1 Land Reform and Peasant Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Presentation Slides

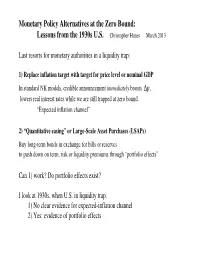

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Strikes and Rural Unrest During the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1936): a Geographic Approach

sustainability Article Strikes and Rural Unrest during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1936): A Geographic Approach Javier Puche 1,* and Carmen González Martínez 2 1 Faculty of Social and Human Sciences, University of Zaragoza, Ciudad Escolar s/n, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Faculty of Letters, University of Murcia, Campus de la Merced, 30071 Murcia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-337 Received: 27 October 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018; Published: 21 December 2018 Abstract: This article analyses the evolution and geographic distribution of the rural unrest that prevailed during the years of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1936), a period characterised by political instability and social conflict. The number of provincial strikes recorded in the forestry and agricultural industries and complied by the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare constitute the primary source of the study. Based on this information, maps of the regional and provincial distribution of the agricultural unrest have been created for the republican period. The results reveal that, contrary to the traditional belief which confines the rural unrest of this period to the geographic areas of the latifundios (large estates), Spanish agriculture, in all its diversity, was hit by collective disputes. Although the areas of the latifundios were most affected by the agricultural reform of 1932, the data show that the extension of the unrest in the Spanish countryside was also the result of the refusal of the landowners to accept and apply the new republican collective bargaining agreement. The number of strikes increased during the period 1931–1933, fell between 1934 and 1935, and increased again during the months of the Popular Front (February to July 1936). -

The Labour Party and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939

1 Britain and the Basque Campaign of 1937: The Government, the Royal Navy, the Labour Party and the Press. To a large extent, the reaction of foreign powers dictated both the course and the outcome of the Civil War. The policies of four of the five major protagonists, Britain, France, Germany and Italy were substantially influenced by hostility to the fifth, the Soviet Union. Suspicion of the Soviet Union had been a major determinant of the international diplomacy of the Western powers since the revolution of October 1917. The Spanish conflict was the most recent battle in a European civil war. The early tolerance shown to both Hitler and Mussolini in the international arena was a tacit sign of approval of their policies towards the left in general and towards communism in particular. During the Spanish Civil War, it became apparent that this British and French complaisance regarding Italian and German social policies was accompanied by myopia regarding Fascist and Nazi determination to alter the international balance of power. Yet even when such ambitions could no longer be ignored, the residual sympathy for fascism of British policy-makers ensured that their first response would be simply to try to divert such ambitions in an anti-communist, and therefore Eastwards, direction.1 Within that broad aim, the Conservative government adopted a general policy of appeasement with the primary objective of reaching a rapprochement with Fascist Italy to divert Mussolini from aligning with a potentially hostile Nazi Germany and Japan. Given the scale of British imperial commitments, both financial and military, there would be no possibility of confronting all three at the same time. -

The Olimpiada Popular: Barcelona 1936, Sport and Politics in an Age of War, Dictatorship and Revolution

Article The Olimpiada Popular: Barcelona 1936, Sport and Politics in an Age of War, Dictatorship and Revolution Physick, Ray Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/19183/ Physick, Ray (2016) The Olimpiada Popular: Barcelona 1936, Sport and Politics in an Age of War, Dictatorship and Revolution. Sport in History, 37 (1). pp. 51-75. ISSN 1746-0263 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17460263.2016.1246380 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk The Olimpiada Popular: Barcelona 1936 Sport and Politics in an age of War, Dictatorship and Revolution In an attempt to undermine the IOC Games of 1936, organisations linked to the international worker sport movement responded to an invitation from the Comité Organizador de la Olimpiada Popular (COOP) to take part in an alternative Olympics, the Olimpiada Popular, in Barcelona in July 1936. It is estimated that some 10,000 athletes and 25,000 visitors were in Barcelona to celebrate the Olimpiada. -

