Foundation House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report FY17-18

2017/18 The Rhodes Trust Second Century Annual Report 2017/18 Trustees 2017/18 Sir John Hood KNZM, Chairman Professor Margaret Professor Ngaire Woods CBE (New Zealand & Worcester 1976) MacMillan CH, CC (New Zealand & Balliol 1987) Andrew Banks Dr Tariro Makadzange John Wylie AM (Florida & St Edmund Hall 1976) (Zimbabwe & Balliol 1999) (Queensland & Balliol 1983) Dominic Barton Michael McCaffery (British Columbia & Brasenose 1984) (Pennsylvania & Merton 1975) New Trustees 2018 Professor Sir John Bell GBE John McCall MacBain O.C. Robert Sternfels (Alberta & Magdalen 1975) (Québec & Wadham 1980) (California & Worcester 1992) Professor Elleke Boehmer Nicholas Oppenheimer Katherine O’Regan (South Africa-at-Large and St John’s 1985) Professor Dame Carol Robinson DBE Dame Helen Ghosh DCB Trustee Emeritus Dilip Shangvhi Donald J. Gogel Julian Ogilvie Thompson (New Jersey & Balliol 1971) Peter Stamos (Diocesan College, Rondebosch (California & Worcester 1981) & Worcester 1953) Glen James Judge Karen Stevenson (Maryland/DC & Magdalen 1979) Development Committee Andrew Banks, Chairman Bruns Grayson The Hon. Thomas McMillen (Florida & St Edmund Hall 1976) (California & University 1974) (Maryland & University 1974) Nicholas Allard Patrick Haden Timothy Orton (New York & Merton 1974) (California & Worcester 1975) (Australia-at-Large & Magdalen 1986) Dominic Barton Sir John Hood KNZM Lief Rosenblatt (British Columbia & Brasenose 1984) (New Zealand & Worcester 1976) (Massachusetts & Magdalen 1974) Shona L. Brown Sean Mahoney Arthur Scace, CM, QC, LLD (Ontario & New College 1987) (Illinois & New College 1984) (Ontario & Corpus Christi 1961) Gerald J. Cardinale Jacko Maree The Hon. Malcolm Turnbull MP (Pennsylvania & Christ Church 1989) (St Andrews College, Grahamstown (New South Wales & Brasenose 1978) & Pembroke 1978) Sir Roderick Eddington Michele Warman (Western Australia & Lincoln 1974) Michael McCaffery (New York & Magdalen 1982) (Pennsylvania & Merton 1975) Michael Fitzpatrick Charles Conn (Western Australia & St Johns 1975) John McCall MacBain O.C. -

The Supreme Court of Victoria

ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL Annual Report Supreme Court a SUPREME COURTSUPREME OF VICTORIA 2016-17 of Victoria SUPREME COURTSUPREME OF VICTORIA ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17ANNUAL Supreme Court Annual Report of Victoria 2016-17 Letter to the Governor September 2017 To Her Excellency Linda Dessau AC, Governor of the state of Victoria and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia. Dear Governor, We, the judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria, have the honour of presenting our Annual Report pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial year 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. Yours sincerely, Marilyn L Warren AC The Honourable Chief Justice Supreme Court of Victoria Published by the Supreme Court of Victoria Melbourne, Victoria, Australia September 2017 © Supreme Court of Victoria ISSN 1839-6062 Authorised by the Supreme Court of Victoria. This report is also published on the Court’s website: www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au Enquiries Supreme Court of Victoria 210 William Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Tel: 03 9603 6111 Email: [email protected] Annual Report Supreme Court 1 2016-17 of Victoria Contents Chief Justice foreword 2 Court Administration 49 Discrete administrative functions 55 Chief Executive Officer foreword 4 Appendices 61 Financial report 62 At a glance 5 Judicial officers of the Supreme Court of Victoria 63 About the Supreme Court of Victoria 6 2016-17 The work of the Court 7 Judicial activity 65 Contacts and locations 83 The year in review 13 Significant events 14 Work of the Supreme Court 18 The Court of Appeal 19 Trial Division – Commercial Court 23 Trial Division – Common Law 30 Trial Division – Criminal 40 Trial Division – Judicial Mediation 45 Trial Division – Costs Court 45 2 Supreme Court Annual Report of Victoria 2016-17 Chief Justice foreword It is a pleasure to present the Annual Report of the Supreme Court of Victoria for 2016-17. -

