Message to the Mayor 2020 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Guineas Sweep for Godolphin Cont

MONDAY, 13 MAY 2019 CLEAN SWEEP FOR O=BRIEN FRENCH GUINEAS SWEEP By Tom Frary FOR GODOLPHIN AThere are a lot of horses there@, commented Aidan O=Brien in his typically understated way at Leopardstown on Sunday as he pondered the stable=s tsunami of Epsom Derby hopefuls including the easy G3 Derrinstown Stud Derby Trial S. scorer Broome (Ire) (Australia {GB}). Ballydoyle have now won every recognised Derby trial in Britain and Ireland in 2019 and this talented and progressive colt is responsible for two having rated a very impressive winner of the Apr. 6 G3 Ballysax S. over this course and distance. Uncovering which of the yard=s plethora of contenders for the blue riband will come out on top was an already taxing pursuit, but after another convincing prep performance from Broome it is fitting more into the unsolvable conundrum criteria. Cont. p6 Persian King justifies favouritism in the Poulains | Scoop Dyga By Tom Frary IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Testing conditions at ParisLongchamp on Sunday created by a THE WEEK IN REVIEW deluge of rain meant that equine pyrotechnics were unlikely With litigation likely in the wake of a controversial finish to the despite the formidable presence of Persian King (Ire) (Kingman GI Kentucky Derby, fans should get tied on for a long ride. {GB}). Hot favourite for the G1 The Emirates Poule d=Essai des Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. Poulains, Godolphin and Ballymore Thoroughbred Ltd=s >TDN Rising Star= duly won, but it was more a case of a thankless task being carried out in professional manner as he delivered a first Classic success for his exhilarating sire. -

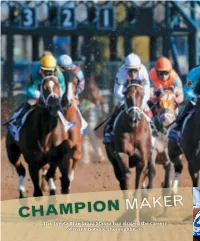

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

A Theological Reading of the Gideon-Abimelech Narrative

YAHWEH vERsus BAALISM A THEOLOGICAL READING OF THE GIDEON-ABIMELECH NARRATIVE WOLFGANG BLUEDORN A thesis submitted to Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts & Humanities April 1999 ABSTRACT This study attemptsto describethe contribution of the Abimelech narrative for the theologyof Judges.It is claimedthat the Gideonnarrative and the Abimelechnarrative need to be viewed as one narrative that focuseson the demonstrationof YHWH'S superiority over Baalism, and that the deliverance from the Midianites in the Gideon narrative, Abimelech's kingship, and the theme of retribution in the Abimelech narrative serve as the tangible matter by which the abstracttheological theme becomesnarratable. The introduction to the Gideon narrative, which focuses on Israel's idolatry in a previously unparalleled way in Judges,anticipates a theological narrative to demonstrate that YHWH is god. YHwH's prophet defines the general theological background and theme for the narrative by accusing Israel of having abandonedYHwH despite his deeds in their history and having worshipped foreign gods instead. YHWH calls Gideon to demolish the idolatrous objects of Baalism in response, so that Baalism becomes an example of any idolatrous cult. Joash as the representativeof Baalism specifies the defined theme by proposing that whichever god demonstrateshis divine power shall be recognised as god. The following episodesof the battle against the Midianites contrast Gideon's inadequateresources with his selfish attempt to be honoured for the victory, assignthe victory to YHWH,who remains in control and who thus demonstrateshis divine power, and show that Baal is not presentin the narrative. -

