Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moving Freight 2019 “Towards a 20 Year State Infrastructure Strategy”

South Australia’s Freight Transport Infrastructure Moving Freight 2019 “Towards a 20 Year State Infrastructure Strategy” July 2019 South Australian Freight Council Inc Level 1, 296 St Vincent Street Port Adelaide SA 5015 Tel.: (08) 8447 0664 Email: [email protected] www.safreightcouncil.com.au The South Australian Freight Council Inc is the State’s peak multi-modal freight and logistics industry group that advises all levels of government on industry related issues. SAFC represents road, rail, sea and air freight modes and operations, Freight service users (customers) and assists the industry on issues relating to freight and logistics across all modes. Disclaimer: While the South Australian Freight Council has used its best endeavours to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this report, much of the information provided has been sourced from third parties. Accordingly, SAFC accepts no liability resulting from the accuracy, interpretation, analysis or use of information provided in this report. In particular, infrastructure projects and proposals are regularly adjusted and amended, and those contained in this document, whilst accurate when sourced, may have changed and/or been amended. Contents Chairman’s Message Page 02 Executive Summary Page 03 Introduction Page 05 Core Infrastructure Principles / Policy Issues Page 08 Core Infrastructure Criteria Page 09 Overarching Strategy Needs and Integration Page 10 Protecting Freight Capability – A Public Asset Page 12 SAFC Priority Projects Page 14 Urgent Projects Page -

Towards More Sustainable Cities: Building a Public Transport Culture

Towards More Sustainable Cities: Building a Public Transport Culture Submission by the Bus Industry Confederation to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment and Heritage’s Inquiry into Sustainable Cities 2025. Canberra, October, 2003. Table of Contents Executive Summary Key Findings Some Particular Conclusions 1. Scope ...................................................................................................................... 2. The Sustainability of Australia’s City Transport Systems ........................................ 2.1 Sustainability Criteria........................................................................................... 2.2 Externalities ......................................................................................................... 2.3 Economic Sustainability....................................................................................... 2.3.1 Congestion Costs ........................................................................................... 2.3.2 Dynamic Urban Economies............................................................................ 2.4 Improving Access................................................................................................. 2.4.1 Melbourne ..................................................................................................... 2.4.2 Sydney........................................................................................................... 2.4.3 Hobart........................................................................................................... -

The Relationship Between Transport and Disadvantage in Australia Kate Rosier & Myfanwy Mcdonald

AUGUST 2011 resource sheet COMMUNITIES AND FAMILIES CLEARINGHOUSE AUSTRALIA The relationship between transport and disadvantage in Australia Kate Rosier & Myfanwy McDonald This Resource Sheet is designed to provide practitioners and policy-makers who plan and/or deliver services to children and families, especially within disadvantaged communities, with an understanding of how transport and disadvantage intersect and why some groups are especially vulnerable to transport disadvantage. Key messages Ongoing difficulties associated with access to transport are commonly referred to as “transport disadvantage”. As Australia has comparatively high levels of car ownership, difficulties associated with maintaining private transport (e.g., financial stress related to initial cost of purchase, as well ongoing costs such as petrol, insurance, car purchase and maintenance) could also be included in the overall definition of transport disadvantage. The proportion of Australians who feel they cannot or often cannot get to places they need to visit is fairly small (4%). However, Australians in the bottom income quintile are much more likely to experience transport difficulties than those in the top income quintile (9.9% and 1.3% respectively) (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2006). Transport disadvantage is experienced by specific sub-groups in the population, for example, families with young children, people with a disability and Indigenous Australians. Transport disadvantage is also common in specific geographical locations such as outer-urban (or “fringe”) areas, rural and remote Australia. In outer-urban areas transport disadvantage is the result of a range of intersecting factors including poor public transport infrastructure, a higher proportion of low-income households and the need to travel further distances in order to get to places of employment, services and activities. -

Distribution 2020: Situational Analysis

pwc.com.au Distribution 2020: Situational Analysis Tourism Australia Distribution in Australia’s international markets: Situational Analysis March 2013 Final Report Key Findings There is no one agreed definition of ‘tourism distribution’ across both industry participants and government bodies. Some viewed the term ‘distribution’ to be the interaction of customers with travel agents and other traditional intermediary, or third party channels. In this context, communicating directly with customer was thought of as ‘marketing’ activity. The other view was that distribution encompasses any action or channel that connects customers with tourist products, be it through direct communication or through third parties. While the general idea of linking a customer through to a travel and tourism product is a consistent theme across both these views, we have adopted the broader all-encompassing definition, as this better aligns with changes in how consumers are purchasing travel products, and how industry has responded to these changes. In this study we are seeking to: understand the relevance of different tourism distribution approaches now and in the future across Australia’s key holiday markets. review the current structure and activities of Tourism Australia and state tourism organisations (STOs). While specific data across sources is fragmented and hence clouds the view of the future, the key findings of our initial review, consumer survey and stakeholder interviews are: There is a clear trend towards a greater role of online sources for identifying Australia as a holiday destination, and then planning, booking and subsequently sharing holiday experiences. Indeed, the identification of Australia as a destination, and the planning of a holiday, increasingly is undertaken online. -

