Download Whole Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Traffic Recognition in Cellular Networks

IT 09 010 Examensarbete 30 hp March 2009 Traffic Recognition in Cellular Networks Alexandros Tsourtis Institutionen för informationsteknologi Department of Information Technology Abstract Traffic Recognition in Cellular Networks Alexandros Tsourtis Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Traffic recognition is a powerful tool that could provide valuable information about the network to the network operator. The association of additional information Besöksadress: carried by control packets in the core cellular network would help identify the traffic Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 that stem from each user and acquire statistics about the usage of the network Hus 4, Plan 0 resources and aid detecting problems that only one or a small group of users experience. The program used is called TAM and it operates only on Internet traffic. Postadress: The enhancements of the program included the support for the Gn and Gi interfaces Box 536 751 21 Uppsala of the cellular network where the control traffic is transferred via the GTP and RADIUS protocols respectively. Furthermore, the program output is verified using Telefon: two other tools that operate on the field with satisfactory results and weaknesses 018 – 471 30 03 were detected on all tools studied. Finally, the results of TAM were demonstrated Telefax: with conclusions being drawn about the statistics of the network. The thesis 018 – 471 30 00 concludes with suggestions for improving the program in the future. Hemsida: http://www.teknat.uu.se/student Handledare: Tord Westholm Ämnesgranskare: Ivan Christoff Examinator: Anders Jansson IT 09 010 Tryckt av: Reprocentralen ITC Acknowledgements My thanks goes first to my supervisor in Ericsson, Tord Westholm for sug- gesting valuable comments, helping to structure the work and the presenta- tion and allowing me to take decisions concerning the project direction. -

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian A summary of the main discussion points generated at a two-day conference organized by the Smithsonian Music group, a pan- Institutional committee, with the support of Grand Challenges Consortia Level One funding June 2012 Produced by the Office of Policy and Analysis (OP&A) Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Conference Participants ..................................................................................................................... 5 Report Structure and Other Conference Records ............................................................................ 7 Key Takeaway ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Smithsonian Music: Locus of Leadership and an Integrated Approach .............................. 8 Conference Proceedings ...................................................................................................................... 10 Remarks from SI Leadership ........................................................................................................ -

The Application Usage and Risk Report an Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise

The Application Usage and Risk Report An Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise 8th Edition, December 2011 Palo Alto Networks 3300 Olcott Street Santa Clara, CA 94089 www.paloaltonetworks.com Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Demographics ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Social Networking Use Becomes More Active ................................................................ 5 Facebook Applications Bandwidth Consumption Triples .......................................................................... 5 Twitter Bandwidth Consumption Increases 7-Fold ................................................................................... 6 Some Perspective On Bandwidth Consumption .................................................................................... 7 Managing the Risks .................................................................................................................................... 7 Browser-based Filesharing: Work vs. Entertainment .................................................... 8 Infrastructure- or Productivity-Oriented Browser-based Filesharing ..................................................... 9 Entertainment Oriented Browser-based Filesharing .............................................................................. 10 Comparing Frequency and Volume of Use -

Fair Use As Cultural Appropriation

Fair Use as Cultural Appropriation Trevor G. Reed* Over the last four decades, scholars from diverse disciplines have documented a wide variety of cultural appropriations from Indigenous peoples and the harms these have inflicted. Copyright law provides at least some protection against appropriations of Indigenous culture— particularly for copyrightable songs, dances, oral histories, and other forms of Indigenous cultural creativity. But it is admittedly an imperfect fit for combatting cultural appropriation, allowing some publicly beneficial uses of protected works without the consent of the copyright owner under certain exceptions, foremost being copyright’s fair use doctrine. This Article evaluates fair use as a gatekeeping mechanism for unauthorized uses of copyrighted culture, one which empowers courts to sanction or disapprove of cultural appropriations to further copyright’s goal of promoting creative production. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38V97ZS35. Copyright © 2021 Trevor G. Reed * Trevor Reed (Hopi) is an Associate Professor of Law at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. The author thanks June Besek, Bruce Boyden, Christine Haight Farley, Eric Goldman, Rhett Larson, Jake Linford, Jon Kappes, Kali Murray, Guy Rub, Troy Rule, Erin Scharff, Joshua Sellers, Michael Selmi, Justin Weinstein-Tull, and Andrew Woods for their helpful feedback on this project. The author also thanks Qiaoqui (Jo) Li, Elizabeth Murphy, Jillian Bauman, M. Vincent Amato and Isaac Kort-Meade for their research assistance. Early versions of this paper were presented at, and received helpful feedback from, the 2019 Race + IP conference, faculty colloquia at the University of Arizona and University of Washington, the American Association for Law School’s annual meeting, and the American Library Association’s CopyTalk series. -

