For Ever / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français 1 art contemporains Yusur-Puentes Programmation culturelle de la Emilia Hernández Pezzi, Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya, Ainhoa Díez de Pablo, espagnol - Paysage et architecture au Maroc et en Présidence espagnole de l’Union Madrid 62p 2010 x 1 El Montacir Bensaïd, Iman Benkirane. français Espagne européenne Chourouk Hriech, Fouad Bellamine, Azzedine Baddou, Hassan Darsi, Ymane Fakhir, Faisal Samra, Fatiha Zemmouri, Mohamed Arejdal, Mohamed El Baz, Philippe Délis, Saad Tazi, Younes Baba Ali, Amande In, Between Walls Abdelmalek Alaoui, Yasmina Naji Yasmina Naji Rabat Integral Editions 44p 2012 français x 1 Anna Raimondo, Mohammed Fettaka, Ymane Fakhir, Mustapha Akrim, Hassan Ajjaj, Hassan Slaoui, Mohamed Laouli, Mounat Charrat, Tarik Oualalou, Fadila El Gadi Mohamed Abdel Benyaich, Hassan Darsi, Mounir Fatmi, Younes Regards Nomades Anne Dary Frédéric Bouglé Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole - France Ville de Dole 42p 1999 français x 1 Rahmoun, Batoul -

Was Undoubtedly the Most Famous Painter of 20Th Century Morocco

Chaïbia Tallal Chaïbia Tallal (1929, 2004) was undoubtedly the most famous painter of 20th century Morocco. She was considered one of the greatest painters in the world, on the same level as Miro, Picasso and Modigliani to name a few. She is the only Moroccan painter whose paintings are quoted on the stock market. Chaïbia Tallal was born in 1929, in the little town of Chtuka, near el-Jadida to a peasant family in the heart of rural Morocco, at a time when education was still the privilege of high-class children. Illiterate, nothing indicated that Chaïbia would one day be an internationally renowned artist whose works would grace collections throughout the world. As a child, she was responsible for looking after the chickens and their chicks. Whenever she lost a chick, she hid in the haystacks for fear of her mother’s anger. This period marked the blossoming of Chaïbia’s imagination. She made flower crowns with which she covered her head and body. When she was at the sea, she made sand houses that had doors and windows, even though she had never seen a house before; she lived with her family members in a tent. During numerous interviews throughout her career, she explained that she painted «all that»: the vastness of the fields, the freshness of the rain, the smell of wet hay, and above all her incommensurable love for the sea, the earth, the rivers, the trees, the flowers, particularly daisies and poppies. Due to this love, her fellow villagers nicknamed her mahbula, the holy fool. -

Art Abstrait & Contemporain Drouot-Richelieu, Salle

artaBstrait&conteMporain Drouot-Richelieu, salle 5-6 Vendredi 9 juin 2017 Lot 126 Vendredi 9 juin 2017 à 14 heures Vente aux enchères publiques Drouot-Richelieu, salle 5-6 9, rue Drouot 75009 Paris ART ABSTRAIT & Responsable de la vente : Xavier DOMINIQUE [email protected] Tél. : 01 78 91 10 12 CONTEMPORAIN Expositions publiques à l’Hôtel Drouot - Salle 5-6 Jeudi 8 juin de 11 h à 21 h Vendredi 9 juin de 11 h à 12 h Téléphone pendant l’exposition : 01 48 00 20 05 Catalogue visible sur www.ader-paris.fr Enchérissez en direct sur www.drouotlive.com En 1re de couverture, est reproduit le lot 63 Lot 126 2 Collection Roger et Bella BELBÉOCH Roger et Bella Belbéoch, tous deux physiciens, s’installent sur l’Ile Saint-Louis au début des années 50. Ils découvrent à cette époque l’effervescence d’une vie parisienne empreinte de culture. Ils se passionnent pour le théâtre, la musique, la littérature. C’est aussi une époque où l’Île Saint-Louis héberge de nombreux artistes connus ou moins connus et beaucoup d’entre eux se retrouvaient tout naturellement à la grande tablée familiale le dimanche pour refaire le monde. Parmi ceux qui devinrent des amis proches on trouvait Gabriel Paris, Édouard Pignon, Pierre Matthey, Louis Bancel et Balthazar et Mercedes Lobo. Ceux-ci se retrouvent même en vacances chez les Bancel à Saint-Julien-Molin-Molette. De ces amitiés résultent les discussions sur la CNT, sur Pablo Picasso avec Mercedes Lobo, sur le fi lm d’Alain Resnais « La guerre est fi nie » avec « Baltha » (comme se plaisaient à l’appeler ses amis), les visites de l’atelier de Balthasar, le portrait de Bella réalisé en 1965, les petits dessins de Baltha qui illustraient chaque année la traditionnelle carte de vœux écrite par Mercedes. -