Exploring Everyday Cultures of Transport in Chinese Migrant Households in Sydney

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Social Sciences - Honours Theses University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2014 Exploring Everyday Cultures of Transport in Chinese Migrant Households in Sydney Sophie-May Kerr University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/thss University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Kerr, Sophie-May, Exploring Everyday Cultures of Transport in Chinese Migrant Households in Sydney, Department of Geography and Sustainable Communities, University of Wollongong, 2014. -

Australian Streamliners Locomotive Fleetlist.Indd

Australian Streamliners Locomotive fleetlist Mount Newman Mining F7A – EMD model F7A built La Grange, Illinois, USA 1,500hp Bo-Bo single-ended diesel-electric LOCO # BUILDER'S # BUILT CURRENT OWNER LIVERY STATUS NOTES 5450 8970 1950 Pilbara Railway Historical Society, Six MNM orange & red Preserved on display Ex-Western Pacific Mile, WA (1,435mm) (USA) 917A. Purchased by Mount Newman Mining in 1968. 5451 10805 1950 Don Rhodes Mining and Transport MNM orange & red Preserved on display Ex-Western Pacific Museum, WA (1,435mm) (USA) 923A. Purchased by Mount Newman Mining in 1968. South Australian Railways 900 Class – English Electric built SAR Inslington, South Australia 1,500hp A1A-A1A single-ended diesel-electric LOCO # BUILDER'S # BUILT CURRENT OWNER LIVERY STATUS NOTES 900 1848 1951 National Railway Museum, Port SAR red & silver Preserved on display Named Lady Adelaide, South Australia (1,600mm) Norrie. 907 1855 1953 Australian Locomotive and Railway SAR silver & red Preserved stored - Carriage Company, Tailem Bend, South (1,600mm) Australia 909 1857 1953 Australian Locomotive and Railway undercoat Undergoing - Carriage Company, Tailem Bend, South restoration Australia (1,435mm) Commonwealth Railways GM1 Class – Clyde/EMD model ML-1 built Granville, NSW, Australia 1,500hp A1A-A1A single-ended diesel-electric LOCO # BUILDER'S # BUILT CURRENT OWNER LIVERY STATUS NOTES GM1 ML1-1 1951 Rail Heritage Western Australia CR maroon & silver Stored at Parkes, Named Robert NSW (1,435mm) Gordon Menzies. GM2 ML1-2 1951 National Railway Museum, Port CR maroon & silver Preserved on display - Adelaide, South Australia (1,435mm) GM3 ML1-3 1951 Southern Shorthaul Railroad CR maroon & silver Stored at Lithgow, Named Ray E NSW (1,435mm) Purves. -

Full Year Report 12 Months to 30 June 2012

Full Year Report 12 months to 30 June 2012 Financial Performance $m FY121 FY111 Change (%) Total revenue2 8,524.6 6,960.9 22.5 EBITDA 593.7 502.7 18.1 EBIT 346.5 292.2 18.6 Net interest expense (69.0) (64.3) 7.3 Tax expense (82.1) (61.5) 33.5 Net profit after tax 195.3 166.4 17.4 ROFE3 17.7% 15.8% 1.9 1 Numbers are “underlying”, i.e. excluding Individually Significant Items 2 Total revenue is a non-statutory disclosure and includes revenue, other income and notional revenue from joint ventures and other alliances not proportionately consolidated. 3 ROFE = EBIT divided by average funds employed (AFE) (AFE = Average Opening and Closing Net Debt = Equity) Total Revenue2 ($m) EBIT1 ($m) 9000 360 8000 350 7000 340 330 6000 320 5000 310 4000 300 3000 290 2000 280 1000 270 0 260 FY10 FY11 FY12 FY10 FY11 FY12 EBITDA1 ($m) Work-in-hand ($b) 700 25 600 20 500 15 400 300 10 200 5 100 0 0 FY10 FY11 FY12 FY10 FY11 FY12 2 THE YEAR TO 30 JUNE 2012 Downer made significant progress during the 2012 financial year and the strength of the business is clear in the full year result. All Downer businesses continued to win new work and work-in-hand remains high at $20 billion. Downer’s portfolio structure is now well defined with the establishment of Downer Infrastructure in May 2012 (bringing together the Group’s infrastructure businesses in Australia and New Zealand) and the completion of the sale of CPG Asia for $147 million in April 2012. -