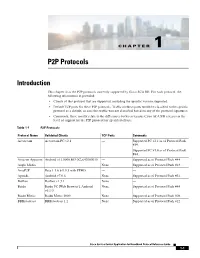

P2P Protocols

CHAPTER 1 P2P Protocols Introduction This chapter lists the P2P protocols currently supported by Cisco SCA BB. For each protocol, the following information is provided: • Clients of this protocol that are supported, including the specific version supported. • Default TCP ports for these P2P protocols. Traffic on these ports would be classified to the specific protocol as a default, in case this traffic was not classified based on any of the protocol signatures. • Comments; these mostly relate to the differences between various Cisco SCA BB releases in the level of support for the P2P protocol for specified clients. Table 1-1 P2P Protocols Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments Acestream Acestream PC v2.1 — Supported PC v2.1 as of Protocol Pack #39. Supported PC v3.0 as of Protocol Pack #44. Amazon Appstore Android v12.0000.803.0C_642000010 — Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. Angle Media — None Supported as of Protocol Pack #13. AntsP2P Beta 1.5.6 b 0.9.3 with PP#05 — — Aptoide Android v7.0.6 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #52. BaiBao BaiBao v1.3.1 None — Baidu Baidu PC [Web Browser], Android None Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. v6.1.0 Baidu Movie Baidu Movie 2000 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #08. BBBroadcast BBBroadcast 1.2 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #12. Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide 1-1 Chapter 1 P2P Protocols Introduction Table 1-1 P2P Protocols (continued) Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments BitTorrent BitTorrent v4.0.1 6881-6889, 6969 Supported Bittorrent Sync as of PP#38 Android v-1.1.37, iOS v-1.1.118 ans PC exeem v0.23 v-1.1.27. -

Swierstra's Francolin Francolinus Swierstrai

abcbul 28-070718.qxp 7/18/2007 2:05 PM Page 175 Swierstra’s Francolin Francolinus swierstrai: a bibliography and summary of specimens Michael S. L. Mills Le Francolin de Swierstra Francolinus swierstrai: bibliographie et catalogue des spécimens. Le Francolin de Swierstra Francolinus swierstrai, endémique aux montagnes de l’Angola occidental, est considérée comme une espèce menacée (avec le statut de ‘Vulnérable’). En l’absence d’obser- vations entre 1971 et 2005, nous connaissons très peu de choses sur cette espèce. Cette note résume l’information disponible, basée sur 19 spécimens récoltés de 1907 à 1971, et présente une bibliographie complète, dans l’espoir d’encourager plus de recherches sur l’espèce. Summary. Swierstra’s Francolin Francolinus swierstrai is the only threatened bird endemic to the montane region of Western Angola. With no sightings between 1971 and August 2005, knowl- edge of this species is very poor. This note presents a summary of available information, based on 19 specimens collected between 1907 and 1971, and provides a complete bibliography, in order to encourage further work on this high-priority species. wierstra’s Francolin Francolinus swierstrai (or SSwierstra’s Spurfowl Pternistis swierstrai) was last recorded in February 1971 (Pinto 1983), until its rediscovery at Mt Moco in August 2005 (Mills & Dean in prep.). This Vulnerable species (BirdLife International 2000, 2004) is the only threatened bird endemic to montane western Angola, an area of critical importance for biodiver- sity conservation (Bibby et al. 1992, Stattersfield et al. 1998). Swierstra’s Francolin has a highly fragmented range of c.18,500 km2 and is suspected, despite the complete lack of sightings for more than 30 years, to have a declining population estimated at 2,500–9,999. -

Soulseek Free Download Windows 10 Soulseek 157 NS 13E

soulseek free download windows 10 Soulseek 157 NS 13e. Soulseek is an ad-free, spyware free, and just plain free file sharing (P2P) application. Addition to basic file sharing application, it has a community and community-related features. Based on peer-to-peer technology, virtual rooms allow you to meet people with the same interests, share information, and chat freely using real-time messages in public or private. Screenshots: Other editions: HTML code for linking to this page: Keywords: soulseek p2p file sharing peer-to-peer community chat chat. 1 License and operating system information is based on latest version of the software. SoulSeek. Soulseek is a p2p program that was born in order to share music, intending to be a platform to help new artists find a place in the music industry, or at least, to let them be listened to by Soulseek users. Soulseek grew and now it is used for sharing all kind of files, but specifically music. SoulSeek is the competitor of other p2p programs like eMule or Kazaa. One point on its favor is that it is Ad-free, spyware free, totally free, and in addition, you don't have to register to go into their net. Soulseek, with its built-in people matching system, is a great way to make new friends and expand your mind! SoulSeek. SoulSeek es una aplicación P2P para compartir archivos a través de Internet, cuyo contenido ha sido orientado a la música. El propósito de SoulSeek es mejorar la velocidad de descarga con respecto a susmás direcctos competidores, como eMule o Kazaa. -

