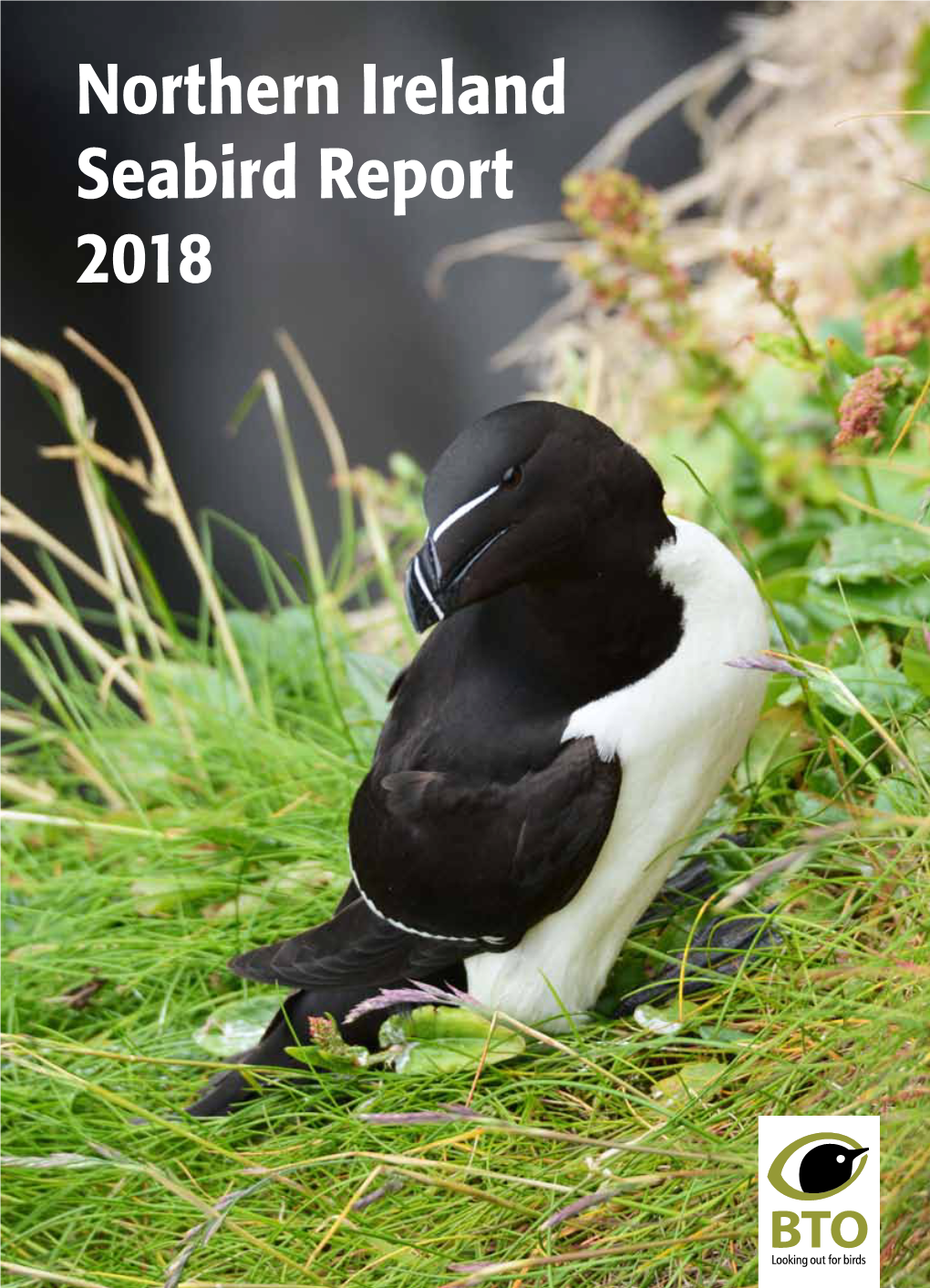

Northern Ireland Seabird Report 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, 19Ra AUGUST, 1966 MINISTRY of HOME AFFAIRS MINISTRY of HEALTH and SOCIAL SERVICES CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