“Access”: Rhetorical Cartographies of Food

TROUBLING “ACCESS”: RHETORICAL CARTOGRAPHIES OF FOOD (IN)JUSTICE AND GENTRIFICATION by CONSTANCE GORDON B.A., San Francisco State University, 2011 M.A., University of Colorado Boulder, 2015 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Communication 2018 ii This dissertation entitled: Troubling “Access”: Rhetorical Cartographies of Food (In)Justice and Gentrification written by Constance Gordon has been approved for the Department of Communication Phaedra C. Pezzullo, Ph.D. (Committee Chair) Karen L. Ashcraft, Ph.D. Joe Bryan, Ph.D. Lisa A. Flores, Ph.D. Tiara R. Na’puti, Ph.D. Peter Simonson, Ph.D. Date The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB Protocol #17-0431 iii Gordon, Constance (Ph.D., Communication) Troubling “Access”: Rhetorical Cartographies of Food (In)Justice and Gentrification Dissertation directed by Professor Phaedra C. Pezzullo ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the rhetorical and spatiotemporal relationships between food politics and gentrification in the contemporary U.S. developing city foodscape. Specifically, I explore a seemingly innocent, yet incredibly powerful key term for the food movement today: “access.” The concern over adequate food access for the food insecure has become a national conversation, as everyone from governments to corporations, non-profits to grassroots advocates, have organized interventions to bring healthy food to those most in need. In rapidly developing cities, however, these politics have become particularly complicated, as new food amenities often index or contribute to gentrification, including the displacement of the very people supposedly targeted for increased food access. -

Farmers Get Creative with Wet Fields Former Howe Fire the Last Week of May

School board Hoops Camp Steve Bannon’s INSIDE War Room has Summer Library info, pg. 6 to hold coming to become home Community Pep Rally, pg. 8 special Howe for base for former Sports Camp Info, pg. 8 Chamber events, pg. 11 meeting 20th time Fox News viewers Hot Jobs, pg. 12 Texas History, pg. 13 A Special Meet- This year’s camp The moment Fox Christian, pg. 14 ing of the Board will be June 28— News called Finance/Children, pg. 15 of Trustees of July 1 Arizona World Awakening, pg. 17 Past front pages, pg. 20-28 Page 8 Pages 8 Page 16 Grayson Publishing, LLC © 2021 The Howe Enterprise Volume 59, Edition 4 Monday, June 7, 2021 Subscribe for free $0.00—online only Farmers get creative with wet fields Former Howe Fire the last week of May. Chief dies Local farmers in the area are in need of a The good people at few weeks of dry Sonic of Howe tell us weather to get into the that they will be crop fields. That is, closed June 14-17 for unless you’re a crea- floor repair. So don’t tive farmer. Scott panic and help culti- Renfro last week vate those small town hired Whitlock Aerial vicious rumors. Applicators to fly ***** planes to spray ferti- Cause for concern— lizers on the corn the same people that (Continued on page 12) Jerry Park died Tues- told us Trump collud- day after a long battle ed with Russia and Tracks were placed on combines last week from the effects of strong-armed a in order to get into the wet wheat fields. -

Stallion Synopsis For: Instagrand

STALLION SYNOPSIS FOR: INSTAGRAND PREPARED BY: ALAN PORTER PREPARED FOR: PM ADVERTISING LLC Pedigree Consultants are able to help you in all facets of your thoroughbred investment. Not only are we able to proven mating advice but we are also able to advise on mare selection, management and promotion of stallions, and selection and purchase of racing and breeding stock. For more information on the services visit www.pedigreeconsultants.com, email [email protected] or call +1 859 285 0431. INSTAGRAND A $1,2,000,000 two-year-old in training purchase, Instagrand was a debut winner by 10 lengths going five furlongs in 56:00, and followed up with 10¼ lengths victory in the Best Pal Stakes (G2), demonstrating himself to be one of the most spectacular juvenile colts to represent the sensational Leading Sire, and twice Leading Sire of Two-Year-Olds, Into Mischief. Into Mischief has sired the brilliant Goldencents out of a mare by Banker’s Gold, and four stakes winners, including multiple grade one winner Practical Joke, out of mares by Distorted Humor (sire of Flower Alley, Sharp Humor, Drosselmeyer, Maclean’s Music and Jimmy Creed). Banker’s Gold and Distorted Humor are both sons of Forty Niner, a stallion who could also be introduced through mares by Coronado’s Quest, Editor’s Note, End Sweep, Jules, Luhuk, Gold Fever, Roar (broodmare sire of an Into Mischief stakes winner), Trippi (broodmare sire of an Into Mischief graded winner) and Twining. The Into Mischief cross with mares from the Gone West branch of Mr. Prospector has also been a very successful one. -

