Impact of the Enlargement of the European Union on Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly 3 · 2009

cover_GFQ_3_2009heller.qxp:cover_GFQ_3_2009heller 24.07.2009 15:06 Uhr Seite 1 German Films Quarterly 3 · 2009 AT LOCARNO THE TWO HORSES OF GENHIS KHAN by Byambasuren Davaa AT MONTREAL ALIAS by Jens Junker ANNE PERRY-INTERIORS by Dana Linkiewicz CEASEFIRE by Lancelot von Naso AT VENEDIG DESERT FLOWER by Sherry Hormann SOUL KITCHEN by Fatih Akin PORTRAITS Almut Getto, Niko von Glasow, UFA Cinema, Alice Dwyer Inhaltsverz_GFQ3_2009.qxp:Inhaltsverz_GFQ3_2009 24.07.2009 15:01 Uhr Seite 1 German Films Quarterly 3 · 2009 directors’ portraits 4 A STROKE OF LUCK A portrait of Almut Getto 6 SHAKING AND STIRRING A portrait of Niko von Glasow producers’ portrait 8 NEW KIDS ON THE BLOCK A portrait of UFA Cinema actress’ portrait 12 SENSUALITY WITH PRINCIPLES A portrait of Alice Dwyer 14 news in production 18 BIS AUFS BLUT Oliver Kienle 18 BLACK DEATH Christopher Smith 20 FRECHE MAEDCHEN 2 Ute Wieland 20 GLUECKSRITTERINNEN Katja Fedulova 21 HABERMANN Juraj Herz 22 DER HUNGERWINTER 1946/47 Gordian Maugg 23 DIE JAGD NACH DER HEILIGEN LANZE Florian Baxmeyer 24 LUKS GLUECK Ayse Polat 25 NANGA PARBAT Joseph Vilsmaier 26 ORIENT EXPRESS THEATRE TRAIN Martin Andersson, Steffen Duevel 27 ORLY Angela Schanelec 27 RUMPE & TULI Samy Challah, Till Nachtmann, Stefan Silies 29 DER SANDMANN Jesper Moeller, Sinem Sakaoglu, Helmut Fischer 30 SATTE FARBEN VOR SCHWARZ Sophie Heldman 31 DAS SCHWEIGEN Baran bo Odar 32 THEMBA Stefanie Sycholt new german films 34 ALIAS Jens Junker 35 ANNE PERRY – INTERIORS Dana Linkiewicz 36 AYLA Su Turhan Inhaltsverz_GFQ3_2009.qxp:Inhaltsverz_GFQ3_2009 24.07.2009 15:01 Uhr Seite 2 37 BERLIN ’36 Kaspar Heidelbach 38 CHI L’HA VISTO Claudia Rorarius 39 DEUTSCHLAND NERVT MADE IN DEUTSCHLAND Hans-Erich Viet 40 DER ENTSORGTE VATER THE DISCARDED FATHER Douglas Wolfsperger 41 FLIEGEN FLY Piotr J. -