Soviet Intervention in the Spanish Civil War: Review Article

Ronald Radosh Sevostianov, Mary R. Habeck, eds. Grigory. Spain Betrayed: The Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001. xxx + 537 pp. $35.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-300-08981-3. Reviewed by Robert Whealey Published on H-Diplo (March, 2002) Soviet Intervention in the Spanish Civil War: the eighty-one published documents were ad‐ Review Article dressed to him. Stalin was sent at least ten. Stalin, [The Spanish language uses diacritical marks. the real head of the Soviet Union, made one direct US-ASCII will not display them. Some words, order to the Spanish government, on the conser‐ therefore, are written incompletely in this re‐ vative side. After the bombing of the pocket bat‐ view] tleship Deutschland on 29 May 1937 (which en‐ raged Hitler), Stalin said that the Spanish Republi‐ This collection is actually two books wrapped can air force should not bomb German or Italian in a single cover: a book of Soviet documents pre‐ vessels. (Doc 55.) sumably chosen in Moscow by Grigory Sevos‐ tianov and mostly translated by Mary Habeck. From reading Radosh's inadequate table of Then the Soviet intervention in Spain is narrated contents, it is not easy to discover casually a co‐ and interpreted by the well-known American his‐ herent picture of what the Soviets knew and were torian Ronald Radosh. Spain Betrayed is a recent saying during the civil war. Archival information addition to the continuing Yale series, "Annals of tends to get buried in the footnotes and essays Communism," edited with the cooperation of Rus‐ scattered throughout the book, and there is no sian scholars in Moscow. -

The Composition of the Court

THE COMPOSITION OF THE COURT I. THE PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE First Period (1 January 1922-31 December 1930) B. Altamira y Crevea (Spain) D. Anzilotti (President, 1928-1930) (Italy) R. Barbosa (d. 1 March 1923) (Brazil) A.S. de Bustamante y Sirven (Cuba) Viscount Finlay (d. 9 March 1929) (United Kingdom) H. Fromageot (from 19 September 1929) (France) H.M. Huber (President 1925-1927, Vice-President 1928-1931) (Switzer- land) C.E. Hughes (from 8 September 1928, resigned 15 February 1930) (United States of America) C.J.B. Hurst (from 19 September 1929) (United Kingdom) F.B. Kellog (from 25 September 1930) (United States of America) D.C.J. Loder (President 1922-1924) (the Netherlands) J.B. Moore (resigned 11 April 1926) (United States of America) D.G.G. Nyholm (Denmark) Y. Oda (Japan) E.d.S. Pessôa (from 10 September 1923) (Brazil) C.A. Weiss (Vice-President 1922-1928, d. 31 August 1928) (France) Deputy-Judges F.V.N. Beichmann (Norway) D. Negulesco (Romania) Wang, Ch’ung-hui (China) M. Yovanovich (Yugoslavia) Second Period (1 January 1931-18 April 1946) M. Adatci (President 1931-1933, d. 28 December 1934) (Japan) R. Altamira y Crevea (Spain) D. Anzilotti (Italy) A.S. de Bustamante y Sirven (Cuba) Cheng Tien-Hsi (from 8 October 1936) (China) 1706 The Composition of the Court R.W. Erich (from 26 September 1938) (Finland) W.J.M. van Eysinga (the Netherlands) H. Fromageot (France) J.G. Guerrero (Vice-President 1931-1936, President 1936-1946) (El Salvador) Åke Hammarskjöld (from 8 October 1936, d. 7 July 1937) (Sweden) M.O. -

The Spanish Civil War (1936–39)

