Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

Verifying Modeling and Audiovisual Stimuli As Strategies for Mastering Guedes Peixoto's Maracatú

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School July 2019 Verifying Modeling and Audiovisual Stimuli as Strategies for Mastering Guedes Peixoto's Maracatú Rodrigo Clementino Diniz Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Clementino Diniz, Rodrigo, "Verifying Modeling and Audiovisual Stimuli as Strategies for Mastering Guedes Peixoto's Maracatú" (2019). LSU Master's Theses. 4977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4977 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VERIFYING MODELING AND AUDIOVISUAL STIMULI AS STRATEGIES FOR MASTERING GUEDES PEIXOTO´S MARACATÚ A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The School of Music by Rodrigo Clementino Diniz B.M., Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 2003 August 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, my gratitude to Olorum and Orunmila, who endowed me with intelligence, health, tenacity and musical talent, characteristics without which I possibly would not have been able to launch myself on this incredible journey. To my guardian angel, Oyá, who vibrates magnetically in me, for always being by my side, guarding me. Endless thanks to my beloved mother, Francisca Clementino, a warrior woman who gave up so much of her life to raise me by herself. -

January 20, 2008 2655Th Concert

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 6:oo pm. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. Please note that late entry or reentry of The Sixty-sixth Season of the West Building after 6:30 pm is not permitted. The William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin Concerts National Gallery of Art 2,655th Concert Music Department National Gallery of Art Jeni Slotchiver, pianist Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw Washington, DC Mailing address 2000b South Club Drive January 20, 2008 Landover, md 20785 Sunday Evening, 6:30 pm West Building, West Garden Court www.nga.gov Admission free Program Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) Bachianas brasileiras no. 4 (1930-1941) Preludio (Introdu^ao) (Prelude: Introduction) Coral (Canto do sertao) (Chorale: Song of the Jungle) Aria (Cantiga) (Aria: Song) Dansa (Miudinho) (Dance: Samba Step) Francisco Mignone (1897-1986) Sonatina no. 4 (1949) Allegretto Allegro con umore Carlos Guastavino (1912-2000) Las Ninas (The Girls) (1951) Bailecito (Dance) (1941) Gato (Cat) (1940) Camargo Guarnieri (1907-1993) Dansa negra (1948) Frutuoso de Lima Viana (1896-1976) Coiia-Jaca (Brazilian Folk Dance) (1932) INTERMISSION Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) The Musician Indian Diary: Book One (Four Studies on Motifs of the Native American Indians) (1915) Pianist Jeni Slotchiver began her formal musical studies at an early age. A He-Hea Katzina Song (Hopi) recipient of several scholarships, she attended the Interlochen Arts Academy Song of Victory (Cheyenne) and the Aspen Music Festival, before earning her bachelor and master of Blue Bird Song (Pima) and Corn-Grinding Song (Lagunas) music degrees in piano performance at Indiana University. -

![Superimposed Subdivisions (Polyrhythm Hell) [Sallan Tarkistama]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6794/superimposed-subdivisions-polyrhythm-hell-sallan-tarkistama-226794.webp)

Superimposed Subdivisions (Polyrhythm Hell) [Sallan Tarkistama]

HEIKKI MALMBERG Superimposed Subdivisions (Polyrhythm Hell) Polyrhythms or Polymeters? Usually when musicians talk about polyrhythms, they refer to rhythmic structures that are made of two or more simultaneous time signatures, in which the secondary (superimposed) time signature basically revolves around the dominant time signature. I suggest that we use the term polymeter in such cases, and use the term polyrhythm solely in situations where there are two or more subdivisions happening in the same time interval (e.g. eight note triplets over sixteenth notes). Here’s a simple example of a polymeter where the bass drum plays in 5/16 while the hands keep common (4/4) time. 3 3 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 3 5 5 5 5 And here’s a not so simple example of polyrhythms using eight notes, eight/quarter note triplets and sixteenth note quintuplets. So What Should I Do? In order to learn to play any two subdivisions against each other, or rather superimpose them if you will, you should get a reference of how they sound played simultaneously on one instrument (A good teacher and a sequencer are of paramount help here), and learn to phonetically mimic the result. You can make up halfwitted sentences or just blabber away with any foolish sounds that you come up with. as long as you’re mimicking the rhythm, it doesn’t matter. 3 3 3 3 or cold cup of tea blah bla da blah Here’s two subdivisions Here they have Here’s their daily dialog after waiting to get married. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen's Mikrophonie I and Saariaho's Six Japanese Gardens Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9b10838z Author Keelaghan, Nikolaus Adrian Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen‘s Mikrophonie I and Saariaho‘s Six Japanese Gardens A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan 2016 © Copyright by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen‘s Mikrophonie I and Saariaho‘s Six Japanese Gardens by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Robert Winter, Chair The origins of electroacoustic music are rooted in a long-standing tradition of non-human music making, dating back centuries to the inventions of automaton creators. The technological boom during and following the Second World War provided composers with a new wave of electronic devices that put a wealth of new, truly twentieth-century sounds at their disposal. Percussionists, by virtue of their longstanding relationship to new sounds and their ability to decipher complex parts for a bewildering variety of instruments, have been a favored recipient of what has become known as electroacoustic music. -

Brazilian Nationalistic Elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2006 Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda Maria Jose Bernardes Di Cavalcanti Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Di Cavalcanti, Maria Jose Bernardes, "Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda" (2006). LSU Major Papers. 39. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/39 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRAZILIAN NATIONALISTIC ELEMENTS IN THE BRASILIANAS OF OSVALDO LACERDA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti B.M., Universidade Estadual do Ceará (Brazil), 1987 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2006 © Copyright 2006 Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This monograph is dedicated to my husband Liduino José Pitombeira de Oliveira, for being my inspiration and for encouraging me during these years -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

OS COMPOSITORES E SEU TEMPO Normando Carneiro

Normando Carneiro OS COMPOSITORES E SEU TEMPO Normando Carneiro Natal 2018 1 Os Compositores de seu tempo Normando Carneiro Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741) Compositor e violinista italiano, o mais influente de sua época. Nasceu em 04/03/1678 em Veneza, estudou com seu pai, violinista na catedral de San Marcos. Ordenou-se sacerdote em 1703, chamavam-no interprete russo (o cura ruivo), e começou a ensinar no Ospedale della Pietá que era um estabelecimento para meninas órfãs. Trabalhou ali como diretor musical até 1740, como professor e compunha concertos e oratórios para os concertos semanais através dos que conseguiu uma fama internacional. A partir de 1713 Vivaldi também trabalhou como compositor e empresário de óperas em Veneza e viajava a Roma, Mantua e outras cidades para supervisionar as representações de suas óperas. Para 1740 entrou ao serviço do corte do imperador Carlos VI em Viena. Faleceu nesta cidade o 28 de julho de 1741. Composições Vivaldi escreveu mais de 500 concertos e 70 sonatas, 45 óperas, música religiosa como o oratório Judithatriumphans (1716), a Glória em re (1708), missas e motetes. Suas sonatas instrumentais são mais conservadoras que seus concertos e sua música religiosa com frequencia reflete o estilo operístico da época e a alternância de orquestra e solistas que ajudou a introduzir nos concertos. Johann SebastianBach, contemporâneo seu, embora algo mais jovem, estudou a obra de Vivaldi em seus anos de formação e de alguns dos concertos para violino e sonatas de Vivaldi só existem as transcrições (em sua maior parte para clavecín) de Bach. 2 Os Compositores de seu tempo Normando Carneiro Johann Sebastian Bach (Eisenach, 21/03/1685 — Leipzig, 28/07/1750) Compositor, cravista, Kapellmeister, regente, organista, professor violinista e violista oriundo do Sacro Império Romano-Germânico, atual Alemanha. -

DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS COURSE TITLE: Music Theory IV

SYLLABUS DATE OF LAST REVIEW: 12/2019 CIP CODE: 24.0101 SEMESTER: DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS COURSE TITLE: Music Theory IV COURSE NUMBER: MUSC0214 CREDIT HOURS: 4 INSTRUCTOR: DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS OFFICE LOCATION: DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS OFFICE HOURS: DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS TELEPHONE: DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS EMAIL: DEPARTMENTAL SYLLABUS KCKCC issued email accounts are the official means for electronically communicating with our students. PREREQUISITES: MUSC0213 Music Theory III REQUIRED TEXT AND MATERIALS: Please check with the KCKCC bookstore, http://www.kckccbookstore.com/, for the required texts for your particular class. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The purpose of this course is to continue the studies begun in Music Theory I, II and III. This course will complete the study of chromatic harmony and include a complete study of twentieth-century theoretical techniques. Topics covered will include enharmonic modulation, Impressionism, modes, scales, twelve tone techniques, and quartal harmony, and other twentieth century materials, plus elements of musicianship including sightsinging, dictation, rhythm, and keyboard skills. METHOD OF INSTRUCTION: A variety of instructional methods may be used depending on content area. These include but are not limited to: lecture, multimedia, cooperative/collaborative learning, labs and demonstrations, projects and presentations, speeches, debates, and panels, conferencing, performances, and learning experiences outside the classroom. Methodology will be selected to best meet student needs. COURSE OUTLINE: I. Enharmonic modulation A. Introduction B. Using dominant sevenths and German sixths C. Using fully diminished seventh chords D. Spelling and recognizing fully diminished seventh chords E. Resolution of fully diminished seventh chords II. Modes A. Modes in the Middles Ages B. Authentic vs. plagal modes C. Modes in the Renaissance D. -

Gershwin, Copland, Lecuoña, Chávez, and Revueltas

Latin Dance-Rhythm Influences in Early Twentieth Century American Music: Gershwin, Copland, Lecuoña, Chávez, and Revueltas Mariesse Oualline Samuels Herrera Elementary School INTRODUCTION In June 2003, the U. S. Census Bureau released new statistics. The Latino group in the United States had grown officially to be the country’s largest minority at 38.8 million, exceeding African Americans by approximately 2.2 million. The student profile of the school where I teach (Herrera Elementary, Houston Independent School District) is 96% Hispanic, 3% Anglo, and 1% African-American. Since many of the Hispanic students are often immigrants from Mexico or Central America, or children of immigrants, finding the common ground between American music and the music of their indigenous countries is often a first step towards establishing a positive learning relationship. With this unit, I aim to introduce students to a few works by Gershwin and Copland that establish connections with Latin American music and to compare these to the works of Latin American composers. All of them have blended the European symphonic styles with indigenous folk music, creating a new strand of world music. The topic of Latin dance influences at first brought to mind Mexico and mariachi ensembles, probably because in South Texas, we hear Mexican folk music in neighborhood restaurants, at weddings and birthday parties, at political events, and even at the airports. Whether it is a trio of guitars, a group of folkloric dancers, or a full mariachi band, the Mexican folk music tradition is part of the Tex-Mex cultural blend. The same holds true in New Mexico, Arizona, and California. -

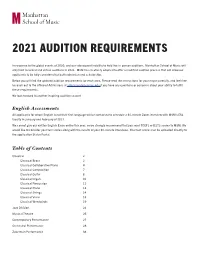

2021 Audition Requirements

2021 AUDITION REQUIREMENTS In response to the global events of 2020, and our subsequent inability to hold live in-person auditions, Manhattan School of Music will only hold recorded and virtual auditions in 2021. MSM has creatively adapted to offer a modified audition process that will allow our applicants to be fully considered for both admission and scholarship. Below you will find the updated audition requirements for each area. Please read the instructions for your major carefully, and feel free to reach out to the Office of Admissions at [email protected] if you have any questions or concerns about your ability to fulfill these requirements. We look forward to another inspiring audition season! English Assessments All applicants for whom English is not their first language will be contacted to schedule a 30-minute Zoom interview with MSM’s ESL faculty in January and February of 2021. We cannot give our written English Exam online this year, so we strongly recommend that you send TOEFL or IELTS scores to MSM. We would like to consider your test scores along with the results of your 30-minute interviews. Your test scores can be uploaded directly to the application Status Portal. Table of Contents Classical 2 Classical Brass 2 Classical Collaborative Piano 4 Classical Composition 7 Classical Guitar 8 Classical Organ 10 Classical Percussion 11 Classical Piano 13 Classical Strings 14 Classical Voice 18 Classical Woodwinds 19 Jazz Division 24 Musical Theatre 26 Contemporary Performance 27 Orchestral Performance 28 Zukerman Performance 34 CLASSICAL BRASS Audition Format Applicants will submit the required repertoire listed below as separate video recordings by February 1, 2021.