Temporal and Spatial Trends in Stranding Records of Cetaceans on the Irish Coast, 2002–2014 Barry Mcgovern1,2, Ross M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2010) Records from the Irish Whale

INJ 31 (1) inside pages 10-12-10 proofs_Layout 1 10/12/2010 18:32 Page 50 Notes and Records Cetacean Notes species were reported with four sperm whales, two northern bottlenose whales, six Mesoplodon species, including a True’s beaked whale and two Records from the Irish Whale and pygmy sperm whales. This year saw the highest number of Sowerby’s beaked whales recorded Dolphin Group for 2009 stranded in a single year. Records of stranded pilot whales were down on previous years. Compilers: Mick O’Connell and Simon Berrow A total of 23 live stranding events was Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, recorded during this period, up from 17 in 2008 Merchants Quay, Kilrush, Co. Clare and closer to the 28 reported in 2007 by O’Connell and Berrow (2008). There were All records below have been submitted with however more individuals live stranded (53) adequate documentation and/or photographs to compared to previous years due to a two mass put identification beyond doubt. The length is a strandings involving pilot whales and bottlenose linear measurement from the tip of the beak to dolphins. Thirteen bottlenose dolphin strandings the fork in the tail fin. is a high number and it includes four live During 2009 we received 136 stranding stranding records. records (168 individuals) compared to 134 records (139 individuals) received in 2008 and Fin whale ( Balaenoptera physalus (L. 1758)) 144 records (149 individuals) in 2007. The Female. 19.7 m. Courtmacsherry, Co. Cork number of stranding records reported to the (W510429), 15 January 2009. Norman IWDG each year has reached somewhat of a Keane, Padraig Whooley, Courtmacsherry plateau (Fig. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Appendix B. List of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas

Appendix B. List of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas Irish Water | Draft Framework Plan. Natura Impact Statement Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) in the Republic of Ireland Site code Site name 000006 Killyconny Bog (Cloghbally) SAC 000007 Lough Oughter and Associated Loughs SAC 000014 Ballyallia Lake SAC 000016 Ballycullinan Lake SAC 000019 Ballyogan Lough SAC 000020 Black Head-Poulsallagh Complex SAC 000030 Danes Hole, Poulnalecka SAC 000032 Dromore Woods and Loughs SAC 000036 Inagh River Estuary SAC 000037 Pouladatig Cave SAC 000051 Lough Gash Turlough SAC 000054 Moneen Mountain SAC 000057 Moyree River System SAC 000064 Poulnagordon Cave (Quin) SAC 000077 Ballymacoda (Clonpriest and Pillmore) SAC 000090 Glengarriff Harbour and Woodland SAC 000091 Clonakilty Bay SAC 000093 Caha Mountains SAC 000097 Lough Hyne Nature Reserve and Environs SAC 000101 Roaringwater Bay and Islands SAC 000102 Sheep's Head SAC 000106 St. Gobnet's Wood SAC 000108 The Gearagh SAC 000109 Three Castle Head to Mizen Head SAC 000111 Aran Island (Donegal) Cliffs SAC 000115 Ballintra SAC 000116 Ballyarr Wood SAC 000129 Croaghonagh Bog SAC 000133 Donegal Bay (Murvagh) SAC 000138 Durnesh Lough SAC 000140 Fawnboy Bog/Lough Nacung SAC 000142 Gannivegil Bog SAC 000147 Horn Head and Rinclevan SAC 000154 Inishtrahull SAC 000163 Lough Eske and Ardnamona Wood SAC 000164 Lough Nagreany Dunes SAC 000165 Lough Nillan Bog (Carrickatlieve) SAC 000168 Magheradrumman Bog SAC 000172 Meenaguse/Ardbane Bog SAC 000173 Meentygrannagh Bog SAC 000174 Curraghchase Woods SAC 000181 Rathlin O'Birne Island SAC 000185 Sessiagh Lough SAC 000189 Slieve League SAC 000190 Slieve Tooey/Tormore Island/Loughros Beg Bay SAC 000191 St. -