The Hon. Linda Dessau AC Government House Melbourne Victoria 3004 Australia

GOVERNOR OF VICTORIA A MESSAGE FROM HER EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR OF VICTORIA THE HON LINDA DESSAU AC The start to 2020 has certainly been a difficultone, with the bushfiresthat caused so much destruction in parts of our State, and now COVID-19. Our thoughts are with those in areas still grappling with rebuilding and recovery from the fires. And, indeed, with everyone, as we all now try to cope with this health challenge and its far-reachingeffects. We know that in recent months, as in the past, Victorians have demonstrated their resilience and their generosity in response to the bushfirecrisis. Now, more than ever, we need to pull together, to follow the advice and rules set by the experts, to be calm and clear-headed and to be mindful of each other's safety and needs. As our opportunities for workplace and social contact diminish, each one of us will feel the effectsin different ways. To greater or lesser extents, we might all feel some sense of dislocation. I encourage you to check on family, neighbours, the elderly, workmates and anyone who might be alone or doing it tough. Physical distance need not mean social isolation. Let's keep working on creative ways to keep in touch with each other. My husband, Tony, joins me in these thoughts and in particular in expressing our gratitude to the many Victorians working on the frontline - not only our medical and emergency workers but all those working to care for the vulnerable, to look after our children, to keep essential services running and to respond to this unfolding situation. -

Victorian Honour Roll of Women

INSPIRATIONAL WOMEN FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE OF WALKS ALL FROM WOMEN INSPIRATIONAL VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE I VICTORIAN HONOUR To receive this publication in an accessible format phone 03 9096 1838 ROLL OF WOMEN using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email Women’s Leadership [email protected] Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. © State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services March, 2018. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Where the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used it refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous/Koori/Koorie is retained when it is part of the title of a report, program or quotation. ISSN 2209-1122 (print) ISSN 2209-1130 (online) PAGE II PAGE Information about the Victorian Honour Roll of Women is available at the Women Victoria website https://www.vic.gov.au/women.html Printed by Waratah Group, Melbourne (1801032) VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 2018 WOMEN OF ROLL HONOUR VICTORIAN VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 1 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 2 CONTENTS THE 4 THE MINISTER’S FOREWORD 6 THE GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD 9 2O18 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN INDUCTEES 10 HER EXCELLENCY THE HONOURABLE LINDA DESSAU AC 11 DR MARIA DUDYCZ -

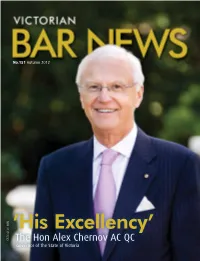

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

The Honourable Linda Dessau AM, Governor of Victoria to Deliver Lecture on Sport and the Arts at State Library Victoria

20 January 2016 The Honourable Linda Dessau AM, Governor of Victoria to deliver lecture on sport and the arts at State Library Victoria The Honourable Linda Dessau AM, Governor of Victoria will deliver this year’s first Big Ideas under the dome lecture – “Sport and the arts: From Ablett (Jnr) to Caravaggio” - at State Library Victoria on Wednesday 17 February. “It’s a paradox that when we live in a State that loves both sport and the arts, so many people seem to show discomfort in saying that they love them both. There is frequently an abyss of misunderstanding between two distinct camps: those who are devoted to sport, and those who love the arts. The real argument should be about why sport really matters and why the arts really matter and why both really matter” The Hon. Linda Dessau AM Governor of Victoria Governor Dessau is Victoria’s 29th Governor and the first female in the role. Her Excellency was previously a Judge of the Family Court of Australia and immediately before her appointment as Governor, she was President of the Melbourne Festival, Chair of the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Victorian Regional Committee and a national Board member of the Trust, a Commissioner of the Australian Football League, a Trustee of the National Gallery of Victoria, a Board member and former Chair of AFL Sportsready and Artsready, a Board member of the Unicorn Foundation, and a Patron of Sports Connect. Big Ideas under the dome is a thought-provoking lecture series that features great minds in the arts, culture, social justice, science and leadership as they discuss, debate and reflect on the big ideas and issues of our time. -