The Austrian Imperial-Royal Army

Enrico Acerbi The Austrian Imperial-Royal Army 1805-1809 Placed on the Napoleon Series: February-September 2010 Oberoesterreicher Regimente: IR 3 - IR 4 - IR 14 - IR 45 - IR 49 - IR 59 - Garnison - Inner Oesterreicher Regiment IR 43 Inner Oersterreicher Regiment IR 13 - IR 16 - IR 26 - IR 27 - IR 43 Mahren un Schlesische Regiment IR 1 - IR 7 - IR 8 - IR 10 Mahren und Schlesischge Regiment IR 12 - IR 15 - IR 20 - IR 22 Mahren und Schlesische Regiment IR 29 - IR 40 - IR 56 - IR 57 Galician Regiments IR 9 - IR 23 - IR 24 - IR 30 Galician Regiments IR 38 - IR 41 - IR 44 - IR 46 Galician Regiments IR 50 - IR 55 - IR 58 - IR 63 Bohmisches IR 11 - IR 54 - IR 21 - IR 28 Bohmisches IR 17 - IR 18 - IR 36 - IR 42 Bohmisches IR 35 - IR 25 - IR 47 Austrian Cavalry - Cuirassiers in 1809 Dragoner - Chevauxlégers 1809 K.K. Stabs-Dragoner abteilungen, 1-5 DR, 1-6 Chevauxlégers Vienna Buergerkorps The Austrian Imperial-Royal Army (Kaiserliche-Königliche Heer) 1805 – 1809: Introduction By Enrico Acerbi The following table explains why the year 1809 (Anno Neun in Austria) was chosen in order to present one of the most powerful armies of the Napoleonic Era. In that disgraceful year (for Austria) the Habsburg Empire launched a campaign with the greatest military contingent, of about 630.000 men. This powerful army, however, was stopped by one of the more brilliant and hazardous campaign of Napoléon, was battered and weakened till the following years. Year Emperor Event Contingent (men) 1650 Thirty Years War 150000 1673 60000 Leopold I 1690 97000 1706 Joseph -

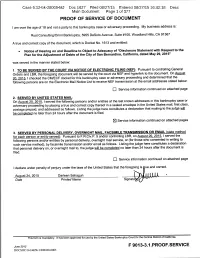

Case 6:12-Bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27

Case 6:12-bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 377 Case 6:12-bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 377 City of San BernardinoCase 6:12-bk-28006-MJ - U.S. Mail Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 DescServed 8/20/2015 Main Document Page 3 of 377 @COMM DEPARTMENT 05321 100 PLAZA CLINICAL LAB INC 1458 - CELPLAN TECHNOLOGIES, INC. P O BOX 39000 100 UCLA MEDICAL PL 245 1920 ASSOCIATION DRIVE, 4TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94139-5321 LOS ANGELES, CA 90024-6970 RESTON, VA 20191 3M CUSTOMER SERVICE A & G TOWING A & R LABORATORIES INC 2807 PAYSPHERE CIR 591 E 9TH ST 1401 RESEARCH PARK DR 100 CHICAGO, IL 60674 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92410 RIVERSIDE, CA 92507 A & W EMBROIDERY A 1 AUTO GLASS A 1 BUDGET GLASS P O BOX 10926 671 VALLEY BL 705 S WATERMAN AV SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92423 COLTON, CA 92324 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 A 1 BUDGET HOME & OFFICE CLEANING A 1 EVENT & PARTY RENTALS A 1 TREE SERVICE 2889 N GARDENA ST 251 E FRONT ST 304 E CLARK SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92407-6633 CORONA, CA 91723 REDLANDS, CA 92373 A A EQUIPMENT RENTAL A AMERICAN SELF STORAGE A G ENGINEERING 4811 BROOKS ST 875 E MILL ST 8647 HELMS AV MONTCLAIR, CA 91763 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CA 91730 A GRAPHIC ADVANTAGE A J JEWELRY A J O CONNOR LADDER 3901 CARTER AV 2 1292 W MILL ST 103 4570 BROOKS RIVERSIDE, CA 92501 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92410-2500 MONTCLAIR, CA 91763 A K ENGINEERING A L WARD A PLUS AUTOMOTIVE INC 1254 S WATERMAN AV 17 ADDRESS REDACTED A PLUS SMOG AND MUFFLER SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 235 E HIGHLAND SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92404 A PLUS COURT REPORTERS INC A T & T A T S I 35 E UNION ST A 1265 VAN BUREN 180 8157 US HIGHWAY 50 PASADENA, CA 91103 ANAHEIM, CA 92807 ATHENS, OH 45701 A T SOLUTIONS INC A T SOLUTIONS INC. -

1980 WORLD MEN LIST Developed by Pino Mappa with Assistance Of: Richard Hymans, Børre Lilloe, Gabriele Manfredini, Enzo Rivis

