Diagnosis and Primary Care Management of Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glomerulosclerosis in Reflux Nephropathy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Kidney International, Vol. 21(1982), pp. 528—534 NEPHROLOGY FORUM Glomeruloscierosis in reflux nephropathy Principal discussant: RAMzI S. COTRAN Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts penis, testes, and urethral meatus were normal. The prostate was of normal size. Editors The BUN was 14 mg/dl; creatinine, 1.3 mg/dl (creatinine clearance, 113 mI/mm); blood chemistries were normal; the blood glucose was 93 JORDANJ. COHEN mg/dl; and the complement profile was normal. Serum protein was 7.5 JOHN 1. HARRINGTON gIdI with 4.3 g/dl albumin. Urinalysis showed a pH of 5; a specific JEROME P.KASSIRER gravity of 1.015; 4+ protein, no cells, and no bacteria. Urine culture was sterile. The 24-hour urine protein excretion was 2.4 g. Editor Chest x-ray showed borderline cardiomegaly with clear lungs. An Managing intravenous pyelogram revealed bilateral coarse scarring with caliecta- CHERYL J. ZUSMAN sis. The right kidney was smaller than the left. There was moderate ureterectasia extending down to the ureterovesical junction. A voiding cystourethrogram revealed a large-capacity bladder; the patient had no MichaelReese Hospital and Medical Center urge to void after almost 500 ml of contrast material was instilled. Bilateral reflux was greater and persistent on the left and was intermit- University of Chicago, tent on the right. The left ureter was dilated and tortuous. A left Pritzker School of Medicine ureterocele and right bladder diverticulum were visualized. and A biopsy of the left kidney showed focal scarring with interstitial New England Medical Center fibrosis and chronic inflammation, tubular atrophy, and dilation. -

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Relato de Caso Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: One or Two Glomerular Diseases? Glomerulosclerose Segmentar e Focal em Lúpus Eritematoso Sistêmico: Uma ou Duas Doenças? Rogério Barbosa de Deus1, Luis Antonio Moura1, Marcello Fabiano Franco2, Gianna Mastroianni Kirsztajn1 1 Nephrology Division and 2 Department of Pathology - Universidade Federal de São Paulo – EPM/UNIFESP- São Paulo. ABSTRACT Some patients with clinical and/or laboratory diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) present with nephritis which from the morphological point of view does not fit in one of the 6 classes described in the WHO classification of lupus nephritis. On the other hand, nonlupus nephritis in patients with confirmed SLE is rarely reported. This condition may not be so uncommon as it seems. The associated glomerular lesions most frequently described are amyloidosis and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). We report on a 46 year-old, caucasian woman, who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology criteria for SLE diagnosis: arthritis, positive anti-DNA, ANA, anti-Sm antibodies, and cutaneous maculae. During the follow-up, she presented arthralgias, alopecia, vasculitis, lower extremities edema and decreased serum levels of C3 and C4. Proteinuria was initially nephrotic, but reached negative levels. The serum creatinine varied from 0.7 to 3.0 mg/dl. The patient was submitted to the first renal biopsy at admission and to the second one, 3 years later, with diagnosis of minimal change disease and FSGS, respectively. No deposits were demonstrated by immunofluorescence. In the present case, we believe that the patient had SLE and developed an idiopathic disease of the minimal change disease-FSGS spectrum. -

Diagnosis and Management of Pyelonephritis

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF PYELONEPHRITIS ROBERT D. TAYLOR, M.D. Research Division F the four common nephropathies, glomerulonephritis, nephrosclerosis, Ointercapillary glomerulosclerosis and pyelonephritis, at present only pyelonephritis, the most familiar of these, offers the possibility of arrest or cure. It has been strangely neglected, possibly because it is a nosologic step- child, half surgical and half medical. Volhard and Fahr in 19141 did not list it among medical diseases of the kidney nor did Addis in 1925.2 Apart from the pediatric, obstetric and urologic aspects, little of general interest was written about it until 1939 when Weiss and Parker3 explored its relationship to hyper- icnsive disease. In 1948 Raaschau4 of Copenhagen published an excellent monograph on the subject with extensive pathologic and clinical studies. His most striking observation concerns its incidence. Among 3607 routine autop- sies he found histopathologic evidence of pyelonephritis in 5.6 per cent. One half of these persons had died of renal failure but in only 1 out of 6 was the condition recognized ante mortem. Undoubtedly, if a disease is both common and remediable, its diagnosis and treatment are of general interest. Etiology and Pathology The most common organisms in pyelonephritis are colon bacilli and hemo- lytic streptococci. In some cases the infection is secondary to lesions which prevent free urinary drainage. In this group surgical correction of the causes of urinary stasis usually permits eradication of infection. Among the remaining patients the process is primary with no demonstrable anatomic abnormality. The organisms apparently reach the kidney substance through the blood stream. The pelvis and lower urinary tract become involved by contamination with infected urine. -