304 THE BELFAST GAZETTE, 19ra AUGUST, 1966 ing to be the Nature Reserves Committee for a and Social Services, after consultation with the period of three years from 15th August, 1966: Ministry of Education, hereby appoints the following person to be a member of the Engineering Industry S. Boyd, Esq., J.P. Training Board. H. A. Burke, Esq., LL.B. W. A. Patterson, Esq., M.A., H.Dip.Ed., K. Cadman, Esq., B.Sc. Deputy Director of Education for the County R. W. Carlisle, Esq. Borough of Belfast. R. N. Crawford, Esq., B.Com.Sc., A.C.A. The term of office of the aforesaid member shall terminate on 30th September, 1967. J. Cunningham, Esq. Sealed with the Official Seal of the C. D. Deane, Esq., A.M.A. Ministry of Health and Social W. J. Eggeling, Esq., B.Sc., Ph.D., F.R.S.E. L.S. Services for Northern Ireland A. E. Henderson, Esq., B.Sc., Ph.D. this llth day of August, 1966. D. W. Leroux, Esq., B.Sc. W. G. H. Quigley, R. E. Parker, Esq., B.Sc. Assistant Secretary. J. Preston, Esq., B.Sc.(Tech.), B.Sc., Ph.D. He has further appointed the said R. N. Crawford, Esq., to be the Chairman of the Committee. Catering Industry Training Board The Ministry of Development has appointed Mr. In pursuance of the powers conferred on it by R. S. Rogers, O.B.E., to be Secretary to the Com- Section 1 of and Schedule 1 to the Industrial Train- mittee. ing Act (Northern Ireland) 1964, the Ministry of Health and Social Services hereby appoints the following person to be a member (representing em- ployers) of the Catering Industry Training Board, Notice is hereby given that the Ministry of Develop- that is to say: ment, in exercise of the powers vested in it by Section 18 of the Local Government Act (Northern H. -

Heritage Map Document

Route 1 Route 2 Route 3 1. Bishops Road 2. Londonderrry and 12. Beech Hill House 13. Loughs Agency 24. St Aengus’ Church 25. Grianán of Aileach bigfishdesign-ad.com Downhill, Co L’Derry Coleraine Railway Line 32 Ardmore Rd. BT47 3QP 22 Victoria Rd., Derry BT47 2AB Speenogue, Burt Carrowreagh, Burt Best viewed anywhere from Downhill to Magilligan begins. It took 200 men to build this road for the Earl In 1855 the railway between Coleraine and Beechill House was a major base for US marines Home to the cross-border agency with responsibility This beautiful church, dedicated to St. Aengus was This Early Iron Age stone fort at the summit of at this meeting of the waters that the river Foyle Foyle river the that waters the of meeting this at Bishop of Derry, Frederick Hervey in the late 1700s Londonderry was built which runs along the Atlantic during the Second World and now comprises a for the Foyle and Riverwatch which houses an designed by Liam Mc Cormick ( 1967) and has won Greenan, 808 ft above Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle, river Finn coming from Donegal in the west. It is is It west. the in Donegal from coming Finn river along the top of the 220m cliffs that overlook the and then the Foyle and gave rise to a wealth of museum to the period, an archive and a woodland aquarium that represents eights different habitats many awards. The shape of this circular church, is is one of the most impressive ancient monuments Magilligan Plain and Lough Foyle. -

The Development and Use of Ground-Based Rat Eradication Techniques in the UK

E.A. Bell Bell, E.A. It’s not all up in the air: the development and use of ground-based rat eradication techniques in the UK It’s not all up in the air: the development and use of ground-based rat eradication techniques in the UK E.A. Bell Wildlife Management International Ltd, P.O. Box 607, Blenheim 7201, New Zealand, <[email protected]>. Abstract Eradication techniques using ground-based devices were developed in New Zealand in the early 1970s to target invasive rodents. Since then, diff erent bait station designs, monitoring tools and rodenticide baits have been developed, and changes in fi eld techniques have improved and streamlined these operations. The use of these techniques has been taken around the world to eradicate rodents from islands. Eradication technology has moved rapidly from ground-based bait station operations to aerial application of rodenticides. However, regulations, presence of and attitudes of island- communities and presence of a variety of non-target species precludes the aerial application of rodenticides on islands in many countries. As such, ground-based operations are the only option available to many agencies for the eradication of invasive rodents from islands. It is important to recognise that the use of ground-based operations should be a valid option during the assessment phase of any eradication proposal even in countries that can legally apply bait from the air; in many instances the use of ground-based techniques can be as economic and rapid. The use of ground-based operations can also facilitate opportunities for in-depth monitoring of both target and non-target species. -