1980 WORLD MEN LIST Developed by Pino Mappa with assistance of: Richard Hymans, Børre Lilloe, Gabriele Manfredini, Enzo Rivis 100 METRES James SANFORD USA 27 Dec 57 183/78 10.02 1.0 1 Pepsi Westwood CA 11 May James SANFORD (2) A 10.03 1.6 1 El Paso TX 19 Apr Stanley FLOYD USA 23 Jun 61 178/74 10.07 2.0 1 Austin TX 24 May James SANFORD (3) 10.10 0.5 1 Pac Seattle WA 24 May Stanley FLOYD (2) 10.10 1.1 1 NCAA Austin TX 06 Jun Allan WELLS GBR 03 May 52 183/83 10.11 1.4 1 q1 OG Moskva 24 Jul Mike ROBERSON USA 25 Mar 56 175/66 10.12 1.1 2 NCAA Austin TX 06 Jun James SANFORD (4) 10.12 1.1 3 NCAA Austin TX 06 Jun Stanley FLOYD (3) 10.12 1.2 1 Den Haag 04 Jul Petar PETROV BUL 17 Feb 55 180/80 10.13 1.4 2 q1 OG Moskva 24 Jul (10) Stanley FLOYD (4) 10.13 0.4 1 Luxembourg 29 Aug Harvey GLANCE USA 28 Mar 57 171/67 10.14 2.0 1 s2 FOT Eugene OR 22 Jun Mel LATTANY USA 10 Aug 59 175/79 10.14 0.0 1 MdR Rieti 31 Aug Silvio LEONARD CUB 20 Sep 55 180/65 10.15 1.8 1 PTS Bratislava 06 Jun Silvio LEONARD (2) 10.16 0.2 1 q2 OG Moskva 24 Jul Stanley FLOYD (5) 10.16 0.0 1 Eight Nat Tokyo 20 Sep Stanley FLOYD (6) 10.17 2.0 1 h1 SEC Auburn AL 17 May Calvin SMITH USA 08 Jan 61 178/69 10.17 2.0 2 Austin TX 24 May Calvin SMITH (2) 10.17 1.1 4 NCAA Austin TX 06 Jun Eugen RAY † GDR 26 Jul 57 183/89 10.18 0.5 1 h1 OT Potsdam 10 May (20) Eugen RAY (2) 10.18 1.8 1 OT Potsdam 10 May Jerome DEAL USA 24 Mar 58 183/79 10.18 2.0 3 Austin TX 24 May Mike ROBERSON (2) 10.19 0.8 1 Tallahassee FL 15 Mar Hasely CRAWFORD TTO 16 Aug 50 190/87 10.19 1 Caracas 09 May Marian WORONIN POL -

Newsletter B10/N.26 1 June 2010

Newsletter B10/n.26 1 June 2010 1 26 July - 1 August Barcelona 2010 thrills with cinema commercial bcn2010.org Manolo Martinez (left), Naroa Agirre and Jackson Quiñonez (below) star in the Barcelona 2010 commercial On 19 May, from dawn to dusk, seven of the main Spanish athletes participated in a commercial for the European Athletics Championships Barcelona 2010. The Montjuïc Olympic Stadium was the stage for this long day, which had more to do with cinema than athletics. In the commercial, designed by the agency Villarosàs (the successful bidder in the tender organised), Naroa Agirre, Concha Montaner, Jackson Quiñónez, Reyes Estévez, Juan Carlos Higuero, Ángel David Rodríguez and Manolo Martínez illustrate, with carefully composed shots, that what seems easy from a distance is not when viewed close up. This is the commercial’s message. Athletics is not an easy sport and not everyone dares to Pole Vault or Shot Put. More than 150 volunteers participated in the shooting as extras. For a few hours the Olympic Stadium became a film set, and the popular band “Love of Lesbian” played the commercial’s soundtrack, called “Incondicional”. The commercial will be broadcast on several TV channels during the month prior to the start of the European Athletics Championships Barcelona 2010, from 21 June. The commercial will be the main feature of the final Barcelona 2010 promotional campaign. This television promotion campaign will be added to the more traditional campaigns used previously, in order to reach as many fans as possible. Buy your event pass now! Visit servicaixa.com For more information consult our website: www.bcn2010.org Newsletter B10/n.26 1 June 2010 2 26 July - 1 August 76-year-old Championships bcn2010.org As we do not have a poster of the men´s European Athletics Championships of 1938 (that was the only event where men and women competed separately), in this historical section we present the available graphical elements that were used to promote the previous 19 championships to date. -

