The Coloration and Glazing of the Teas of Commerce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemometrics Methods Applied to Non-Selective Signals in Order to Address Mainly Food, Industrial and Environmental Problems

ber 2019 Decem Chemometrics Methods Applied to Non-Selective Signals in Order to Address Mainly Food, Industrial and Environmental Problems PhD Thesis Maryam Hooshyari University of Genova Doctorate in Sciences and Technologies of Chemistry and Materials Chemometrics Methods Applied to Non-Selective Signals in Order to Address Mainly Food, Industrial and Environmental Problems PhD Thesis Curriculum: SAFC XXXII Cycle Maryam Hooshyari Supervisor: Prof. Monica Casale 1 Data Sheet Title: Chemometrics Methods Applied to Non-Selective Signals in Order to Address Mainly Food, Industrial and Environmental Problems Subtitle: PhD thesis Author: Maryam Hooshyari Supervisor: Prof. Monica Casale Department: Pharmaceutical, Food and Cosmetology Sciences, Research Group of Analytical Chemistry and Chemometrics Curriculum: Pharmaceutical, Food and Cosmetology Sciences (SAFC) University: Università degli Studi di Genova Financial support: Università degli Studi di Genova Thesis Abstract: Chemometrics is a chemical discipline that uses mathematical and statistical methods in order to extract useful information from multivariate chemical data. Moreover, chemometrics is applied to correlate quality parameters or physical properties to analytical instrument data such as calculating pH from a measurement of hydrogen ion activity or a Fourier transform interpolation of a spectrum. Aim of this thesis project is to develop chemometrical strategies for the elaboration and the interpretation of non-selective complex data in order to solve real problems in food, industry and environmental fields. Keywords: Chemometrics, PCA, PARAFAC, SIMCA, PLS-CM, PLS- DA, ANOVA, PLS, QDA, D-Optimal Design, Green Tea, Lichen Thalli, Air Pollution, Engine Oil, Base Oil, Crude Oil, Naphthenic Acid, Produced Water, NIR, Fluorescence, LC- HRMS, UV-Visible, Spectroscopy, Chromatography. 2 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................... -

Mimi's Tranquili-Tea

Mimi’s Teas ~ A Loose Leaf Tea Shoppe Menu of Tea ~Black Tea~ Apple Spice Premium Ceylon Black Tea with Apple Bits, Cinnamon Pieces, and Cloves $3.15/oz Apricot Black Tea Premium Black Tea Blend & Flavors $3.15/oz Banana Sundae China Black Tea, Milk Chocolate Drops, Banana Chips, Flavor $3.15/oz Black Currant Premium Ceylon Black Tea, With Natural Black Currant Flavor $3.25/oz Black Velvet Organic China Black Tea, Ginseng, Peppermint, & Licorice $4.75/oz 1 Mimi’s Teas ~ A Loose Leaf Tea Shoppe Menu of Tea Buddha’s Delight Tea Premium Black Tea with Apple its, Orange Peel, Currants, Cinnamon, Almond Flakes, Cloves, and Safflowers $4.35/oz Cha Cha Chai Organic Indian Black Tea Blend Organic Ginger, Organic Cinnamon, Organic Cardamom, Organic Clove & Organic Pepper $4.15/oz Cherry India Black Tea, Safflowers, Cherries, & Cherry Flavor $2.95/oz Cherry Cordial Black Tea, Cherry, & Chocolate Bits ~natural & artificial flavor~ $3.15/oz Chocolate Almond Black Tea, Almond, Cocoa Beans ~artificial flavor~ $3.15/oz Chocolate Supreme Black Tea, Chocolate Bits, Natural & Artificial Flavor ~contains soy~ $3.55/oz 2 Mimi’s Teas ~ A Loose Leaf Tea Shoppe Menu of Tea Coconut Heaven Naturally Flavored Premium Black Tea, & Shredded Coconut $3.35/oz Earl Grey Manhattan Blend Vintage British Black Tea Blend with Bergamot & Flowers $3.95/oz Earl Grey Special Blend Premium Ceylon Black Tea with Bergamot & Vanilla $3.45/oz Decaf Earl Grey Naturally Decaffeinated Natural Bergamot Flavored Black Tea $4.95/oz Ginger Peach Premium Ceylon Black Tea Flavored with -