Background Enjoy Ireland

BACKGROUND 68 B Special: Book of Kells 75 Irish Literature 14 The Emerald Isle 78 B Special: A Place to Sing 16 Facts 82 Famous People 17 Natural Environment 21 Population • Politics - Economy ENJOY IRELAND 22 D Infographic; Facts & Figures 94 Accommodation 24 B Welcom to Everyday Life 95 A Bed for Every Budget 32 Language 96 B Special; Like Staying 34 B Infographic: Irish- with Friendst Gaelic Culture 36 Religion 98 Travelling with 38 B Special: Ireland's Patron Children 99 Fun and Excitement are 44 History guaranteed 45 The Long Fight for Freedom 102 Festivals, Holidays 54 B Special: Reconciliation and Events at Last! 103 Lots of Variety 106 B Special: »Treats for 60 Arts and Culture Foodies« 61 Art History 64 B 3D: Testimony to Irish 108 Food and Drink Piety 109 Traditional and Modern 110 H Special: Green Grass, 181 Athlone Yellow Butter 183 Athy 112 H Special:Guinness is Good 185 Ballina for You 188 Ballinasloe 116 D Special: Traditional 189 Ballybunion Dishes 190 Bantry 193 Beara Peninsula 120 Shopping 196 Belfast 121 Ireland to Take Home 216 Birr 122 B Special: From Farm to 218 Blarney Fork! 220 Bloody Foreland 222 Boyle 124 Sport and Outdoors224 Boyne Valley 125 A Sports Loving Island 226 B 3D: Newgrange 126 B Special: »It was this big!« - the Realm of the Dead 130 B Special: »More than 228 Bray Sports« 229 Bundoran 230 Burren 234 Cahir 235 Carlow TOURS 236 B Infographic: Megalith Cultures 138 Tours of Ireland 239 Carrick-on-Shannon 140 Travelling in Ireland 240 Carrick-on-Suir 141 Trail of the Stones 241 Cashel 144 Forests, Monks and Long Beaches 147 Culinary Treats, Cliffs and Heritage 150 Whiskey, Salmon and the Wild West 152 From Sea to Sea SIGHTS FROM A TO Z 158 Achill Island 160 Adare 162 Antrim Coast & Glens 164 Aran Islands 168 Ardara 169 Ardmore 170 Ards Peninsula 174 Arklow 175 Armagh 242 H 3D: Rock of Cashel - As 396 Kilkenny if Raised to the Heaven .. -

National Broadband Plan Ireland’S Broadband Intervention Natura Impact Statement 2018 National Broadband Plan - Intervention Strategy

National Broadband Plan Ireland’s Broadband Intervention Natura Impact Statement 2018 National Broadband Plan - Intervention Strategy Appropriate Assessment Natura Impact Statement October 2018 rpsgroup.com/ireland Natura Impact Statement (NIS) for the National Broadband Plan Intervention Strategy TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 APPROACH TO NIS PREPARATION ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 LAYOUT OF NIS .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.3 LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT FOR APPROPRIATE ASSESSMENT ......................................................................... 2 1.4 PURPOSE OF THE AA PROCESS ......................................................................................................... 3 1.5 OVERLAP WITH THE STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF THE NBP ............................................ 3 1.6 CONSULTATION .............................................................................................................................. 4 2 BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW OF THE NBP INTERVENTION STRATEGY ............................. 9 2.1 NATIONAL BROADBAND PLAN (NBP) ................................................................................................. 9 2.2 NBP INTERVENTION STRATEGY ........................................................................................................ -