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT's Office Files, 1933

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S Office Files, 1933–1945 Part 5: The John Franklin Carter Files on German Nazi Party Members UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S OFFICE FILES, 1933–1945 Part 5: The John Franklin Carter Files on German Nazi Party Members Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide Compiled by Blair D. Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s office files, 1933–1945 [microform]. (Research collections in American politics) Compiled from the papers of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the custody of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library. Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Robert E. Lester and Blair D. Hydrick. Includes indexes. Contents: pt. 1. “Safe” and confidential files— [etc.]—pt. 4. Subject files—pt. 5. The John Franklin Carter files on German Nazi Party members. 1. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882–1945—Archives. 2. Franklin D. Roosevelt Library— Archives. 3. United States—Politics and government— 1933–1945—Sources. 4. United States—Foreign relations— 1933–1945—Sources. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882–1945. IV. United States. President (1933–1945 : Roosevelt) V. Franklin D. -

The Learning Region

DOCUMENT RESUME CE 085 377 ED 479 670 AUTHOR Guggenheim, Eric Fries, Ed. Agora XI: The LearningRegion (Thessaloniki, Greece, March TITLE 15-16, 2001). CEDEFOP PanoramaSeries. Development of Vocational Training, INSTITUTION European Centre for the Thessaloniki (Greece). REPORT NO TI-49-03-894-EN-C; CEDEFOP-70 ISBN ISBN-92-896-0221-X ISSN ISSN-1562-6180 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 and Portuguese. NOTE 166p.; Also available in French GR-55102 Greece. Tel: 30 AVAILABLE FROM CEDEFOP, PO Box 22427, Thessaloniki, 31 49 01 11; Fax: 30 31 49 01 02;e-mail: [email protected]; Web site:http://www.trainingvillage.gr/ (# 5140 EN, free). For full text: http://www2.trainingvillage.gr/ etv/publication/download/panorama/ 5140_en.pdf. PUB TYPE Collected Works Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. Impact; *Educational DESCRIPTORS Adoption (Ideas); Colleges; Economic Innovation; Foreign Countries; Partnershipsin Education; *Policy Formation; *Regional Cooperation;Regional Programs; School Business Relationship; SocialCapital; *Social Integration; *Vocational Education;Vocational Schools; Vocational Training Centers Regions IDENTIFIERS *Europe; European Union; *Learning ABSTRACT This conference program describes"education and training agencies taking a leading rolein promoting innovation on a regionalbasis" following three key issues to as the focus ofthe Agora and puts forward the region itself and a be debated during it:(1) the concept of the learning critique of its strengths andweaknesses;(2) education and training agencies, including -