Frida Kahlo Inspired Afternoon Tea

“It is not worthwhile to leave this world without having had a little fun in life” Frida Kahlo Frida Kahlo Inspired Afternoon Tea Inspired by the opening of the most talked about exhibition of the year, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the new afternoon tea by The Lanesborough’s Head Pastry Chef Gabriel Le Quang celebrates the colours, shapes and textures of the life of Mexican artist, Frida Kahlo. Tea commences with a taste of Agua de Jamaica, the classic Mexican water flavoured with hibiscus typically drank in the Mexican merienda (afternoon tea period). Alongside traditional scones and accompaniments, and some classic afternoon tea sandwiches, the pastry selection has been inspired by the life of Frida: Corn sablé with dulce de leche, combining the Mexican tastes of corn and the traditional dulce de leche Margarita Baba, a classic baba with a Margarita twist using agave and tequila Carrot Cake, decorated in Frida-esque style Passion Fruit and Raspberry Éclair, inspired by the work of Frida with Central American flavours Mexican Chocolate Tartelette, made with Mexican chocolate and garnished with delicate sugar flowers For the full merienda experience, guests can order hot chocolate or Mexican spiced hot chocolate instead of tea or coffee with their Afternoon Tea. FRIDA KAHLO INSPIRED AFTERNOON TEA A selection of finger sandwiches Egg and Watercress, Cucumber and Mint Smoked Salmon and Cream Cheese, Chicken Tinga, Traditional Guacamole Selection of Frida pastries Homemade scones, fruit preserves, and -

The Journey of a Tea Merchant

Summer, 2018 Upton Tea Quarterly Page 1 Vol 27 No. 3 Holliston, Massachusetts Summer, 2018 THE JOURNEY OF A TEA MERCHANT ith a lifelong passion for the world’s finest teas, Roy Fong, owner of the Imperial Tea Court in San Francisco, has been importing premium tea to the United States for more than thirty years. WHe has journeyed to China countless times in the pursuit of happiness to be found in a cup of tea. “Tea chose me. Looking back, there was no other path but tea.” I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with him at the Imperial Tea Court. Over many cups of tea, he shared his story. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 51. ' (800) 234-8327 www.uptontea.com Copyright© 2018 2018 Upton Upton Tea Tea Imports. Imports. All rights All rights reserved. reserved. PagePage 2 2 UptonUpton Tea Tea Quarterly Quarterly Summer,Summer, 2018 2018 Summer,Summer, 2018 2018 UptonUpton Tea Tea Quarterly Quarterly PagePage 3 3 NOTEWORTHY...NOTEWORTHY... TABLETABLE OF OF CONTENTS CONTENTS MayMay 12, 12, 2018 2018 OverOver twenty twenty new new teas teas have have been been introduced introduced AA Note Note to to our our Valued Valued Customers Customers ................................. .................................3 3 inin this this issue issue of of our our newsletter newsletter, including, including spring- spring- CurrentCurrent Tea Tea Offerings Offerings AA Note Note to to our our Valued Valued Customers: Customers: harvestharvest first first flush flush Darjeelings Darjeelings (page (page 9) 9) and and a afirst first AfricaAfrica..............................................................................................................................................3131 -

Shandong Color of the Tea and to Get the Best Avor

Encyclopedia of Chinese and Taiwanese Tea Chinese name Tea Category Elevation (meters) As the second most widely consumed beverage, second only to water, tea has a lot Classification of Tea Aroma level Xueqing tea 雪青茶 Laoshan Green tea崂山绿茶 Taste level more varieties than you would think. Like wine where the taste and smell of the nal 600 product is determined by the terroir, the soil and the elevation of the plantation White tea Yellow tea Green tea Oolong tea Black tea Dark (Pu-erh) tea Thick Long Bold determines the unique characteristics specic to that tea. In fact, all of the world’s tea 白茶 黄茶 绿茶 乌龙茶 红茶 黑茶 Mellow Sweet (about , types) is produced from one species of the tea tree, the Camellia sinensis. 500 The two major varietals within this specie is the China bush (Camellia sinensis var. 0 < 8 12 - 80 100 Fresh Brief Brisk sinensis) and Assam bush (Camellia sinensis var. assamica). The China bush is grown PERCENTAGE OF FERMENTATION (%) SCENT DURATION RAW 400 throughout China, Taiwan and Japan. FERMENTED China, the origin of the tea plant and the world’s top tea producing country, grows 1 Elevation 75 80 85 < 95 range of more than types of tea. Depending on the location of the bush, the terrior, the 300 leaves tenderness and size, time of harvest, and its production method (amount of PREFERED WATER TEMPERATURE (°C) plantation Prefrecture fermentation), the resulting leaves develop its own distinct shape, color, aroma and Glass Purple Clay 1 1 taste that cannot be be produced elsewhere. The fermentation process, or the 200 Porcelain lack-thereof, determines the type of tea: White, Yellow, Green, Oolong, Black, RECOMMENDED TEA-WARE and Dark. -