Annual Report: 2015–16

Annual ReportAnnual 2015–16 Library Board of Victoria Board Library Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 2015–16 Contents 2 President’s report 4 Chief Executive Officer’s year in review 6 Vision and values 7 Report of operations 22 Financial summary 24 2015–16 key performance indicators 24 Service Agreement with the Minister for Creative Industries 25 Output framework 27 Acquisitions statistics 2015–16 28 Library Board and corporate governance 33 Library Executive 34 Organisational structure 35 Reconciliation of executive officers 36 Major contracts 36 Victorian Industry Participation Policy 36 National Competition Policy 36 Compliance with the Building Act 1993 37 Financial information 38 Occupational health and safety performance measures 39 Public sector values and employment principles 40 Statement of workforce data and merit and equity 41 Environmental performance 42 Freedom of information 43 Protected Disclosure Act 2012 43 Disability Action Plan 43 Government advertising expenditure 44 Consultancies 45 Risk attestation Financial statements 47 Auditor-General’s report 49 Library Board of Victoria letter 50 Financial report for year ended 30 June 2016 57 Notes to the financial statements 114 Disclosure index President’s report I am pleased to present my fifth report as the We were delighted to welcome Kate Torney as President of the Library Board of Victoria. our new Chief Executive Officer in November last year. Kate came to the Library leadership There is much good news to report. Our Vision role with more than 20 years in the information 2020 building project progresses apace – in industry, most recently as Director of News at the September last year we were thrilled that the Ian Australian Broadcasting Corporation. -

Book 9 7, 8 and 9 June 2016

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 9 7, 8 and 9 June 2016 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer Following a select committee investigation, Victorian Hansard was conceived when the following amended motion was passed by the Legislative Assembly on 23 June 1865: That in the opinion of this house, provision should be made to secure a more accurate report of the debates in Parliament, in the form of Hansard. The sessional volume for the first sitting period of the Fifth Parliament, from 12 February to 10 April 1866, contains the following preface dated 11 April: As a preface to the first volume of “Parliamentary Debates” (new series), it is not inappropriate to state that prior to the Fifth Parliament of Victoria the newspapers of the day virtually supplied the only records of the debates of the Legislature. With the commencement of the Fifth Parliament, however, an independent report was furnished by a special staff of reporters, and issued in weekly parts. This volume contains the complete reports of the proceedings of both Houses during the past session. In 2016 the Hansard Unit of the Department of Parliamentary Services continues the work begun 150 years ago of providing an accurate and complete report of the proceedings of both houses of the Victorian Parliament. The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AM The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC, QC The ministry (to 22 May 2016) Premier ......................................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education ......................... -

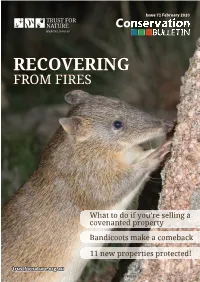

Recovering from Fires

RECOVERING FROM FIRES What to do if you’re selling a covenanted property Bandicoots make a comeback 11 new properties protected! trustfornature.org.au Trust for Nature (Victoria) is a not-for-profit organisation that works with private landowners to protect native plants and wildlife on their land. Two-thirds of Victoria is privately owned, which means that the protection of native plants and wildlife on private land is vital. Trust for Nature has a number of different ways to support private land conservation including, conservation covenants, an ongoing land stewardship support program for all covenantors and a Revolving Fund and the purchase of land for permanent protection. Patron: The Honourable Linda Dessau AC, Governor of Victoria. Trustees: Geoff Driver (Chair), Gayle Austen, Dr Sandra Brizga, Dr Dominique Hes, Dr Charles Meredith, Nina Braid, Binda Gokhale, Matthew Kronborg, Nadine Ponomarenko, Jennifer Wolcott. Recognition of Traditional Owners: Trust for Nature recognises the continuing spiritual and cultural connection of Traditional Owners to Victoria’s land, wildlife, freshwater and saltwater environments. The Trust is committed to helping Traditional Owners conserve, restore where possible and protect natural environments, wildlife and cultural heritage values. Front cover: The nationally endangered Southern Brown Bandicoot was thought to be locally extinct in the northern Grampians. See page 15. IN THIS ISSUE Conservation science Recovering from fires We can all do something in our What we are doing to help landholders -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No