Athens & Epidaurus Festival 2019 Artistic Director

1 ATHENS & EPIDAURUS FESTIVAL 2019 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Vangelis Theodoropoulos BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT Petros Stavrianos VICE PRESIDENT Eleftheria Raptou MEMBERS Nikos Erinakis Martha Fosteri George Kouroupos Vassilis Lambrinoudakis Effi Yannopoulou ARTISTIC CO-CURATORS Carolin Hochleichter – International productions Grorgina Kakoudaki – Educational programmes Dimitra Kondylaki – Contemporary Greek theatre Costa Pilavachi – Music Steriani Tsintziloni – Dance 2 Athens & Epidaurus Festival 2019 EPIDAURUS ODEON OF HERODES ATTICUS Robert Wilson, Oedipus Greek National Opera – Carlus Padrissa – La Fura dels Baus – Georgios Ballatsinos, Norma NATIONAL THATRE OF GREECE by Bellini Oresteia by Aeschylus Io Voulgaraki, Agamemnon Eleni Karaindrou, Tous des oiseaux Lilly Meleme, The Libation Bearers Georgia Mavragani, The Eumenides Jethro Tull, 50 years of Jethro Tull NATIONAL THEATRE OF GREECE Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg – CYPRUS THEATRE ORGANISATION Yuja Wang – Gustavo Gimeno Stathis Livathinos, The Suppliants by Euripides George Dalaras – İzmir State Symphony Orchestra Κ. Markoulakis, Oedipus Rex by Sophocles – Hakan Sensoy NATIONAL THEATRE OF NORTHERN GREECE ERT National Symphony Orchestrra – Anastasios Yannis Kalavrianos, Symeonidis, Fête de la musique Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Wiener Symphoniker – Leonidas Kavakos COMÉDIE-FRANÇAISE Ivo van Hove, Electra / Orestes by Euripides Athens State Orchestra A Tribute to Steven Spielberg Dimitris Karantzas, The Clouds by Aristophanes Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra - Zoi Stavros -

100 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft Für Materialkunde 1919-2019

Helmut Maier 100 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Materialkunde Bochumer Studien zur Technik- und Umweltgeschichte herausgegeben von Helmut Maier Band 11 In den ersten Jahrzehnten des 20. Jahrhunderts standen die Taten »großer Inge- nieure«, später auch die technischen Entwicklungen der Industrieunternehmen im Fokus der Technikgeschichte. Der Direktor des VDI, Conrad Matschoß (1871–1942), bemühte sich um ihre Etablierung an den Technischen Hochschulen. Ab den 1960er Jahren wandelte sich die Technikgeschichte zur historischen Disziplin, die Ursa- chen und Folgen der Technik in ihrem sozio-ökonomischen Kontext zu analysieren suchte. Sichtbarer Ausdruck dieses Wandels war die Gründung des Lehrstuhls für Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte an der Fakultät für Geschichtswissenschaft der Ruhr-Universität Bochum im Jahre 1966. Die Herausbildung der Umweltgeschichte als historische Teildisziplin ab den 1980er Jahren war vor allem der Technikgeschichte zu verdanken. Die Umweltge- schichte profitierte vom Aufstieg des Problemkomplexes Umwelt im gesellschafts- politischen Diskurs. Noch stärker als die Technikgeschichte versteht sich die Umweltgeschichte an den Hochschulen heute als Brückenfach zwischen den Tech- nik-, Natur- und Geisteswissenschaften. Die Ruhr-Universität Bochum trug dieser Entwicklung mit der Umwidmung der Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte zur Tech- nik- und Umweltgeschichte im Jahre 2006 Rechnung. Die Bochumer Reihe zur Technik- und Umweltgeschichte führt historische Stu- dien zusammen, die dem Charakter der Disziplin als multidisziplinärem Brücken- fach entsprechend auch wissenschafts- und wirtschaftshistorische Fragestellungen bearbeiten. Dazu zählen nicht nur an der Ruhr-Universität Bochum entstandene qualifizierende Arbeiten, sondern auch solche mit regionalem Fokus auf das Ruhr- gebiet. Hinzu kommen Studien und Tagungsbände, die aus der Kooperation des Lehrstuhls für Technik- und Umweltgeschichte mit anderen Institutionen sowie aus dem weiteren Umfeld der historischen Ausschüsse der technisch-wissenschaftlichen Vereine hervorgehen. -

FRATERNITÉ, Conte Fantastique by Caroline Guiela Nguyen (Brotherhood, a Fantastic Tale)