Setting the Standard

SETTING THE STANDARD A century ago a colt bred by Hamburg Place won a trio of races that became known as the Triple Crown, a feat only 12 others have matched By Edward L. Bowen COOK/KEENELAND LIBRARY Sir Barton’s exploits added luster to America’s classic races. 102 SPRING 2019 K KEENELAND.COM SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 102 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-102.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland Sir Barton, with trainer H. Guy Bedwell and jockey John Loftus, BLOODHORSE LIBRARY wears the blanket of roses after winning the 1919 Kentucky Derby. KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2019 103 SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 103 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-103.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland SETTING THE STANDARD ir Barton is renowned around the sports world as the rst Triple Crown winner, and 2019 marks the 100th an- niversary of his pivotal achievement in SAmerican horse racing history. For res- idents of Lexington, Kentucky — even those not closely attuned to racing — the name Sir Barton has an addition- al connotation, and a local one. The street Sir Barton Way is prominent in a section of the city known as Hamburg. Therein lies an additional link with history, for Sir Barton sprung from the famed Thoroughbred farm also known as Hamburg Place, which occupied the same land a century ago. The colt Sir Barton was one of four Kentucky Derby winners bred at Hamburg Place by a master of the Turf, one John E. Madden. Like the horse’s name, the name Madden also has come down through the years in a milieu of lasting and regen- erating fame. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

News Release ______

News Release _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Darren Rogers Senior Director, Communications & Media Services Churchill Downs Racetrack (502) 636-4461 (office) (502) 345-1030 (mobile) [email protected] SECRETARIAT MADE 7-2 FAVORITE IN KENTUCKY DERBY: TRIPLE CROWN SHOWDOWN LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Wednesday, April 29, 2020) – Secretariat, considered by many as the most talented and iconic Thoroughbred to have raced in America, has been established as the horse to beat in Saturday’s Kentucky Derby: Triple Crown Showdown by veteran odds maker Mike Battaglia. The Kentucky Derby: Triple Crown Showdown is an animated race created by Inspired Entertainment Inc. using computer-generated imagery that will feature the 13 past Triple Crown winners in a 1 ¼-mile race at historic Churchill Downs. The virtual race will be included in NBC’s broadcast of “The First Saturday In May: American Pharoah’s Run to the Triple Crown,” that airs Saturday (May 2) from 3-6 p.m. ET. The Kentucky Derby: Triple Crown Showdown will air in its entirety during the broadcast at approximately 5:45 p.m. ET. Secretariat, the two-time Horse of the Year who swept the 1973 Triple Crown with a stirring 31-length romp in the Belmont Stakes, landed post position No. 3 in a random draw for the field of 13 legends and was made the 7-2 morning line favorite. Calumet Farm’s multiple champion Citation, who won 27 of 29 races at age 2 and 3 including a sweep of the 1948 Triple Crown, is the 4-1 second choice with Seattle Slew and Affirmed, the 1977-78 Triple Crown winners, respectively, each listed at 5-1. -