Report on the Conservation Value of Irish Coastal Sites: Machair in Ireland

0 REPORT OWN' TOE: CONS-ERVATEON 01IRISH. O.OA;STArL, SITE-S o MAC 1AIR ,.IN. -IRELAND* 9 BY ' NNEBASSETT- vR+,i, 1 I v REPORT ON THE CONSERVATION VALUE OF IRIS? COASTALSITES: MACHAIR IN IRELAND By ANNE BASSETT, B.A. (MOO.), H.Dip.Ed.,Dip.et. app. (Montpellier). REPORT COMPILED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES ANDFORESTRY DECEMBER 1983 lit 3. I . 2 . TABLE OF I CONTENTS Ii-'TRUDUCT10N: nLCln OFTHE SCUTLAi'gD. CiiAi,:ACTEi%1STICS OF IN 1.1 Definitionof eiacnair Page No. 1.2 General 5 1.2.1 PhysicalDackyrouna 1.2.2 uistriDution 6 i . 2.3 Sol.is 7 1.2.4 Ci i,, ate r_orpnoloyy 5 1.2.5 10 12 1.3 human 1.3.1bacKground 1.3.2 ti story 13 Present DayUse -Cultivation, 13 Pasturage,,anagement II ,E` HUDS: 14 SURVEY OFIRISH MACHAIR SITES 15 2.1 General,..ethods 15 2.2 Soils 16 2.3 Climate 16 2.4 Morphology 16 2.5 Veyetation 2.6 16 humanInfluence 17 2.7 Conservation ValueAssessment III 17 RESULTS:SURVEY OF IRISH iACHAIRSITES 3.1 Soils 17 3.2 Climate 18 3.3 Morphology 20 .3.4 VeSetation 3.5 21 HUManInfluence 3.6 23 Discussion ofResults 24 IV DESCRIPTIONS ANDCONSERVATIOt4 VISITED ASSESSMENTSOFSITES 26 GeneralConclusions Bibliography 54 55 Acknowledgements J Tables 1-5 58 59 Appendices1-4 3 . TABLES, FIGURES, PLATES, APPENDICES TABLES 1 . Surt:mary A ofoccurrenceofthe com T,.on si,:eciesfoundort ti,acnair. 2. ph values, percentaue organic;,tatter,depth of humus and percentage CaC03 front 15 ii..acnair sitesin western. Ireland, c(jr:Sistiny of 34 sairil,les, ana from 4 Scottish sites. -

MGE0741RP0007 Addendum to Edge 2D HR Seismic Survey and Site Survey – Screening for EIA and ERA Report Response to RFI F01 21 October 2019

ADDENDUM TO EDGE 2D HR SEISMIC SURVEY AND SITE SURVEY – SCREENING FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR FURTHER INFORMATION 2ND AUGUST 2019 MGE0741RP0007 Addendum to Edge 2D HR Seismic Survey and Site Survey – Screening for EIA and ERA Report Response to RFI F01 21 October 2019 rpsgroup.com RESPONSE TO RFI AND CLARIFICATIONS Document status Review Version Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by date Response to RFI and Gareth Gareth F01 James Forde 21/10/2019 Clarifications McElhinney McElhinney Approval for issue Gareth McElhinney 21 October 2019 © Copyright RPS Group Limited. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Limited no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS Group Limited for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. RPS Group Limited accepts no responsibility for any documents or information supplied to RPS Group Limited by others and no legal liability arising from the use by others of opinions or data contained in this report. It is expressly stated that no independent verification of any documents or information supplied by others has been made. RPS Group Limited has used reasonable skill, care and diligence in compiling this report and no warranty is provided as to the report’s accuracy. -

A Framework for Corncrake Conservation to 2022

A Framework for Corncrake Conservation to 2022 National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage & the Gaeltacht. Version: 03 November 2015 Contents Current status ............................................................................................................ 4 Current factors causing loss or decline ....................................................................... 7 The All-Ireland Species Action Plan .......................................................................... 8 The implementation of Corncrake conservation measures .......................................... 9 Monitoring ...................................................................................................... 10 Corncrake Conservation Schemes .................................................................... 10 Management of land for Corncrakes beyond Corncrake SPAs .......................... 13 Predator control actions for Corncrake conservation ....................................... 14 The Corncrake SPA Network .................................................................................. 14 Activities Requiring Consent in Corncrake SPAs ................................................... 16 Middle Shannon Callows SPA ................................................................................. 16 Moy Valley IBA ...................................................................................................... 17 Targets for SPA population growth and habitat management ................................... 24 10-year -

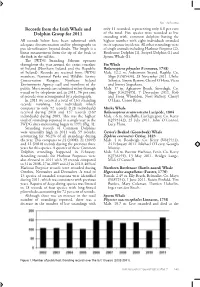

Records from the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group for 2011