PRESS RELEASE PROSPERO _Extended Theatre gathers 10 partners - 9 theatres and one Media group (ARTE), from 9 countries of the Union. The project was built around a new dynamic of collaborations, synergies and relationships between the partners, their respective teams, the artists and the audiences around the redesign of the production and distribution of the shows. THE PROJECT HAS THREE MAIN GOALS: _ To imagine other principles, other developments for a more inclusive, more diversified European theatre creation, more connected to current societal issues; _ Broaden the dissemination of theatrical works, in theatres and on the digital space, to reach new audiences; _ Rethink the theatrical journey of audiences, from the initial discovery to the aftermath of the performance. In this context of repeated crises, which confronts Europe with the need to convince its citizens, the partners intend to show that art and culture are a powerful force capable of stimulating creativity, exchange and cohesion. They believe that theatre, in particular, remains an essential place for dialogue, capable of creating real, direct, human encounters and of increasing our critical sense. Through their work, they wish to participate in the artistic and cultural development of Europe. Thanks to the support of the Creative Europe programme, the partners, strengthened by their visibility at the European level and their openness to other continents, are able to pursue their research on the issues of theatre, media and creation, more particularly their evolution and modernization. THE PARTNERS Théâtre de Liège (lead partner – Belgique) supported by Wallonia-Brussels International Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione (Modena– Italia) São Luiz Teatro Municipal (Lisboa – Portugal) Göteborgs Stadsteater (Göteborg - Sverige) Hrvatsko narodno kazalište u Zagrebu (Zagreb – Hrvatska) Teatros del Canal – Comunidad de Madrid (España) Schaubühne Berlin (Deutschland) Teatr Powszechny (Warszawa – Polska) Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe (Paris – France) ARTE THREE RESEARCH CLUSTERS 1. -

Banaters in the Xii Deutsch Banater Grenz Regiment Records

BANATERS IN THE XII DEUTSCH BANATER GRENZ REGIMENT RECORDS David Dreyer 808 N Claremont San Mateo, Calif 94401 USA September 2021 Final Draft BANATERS IN THE XII DEUTSCH BANATER GRENZ REGIMENT RECORDS The author acknowledges an immense debt to Anton Kramer (*1926, +2010) for his generous aid, penetrating insight and continuous encouragement in Banat matters. Thanks are due to David and Karen Preston for their trouble shooting and indispensable aid in managing files. aaaaaa Whenever mentioned in this document, the reader is encouraged to review the Film Number (Family History Library) for further details in the records transcribed herein. It is free to join. Go to https://www.familysearch. org/catalog/ , click on the Film/Fiche Number link and enter the film number into the drop-down. You can then see the complete information that was not all extracted for this work. Examples are given in the Appendices. This work represents many years of research and goals that had morphed over those years. Therefore, there may be overlapping information presented in different sections of this document. Research can often influence the direction and depth of the endeavor. "Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose."1 1 Zora Neale Hurston, Anthropologist (1891-1960) Banaters in the XII Grenz Regiment Records Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The Austrian Military Frontier 5 The Banat Military Frontier 6 ENROLLMENT OF MANPOWER TO THE REGIMENT 7 1773 MUSTER LISTS OF DEUTSCH BANATER COMPANIES 8 1773 MUSTER LISTS BY PLATZ -

University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Yearbooks & Class Year Publications Law School History and Publications Class of 1954 The Quad Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/class_pubs Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation "The Quad" (1954). Yearbooks & Class Year Publications. 170. https://repository.law.umich.edu/class_pubs/170 This Yearbook is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yearbooks & Class Year Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r We proud!) cledicate the 19!i4 Qunrl to an Olll· standing legal schol:ir. R11l/1li II'. Aigln. University of Michigan law School Ann Arbor .·::. Michigan The focal point o[ the Law Quad, the Legal Research Build ing serves the legal scholar with 236,651 bound volumes, a read ing room with a seating capacity ol 500 persons and various other offices. Open stacks featuring federal and state reports, reg ional reporters, current statutes, English Reports, dictionaries and citators are part of the many advantages offered Hutchins Hal1, named m honor of Harry B. Hntchjns, Dean of the Law School from 1895 to l910, serves mainly as a classroom building. In ad<lilion to its njne classrooms, it contains, a Prac tice Courtroom, faculty and adminis trative offices, a faculty library and study room and the Alumni Room. DOCKET l Dedication 7 Faculty Organizations 19 Student Body 37 FACULTY / ) I E.