Instructions for Using Your PC ǍʻĒˊ Ƽ͔ūś

Instructions for using your PC ǍʻĒˊ ƽ͔ūś Be careful with computer viruses !!! Be careful of sending ᡅĽ/ͼ͛ᩥਜ਼ƶ҉ɦϹ࿕ZPǎ Ǖễƅ͟¦ᰈ Make sure to install anti-virus software in your PC personal profile and ᡅƽញƼɦḳâ 5☦ՈǍʻPǎᡅ !!! information !!! It is very dangerous !!! ΚTẝ«ŵ┭ՈT Stop violation of copyright concerning illegal acts of ơųጛňƿՈ☢ͩ ⚷<ǕOᜐ&« transmitting music and ₑᡅՈϔǒ]ᡅ others through the Don’t forget to backup ඡȭ]dzÑՈ Internet !!! important data !!! Ȥᩴ̣é If another person looks in at your E-mail, it’s a big ὲâΞȘᝯɣr problem !!! Don’t install software in dz]ǣrPǎᡅ ]ᡅîPéḳâ╓ ͛ƽញ4̶ᾬϹ࿕ ۅTake care of keeping your some other PCs without ˊΙǺ password !!! permission !!! ₐ Stop sending the followings !!! ŌՈϹوInformation against public order and Somebody targets on your PC for Pǎ]ᡅǕễạǑ͘͝ࢭÛ ΞȘƅ¦Ƿń morals illegal access !!! Ոƅ͟ǻᢊ᫁ĐՈ ࿕Ϭ⓶̗ʵ£࿁îƷljĈ Information about discrimination, Shut out those attacks with firewall untruth and bad reputation against a !!! Ǎʻ ᰻ǡT person ᤘἌ᭔ ᆘჍഀ ጠᅼૐᾑ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞęɪᬡᬡǰɟ ᆘȐೈ ᾑ ጠᅼ3ظ ᤘἌ᭔ ǰɟᯓۀ᭞ᮞᮐᮧ᭪᭑ᮖ᭤ᬞᬢ ഄᅤ Έʡȩîᬡ͒ͮᬢـ ᅼܘᆘȐೈ ǸᆜሹظᤘἌ᭔ ཬᴔ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞᬢŽᬍ᭑ᮖ᭤̛ɏ᭨ᮀ᭳ᭅ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘Π ؼ˨ഀ ୈὼ$ ഄጵ↬3L ʍ୰ᬞᯓ ᄨῼ33 Ȋථᬚᬌᬻᯓ ഄ˽ ઁǢᬝຨϙଙͮـᅰჴڹެ ሤᆵͨ˜Ɍ ጵႸᾀ żᆘ᭔ ᬝᬜΪ̎UઁɃᬢ ࡶ୰ᬝ᭲ᮧ᭪ᬢ ᄨؼᾭᄨ ᾑ ٕᅨ ΰ̛ᬞ᭫ᮌᯓ ᭻᭮᭚᭮ᮂᭅ ሬČ ཬȴ3 ᾘɤɟ3 Ƌᬿᬍᬞᯓ ᬿᬒᬼۏąഄᅼ Ѹᆠᅨ ᮌᮧᮖᭅ ᛴܠ ఼ ᆬð3 ᤘἌ᭔ ƂŬᯓ ᭨ᮀ᭳᭑᭒ᭅƖ̳ᬞ ĩᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞٴ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘ ᭼᭤ᮚᮧ᭴ᬡɼǂᬢ ڹެ ᵌೈჰ˨ ˜ϐ ᛄሤ↬3 ᆜೈᯌ ϤᏤ ᬊᬖᬽᬊᬻᯓ ᮞ᭤᭳ᮧᮖᬊᬝᬚ ሬČʀ ͌ǜ ąഄᅼ ΰ̛ᬞ ޅᬝᬒᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᭅ ᤘἌ᭔Π ͬϐʼ ᆬð3 ʏͦᬞɃᬌᬾȩî ēᬖᬙᬾᯓ ܘˑˑᏬୀΠ ᄨؼὼ ሹ ߍɋᬞᬒᬾȩî ᮀᭌ᭑᭔ᮧᮖwƫᬚފᴰᆘ࿘ჸ $±ᅠʀ =Ė ܘČٍᅨ ᙌۨ5ࡨٍὼ ሹ ഄϤᏤ ᤘἌ᭔ ኩ˰Π3 ᬢ͒ͮᬊᬝᯓ ᭢ᮎ᭮᭳᭑᭳ᬊᬻᯓـ ʧʧ¥¥ᬚᬚP2PP2P᭨᭨ᮀᮀ᭳᭳᭑᭑᭒᭒ᬢᬢ DODO NOTNOT useuse P2PP2P softwaresoftware ̦̦ɪɪᬚᬚᬀᬀᬱᬱᬎᬎᭆᭆᯓᯓ inin campuscampus networknetwork !!!! Z ʧ¥᭸᭮᭳ᮚᮧ᭚ᬞᬄᬾͮᬢȴƏΜˉ᭢᭤᭱ Z All communications in our campus network are ᬈᬿᬙᬱᬌʧ¥ᬚP2P᭨ᮀ always monitored automatically. -