Tea Selection

Tea Selection White Tea Bluebells Raspberry with Leaves Decaffeinated Tea White teas are the delicate tips or A delightful blend of lilac, citrus Juicy raspberry tea Apricot with Flowers and berries buds of the tea plant Russian Caravan Apricot with marigolds Blueberry Smokey and exotic Carnival Ride Ceylon Flavorful fresh blueberries Snowflake Scented with refreshing Full bodied decaf Caribbean Strawberry Coconut and almond blend pineapple Earl Grey Sweet strawberries and creamy Tibetan Tiger Pai Mu Tan coconut Oil of bergamot blend (China) Superior white tea Perfect balance of caramel & nut Chai Americaine English Breakfast Vanilla Pom Pom For the western palate filled with Decaf British blend Oolong Pomegranate and Madagascar spices Vanilla with Pieces Oolong teas are 10% - 75% vanilla Chocolate Almond Creamy vanilla decaf oxidized which varies their range in An almond cookie dipped in taste between green tea & black tea Green Tea chocolate Green teas are steamed or cooked to Herbal/Tisane Camden Station Chocolate Cherry retain their color Herbals/Tisane are not made from Oolong blended with orange and Like a chocolate dipped cherry tea but contain only herbs, fruit, Dragonwell Green caramel Chocolate Mint Kiss spices and essential oils. They are (China) a sophisticated flat leaf Georgia Peach Mint and chocolate, a superb naturally caffeine free. Sencha Smokey oolong paired with blend Gunpowder: Caramel Cream luscious peach Chocolate Strawberry Rooibos with creamy caramel Ti Kuan Yin Chocolate covered strawberries in “Temple of Heaven” -

Green and White Teas

GREEN AND WHITE TEAS Gunpowder Temple Lü Mao Hou of Heaven „Green –haired Monkey“ is a Gunpowder“. A good sort famous Chinese green tea of this kind of tea. Tiny, from Fu-ťijen province. dark green, shiny leaf, The leaf is spiral-rolled, rolled into a pearl shape. A richly haired and has a balanced infusion with a clear green color. The slight flowery-sweet, infusion is light green with pleasantly bitter-fresh a nutty, flowery aroma taste. and a soft sweet taste. Teapot (1 infusion) 68 CZK Zhong 68 CZK Teapot (3 infusions) 98 CZK Luan Gua Pian Bai Mao Hou „Melon seeds“ hails from „White-haired Monkey“ is a the An-chuej province, famous Chinese green tea and has been popular from Fu-ťijen province. since the age of the Ming The curlier leaves of this dynasty, became known as grey-green tea are richly „Emperor’s tea“ during haired, while its taste is the Qing dynasty. Its full of gentle flowery infusion is a dark green tones, with a sweetly color with an emerald aromatic infusion. shine and a clean, sweet taste. Zhong 68 CZK Teapot (3 infusions) 98 CZK Zhong 68 CZK Teapot (3 infusions) 98 CZK 2 Lu Xue Ya Tian Mu Long Zhu Cha „Green Snow“. Tiny, carefully longrolled leaves „Dragon Eyes“. A hyper- have an emerald color and fine high–quality green tea the bright aroma of green from select fresh tea shoots tea. The tea is prepared harvested on the border of using steam (similar to the Zhe-jiang and Anhui Japanese Sencha teas), provinces. -

Tea Sector Report

TEA SECTOR REPORT Common borders. Common solutions. 1 DISCLAIMER The document has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under Joint Operational Programme Black Sea Basin 2014-2020. Its content is the sole responsibility of Authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Common borders. Common solutions. 2 Contents 1. Executıve Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Tea Sector Report ............................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1. Current Status ............................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1. World .................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.2. Black Sea Basin ................................................................................................................................... 49 1.1.3. National and Regional ........................................................................................................................ 60 1.2. Traditional Tea Agriculture and Management ............................................................................................ 80 1.2.1. Current Status ................................................................................................................................... -