New Jersey Farm Was a Racing Power for Generations

Brookdale Memories New Jersey farm was a racing power for generations By Cindy Deubler avid Dunham Withers was attracted to the fertile river-fed farmland of Lincroft, N.J., and created DBrookdale Farm in the 1870s. Philanthropist Geraldine TION C Thompson saw her home as one that should be shared with COLLE M TE S others, and in the late 1960s bequeathed a substantial portion of what was once one of the greatest farms in North America OUTH COUNTY PARK SY OUTH COUNTY PARK M to Monmouth County to be used as a park. MON 22 Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred SEPTEMBER 2013 Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred SEPTEMBER 2013 23 TION C COLLE M TE S OUTH COUNTY PARK SY OUTH COUNTY PARK M MON With no horse in sight (other than the nation’s best stallions, boasted the finest America’s leading turfmen Withers’ land purchases from 1872 to the Withers-bred Golden Rod. The stable February 1896 – he was only 59 – it came occasional riding horse), Thompson Park – bloodlines in its broodmare band, and 1888 expanded the farm to 838 acres, and included a juvenile colt Thompson named as a huge blow to the industry. The stable the former Brookdale Farm – stands as a provided a superb training facility utilized D.D. Withers created it, Colonel William he oversaw every detail, including layout The Sage, in honor of Brookdale’s creator. was taken over by his sons, Lewis S. and glorious link to New Jersey’s golden age in by industry giants named Withers, Keene P. Thompson had great plans for it, legend- and construction. -

Maryland Horse Breeders Association

Maryland Horse M A Breeders Association RYL Officers Joseph P. Pons Jr. A President ND Donald H. Barr Vice-President Milton P. Higgins III Secretary-Treasurer Board of Directors Donald H. Barr Richard F. Blue Jr. R. Thomas Bowman* Maryland Horse Rebecca B. Davis John C. Davison David DiPietro James T. Dresher Jr. Breeders Association Michael J. Harrison Milton P. Higgins III R. Larry Johnson he Maryland Horse Breed- horse enthusiasts of all kinds. Maryland’s Day at the Races; and Edwin W. Merryman ers Association (MHBA) The MHBA publishes a weeklye mdthoroughbredhalloffame.com Wayne L. Morris* Thas been the leading horse e-mail bulletin and a monthly which showcases full biographies Suzanne Moscarelli industry advocate in the state newsletter, Maryland Horse, as of the Maryland-bred Hall of since its founding in 1929. It well as Mid-AtlanticThoroughbred Fame horses. Tom Mullikin functions as an informational magazine. The MHBA helped innovate, Joseph P. Pons Jr. resource for horse breeders In addition, the MHBA main- and now administers, several William S. Reightler Jr. and owners, for the media, for tains several websites: Maryland state-oriented incentive pro- Robert B. White national, community and gov- Thoroughbred.com, a resource grams. Both the Maryland-Bred *president appointment ernmental organizations and for for news and information on Race Fund, created by statute in Cricket Goodall the general public. Maryland breeding and racing; 1962 for Thor oughbreds foaled Executive director As a service organization, the MidAtlanticTB.com, which car- in Mary land, and the Maryland MHBA provides industry infor- ries regional news, information Million, chartered in 1985 for P.O. -

ACORN to MIGHTY OAK Juvenile Group 1 Winner, from Robert Sangster

WAR OF WILL: ACORN TO MIGHTY OAK juvenile Group 1 winner, from Robert Sangster. "Callan and his team have reared a lot of good horses for the By Chris McGrath family," recalls Alan Cooper, the Niarchos family's long-serving Callan Strouss has just ended a call with Maria Niarchos, about racing manager. "And that continuity of management is the party she's throwing for his team at the Oak Tree division of essential: you get to know the traits of the bloodline, and that Lane's End. Just her way of thanking everyone who raised a colt you can forgive a certain imperfection, if it's in the family and that has broken new ground, even for the storied Flaxman they've still won Group 1 races." Holdings program, by graduating to win an American Classic. War Of Will would never even have been entered for the 2017 And now Strouss, picking up the receiver again, finds himself Keeneland September Sale had he been a filly. His dam Visions asked to put it all into words. Of Clarity (Sadler's Wells) "I'm sitting in my office, was admittedly one of looking at a picture," he only two stakes winners replies. "You'll know out of Aviance's Group about Aviance. Well, to 1-placed daughter her left is Lingerie. And to Imperfect Circle her right is Miesque. Now (Riverman)--but the other isn't that incredible, to was the charismatic have worked with those champion miler Spinning kind of families? With War World (Nureyev). So her Of Will, you're going back 2016 son only went under to Best In Show.