Vente Décembre 2014

Ventes aux enchères Samedi 27 Décembre 2014 à 16 h 00 SOFITEL - MARRAKECH Art Moderne et Contemporain Peinture Marocaine - Peinture Orientaliste Président Fondateur Chokri Bentaouit Commissaire Priseur Maître Alexandre Millon - Maison Millon et associés - Paris Relations Publiques Hajar Hamanou [email protected] Expositions publiques Jeudi 25 - De 10 h à 20 h Vendredi 26 - De 10 h à 20 h Samedi 27 - De 10 h à 14 h 6, Rue Khalil Metrane - 90000 -Tanger Tel / Fax : +212 539 37 57 07 +212 661 19 73 31 [email protected] www.mazadart.com Editeur : Mazad et Art Conception graphique et crédit photos : Mazad et Art Impression : xxxx HOMMAGE À FARID BELKAHIA Le Maroc contemporain s’expose à l’heure actuelle avec faste et ampleur à Paris à l’Institut du monde arabe et au musée du Louvre soutenu par sa majesté le Roi, dans le cadre d’alliances chaleureuses entre différentes Institutions des deux pays. Un très large éventail de la création contemporaine y est présenté dans un programme qui propose une variété de rendez-vous dans les couleurs et les sonorités que nous connaissons bien. Les artistes marocains sont invités de plus en plus fréquemment hors des frontières du royaume, déplacements leur apportant prospérité et une assise qui gagne en stabilité. Autant dire que l’art permet le dialogue et la compréhension devait préciser Jack Lang, le Président de l’IMA. La culture contribue aussi au développement économique et à l’intégration sociale. Le bouillonnement artistique marocain a donc la capacité de séduire un public de plus en plus large sur le globe. -

Epreuve De Culture Générale Durée : 1 Heure

Concours d’accès en première année Programme Grande Ecole Session de Juillet 2019 (24/07/2019) Epreuve de Culture Générale Durée : 1 heure Des questions à choix multiples (QCM) vous sont proposées. Elles sont rangées par catégorie : - Culture et géographie - Politique, société et actualités - Arts et littérature - Sport - Sciences et techniques Chacune de ces catégories comprend 8 questions à choix multiples (0.5 points chacune) et 2 questions ouvertes (1 point chacune). Vous devez répondre à toutes les questions de chaque catégorie. Consignes : - Pour les questions à choix multiples (QCM), entourez une et une seule réponse. - Pour les questions ouvertes, rédigez votre réponse brièvement. - 1 - I. Culture et géographie 1- Comment appelle-t-on la demeure présidentielle aux Etats Unis ? a. Le Panthéon b. La Maison Blanche 6- La Fantasia est un spectacle traditionnel marocain pratiqué à c. L’Elysée l’aide de : d. Le Colisée a. Chevaux b. Singes 2- Comment s’appelle l’organisme international qui fédère les c. Serpents pays africains ? d. Motos a. UNICEF b. OMC 7- Dans quelle ville du Maroc sont développés les projets c. UA énergétiques NOOR ? d. UMA a. El Jadida 3- Où se trouvent « Les jardins Majorelle » : b. Ouarzazate a. Fès c. Khouribga b. Agadir d. Taza c. Marrakech d. Casablanca 8- Quelle est la monnaie de la Tunisie ? e. Dinar 4- Quels sont les deux pays frontaliers de l’Espagne ? f. Lire a. France et Italie g. Dirhams b. Portugal et Suisse h. Euro c. France et Belgique d. France et Portugal Questions ouvertes 7- Lequel de ces pays est accessible aux marocains sans VISA ? : 1- Comment s’appelle la montagne la plus haute du Maroc ? a. -

Smart Museums: Enjoying Culture Virtually Case of Virtual Museum of the National Museums Foundation

Smart museums: enjoying culture virtually Case of Virtual Museum of the National Museums Foundation. Rabat - Morocco Ikrame SELKANI, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain [email protected] Abstract Before, the city was a space dedicated to offering a range of services to all the inhabitants who lived there, such as public transportation, education, housing.... However, things have undergone a certain change with the introduction of the Internet and ICTs. To this end, we have today began to hear about -Smart City-this new emerging concept leaves no major metropolis untouched. The digital and modern age has affected almost every sector, even those who imagined they were frozen in time, thanks to the cities have experienced the technologies were throughout the early 21st century. Here, we cite for example: the world of banks, telecommunications, service companies ... even the public sector such as: education, culture, administration. Future museums may also contribute to human culture in a society witnessing rapid changes via smart museum technology that encourages constructive participation with the public. Digital technologies did not emerge overnight in museums and started by replacing conventional analog broadcasting media without altering the experience of visitors. What is really new is the appearance, which includes screens near the works giving more information. The term "virtual museum" has been defined as follows: "... a collection of digitized objects logically articulated and composed of various supports which, due to its connectivity and character multi-access, allow you to transcend traditional modes of communication and interaction with the visitor... " [2]. Our study case will also reach the Virtual Museum of the National Museums Foundation Rabat Morocco.