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

some = Focal sections of = Segmental Focal Segmental kidney filters = Glomerulo FSGS Glomerulosclerosis = { are scarred Sclerosis How can research help? Research, which often requires patient participation, can lead to a better understanding of the causes, provide better diagnoses and more effective treatments, and ultimately help to find a cure. Be part of the discovery: By studying patients, researchers can more quickly unlock the mysteries of this disease. To get involved in research and stay informed, go to: Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network www.Nephrotic-Syndrome- NEPTUNE is a part of the NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). Funding and/or programmatic support for this project has been provided by U54 Studies.org DK083912 from the NIDDK and the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), the NephCure Foundation and the University of Michigan. The views expressed in written materials of publications do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the or call 1-866-NephCure Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. What is Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis? Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment Each person has Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a Your nephrologist may also recommend: two kidneys in rare disease that attacks the kidney’s filtering system • Diuretics and low salt diet help to control edema their lower back. (glomeruli) causing scarring of the filter. FSGS • A medication that blocks a hormone system called is one of the causes of a condition known as the renin angiotensin system (ACE inhibitor or ARB) Nephrotic Syndrome (NS). -

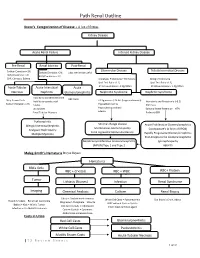

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium -

FSGS Fact Sheet 4.12.18

® Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a rare kidney disease characterized by dysfunction in the part of the kidney that filters blood (glomeruli). Only some glomeruli are aected, but continued damage can lead to kidney failure. Focal = Some Segmental = Sections Glomerulo = of the Filtering Units Sclerosis = Are Scarred FSGS Symptoms The exact cause of primary Early symptoms of FSGS are the same as Nephrotic Syndrome. FSGS is unknown and not precisely understood. However, genetic and Common Symptoms: environmental factors may be associated - Protein in the urine, which can be foamy (called with the disease. proteinuria) - Low levels of protein in the blood With FSGS, many individuals - Swelling in parts of the body, most noticeably around experience cycles the eyes, hands, feet, and abdomen (called edema) of remission and relapse. - Weight gain due to extra fluid building up in your body Remission means there - Can cause high blood pressure (called hypertension) is currently no and high fat levels in the blood (high cholesterol) protein spilling into the 50% of urine. patients with FSGS will Fast Facts progress to kidney failure. The only way to dierentiate FSGS from other primary Every FSGS Nephrotic Syndrome conditions is to have a kidney biopsy. patient follows a unique journey. FSGS in Adults FSGS in Children - FSGS occurs more - Focal Segmental frequently in adults than Glomerulosclerosis is one of in children and is most the leading causes of End Some patients prevalent in adults 45 Stage Renal Disease receive a kidney years or older. (ESRD) in children. transplant to treat their kidney failure due to FSGS, - African Americans are 5 - FSGS is associated with but FSGS comes back times more likely to get up to 20% of all new cases to attack the new FSGS in comparison with of Nephrotic Syndrome kidney 30-50% the general population. -

Renal Manifestations of Common Variable Immunodeficiency Tiffany

Kidney360 Publish Ahead of Print, published on April 21, 2020 as doi:10.34067/KID.0000432020 Renal Manifestations of Common Variable Immunodeficiency Tiffany N. Caza1, Samar I. Hassen1, Christopher Larsen1 1 Arkana Laboratories, Bryant, Arkansas Correspondence Dr. Tiffany N. Caza Arkana Laboratories 10810 Executive Center Drive Bryant, Arkansas 72022 United States [email protected] Copyright 2020 by American Society of Nephrology. ABSTRACT Background: Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is one of the most common primary immunodeficiency syndromes, affecting 1/25,000-50,000. Renal insufficiency occurs in approximately 2 percent of CVID patients. To date, there are no case series of renal biopsies from CVID patients, making it difficult to determine whether individual cases of renal disease in CVID represent sporadic events or are related to the underlying pathophysiology. We performed a retrospective analysis of renal biopsies in our database from patients with a clinical history of CVID (n=22 patients, 27 biopsies). Methods: Light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy were reviewed. IgG subclasses, PLA2R immunohistochemistry, and THSD7A, EXT1, and NELL1 immunofluorescence were performed on all membranous glomerulopathy cases. Results: Acute kidney injury and proteinuria were the leading indications for renal biopsy in CVID patients. Immune complex glomerulopathy was present in 12 of 22 (54.5%) cases including 9 with membranous glomerulopathy, one case with a C3 glomerulopathy, and one case with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with IgG3 kappa deposits. All membranous glomerulopathy cases were PLA2R, THSD7A, EXT1, and NELL1 negative. The second most common renal biopsy diagnosis was chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, affecting 33% cases. All tubulointerstitial nephritis cases showed tubulitis and a lymphocytic infiltrate with >90% CD3+ T cells. -