Rail Reform Strategies: the Australian Experience

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES RAIL REFORM STRATEGIES: THE AUSTRALIAN EXPERIENCE Helen Owens Working Paper 9592 http://www.nber.org/papers/w9592 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2003 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. ©2003 by Helen Owens. All rights reserved. Short sections of text not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit including ©notice, is given to the source. Rail Reform Strategies: The Australian Experience Helen Owens NBER Working Paper No. 9592 March 2003 JEL No. D4, L9 ABSTRACT Widely different approaches to rail reform are evident across countries and within Australia. Reforms have involved structural separation (both vertical and horizontal) and varying degrees of private sector involvement. Evidence from Australian experience suggests that no one size fits all. The characteristics of rail networks - namely the degree of market power, the strength of intermodel competition, competition in downstream markets and traffic density would all influence the approach adopted. These differ for urban passenger, regional freight (general and bulk) and long distance networks. The potential implications for future rail reform are outlined. Helen Owens Australian Productivity Commission Melbourne Office Level 28, 35 Collins Street Melbourne, VIC 3000 Australia [email protected] 3 Helen Owens I Introduction1 Railways began operating in Australia in the 1850s and, in many ways, they transformed transport in the country. They became vital links between Australia’s cities and ports and the rural hinterland, facilitated export expansion and were used by governments to pursue social and political objectives (PC 1999). -

Roadmasters House Museum End of Year Function

November 2017 National Trust eNews The National Trust of Australia (NT) is a community based, not for profit heritage charity dedicated to promoting and conserving the heritage of the Northern Territory. Inside November Edition Page 2 Our volunteers receive some much-deserved recognition! BRANCH NEWS Page 3 Roadmaster’s House Museum’s end of year function Page 4 Stahl Garden clean up Page 5 Hartley Street School Research Page 6 Upcoming Events Myilly Point Heritage Precinct Audit House, 2 Burnett Place, Larrakeyah NT 0820 GPO Box 3520, Darwin NT 0801 Ph: 08 8981 2848 Email: [email protected] www.nationaltrust.org.au/nt Our Superb Volunteers receive recognition Message 1: Tom, at Burnett House, Volunteer at Larrakeyah Branch of the Trust. We visited on Saturday 23 Sept 2017. We arrived at noon and were offered a tour by Tom. We were the only ones there so we had a very personal tour and conversations. What a wealth of information Tom is about the House and Darwin and NT and Australia. He knew every detail and corner of the house because he lived there as a young man! Even a minor improvement he made to the bedroom still exists! He answered every question we had about the structure, the customs of the times and why the house survived Cyclone Tracy. Nothing was too much for Tom address. The House was scheduled to close at 1 pm but we were still there at 1:30. Tom did not rush us out the door. We thoroughly enjoyed the visit with Tom at Burnett House. -

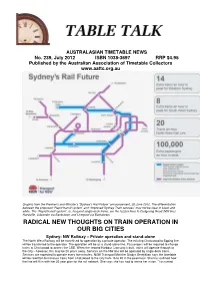

Radical New Thoughts on Train Operation in Our Big

AUSTRALASIAN TIMETABLE NEWS No. 239, July 2012 ISBN 1038-3697 RRP $4.95 Published by the Australian Association of Timetable Collectors www.aattc.org.au Graphic from the Premier’s and Minister’s “Sydney’s Rail Future” announcement, 20 June 2012. The differentiation between the proposed “Rapid transit system” and “Improved Sydney Train services” may not be clear in black and white. The “Rapid transit system”, ie, frequent single-deck trains, are the fuzzier lines to Cudgeong Road (NW line) Hurstville, Lidcombe via Bankstown and Liverpool via Bankstown. RADICAL NEW THOUGHTS ON TRAIN OPERATION IN OUR BIG CITIES Sydney: NW Railway – Private operation and stand-alone The North West Railway will be franchised for operation by a private operator. The existing Chatswood to Epping line will be transferred to the operator. The operation will be as a stand-alone line. Passengers will be required to change trains at Chatswood to access the CBD. When the second Harbour Crossing is built, trains will operate through to the City – however, this may be 20 years away. Services on the NW line will be operated by single deck trains. Services are expected to operate every five minutes. NSW Transport Minister Gladys Berejiklian says the timetable will be rewritten to increase trains from Chatswood to the City from 16 to 20 in the peak hour. She has outlined how the line will fit in with her 20-year plan for the rail network. She says she has had to revise her vision. "I assumed when I became Transport Minister that double decks were the way to go but expert advice, community input, industry input, demonstrates to me and also looking at what happens around the world, the best way to go for the north-west rail line is single deck," she said. -

