Mutual Savings Banks and Building and Loan Associations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation of Savings-Bank Life Insurance in Massachusetts and New York

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Frances Perkins, Secretary BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS Isador Lubin, Commissioner (on leave) A . F. Hinrichs, Acting Commissioner + Operation of Savings-Bank Life Insurance in Massachusetts and New York Revision of Bulletin No. 615: The Massachusetts System of Savings-Bank Life Insurance, by Edward Berman ♦ Bulletin 7s[o. 688 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR F rances P er k ins, S e c r e t a r y + BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS I s a d o r L tjbin, Commissioner (o n lea v e) A. F. H in r ic h s , Acting Commissioner Donald Davenport, Chief, Employ Aryness Joy, Chief, Prices and Cost of ment and Occupational Outlook Living Branch Branch N. Arnold Tolies, Chief, Working Con Henry J. Fitzgerald, Chief, Business ditions and Industrial Relations Management Branch Branch Hugh S. Hanna, Chief, Editorial and Research Sidney W. Wilcox, Chief Statistician CHIEFS OF DIVISIONS Herman B. Byer, Construction and Charles F. Sharkey, Labor Law In Public Employment formation J. M. Cutts, Wholesale Prices Boris Stern, Labor Information Ser W. Duane Evans, Productivity and vice Technological Developments Stella Stewart, Retail Prices Swen Kjaer, Industrial Accidents John J. Mahanev, Machine Tabula Lewis E. Talbert, Employment Sta tion tistics Robert J. Myers, Wage and Hour Emmett H. Welch, Occupational Out Statistics look Florence Peterson, Industrial Rela tions Faith M. Williams, Cost of Living i i Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. -

Sound Banking

Sound Banking Sound Banking Rebecca Söderström Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Auditorium Minus, Gustavianum, Akademigatan 3, Uppsala, Friday, 12 May 2017 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Laws. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Nina Dietz Legind. Abstract Söderström, R. 2017. Sound Banking. 370 pp. Uppsala: Juridiska fakulteten, Uppsala universitet. ISBN 978-91-506-2627-8. Banks are subject to a comprehensive body of legal rules and conduct their business under constant supervision of authorities. Since the financial crisis of 2008, the number of rules governing banking has grown and the structures of supervision have likewise been enhanced. This thesis analyses various aspects of the regulation and supervision of banks, and focuses especially on soundness as a normative concept to regulate banks. Soundness is a legal prerequisite in, for example Swedish, law and appears in relation to banking in many other jurisdictions. The aims of this thesis are to examine how the normative concept of soundness functions in the regulation and supervision of banks, to present general insights into how banking regulation and supervision function and how the financial crisis of 2008 has affected banking regulation and supervision. The thesis proposes a taxonomy of soundness – confidence – stability to describe the normative context of soundness. The taxonomy is connected to the theoretical arguments for bank regulation and is used as a tool to analyse three areas of banking regulation: authorisation, capital requirements and banks in trauma. The three areas correspond to the outline of the thesis according to The Story of the Bank, which includes the formation, operation and failure of banks. -

2581, Effective January 12, 1984

In The Matter of the Petition of "M" Bank, A Mutual Savings Bank and the "O" Bank for a Declaratory Ruling DOC #2581, Effective January 12, 1984 Pursuant to RSA 541-A:1, IV, RSA 541-A:2, I (d) and Rev 104.04, New Hampshire Code of Administrative Rules the "M" Bank, a Mutual Savings Bank (hereinafter referred to as "Bank") and "O" Bank (hereinafter referred to as "Holding Company") a business corporation organized and existing pursuant to RSA 293-A with its principal place of business in .............., N. H., petition the Department of Revenue Administration for a declaratory ruling with respect to the New Hampshire tax consequences of the conversion of the "M" Bank, a Mutual Savings Bank, from mutual to stock form, as a subsidiary of "O" Bank of ..............., New Hampshire. Through its attorneys-in-fact, the Petitioners represent the following: The purpose of the Plan of Conversion is to accomplish (a) the conversion of a mutual savings bank to a "guaranty" (stock) savings bank subsidiary of Holding Company, and (b) the sale of stock of Holding Company to Bank depositors and other classes of potential subscribers, by a procedure similar to that established by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board ("FHLBB") for conversions of federally chartered mutual thrift institutions to stock forms. Pursuant to New Hampshire RSA 386:10 (II), these procedures and regulations have also been adopted by the New Hampshire General Court (Legislature) and Banking Commissioner for use with respect to conversion of state-chartered mutual savings banks to stock banks. On September 14, 1983 the Board of Directors of Bank adopted a Plan of Conversion (hereinafter referred to as "Plan") whereby Bank will be converted to a guaranty (stock) savings bank (hereinafter sometimes referred to as "Stock Bank" to distinguish the same from the Bank prior to conversion) all of the stock of which will be held by Holding Company. -