VICTORIAN No. 139 ISSN 0159-3285BAR NEWS SUMMER 2006 Appointment of Senior Counsel Welcomes: Justice Elizabeth Curtain, Judge Anthony Howard, Judge David Parsons, Judge Damien Murphy, Judge Lisa Hannon and Magistrate Frank Turner Farewell: Judge Barton Stott Charles Francis Talks of County Court Judges of Yesteryear Postcard from New York City Bar Welcomes Readers Class of 2006 Milestone for the Victorian Bar 2006–2007 Victorian Bar Council Appointment and Retirement of Barfund Board Directors Celebrating Excellence Retiring Chairman’s Dinner Women’s Legal Service Victoria Celebrates 25 Years Fratricide in Labassa Launch of the Good Conduct Guide Extending the Boundary of Right Council of Legal Education Dinner Women Barristers Association Anniversary Dinner A Cricket Story The Essoign Wine Report A Bit About Words/The King’s English Bar Hockey 3 ���������������������������������� �������������������� VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 139 SUMMER 2006 Contents EDITORS’ BACKSHEET 5 Something Lost, Something Gained 6 Appointment of Senior Counsel CHAIRMAN’S CUPBOARD 7 The Bar — What Should We be About? ATTORNEY-GENERAL’S COLUMN 9 Taking the Legal System to Even Stronger Ground Welcome: Justice Welcome: Judge Anthony Welcome: Judge David WELCOMES Elizabeth Curtain Howard Parsons 10 Justice Elizabeth Curtain 11 Judge Anthony Howard 12 Judge David Parsons 13 Judge Damien Murphy 14 Judge Lisa Hannon 15 Magistrate Frank Turner FAREWELL 16 Judge Barton Stott NEWS AND VIEWS 17 Charles Francis Talks of County Court Judges Welcome: Judge Damien Welcome: Judge -

Annual Report 2014-2015 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 CONTENTS Our Mission 01 Introducing Foundation House 03 Indigenous Acknowledgment 04 Reports from the Chair and CEO 05 Financial Report 07 Our Thanks 16 THIS REPORT: Co-ordination: Sue West, Siobhan O’Mara & Josef Szwarc Proofreading: Sue West OUR MISSION Layout: Blue Corner Creative Printing: Impact Digital To advance the health, wellbeing Foundation House 2015 Incorporation number: A0016163P This work is copyright. No part of this publication and human rights of people from may be reproduced, translated or adapted in any form without prior written permission. Apart from any use as permitted under the refugee backgrounds who have Copyright Act 1968, all other rights reserved. Requests for any use of material should be directed to: [email protected] experienced torture or other or phone (03) 9388 0022. ISBN 978-0-9874334-6-6 (Print) traumatic events. 978-0-9874334-7-3 (Electronic) 01 02 INTRODUCING INDIGENOUS FOUNDATION HOUSE ACKNOWLEDGMENT The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc. (also known as The Victorian Foundation for people and other Indigenous build respectful and informed Foundation House) provides services to people of refugee backgrounds in Survivors of Torture’s primary Victorians due to the impact of relationships with the Victorian locations at Brunswick, colonisation. We believe that Indigenous community based Victoria who have experienced torture or other traumatic events in their Dandenong, Sunshine and acknowledging the past and its on the acknowledgment of their country of origin or while fleeing those countries. Ringwood are on the traditional impact on the present is vital unique position as the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri people. -

SPECIAL Victoria Government Gazette

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 378 Thursday 9 November 2017 By Authority of Victorian Government Printer COMMISSION passed under the Public Seal of the State of Victoria appointing KENNETH DOUGLAS LAY AO APM to be Lieutenant-Governor of the State of Victoria in the Commonwealth of Australia To Kenneth Douglas Lay AO APM, Greeting: I, LINDA DESSAU AC, Governor in and over the State of Victoria and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia, under section 7 of the Australia Acts 1986 of the Commonwealth of Australia and of the United Kingdom and the Constitution Act 1975 of the State of Victoria, by this my Commission under the Public Seal of the State of Victoria, hereby appoint you, KENNETH DOUGLAS LAY AO APM to be, during the Governor’s pleasure, the Lieutenant-Governor of the State of Victoria, in the Commonwealth of Australia and you are authorised and empowered to perform the powers and functions of the Office of the Lieutenant-Governor in accordance with the Constitution Act 1975 of Victoria, the Australia Acts 1986 of the Commonwealth of Australia and of the United Kingdom, and all other applicable laws. AND this Commission shall supersede the Commission dated 4 April 2006 appointing THE HONOURABLE MARILYN LOUISE WARREN AC to be Lieutenant Governor of the State of Victoria on 9 November 2017 or, if you have not taken the prescribed Oath or Affirmation before that date, as soon as you have taken that Oath or Affirmation. AND I hereby command all Victorians and all other persons who may lawfully be required to do so to give due respect and obedience to the Lieutenant-Governor accordingly.