4 February 2016 Company Announcements Office ASX

Downer EDI Limited ABN 97 003 872 848 Triniti Business Campus 39 Delhi Road North Ryde NSW 2113 1800 DOWNER www.downergroup.com 4 February 2016 Company Announcements Office ASX Limited Exchange Centre Level 4, 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Sir/Madam Please find attached the following documents: 1. Appendix 4D – results for announcement to the market for the half-year ended 31 December 2015; 2. Condensed Consolidated Half-year Financial Report dated 31 December 2015; 3. Market release dated 4 February 2016; and 4. Investor Presentation. Yours sincerely, Downer EDI Limited Peter Tompkins Company Secretary Page 1 of 1 Results for announcement to the market for the half-year ended 31 December 2015 Appendix 4D 31 Dec 2015 31 Dec 2014 change $'m $'m % Revenue from ordinary activities 3,262.0 3,375.0 Other income 2.6 2.8 Total revenue and other income from ordinary activities 3,264.6 3,377.8 (3.4%) Total revenue including joint ventures and other income 3,543.4 3,586.0 (1.2%) Earnings before interest and tax 113.2 141.7 (20.1%) Profit from ordinary activities after tax attributable to members of the parent entity 72.1 94.7 (23.9%) 31 Dec 2015 31 Dec 2014 change cents cents % Basic earnings per share 15.8 20.8 (24.0%) Diluted earnings per share 15.1 20.1 (24.9%) Net tangible asset backing per ordinary share 254.2 253.5 0.3% Dividend 31 Dec 2015 31 Dec 2014 Interim Interim Dividend per share (cents) 12.0 12.0 Franked amount per share (cents) 12.0 12.0 Dividend record date 18/02/2016 19/02/2015 Dividend payable date 17/03/2016 19/03/2015 Redeemable Optionally Adjustable Distributing Securities (ROADS) Dividend per ROADS (in Australian cents) 2.40 2.65 New Zealand imputation credit percentage per ROADS 100% 100% ROADS payment date Quarter 1 Quarter 2 Instalment date FY2016 15/09/2015 15/12/2015 Instalment date FY2015 15/09/2014 15/12/2014 Downer EDI's Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) has been suspended. -

Downer Group Business Profile (April 2014)

Shaping the Future of Railway Institute of Railway Technology 21st September 2016 Adams Williams Manufacturing Lead Major Bids Team Rail Relationships creating success Opportunities in Rail Page 2 Trains, Trams, Jobs 2015 – 2025 WHY WE NEED MORE TRAINS AND TRAMS SUPPORTING LOCAL JOBS Victoria’s train and tram building industry supports up to 10,000 jobs. TRANSFORMING THE RAIL NETWORK The Andrews Labor Government is expanding and growing our rail network. MEETING FUTURE NEEDS Our rail capacity needs to grow along with Melbourne’s growing population. AN AGEING TRAIN AND TRAM FLEET Our train and tram fleet is ageing and needs constant refreshing. A BETTER PASSENGER EXPERIENCE New trams and next-generation trains mean a better Reference: Extracts from Trains, Trams Jobs 2015 -2025. Victorian Rolling Stock Strategy. State Government passenger experience. Victoria. © Downer Group Limited All rights reserved Page 3 Strong pipeline of opportunities 300 252 237 237 237 237 236 234 250 220 212 212 208 15 30 48 61 NEW 200 74 87 100 METROPOLITAN 150 100 211 211 216 216 212 202 188 178 TRAINS 163 158 153 50 0 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 Existing fleet in service HCMT Total train requirement 500 442 428 416 450 407 397 385 373 400 360 346 332 5 20 35 75 160 350 307 120 140 300 NEW 250 200 REGIONAL 331 352 361 361 361 361 333 150 309 295 284 284 TRAINS 100 50 0 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 Total existing fleet Total new fleet Total carriage requirement © Downer Group Limited All rights reserved Page 4 HCMT Project © Downer Group Limited All rights reserved Page 5 Relationships creating success About Downer Page 6 Overall Business Profile Market Revenue Work-in-hand People capitalisation (FY 2016) approx.