Insurance Times: MASS. BANKS TRIED HOLDING COMPANY ROUTE BEFORE INSURER LIBERTY MUTUAL December 11, 2001, Vol. XX No. 25 Giant

Insurance Times: MASS. BANKS TRIED HOLDING COMPANY ROUTE BEFORE INSURER LIBERTY MUTUAL December 11, 2001, Vol. XX No. 25 Giant P/C Insurer Wins Approval to Form MHC by Mark Hollmer InsuranceTimes BOSTON — Eastern Bank was once a small mutual savings bank based in Lynn. But then in 1989, the Massachusetts Division of Banks approved the bank’s application to reorganize as a mutual holding company – the first in the state to do so. Andrew Calamare was Massachusetts Commissioner of Banks at the time. He said the change helped Eastern to become a regional powerhouse. “It has certainly not hurt them,” said Calamare, now president and CEO of the Life Insurance Association of Massachusetts. “Now it is the second largest bank in the … state chartered system,” he said. Liberty Mutual Status Twelve years later, Liberty Mutual has become the state’s first property casualty insurer to win mutual holding company status. Insurance Commissioner Linda Ruthardt approved Liberty Mutual’s mutual holding company application at the end of November, the first mutual insurer to do so under a 1998 state law. The approval allows Liberty mutual to form a holding company that becomes the corporate parent of Liberty Mutual Insurance Co. and sister divisions Liberty Mutual Fire and Liberty Mutual Life. DOI approval to merger Liberty subsidiary Wausau Insurance into the mutual holding company and also reorganize Liberty Mutual Fire within the new system is still pending, however. When all is complete, Liberty Mutual will maintain mutuality but gain the right to offer stock if it chooses. Shareholders can own up to 49 percent of the company, but policyholders will always own at least 51 percent. -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 211/Friday, October 31, 2014/Notices

64784 Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 211 / Friday, October 31, 2014 / Notices FEDERAL HOUSING FINANCE fhfa.gov or 202–658–9266, Office of certified as community development AGENCY Housing and Regulatory Policy, Division financial institutions (CDFIs) are of Housing Mission and Goals, Federal deemed to be in compliance with the [No. 2014–N–13] Housing Finance Agency, Ninth Floor, community support requirements and Federal Home Loan Bank Members 400 Seventh Street SW., Washington, are not subject to periodic community Selected for Community Support DC 20024. support review, unless the CDFI Review 2014–2015 Review Cycle—4th SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: member is also an insured depository institution or a CDFI credit union. 12 Round I. Selection for Community Support CFR 1290.2(e). AGENCY: Federal Housing Finance Review Under the regulation, FHFA selects Agency. Section 10(g)(1) of the Federal Home approximately one-eighth of the ACTION: Notice. Loan Bank Act (Bank Act) requires members in each Bank district for FHFA to promulgate regulations community support review each SUMMARY: The Federal Housing Finance establishing standards of community calendar quarter. 12 CFR 1290.2(a). Agency (FHFA) is announcing the investment or service that Bank FHFA will not review an institution’s Federal Home Loan Bank (Bank) members must meet in order to community support performance until it members it has selected for the 2014– maintain access to long-term Bank has been a Bank member for at least one 2015 Review Cycle—4th Round under advances. See 12 U.S.C. 1430(g)(1). The year. Selection for review is not, nor FHFA’s community support regulations promulgated by FHFA must should it be construed as, any requirements regulation. -

Disclosure 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Social Responsibility Vision MAPFRE wants to be the most trusted global insurance company Mission We are a multinational team that continuously strives to improve our service and develop the best relationship possible with our customers, distributors, suppliers, shareholders and Society Values SOLVENCY INTEGRITY SERVICE VOCATION INNOVATIVE LEADERSHIP COMMITTED TEAM Values SOLVENCY Financial strength with sustainable results. International diversification and consolidation in various markets. INTEGRITY Ethics govern the behaviour of all personnel. Socially responsible focus in all of our activities. SERVICE VOCATION Constant search for excellence in the development of our activities. Continuous initiatives focused on minding our relationship with our customers. INNOVATIVE LEADERSHIP Willingness to surpass ourselves and to constantly improve. Useful technology for servicing the businesses and their objectives. COMMITTED TEAM Total team commitment with MAPFRE’s project. Constant training and development of the team’s capabilities and skills. ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Social Responsibility Table of contents 2 1. Chairman’s Letter 4 4. MAPFRE’s social dimension 26 2. General Information 6 MAPFRE and its employees 27 MAPFRE and its customers 38 Presence 8 MAPFRE and its shareholders 55 MAPFRE Group’s corporate organization chart 9 MAPFRE and the professionals and entities Key economic figures 10 that help distribute products 57 Governing Bodies 11 MAPFRE and its suppliers 62 3. MAPFRE and Corporate Social 5. MAPFRE’s environmental -