The Magheramorne Landslide, Northern Ireland Mechanics and Remedial Measures

Technical report ■The Magheramorne Landslide, Northern Ireland mechanics and remedial measures Richard J. CHANDLER Department of Civil Engineering, Imperial College of Science Technology and Medicine Key words: landslide case study; partial progressive failure; partial first-time failure ; factors of safety; movement observa- tions. 1. Introduction 2. The Magheramorne Landslide Case studies describing landslide investigations are a The Magheramorne landslide is located a few kilo- valuable resource. They provide information on the metres south of the town of Larne, on a coastal slope type and mechanics of the landslides of their geological running down to Larne Lough, a coastal inlet which area, and hence are a useful guide for studies of simi- opens to the Irish Sea; see Fig. 1. At the foot of the lar landslides in the same area or in similar geological slope are a major road (the "Coast Road") and a rail- conditions. Case studies dealing with remedial works way, both of which run on level ground about three to are also of interest, particularly where the effective- four metres above sea level. Away from Larne Lough, ness of the remedial works is reported. to the west, the slope steepens and rises to about 38 m This paper presents a landslide case study which de- above sea level (a.s.l.; Belfast datum) over a distance scribes the investigations and remedial works for a of 150 m, to the foot of a large man-made tip of rock landslide on the east coast of Northern Ireland, high- waste. This tip has side slopes inclined at about 35•‹, lighting those aspects of the study that are thought to and rises to about 100 m a.s.l. -

Consultation on the Designation of Inshore Marine Nature Reserves

Consultation on the designation of inshore Marine Nature Reserves Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture Rheynn Chymmltaght, Bee as Eirinys Consultation Paper June 2017 1 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Objectives of consultation 4 3. Background 5 4. Designation of current Conservation Zones as Marine Nature Reserves: 7 Little Ness 8 Langness 9 Calf of Man and Wart Bank 10 West Coast 11 5. Extension of protection of Fisheries Closed Areas and Fisheries Restricted Areas: 12 Port Erin 13 Douglas 14 Baie ny Carrickey 15 Niarbyl 17 Laxey 18 6. Proposed additional management measures for Ramsey Marine Nature Reserve 19 7. References 21 8. Feedback on consultation 23 9. Consultation response form 24 10. Appendix 1 – Features of Conservation Importance 29 11. Appendix 2 – List of consultees 31 2 1. Introduction “We have a natural and built environment which we conserve and cherish and which is adapted to cope with the threats from climate change.” Isle of Man Programme for Government, 2016-2021. The work of the Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture (DEFA) is guided by the core principles of environmental, economic and social sustainability. Seeking to apply these principles to the fisheries sector, the Department is progressing options for protecting the marine environment and supporting sustainable fisheries in the Isle of Man territorial sea. In the DEFA delivery plan for the Programme for Government 2016-2021 there is a commitment to increase the proportion of territorial seabed which is protected as marine nature reserve, from the current level of 3% to at least 6%. This target is aligned to the Programme for Government outcome “We have a diverse economy where people choose to work and invest” and the policy statement “Maximise the social and economic value of our territorial seabed.” The Isle of Man Government is a signatory to the OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Convention on Biological Diversity was extended to the Isle of Man in 2012. -