12 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 1: THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936–39) ‘A civil war is not a war but a sickness,’ wrote Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. ‘The enemy is within. One fights almost against oneself.’ Yet Spain’s tragedy in 1936 was even greater. It had become enmeshed in the international civil war, which started in earnest with the Bolshevik revolution. From Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939 , 2006 The Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936 after more than a century of social, economic and political division. Half a million people died in this conflict between 1936 and 1939. As you read through this chapter, consider the following essay questions: Ģ Why did a civil war break out in Spain in 1936? Ģ How significant was the impact of foreign involvement on the outcome of the Spanish Civil War? General Francisco Franco, the Ģ What were the key effects of the Spanish Civil War? leader who took Nationalist forces to victory in the Spanish Civil War. Timeline of events – 1820–1931 1820 The Spanish Army, supported by liberals, overthrows the absolute monarchy and makes Spain a constitutional monarchy in a modernizing revolution 1821 Absolute monarchy is restored to Spain by French forces in an attempt to reinstate the old order 1833 In an attempt to prevent a female succession following the death of King Ferdinand, there is a revolt by ‘Carlists’. The army intervenes to defeat the Carlists, who nevertheless remain a strong conservative force in Spanish politics (see Interesting Facts box) 1833–69 The army’s influence in national politics increases during the ‘rule of the Queens’ 1869–70 Anarchist revolts take place against the state 1870–71 The monarchy is overthrown and the First Republic is established 1871 The army restores a constitutional monarchy 1875–1918 During this period the constitutional monarchy allows for democratic elections. -

Basic Information and Reading Recommendations Regarding the History and the Legacies of the Spanish Civil War

Memory Lab 8th annual study trip and workshop, 17 -23 September 2017: Madrid, Belchite, Barcelona, La Jonquera, Rivesaltes Basic information and reading recommendations regarding the history and the legacies of the Spanish Civil War 1. The history of Spain in the 20th century, with a special emphasis on the Spanish Civil War 1936- 1939 1.1. Some basic information 1.2. Reading recommendations 2. Legacies and memories of the Spanish Civil War, from 1939 until today 2.1. Some basic information 2.2. Reading recommendations 3. Glossary: Important terms and names regarding the Spanish Civil War and its memories 4. Infos and links about the sites we will visit during our program 1. The history of Spain in the 20th Century, with a special emphasis on the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 1. 1. Some basic information 1.1.1. The Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939) → 14. April 1931: After centuries of monarchic reign in Spain (with a short Republican intermezzo in 1873/4), the Second Spanish Republic is proclaimed and King Alfonso XIII flees the country, following the landslide victory of anti-monarchist forces at the municipal elections two days earlier. → Some characteristics for the following years: many important reforms (for example land reform, right to vote for women, autonomy for Catalonia and other regions) ; political tensions within the republican governing parties, between more leftist and more conservative tendencies, accompanied by strikes and labour conflicts ; at the general elections in February 1936 victory of the Popular Front regrouping different left-wing political organisations, including socialists and communists. Non- acceptance of the new Republican regime by monarchist and nationalist forces. -

1935 Sanctions Against Italy: Would Coal and Crude Oil Have Made a Difference?

1935 SANCTIONS AGAINST ITALY: WOULD COAL AND CRUDE OIL HAVE MADE 1 A DIFFERENCE? CRISTIANO ANDREA RISTUCCIA LINACRE COLLEGE OXFORD OX1 3JA GREAT BRITAIN Telephone 44 1865 721981 [email protected] 1 Thanks to (in alphabetical order): Dr. Leonardo Becchetti, Sergio Cardarelli (and staff of the ASBI), Criana Connal, John Fawcett, Prof. Charles Feinstein, Dr. James Foreman-Peck, Paola Geretto (and staff of the ISTAT library and archive), Gwyneira Isaac, Clare Pettitt, Prof. Maria Teresa Salvemini, Prof. Giuseppe Tattara, Leigh Shaw-Taylor, Prof. Gianni Toniolo, Dr. Marco Trombetta, and two anonymous referees who made useful comments on a previous version of this paper. The responsibility for the contents of the article is, of course, mine alone. ABSTRACT This article assesses the hypothesis that in 1935 - 1936 the implementation of sanctions on the export of coal and oil products to Italy by the League of Nations would have forced Italy to abandon her imperialistic war against Ethiopia. In particular, the article focuses on the claim that Britain and France, the League’s leaders, could have halted the Italian invasion of Ethiopia by means of coal and oil sanctions, and without the help of the United States, or recourse to stronger means such as a military blockade. An analysis of the data on coal consumption in the industrial census of 1937 - 1938 shows that the Italian industry would have survived a League embargo on coal, provided that Germany continued her supply to Italy. The counterfactual proves that the effect of an oil embargo was entirely dependent on the attitude of the United States towards the League’s action. -