NOTES & RecoRDS NOTES & RecoRDS Gaffney, R.J. and Sleeman, D.P. (2007) Badger well as two tiny pieces of plastic measuring 6 Records from the Irish Whale and only 11 recorded, representing only 6.8 per cent Meles meles (L.) Track at Altitude in Co. Mayo. mm2 and 4 mm2 (S.Broszeit, pers. comm.). A Dolphin Group for 2011 of the total. Five species were recorded as live Irish Naturalists’ Journal 28: 344. small number of parasites were also found along stranding with, common dolphins having the Mullen, E.M., MacWhite, T., Maher, P.K., Kelly, the digestive tract. There was no evidence of very All records below have been submitted with highest number with eight individuals stranded D.J., Marples, N. and Good, M. (2013) recent feeding and no evidence that the animal adequate documentation and/or photographs to in six separate incidents. All other strandings were Foraging Eurasian badgers Meles meles and might have been foraging on salmon. put identification beyond doubt. The length is a of single animals including Harbour Porpoise (2), the presence of cattle in pastures. Do badgers Common dolphins are considered to be a linear measurement from the tip of the beak to Bottlenose Dolphin (1), Striped Dolphin (1) and avoid cattle? Applied Animal Behaviour Science. pelagic species, although they are occasionally the fork in the tail fin. Sperm Whale (1). 143: 130-137. sighted close to the coast. However, the The IWDG Stranding Scheme operates Neal, E. and Cheeseman, C. (1996) Badgers. T & movement so far up the River Lee is unusual throughout the year around the entire coastline Fin Whale AD Poyser Ltd, London. -

Natura Impact Statement Clew Bay Destination And

NATURA IMPACT STATEMENT IN SUPPORT OF THE APPROPRIATE ASSESSMENT FOR THE CLEW BAY DESTINATION AND EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT PLAN for: Fáilte Ireland 88-95 Amiens Street Dublin 1 by: CAAS Ltd. 1st Floor 24-26 Ormond Quay Upper Dublin 7 NOVEMBER 2020 Appropriate Assessment Natura Impact Statement for the Clew Bay Destination and Experience Development Plan Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Legislative Context ............................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Approach ...........................................................................................................................1 Section 2 Description of the Plan .................................................................................... 3 Section 3 Screening for Appropriate Assessment ........................................................... 5 3.1 Introduction to Screening ................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Identification of Relevant European sites .............................................................................. 5 3.3 Assessment Criteria and Screening ...................................................................................... 8 3.4 Other Plans and Programmes ........................................................................................... -

Survey Megalithic Tombs of Ireland

SURVEY OF THE MEGALITHIC TOMBS OF IRELAND Ruaidhri de Valera and Sean O Nuallain VOLUME II COUNTY MAYO DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE 1964 To be purchased from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, G.P.O. ARCADE, DUBLIN 1 or through any Bookseller SURVEY OF THE MEGALITHIC TOMBS OF IRELAND Ruaidhri de Valera and Sean O Nuallain VOLUME II COUNTY MAYO DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE 1964 To be purchased from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, G.P.O. ARCADE, DUBLIN 1 or through any Bookseller W PRINTED BY DUNDALGAITPRESS ( - TEMPEST) LTD., DUNDALK CONTENTS ALPHABETICAL INDEX TO DESCRIPTIONS, PLANS AND PHOTOGRAPHS OF TOMBS ........... v NUMERICAL LIST OF TOMBS ......... viii ALPHABETICAL INDEX TO SITES IN APPENDIX ...... vii INTRODUCTION ........... ix Previous Accounts of Co. Mayo Tombs ...... ix Scope and Plan of Present Volume ....... xiii Conventions Used in Plans ........ xv PART I. DESCRIPTIONS Descriptions of the Megalithic Tombs of Co. Mayo .... i Appendix: (a) Destroyed sites probably to be accepted as genuine Megalithic Tombs ......... 93 (b) Sites marked " Cromlech," etc., on O.S. Maps which are not accepted as Megalithic Tombs ..... 94 PART 2. DISCUSSION 1. MORPHOLOGY .......... 103 Court Cairns: Cairn and Revetment ....... 103 Courts .......... 104 Main Gallery ......... 106 Transepted Galleries and related forms .... 109 Orientation ......... no Portal Dolmens ......... no Wedge-shaped Gallery Graves: Main Chamber ........ in Portico .......... 112 Outer-walling . 112 Cairn .......... 112 Orientation ......... 113 2. DISTRIBUTION 113 Topography of Co. Mayo ....... 113 Court Cairns ......... 115 Portal Dolmens ......... 116 Wedge-shaped Gallery Graves . - . • 117 iii IV CONTENTS 3. THE PLACE OF THE MAYO TOMBS IN THE IRISH SERIES Court Cairns .....