Edited Excerpt on Mutual Form from Howell E. Jackson & Edward L

§ 5. The Mutual Form -1- Edited Excerpt on Mutual Form from Howell E. Jackson & Edward L. Symonds, Jr., Regulation of Financial Institutions 551-78 (West 1999) Section 5. The Mutual Form We now turn our attention from the primary focus of insurance regulation -- the relationship between insurer and insured -- to issues of organizational form. One peculiarity of the insurance industry is that many major firms are organized as "mutuals" -- that is legal entities that lack traditional equity shareholders. For example, in the life insurance industry as of 1994, mutual insurance companies held forty-one percent of industry assets. Moreover, six of the ten largest life insurance companies were organized in mutual form. On the property-casualty side, mutuals are somewhat less significant (holding more than a quarter of sector assets), but still constituted a substantial segment of the industry. The focus of attention in this section of the casebook is the "demutualization process," which consists of the legal arrangements whereby mutuals change their corporate form, either through liquidation or conversion into more traditional stock corporations. Demutualization is not unique to insurance companies, and has applications to other types of financial intermediaries, most notably savings and loan associations and savings banks, which also often organize themselves in mutual form. While this section is primarily concerned with the demutualization of insurance companies, we also consider briefly a parallel development in the savings bank industry. A. Demutualization of Insurance Companies To understand the demutualization process, one must first have a general appreciation of the legal relationship between mutual insurance companies and their policyholders. -

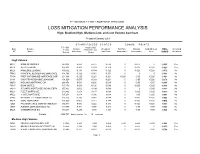

LOSS MITIGATION PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS High, Medium-High, Medium-Low, and Low Volume Servicers

FY 2000 SINGLE FAMILY MORTGAGE SERVICING LOSS MITIGATION PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS High, Medium-High, Medium-Low, and Low Volume Servicers Prepared January 2001 S T A N D A R D I Z E D S C O R E S B O N U S P O I N T S FY 1999 Actual Loss/ Svcr Servicer Loans Default Potential Loss Weighted FirstTime Minority UnderServed FINAL Increased ID * Name Scored Rate Score Score Total Score Homeowner Homeowner Area SCORE Incentives High Volume MUL1 BANK OF AMERICA 240,318 0.059 -0.727 -0.530 0 -0.025 0 -0.555 Yes MUL6 WELLS FARGO 656,303 -0.005 -0.503 -0.379 0 -0.025 -0.025 -0.429 Yes MUL5 HOMESIDE LENDING 439,502 -0.136 -0.384 -0.322 0 -0.025 -0.025 -0.372 No 75640 PRINCIPAL RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE 191,398 -0.122 -0.361 -0.301 0 0 0 -0.301 No 77396 FIRST NATIONWIDE MORTGAGE COR 211,449 -0.125 -0.227 -0.201 -0.025 -0.05 -0.025 -0.301 No 64141 COUNTRYWIDE HOME LOANS INC 491,029 -0.075 -0.243 -0.201 0 -0.05 -0.025 -0.276 No 39276 MIDLAND MORTGAGE CO 266,458 0.521 -0.286 -0.085 0 -0.05 -0.05 -0.185 No 73815 BANK UNITED 117,179 0.039 -0.120 -0.080 0 -0.025 -0.025 -0.130 No 68013 ATLANTIC MORTGAGE AND INVESTM 155,832 -0.032 -0.104 -0.086 0 0 -0.025 -0.111 No MUL3 FLEET MORTGAGE 319,862 -0.258 0.137 0.038 0 -0.025 -0.025 -0.012 No MUL2 CHASE MORTGAGE 597,276 -0.018 0.096 0.068 0 -0.05 -0.025 -0.007 No 38092 NATIONAL CITY MORTGAGE CO 105,256 -0.236 0.142 0.048 0 -0.025 -0.025 -0.002 No MUL4 GMAC MORTGAGE 136,099 -0.057 0.211 0.144 0 -0.025 -0.025 0.094 No 12621 PNC MORTGAGE CORP OF AMERICA 102,937 0.082 0.222 0.187 0 -0.025 -0.025 0.137 No 10757 AURORA LOAN -

Conversion of Credit Union Charter to Mutual Savings Bank Charter: Current Legal Process and Congressional Response Name Redacted Legislative Attorney

Conversion of Credit Union Charter to Mutual Savings Bank Charter: Current Legal Process and Congressional Response name redacted Legislative Attorney December 21, 2006 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RS22364 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Conversion of Credit Union Charter to Mutual Savings Bank Charter Summary There are several statutory requirements imposed by the Credit Union Membership Access Act (CUMAA) for converting a federal credit union to a mutual savings bank. In addition, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), the federal agency that charters and supervises federal credit unions, has issued regulations requiring significant disclosures by a federal credit union attempting to convert its charter to a mutual savings bank. Some of these disclosures are considered by critics to be speculative in nature, such as whether the directors of the converted institution intend later to convert to a stock-issuing entity, thereby possibly enriching themselves. Others believe that this kind of information is at the heart of the conversion process and should be disclosed. H.R. 3206, 109th Congress, was introduced to limit the kinds of disclosures required, in particular disclosures of a speculative nature. On May 11, 2006, the House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit held hearings on the bill. On December 14, 2006, the NCUA approved final rules governing conversions of credit unions to mutual savings banks or mutual savings associations. This report will be updated as needed. Congressional Research Service Conversion of Credit Union Charter to Mutual Savings Bank Charter ection 202 of the Credit Union Membership Access Act (CUMAA)1 amended the provision of the Federal Credit Union Act2 concerning conversion3 of insured federal credit unions4 to S mutual savings banks.5 This 1998 amendment added subsection (b)(2) to 12 U.S.C. -

2018 DFS Annual Report

ANDREW M. CUOMO LINDA A. LACEWELL Governor Superintendent June 15, 2019 To the Governor and Legislature: As Acting Superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services, I am pleased to submit the 2018 Annual Report as required by Article 2, Section 207 of the Financial Services Law. Throughout 2018, the Department carried out its mission to protect consumers and to promote the development of sound, fair financial services. The Department’s varied work is detailed in the report. As its charter instructs, the Department continues to work aggressively to foster the growth of a fair, robust financial services industry and to protect consumers. I hope you find the report useful. Respectfully submitted, Linda A. Lacewell Acting Superintendent 2018 Annual Report Linda A. Lacewell, Superintendent INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 MAJOR ACCOMPLISHMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 3 INSURANCE DIVISION OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................. 14 BANKING DIVISION OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................................... 16 REAL ESTATE FINANCE DIVISION OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................ -

Mutual Institutions: Owned by the Communities They Serve

MUTUAL INSTITUTIONS: OWNED BY THE COMMUNITIES THEY SERVE Introduction Mutual savings banks and mutual savings and loan associations (S&Ls) form a unique part of the banking industry, in that they are owned by their depositors rather than by share- holders.1 An institution can be mutually owned at the level of the banking charter or at the level of the holding company, in structures known as mutual holding companies (MHCs). In the latter case, depositors own the holding company, which in turn owns a majority of the stock issued by a subsidiary bank.2 Unlike stock institutions that may increase equity capital by issuing new shares, mutual institutions generally augment their net worth through retained earnings. While reliance on retained earnings provides for a steady source of capital for profitable institutions, it also fosters conservative lending, as a mutual cannot raise equity capital externally through stock issuance to finance its growth or to offset larger-than-expected loan losses. Adopting a mutual holding company structure gives some flexibility in raising capital, as the subsidiary of a mutual holding company may issue some of its stock to the public. U.S. mutual savings institutions have their origins in two main forms: mutual savings banks and mutual savings and loan associations. Although these institutional types began some- what distinct from one another in the early 19th century, they became structurally and functionally similar in the 20th century.3 Consequently, this paper follows the convention of referring to both types of institutions simply as mutuals.4 Three features of mutuals distinguish them from the broader banking industry. -

Credit Union to Mutual Conversion: Do Rates Diverge?

Credit Union to Mutual Conversion: Do Rates Diverge? By Jeff Heinrich and Russ Kashian Working Paper 06 - 01 University of Wisconsin – Whitewater Department of Economics 4th Floor Carlson Hall 800 W. Main Street Whitewater, WI 53538 Tel: (262) 472 -1361 DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION, Feb 13, 2006 Credit Union to Mutual Conversion: Do Rates Diverge? Jeff Heinrich University of Wisconsin-Whitewater [email protected] Russ Kashian University of Wisconsin-Whitewater [email protected] 0 DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION, Feb 13, 2006 Credit Union to Mutual Conversion: Do Rates Diverge? Abstract: This study conducts a cross-sectional analysis of 175 depository institutions, assessing the impact on the interest rates charged on loan products and offered on savings products by the size of the institution, its liquidity, its net worth, its tax and salary payments, and its status as a for-profit institution, a credit union, or a converted credit union. We find that banks and converted credit unions have interest rates significantly less favorable for consumers than credit unions, suggesting that a credit union converting will result in adverse interest rate movements for its customers. Field Code: G2 1 DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION, Feb 13, 2006 1. INTRODUCTION In a recent directive, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) proposed that a converting credit union include the following disclosures in each written communication it sends members regarding conversion: “Credit union directors and committee members serve on a volunteer basis. Directors of a mutual savings bank are compensated. Credit unions are exempt from federal tax and most state taxes.