Binevenagh Binevenagh Make to Combine That Features Distinctive

National Trust acquired the property in 1976. in property the acquired Trust National Magilligan Point ©Tourism NI ©Tourism Point Magilligan rail journeys in the world”. the in journeys rail farmer, Isaac Hezlett, in 1761. His family lived there until the the until there lived family His 1761. in Hezlett, Isaac farmer, Londonderry and Coleraine as “one of the most beautiful beautiful most the of “one as Coleraine and Londonderry the rector of Dunboe and was taken over by a Presbyterian Presbyterian a by over taken was and Dunboe of rector the writer Michael Palin described the train journey between between journey train the described Palin Michael writer ‘crucks’. The cottage was probably built as a parsonage for for parsonage a as built probably was cottage The ‘crucks’. Ireland, measuring 610 and 280 metres respectively. Travel Travel respectively. metres 280 and 610 measuring Ireland, walls hide a fascinating early frame of curved timbers called called timbers curved of frame early fascinating a hide walls and Downhill – they are still the longest railway tunnels in in tunnels railway longest the still are they – Downhill and Ireland’s oldest surviving thatched cottage, its roughcast roughcast its cottage, thatched surviving oldest Ireland’s through two headlands on the route between Castlerock Castlerock between route the on headlands two through cottage dating from around 1691. Not only is it Northern Northern it is only Not 1691. around from dating cottage major engineering achievement, requiring tunnels to be cut cut be to tunnels requiring achievement, engineering major Hezlett House outside Castlerock, is a beautiful thatched thatched beautiful a is Castlerock, outside House Hezlett Company opened a line between these two towns. -

Single Jurisdiction in Northern Ireland

Single Jurisdiction in Northern Ireland. Background The Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service public consultation "Redrawing the Map: A Consultation on Court Boundaries in Northern Ireland” contained proposals to replace the current rigid statutory framework of court boundaries for County Courts and magistrates’ courts with a single jurisdiction within Northern Ireland underpinned by more flexible administrative arrangements. Stakeholders broadly welcomed the proposals. Single Jurisdiction reforms will be implemented on 31 October 2016. The legislation to give effect to the single jurisdiction is contained in Part 1 of the Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2015. Under the new arrangements, the jurisdiction of county courts and magistrates courts will no longer be determined by reference to County Court Divisions and Petty Sessions Districts. Instead these courts will exercise jurisdiction throughout Northern Ireland, similar to the way in which the Crown Court already operates. New Administrative Court Divisions The existing divisional structure will simultaneously be replaced with three new Administrative Court Divisions (ACDs). These Divisions will not define jurisdiction but rather will determine the area in which court business will ‘usually’ be heard. The three ACDs are:- North Eastern Division South Eastern Division Western Division. A map illustrating the geographical make-up of these Divisions has been attached at Annex A. Page 1 of 20 Although the legislation provides that different ACDs may be created for different types of court business (e.g. police or Public Prosecution Service boundaries for criminal business; Health Trust boundaries for family business) there will in the first instance be one single configuration of ACDs based on combinations of the eleven Local Government Districts for Northern Ireland. -

Cancer in Ireland 1994-2004: a Summary Report

Cancer in Ireland 1994-2004: A summary report A report of cancer incidence, mortality, treatment and survival in the North and South of Ireland: 1994-2004 Cliffs of Moher, Co. Clare, Ireland This report is accompanied by an extensive online version covering the top twenty cancer sites in Ireland. D.W. Donnelly, A.T. Gavin and H. Comber April 2009 This report should be cited as: Donnelly DW, Gavin AT and Comber H. Cancer in Ireland: A summary report. Northern Ireland Cancer Registry/National Cancer Registry, Ireland; 2009 NICR/NCRI Key findings INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY - Each year an average of 10,999 male and 10,510 female cancers* were diagnosed between 2000 and 2004 with 5,921 male and 5,340 female cancer deaths annually. - Rates† were lower in Northern Ireland by 10.0% for males, the difference a result of higher levels of prostate cancer in the Republic of Ireland. Female rates were 2.2% lower in Northern Ireland than the Republic of Ireland. - The most common male cancers were prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer and lymphoma, while among women they were breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer. - Incidence rates increased for males by 1.8% per year during 1999-2004 and for females by 0.8% per year during 1994-2004. The number of cases increased by an average of 255 male and 217 female cases per year. The largest increases were in prostate cancer, liver cancer and malignant melanoma. - Incidence rates were lower in Northern Ireland than in the Republic of Ireland for pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer and leukaemia among both sexes, for colorectal and prostate cancers among males and melanoma, breast cancer and cervical cancer among females. -

(HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children's Social Work

Northern Ireland Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children’s Social Work Belfast HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 028 90507000 Areas Greater Belfast area Further Contact Details Greater Belfast Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) 110 Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 6HD Website http://www.belfasttrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) South Eastern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001000300 Areas Lisburn, Dunmurry, Moira, Hillsborough, Bangor, Newtownards, Ards Peninsula, Comber, Downpatrick, Newcastle and Ballynahinch Further Contact Details Greater Lisburn Gateway North Down Gateway Team Down Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Team James Street Children’s Services Stewartstown Road Health Newtownards, BT23 4EP 81 Market Street Centre Tel: 028 91818518 Downpatrick, BT30 6LZ 212 Stewartstown Road Fax: 028 90564830 Tel: 028 44613511 Dunmurry Fax: 028 44615734 Belfast, BT17 0FG Tel: 028 90602705 Fax: 028 90629827 Website http://www.setrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) Northern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001234333 Areas Antrim, Carrickfergus, Newtownabbey, Larne, Ballymena, Cookstown, Magherafelt, Ballycastle, Ballymoney, Portrush and Coleraine Further Contact Details Central Gateway Team South Eastern Gateway Team Northern Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Unit 5A, Toome Business The Beeches Coleraine -

(2010) Records from the Irish Whale

INJ 31 (1) inside pages 10-12-10 proofs_Layout 1 10/12/2010 18:32 Page 50 Notes and Records Cetacean Notes species were reported with four sperm whales, two northern bottlenose whales, six Mesoplodon species, including a True’s beaked whale and two Records from the Irish Whale and pygmy sperm whales. This year saw the highest number of Sowerby’s beaked whales recorded Dolphin Group for 2009 stranded in a single year. Records of stranded pilot whales were down on previous years. Compilers: Mick O’Connell and Simon Berrow A total of 23 live stranding events was Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, recorded during this period, up from 17 in 2008 Merchants Quay, Kilrush, Co. Clare and closer to the 28 reported in 2007 by O’Connell and Berrow (2008). There were All records below have been submitted with however more individuals live stranded (53) adequate documentation and/or photographs to compared to previous years due to a two mass put identification beyond doubt. The length is a strandings involving pilot whales and bottlenose linear measurement from the tip of the beak to dolphins. Thirteen bottlenose dolphin strandings the fork in the tail fin. is a high number and it includes four live During 2009 we received 136 stranding stranding records. records (168 individuals) compared to 134 records (139 individuals) received in 2008 and Fin whale ( Balaenoptera physalus (L. 1758)) 144 records (149 individuals) in 2007. The Female. 19.7 m. Courtmacsherry, Co. Cork number of stranding records reported to the (W510429), 15 January 2009. Norman IWDG each year has reached somewhat of a Keane, Padraig Whooley, Courtmacsherry plateau (Fig. -

Commemorative Bench and Tree Programme

Terms & Conditions 1. Applications for the supply and installation of commemorative benches or trees will only be approved after a suitable available site has been agreed between Mid and East Antrim Borough Council and the named applicant. 2. Whilst the cost and installation of the bench or tree shall be the responsibility of the applicant, we agree to fund the maintenance of the bench or tree, unless it becomes, in our view, damaged beyond economic repair. If a bench or tree is in such a state of disrepair that it cannot be restored for safe use, we will remove the bench or tree and shall not be obliged to fund a replacement. 3. We accept no responsibility for the theft of any bench or tree save that we will report any incident or theft to the Police Service of Northern Ireland. 4. The bench or tree will be placed in a Mid and East Antrim Borough Council owned park, open space or cemetery. No other adornment (flowers, sculptures, etc.) will be allowed to be placed with the bench or tree. Any adornment will be promptly removed and disposed of by the Council. 5. We reserve the right to use our discretion to refuse any application. 6. All proposed inscriptions for commemorative plaques and any subsequent changes must be approved by us. The wording of inscriptions is subject to our legal obligations with regards to the promotion of equality and good relations. Any inscription containing wording which we deem to be offensive or inappropriate will not be considered for approval. Commemorative Bench and Tree Programme Parks & Open Spaces Service -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic.