Chapter 2 NC Beginnings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

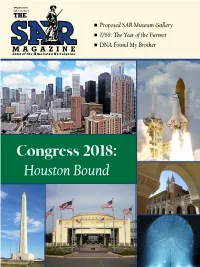

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

1 the Story of the Faulkner Murals by Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. the Story Of

The Story of the Faulkner Murals By Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. The story of the Faulkner murals in the Rotunda begins on October 23, 1933. On this date, the chief architect of the National Archives, John Russell Pope, recommended the approval of a two- year competing United States Government contract to hire a noted American muralist, Barry Faulkner, to paint a mural for the Exhibit Hall in the planned National Archives Building.1 The recommendation initiated a three-year project that produced two murals, now viewed and admired by more than a million people annually who make the pilgrimage to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to view two of the Charters of Freedom documents they commemorate: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America. The two-year contract provided $36,000 in costs plus $6,000 for incidental expenses.* The contract ended one year before the projected date for completion of the Archives Building’s construction, providing Faulkner with an additional year to complete the project. The contract’s only guidance of an artistic nature specified that “The work shall be in character with and appropriate to the particular design of this building.” Pope served as the contract supervisor. Louis Simon, the supervising architect for the Treasury Department, was brought in as the government representative. All work on the murals needed approval by both architects. Also, The United States Commission of Fine Arts served in an advisory capacity to the project and provided input critical to the final composition. The contract team had expertise in art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. -

An Educator's Guide to the Story of North Carolina

Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide An Educator’s Guide to The Story of North Carolina An exhibition content guide for teachers covering the major themes and subject areas of the museum’s exhibition The Story of North Carolina. Use this guide to help create lesson plans, plan a field trip, and generate pre- and post-visit activities. This guide contains recommended lessons by the UNC Civic Education Consortium (available at http://database.civics.unc.edu/), inquiries aligned to the C3 Framework for Social Studies, and links to related primary sources available in the Library of Congress. Updated Fall 2016 1 Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide The earth was formed about 4,500 million years (4.5 billion years) ago. The landmass under North Carolina began to form about 1,700 million years ago, and has been in constant change ever since. Continents broke apart, merged, then drifted apart again. After North Carolina found its present place on the eastern coast of North America, the global climate warmed and cooled many times. The first single-celled life-forms appeared as early as 3,800 million years ago. As life-forms grew more complex, they diversified. Plants and animals became distinct. Gradually life crept out from the oceans and took over the land. The ancestors of humans began to walk upright only a few million years ago, and our species, Homo sapiens, emerged only about 120,000 years ago. The first humans arrived in North Carolina approximately 14,000 years ago—and continued the process of environmental change through hunting, agriculture, and eventually development. -

American Self-Government: the First & Second Continental Congress

American Self-Government: The First and Second Continental Congress “…the eyes of the virtuous all over the earth are turned with anxiety on us, as the only depositories of the sacred fire of liberty, and…our falling into anarchy would decide forever the destinies of mankind, and seal the political heresy that man is incapable of self-government.” ~ Thomas Jefferson Overview Students will explore the movement of the colonies towards self-government by examining the choices made by the Second Continental Congress, noting how American delegates were influenced by philosophers such as John Locke. Students will participate in an activity in which they assume the role of a Congressional member in the year 1775 and devise a plan for America after the onset of war. This lesson can optionally end with a Socratic Seminar or translation activity on the Declaration of Independence. Grades Middle & High School Materials • “American Self Government – First & Second Continental Congress Power Point,” available in Carolina K- 12’s Database of K-12 Resources (in PDF format): https://k12database.unc.edu/wp- content/uploads/sites/31/2021/01/AmericanSelfGovtContCongressPPT.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode” o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] • The Bostonians Paying the Excise Man, image attached or available in power point • The Battle of Lexington, image attached or available in power -

From Red Shirts to Research: the Question of Progressivism in North Carolina, 1898 to 1959

From Red Shirts to Research: The Question of Progressivism in North Carolina, 1898 to 1959 by Calen Randolph Clifton, 2013 CTI Fellow Martin Luther King, Jr. Middle School This curriculum unit is recommended for: 8th Grade Social Studies North Carolina: The Creation of the State and Nation Keywords: Progressivism, race relations, business, Great Depression, civil rights, Charlotte, desegregation, textile mills, sharecropping Teaching Standards: 8.H.2.2, 8.H.3.3, 8.C&G.1.3, 8C&G1.4 Synopsis: This unit is designed to build student skills of independent analysis and inquiry. Beginning with the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 and ending with the creation of Research Triangle Park in 1959, students will come to their own understanding of the progressive nature of North Carolina’s past. I plan to teach this unit during the coming year in to 111 students in 8th Grade Social Studies, North Carolina: The Creation of the State and Nation. I give permission for the Institute to publish my curriculum unit and synopsis in print and online. I understand that I will be credited as the author of my work. From Red Shirts to Research: The Question of Progressivism in North Carolina, 1898 to 1959 Calen Randolph Clifton Introduction The concept of progressivism is hard to grasp. In a literal sense, progressivism is the idea that advances in a society can improve the quality of life experienced by the members of that society. However, the ways in which different individuals and groups view "progress" can be paradoxical. This is especially true in societies that are struggling with internal strife and discord. -

North Carolina Digital Collections

North Carolina suggestions for apply- ing the social studies ©IiF IGtbrarg nf thf llntorsitij nf Nnrtlt (Uarnlttia Plyilantltrnjiif ^nmtira NORTH CAROLINA SUGGESTIONS FOR APPLYING THE SOCIAL STUDIES Issued by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction Raleigh, North Carolina THE STATE FLAG The model of the flag as used today was adopted in 188 5. It consists of a blue union containing in the center thereof a white star with the letter N in gilt on the left and the letter C in gilt on the right of the star. The fly of the flag consists of two equally proportional bars, the upper bar red and the lower bar white. The length of these bars is equal to the perpendicular length of the union, and the total length of the flag is one-third more than its width. Above the star in the center of the union is a gilt scroll in semi-circular form, containing in black the inscription: "May 20, 1775," and below the star is a similar scroll containing the inscription: "April 12, 1776." This first date was placed on the flag to mark the signing of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. The second date marks the day on which the Halifax Convention empowered the North Carolina members of the Continental Congress to concur with the delegates of the other colo- nies in declaring independence. Publication No. 217 NORTH CAROLINA SUGGESTIONS FOR APPLYING THE SOCIAL STUDIES Issued by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction Raleigh, North Carolina 1939 Bayard Wootten. HAYES The former home of Samuel Johnston, Revolutionary leader, Governor, and United States Senator, is located at Edenton. -

Mecklenburg Resolves

The Mecklenburg Resolves Overview Students will examine the Mecklenburg Resolves and work in small groups to teach their classmates about the key ideas posed in the document. Students will then demonstrate their understanding of this document by creating innovative infomercials on the important elements of the Resolves. Students will also explore the limitations of the society that created the Mecklenburg Resolves, given that over 500,000 people were enslaved at the time. Grades 4-8 Materials • Image of the NC State Flag, attached • Excerpt from The Mecklenburg Resolves, attached • Dictionaries or Internet access Essential Questions: • What was the purpose of the Mecklenburg Resolves? • What effect did the Mecklenburg Resolves, the Halifax Resolves, and the Declaration of Independence have on colonists in regards to the Revolutionary War? • How could the authors of the Mecklenburg Resolves as well as the Declaration of Independence write these words and profess these ideals while supporting slavery? Duration 1-2 class periods Student Preparation Students should have a basic understanding of pre-Revolutionary tensions between the British and colonists, as well as the causes of the battles of Lexington and Concord. Procedure The North Carolina State Flag 1. As a warm-up, project an image of the North Carolina state flag (attached). Ask students to share what they know about the flag. Particularly, ask students if they can explain the significance of the two dates on the flag. (May 20, 1775 notes the date of the Mecklenburg Resolves and April 12, 1776 notes the date of the Halifax Resolves.) 2. Ask students to raise their hand if they have ever heard of the Mecklenburg Resolves. -

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, the Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, The Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They Are Democrats, The Target Is Black Democrats. The Constant Is Race. A Report for League of Women Voters v. North Carolina By J. Morgan Kousser Table of Contents Section Title Page Number I. Aims and Methods 3 II. Abstract of Findings 3 III. Credentials 6 IV. A Short History of Racial Discrimination in North Carolina Politics A. The First Disfranchisement 8 B. Election Laws and White Supremacy in the Post-Civil War South 8 C. The Legacy of White Political Supremacy Hung on Longer in North Carolina than in Other States of the “Rim South” 13 V. Democratizing North Carolina Election Law and Increasing Turnout, 1995-2009 A. What Provoked H.B. 589? The Effects of Changes in Election Laws Before 2010 17 B. The Intent and Effect of Election Laws Must Be Judged by their Context 1. The First Early Voting Bill, 1993 23 2. No-Excuse Absentee Voting, 1995-97 24 3. Early Voting Launched, 1999-2001 25 4. An Instructive Incident and Out-of-Precinct Voting, 2005 27 5. A Fair and Open Process: Same-Day Registration, 2007 30 6. Bipartisan Consensus on 16-17-Year-Old-Preregistration, 2009 33 VI. Voter ID and the Restriction of Early Voting: The Preview, 2011 A. Constraints 34 B. In the Wings 34 C. Center Stage: Voter ID 35 VII. H.B. 589 Before and After Shelby County A. Process Reveals Intention 37 B. Facts 1. The Extent of Fraud 39 2. -

National Statuary Hall Collection: Background and Legislative Options

National Statuary Hall Collection: Background and Legislative Options Updated December 3, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42812 National Statuary Hall Collection: Background and Legislative Options Summary The National Statuary Hall Collection, located in the U.S. Capitol, comprises 100 statues provided by individual states to honor persons notable for their historic renown or for distinguished services. The collection was authorized in 1864, at the same time that Congress redesignated the hall where the House of Representatives formerly met as National Statuary Hall. The first statue, depicting Nathanael Greene, was provided in 1870 by Rhode Island. The collection has consisted of 100 statues—two statues per state—since 2005, when New Mexico sent a statue of Po’pay. At various times, aesthetic and structural concerns necessitated the relocation of some statues throughout the Capitol. Today, some of the 100 individual statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection are located in the House and Senate wings of the Capitol, the Rotunda, the Crypt, and the Capitol Visitor Center. Legislation to increase the size of the National Statuary Hall Collection was introduced in several Congresses. These measures would permit states to furnish more than two statues or allow the District of Columbia and the U.S. territories to provide statues to the collection. None of these proposals were enacted. Should Congress choose to expand the number of statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection, the Joint Committee on the Library and the Architect of the Capitol (AOC) may need to address statue location to address aesthetic, structural, and safety concerns in National Statuary Hall, the Capitol Visitor Center, and other areas of the Capitol. -

Did You Know? North Carolina

Did You Know? North Carolina Discover the history, geography, and government of North Carolina. The Land and Its People The state is divided into three distinct topographical regions: the Coastal Plain, the Piedmont Plateau, and the Appalachian Mountains. The Coastal Plain affords opportunities for farming, fishing, recreation, and manufacturing. The leading crops of this area are bright-leaf tobacco, peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. Large forested areas, mostly pine, support pulp manufacturing and other forest-related industries. Commercial and sport fishing are done extensively on the coast, and thousands of tourists visit the state’s many beaches. The mainland coast is protected by a slender chain of islands known as the Outer Banks. The Appalachian Mountains—including Mount Mitchell, the highest peak in eastern America (6,684 feet)—add to the variety that is apparent in the state’s topography. More than 200 mountains rise 5,000 feet or more. In this area, widely acclaimed for its beauty, tourism is an outstanding business. The valleys and some of the hillsides serve as small farms and apple orchards; and here and there are business enterprises, ranging from small craft shops to large paper and textile manufacturing plants. The Piedmont Plateau, though dotted with many small rolling farms, is primarily a manufacturing area in which the chief industries are furniture, tobacco, and textiles. Here are located North Carolina’s five largest cities. In the southeastern section of the Piedmont—known as the Sandhills, where peaches grow in abundance—is a winter resort area known also for its nationally famous golf courses and stables. -

FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY July 1963

The FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY V OLUME XLII July 1963 - April 1964 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XLII Adams, Adam G., book review by, 389 African Colonization Movement, by Staudenraus, reviewed, 184 Alabama Confederate Reader, by McMillan, reviewed, 389 Alexander, E. P., Military Memoirs of a Confederate, ed. by Williams, reviewed, 70 Allen, Edison B., book review by, 72 “Alonso Solana Map of Florida, 1683,” by Luis Rafael Arana, 258 Ambrose, Stephen E., Halleck: Lincoln’s Chief of Staff, reviewed, 71 American College and University: A History, by Rudolph, re- viewed, 284 Anderson, Bern, By Sea and by River: The Naval History of the Civil War, reviewed, 276 Anderson, Robert L., “The End of an Idyll,” 35 “Annual Meeting, Sarasota, May 2-4, 1963,” 159 Ante-Bellum Southern Literary Critics, by Parks, reviewed, 183 Ante-Bellum Thomas County, 1825-1861, by Rogers, reviewed, 380 Arana, Eugenia B., Doris C. Wiles, and Cecil D. Eby, Jr., “Mem- oir of a West Pointer in St. Augustine, 1824-1826,” 307 Arana, Luis Rafael, “The Alonso Solana Map of Florida, 1683,” 258 Arnade, Charles W., “Recent Problems of Florida History,” 1; book reviews by, 60, 178 Barrett, John G., book review by, 71 Barry, John, Hillsborough: A Parish in the Ulster Plantation, reviewed, 268 Bearss, Edwin C., “Military Operations on the St. Johns, Sep- tember-October 1862 (Part I): The Union Navy Fails to Drive The Confederates from St. Johns Bluff,” 232; “Military Operations on the St. Johns, September-October 1862 (Part II): The Federals Capture St. Johns Bluff,” 331 “Beast” Butler, by Wehrlich, reviewed, 72 Bellwood, Ralph, Tales of West Pasco, reviewed, 57 Bethell, John A., Bethell’s History of Point Pinellas, reviewed, 56 Bethell’s History of Point Pinellas, reviewed, 56 Blassingame, Wyatt, book review by, 372 “Book Notes,” 288 Bonner. -

Legacy Commission

Legacy Commission History is about what happened in the past while commemoration is about the present. We put up statues and celebrate holidays to honor figures from the past who embody some quality we admire….as society changes, the qualities we care about shift. Heather Cox Richardson, Historian Introduction In the 21st century, Charlotte is a city that is growing fast, simultaneously becoming more racially and ethnically diverse and socioeconomically disparate. A mosaic of longtime residents and newcomers from across the U.S. and around the world creates both a dynamic cultural landscape and new challenges that force us to consider issues of equity and inclusion. There is a legacy of racial discrimination in Charlotte that has denied African Americans and other people of color the opportunities to participate fully in the city’s government, civic life, economy and educational advancement. Vestiges of this legacy are symbolically represented in streets, monuments, and buildings named in honor of slave owners, champions of the Confederacy, and proponents of white supremacy. The Legacy Commission believes that the continued memorialization of slave owners, Confederate leaders, and white supremacists on street signs does not reflect the values that Charlotte upholds today and is a direct affront to descendants of the enslaved and oppressed African Americans who labored to build this city. The Commission recommends changing street names and reimagining civic spaces to create a new symbolic landscape that is representative of the dynamic and diverse city Charlotte has become and reflective of the inclusive vision it strives to achieve. The Charge Engage in a comprehensive study of street names and monuments in the City of Charlotte that honor a legacy of Confederate soldiers, slave owners and segregationists.