Scrapbook Inventory

E COLLECTION, H. L. MENCKEN COLLECTION, ENOCH PRATT FREE LIBRARY Scrapbooks of Clipping Service Start and End Dates for Each Volume Volume 1 [sealed, must be consulted on microfilm] Volume 2 [sealed, must be consulted on microfilm] Volume 3 August 1919-November 1920 Volume 4 December 1920-November 1921 Volume 5 December 1921-June-1922 Volume 6 May 1922-January 1923 Volume 7 January 1923-August 1923 Volume 8 August 1923-February 1924 Volume 9 March 1924-November 1924 Volume 10 November 1924-April 1925 Volume 11 April 1925-September 1925 Volume 12 September 1925-December 1925 Volume 13 December 1925-February 1926 Volume 14 February 1926-September 1926 Volume 15 1926 various dates Volume 16 July 1926-October 1926 Volume 17 October 1926-December 1926 Volume 18 December 1926-February 1927 Volume 19 February 1927-March 1927 Volume 20 April 1927-June 1927 Volume 21 June 1927-August 1927 Volume 22 September 1927-October 1927 Volume 23 October 1927-November 1927 Volume 24 November 1927-February 1928 Volume 25 February 1928-April 1928 Volume 26 May 1928-July 1928 Volume 27 July 1928-December 1928 Volume 28 January 1929-April 1929 Volume 29 May 1929-November 1929 Volume 30 November 1929-February 1930 Volume 31 March 1930-April 1930 Volume 32 May 1930-August 1930 Volume 33 August 1930-August 1930. Volume 34 August 1930-August 1930 Volume 35 August 1930-August 1930 Volume 36 August 1930-August 1930 Volume 37 August 1930-September 1930 Volume 38 August 1930-September 1930 Volume 39 August 1930-September 1930 Volume 40 September 1930-October 1930 Volume -

League of Nations

LEAGUE OF NATIONS (Communicated to the C.317 .M.I9 8 .I9 3 6 . Members of the League.) Geneva, August 1st, 193&. NUMERICAL LIST OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO THE MEMBERS OF THE LEAGUE. No» 7 (July 1936) Official number SUBJECT C.4 2 9 (b).M.2 2 0 (b).I9 3 5 .XI * Estimated world requirements of dangerous drugs in 1 9 - 2nd Supplement to the statement of the Opium Supervisory Body. C.4 2 9 (c).M.220(b)*1935„XI * Estimated world requirements of dangerous drugs in l^b. - 3rd Supplement to the state ment of the Opium Supervisory Body. C.24(1).M.l6 (l).1 9 3 6 , Erratum I Committees and Commissions of the League. - Erratum, to the .list of Members. C.9 4 .M.3 7 .1 9 3 6 .IV ** Assistance to indigent foreigners and execution of maintenance obligations abroad. - Report and second draft multilateral convention by the Committee of Experts (2nd Session, January- February 1 9 3 6 ). C.128.M.6 7 .1936.VIII, Addendum Uniform system of maritime buoyage. - Observa tions of Portugal on the report of July 1933 of Preparatory Committee. C.204.M. 127 .1936*IV, *** and Erratum Traffic in Women and Children Committee (l5th Session , April lQ^b)'Child Welfare Committee 12th Session, April-May 193b' Reports and Erratum to reports. ^ Confidential ** Redistributed with C„L <,118.1936. IV *** One copy redistributed with C.L.107•193^*IV - 2 - C.214.1936.IV.* Assistance to indigent foreigners and exe - • • cution of maintenance obligations abroad.- Report by the Chilian Representative.