Idiopathic Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

Idiopathic Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) This leaflet explains what FSGS is and how it is treated. What is FSGS Your kidney biopsy has shown that your fluid retention, leading to tissue swelling and protein leak (nephrotic syndrome), is caused by a condition called ‘Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis’ (FSGS). This means that there is damage and scarring to the kidney. In most cases, little is known about the actual cause of the damage, but it appears that in some patients, a substance in your own circulation attacks the kidneys. While the symptoms of the nephrotic syndrome may be unpleasant, the main worry with this condition is that it damages kidney function in the longer term. There is a 50% risk of renal failure after five years, and this rises with the amount of proteinuria (protein leak) in your urine. It is also a condition that is likely to recur after a kidney transplant. What is the treatment for FSGS? There is a treatment that has been shown to cure about one third of people with FSGS. If the treatment works, the risk of future kidney failure is very small. If the treatment does not work, then the 50% risk of kidney failure remains. Initial treatment The treatment, which we offer at this hospital, is one that is quite intensive for six months and may have side effects. This needs to be balanced against the risk of kidney failure without treatment. Prednisolone 1mg/kg of body weight (max 80mg) daily minimum 4-6 months Lansoprazole 30mg daily Alendronate 70mg weekly Nystatin 1ml four times a day Septrin 480mg daily + Nephrotic syndrome treatment if appropriate You may have a monthly outpatient clinic appointment with a blood test for kidney function, cholesterol, full blood count (to check your white blood cells) and urine test (24 hour urine collection for protein and clearance), which will show how much protein is leaking from your kidneys and how well they are working. -

Karyomegalic Interstitial Nephritis with Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: a Rare Association

Case Report Karyomegalic interstitial nephritis with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A rare association S. Radha, A. Tameem, B. S. Rao1 Department of Anatomical Pathology and Cytology, Aware Global Hospitals, L.B. Nagar, 1Consultant Nephorologist, Matrix Hospitals, Ramanthapur, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Karyomegalic interstitial nephritis (KIN) is a rare form of, progressive chronic interstitial nephritis. We present a case of KIN in a child, who was also found to have nephrotic syndrome because of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis on renal biopsy. To our knowledge, this is the first case of KIN associated with glomerulopathy. Key words: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, interstitial nephritis, karyomegaly, nephrotic syndrome Introduction facial puffiness and edema of one year duration. He was diagnosed to have nephrotic syndrome and was treated Karyomegalic interstitial nephritis (KIN) was first described by a local physician with steroids. He did not improve, in 1974.[1] A detailed description of patients with history of however, and was referred to this hospital for further recurrent respiratory infections and progressive renal failure management. was given 1979.[2] The prevalence of this disease is less than 1%.[3] The pathogenesis of KIN is unclear. The disease There was no family history of kidney disease. He is has no known treatment. The case under discussion has the first child of non-consanguineous marriage. There various rare features like young age of the patient, associated was no history of drug ingestion including exposure glomerulopathy causing nephrotic syndrome and normal to mycotoxins or other herbal medicines. No history of renal function, which is showing gradual deterioration. recurrent respiratory symptoms. On examination, patient Normal renal function at the time of diagnosis is known and had stunted growth with moon facies, secondary to in one large series published by Bhandari et al., one out of steroids and had clinical features of rickets. -

Emphysematous Pyelonephritis Clinicoradiological Classification, Management, Prognosis, and Pathogenesis

ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Emphysematous Pyelonephritis Clinicoradiological Classification, Management, Prognosis, and Pathogenesis Jeng-Jong Huang, MD; Chin-Chung Tseng, MD Background: Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is tients who received antibiotic treatment alone was 40% (2 a rare, severe gas-forming infection of renal paren- of 5 patients). The success rate of management by percu- chyma and its surrounding areas. The radiological clas- taneous catheter drainage (PCD) combined with antibi- sification and adequate therapeutic regimen are contro- otic treatment was 66% (27 of 41 patients). In classes 1 and versial and the prognostic factors and pathogenesis remain 2 EPN, all the patients who were treated using a PCD or uncertain. ureteral catheter combined with antibiotic treatment sur- vived. In extensive EPN (classes 3 and 4), 17 (85%) of the Objectives: To elucidate the clinical features, radio- 20 patients with fewer than 2 risk factors (ie, thrombocy- logical classification, and prognostic factors of EPN; to topenia, acute renal function impairment, disturbance of compare the modalities of management (ie, antibiotic consciousness, or shock) were successfully treated using treatment alone, percutaneous catheter drainage com- PCD combined with antibiotic treatment; and the pa- bined with antibiotic treatment, or nephrectomy) and out- tients with 2 or more risk factors had a significantly higher come among the various radiological classes of EPN; and failure rate than those with no or only 1 risk factors (92% to clarify the gas-forming mechanism and pathogenesis vs 15%, PϽ.001). Eight of the 14 patients who had an un- of EPN by gas analysis and pathological findings. successful treatment using a PCD underwent subsequent nephrectomy, 7 of whom survived. -

Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

Form: D-8805 Glomerulonephritis Series Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) What is Focal and Segmental Glomerulonephritis (FSGS)? FSGS is a disease of the filters of the kidney. Your kidneys have 1 million filters that clean toxins (harmful substances) from your blood. These filters, called glomeruli, also prevent cells and protein from spilling out from your blood into the urine. FSGS is a type of glomerulonephritis (GN), an inflammation in the filters in your kidneys. This is a rare condition that affects your kidney and overall health. How is FSGS diagnosed? A kidney biopsy is used to diagnose FSGS. This means a small sample of tissue is taken from your kidney. There are different types of GN. Your doctor will use a microscope to look at the patterns in your biopsy sample to determine the type you have. FSGS has its name because of the pattern that doctors see when looking at a kidney biopsy sample. Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis literally means “partial scarring in some areas of the filters of the kidneys”. What causes FSGS? FSGS can happen for many reasons. This may include high blood pressure (hypertension), diabetes, having only one kidney, or having small blood vessels in your kidney. The condition can develop quickly without any known trigger. Sometimes, infections or medications may cause FSGS, but this is rare. Some genetic conditions may also cause the condition, but most often it does not run in families. Your doctor may do tests to see if you have any other conditions for your FSGS. Often, we aren’t able to find out what the cause is. -

Does Pre-Eclampsia Predispose Patients to the Development Of

Lioufas et al. J Clin Nephrol Ren Care 2016, 2:012 Volume 2 | Issue 2 Journal of Clinical Nephrology and Renal Care Case Series: Open Access Does Pre-Eclampsia Predispose Patients to the Development of Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis? “The Chicken or the Egg?” Nicole Lioufas1, Jonathan Ling1, Juli Jaw2, Mathew Mathew2, Matthew Jose1 and Richard Yu1* 1Department of Nephrology, Royal Hobart Hospital, Australia 2Department of Nephrology, Launceston General Hospital, Australia *Corresponding author: Yu Richard, Department of Nephrology, Royal Hobart Hospital, Australia, E-mail: [email protected] well described in the literature- characterized histologically by Abstract endotheliosis and podocyte swelling [3]. Pre-eclampsia is the most common medical complication of pregnancy affecting 3-5% of pregnancies worldwide. Traditional Traditional teaching has generally maintained that the natural teaching has generally maintained that the natural history of Pre- history of Pre-eclampsia is one of resolution of renal pathology eclampsia is one of resolution of renal pathology and other clinical and other clinical features- some days to weeks after delivery of the features- some days to weeks after delivery of the placenta. placenta. Renal injury is mediated by both endothelial and podocyte Renal injury is mediated by both endothelial and podocyte injury injury in pre-eclampsia. In some women however, the renal injury in pre-eclampsia. In some women however, the renal injury does does not resolve and proteinuria persists following pregnancy. The not resolve and proteinuria persists following pregnancy. The development of further glomerular lesions, notably focal segmental development of further glomerular lesions, notably focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) following pre-eclampsia, has previously glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) following pre-eclampsia, has previously been described, and is an association that is increasingly been described [4].