The Music Hunter's Quarry from a Trotting Horse

Career (Doubleday, 1969), provides an apt description of her profession, since from 1929 to 1979 she was truly a hunter The Music Hunter's Quarry from a of music. She was among those who were Trotting Horse ethnomusicologists long before that word came into use. Exposure to the tapes in the Boulton collection causes one Rick Torgerson to realize that Laura Boulton had seen a number of cultures before they became permanently changed by the technology of the modern world. In 1991 the Laura Boulton Foundation awarded a Because I am a cataloger and not a researcher, I do grant to the Archives of Traditional Music for the purpose not have the luxury of exploring each collection in depth. of hiring a librarian to catalog the sound recordings from Rather, I have the pleasure of surveying the entire the Boulton Collection. The cataloging was to appear in the collection "from a trotting horse." I examine a collection national online union catalog of the Online Computer long enough to be able to describe and summarize what is Library Center, Inc. (OCLC), as well as in Indiana there, and then I must move on to the next collection. University's online catalog, 10. I began work on the Boulton Just as the radio provides the listener the freedom to Collection as cataloger in February of 1992. imagine what is being described, the Laura Boulton tapes The Laura Boulton Collection has been distributed have provided with me with dozens of imaginary voyages among the following institutions: Columbia University, the through time and space, allowing me to witness in part Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution, and the those events, people, and scenes that have gone by and will Mathers Museum of World Cultures and the Archives of never be again. -

Balancing Your Internet Cyber-Life with Privacy and Security

. Balancing Your Internet Cyber-Life with Privacy and Security Joseph Guarino Owner/Sr. Consultant Evolutionary IT CISSP, LPIC, MCSE 2000, MCSE 2003, PMP www.evolutionaryit.com in association with GBC/ACM Often... When I speak about security/privacy threats to non-technical customers, friends and family are incredulous. It's almost as if I am speaking about science fiction. Copyright © Evolutionary IT 2008 2 Security is a real concern unlike Bigfoot. Frame from Patterson-Gimlin film taken on October 21st, 1967 Copyright © Evolutionary IT 2008 3 Objectives ● Elucidate and demystify the subjects of cyber security and privacy in plain English. ● Explain why your privacy/security is important and how to protect it. ● Impart understanding of the privacy/security risks, impacts, ramifications. ● Give you practical knowledge to protect yourself, family and community. Copyright © Evolutionary IT 2008 4 Who am I? Joseph Guarino Working in IT for last 15 years: Systems, Network, Security Admin, Technical Marketing, Project Management, IT Management CEO/Sr. IT consultant with my own firm Evolutionary IT CISSP, LPIC, MCSE, PMP www.evolutionaryit.com Computer Security The fundamentals for the everyday users. Copyright © Evolutionary IT 2008 6 Common Misperceptions ● “I have anti-virus software...” ● “I don't personally have anything of value on my computer...” ● “I have a firewall...” ● “There are no major financial risks...” Copyright © Evolutionary IT 2008 7 Key terms/concepts Define some key terms... Copyright © Evolutionary IT 2008 8 General Terms ● Software Bug – an error, flaw or mistake in a computer program. ● Vulnerability – is a weakness in a system that allows an attacker to exploit or otherwise violate the integrity of your system.