Nikaido Tea List

NIKAIDO TEA LIST Our eponymous line of Nikaido Tea are made in Richmond, BC and sourced from the finest tea estates and companies worldwide--which results in a beverage that tastes and good as it smells! We also carry other reputable brands of tea such as Kusmi, Tea Forte, Wedgwood, Republic of Tea and Flying Bird Botanicals. 150-3580 Moncton Street Richmond, BC V7E 3A4 Tel 604.275.0262 Prices are Canadian dollars (CAD) and subject to change without notice Page 1 of 6 Green Unflavored Origin: Japan NAME TASTE/CHARACTER WEIGHT PRICE Bancha Summer harvest-Shizouka 80g $10.95 Fukamushi Deep-steamed Shizouka sencha. A green, sweet taste. 100g $15.95 Fukamushi *16 Teabags Fukamushi in convenient large 2-cup teabags *16 Teabags $10.95 Genmaicha Bancha blended with toasted rice 80g $11.95 Genmaicha Extra Toasted rice, summer harvest tea from Shizouka with Matcha 80g $14.95 Hojicha Roasted Bancha. Low in caffeine. 50g $9.95 Kukicha Green tea comprised of the twigs and vein of leaf. 80g $14.95 Sencha uji Spring harvest green tea from Uji 100g $14.95 Green Flavored NAME TASTE/CHARACTER WEIGHT PRICE Bangkok Coconut and lemongrass taste 70g $10.95 Biscotti Walnut with cookie taste 80g $10.95 Earl Green (Organic) Earl grey taste in Taiwanese Pouchong tea base. 70g $11.95 Haiku Vanilla strawberry peach 70g $10.95 Jasmine Pearls Tiny jasmine-scented hand-rolled leaves resembling a pearl. 80g $14.95 Moroccan Mint Spearmint and peppermint in Chinese gunpowder tea base 80g $10.95 Organic Jasmine (Organic) Jasmine scented 100g $11.95 Passionfruit Full-flavored -

Gunpowder Green Free Download

GUNPOWDER GREEN FREE DOWNLOAD Laura Childs | 256 pages | 25 Sep 2006 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780425184059 | English | New York, United States Té Verde China Gunpowder For example, famous Moroccan mint tea is made with Gunpowder tea and fresh mint. Find our latest updates here. All you need is a small saucepan, bicarbonate of soda Gunpowder Green some spices optional. Rolling renders the leaves less susceptible to physical damage and breakage and allows them to retain more of their flavor and aroma. Junshan Yinzhen Huoshan Huangya. Retrieved International Delivery to over 50 countries See our latest store updates. For example, Moroccan Mint tea would never had such a refreshing and unique flavor without gunpowder tea. Earl Grey Collection. Code: MSTR Measure about grams of tea leaves per cup of water. Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, Gunpowder Green was likely to have been a classic Chinese "gunpowder" tea, fired in large drums for a smoky taste and tightly rolled to resemble pellets of gunpowder. For the first and second brewing, leaves should be steeped for around Gunpowder Green minute. Collections Caffeine In Coffee. As Gunpowder Green example AAA is considered the highest grade while is a relatively lower grade. Gunpowder is perfect for making Pink Milk tea. Numerology NO. Our Top 5 Coffees. Coffee Equipment. Make sure to boil the tea leaves for at least minutes and add very cold water later. The origins of tea lie in China: legend has it that it was discovered when a few leaves fell into the mythical emperor Shennong's cup of hot water. -

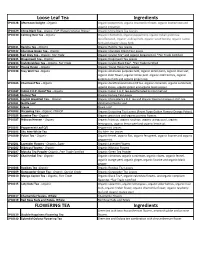

Ingredients Ingredients Loose Leaf Tea FLOWERING

Loose Leaf Tea Ingredients SP10128 Afternoon Delight - Organic Organic peppermint, organic chamomile flower, organic licorice root and organic cinnamon. SP10129 China Black Tea - Organic FOP (Flowery Orange Pekoe) Organic China Black Tea Leaves SP10130 Calming Rest Tea - Organic Organic chamomile, organic peppermint, organic Indian green tea decaffeinated, organic scullcap herb, organic wood betony, organic catnip herb and organic stevia herb. SP10131 Bancha Tea - Organic Organic Bancha Tea Leaves SP10132 Chunmee Green Tea - Organic Organic Chunmee Green Tea Leaves SP10134 Earl Grey Tea - Organic, Fair Trade Organic Ceylon Tea* and organic bergamot oil. *Fair Trade Certified SP10135 Dragonwell Tea - Organic Organic Dragonwell Tea Leaves SP10136 Irish Breakfast Tea - Organic, Fair Trade Organic Ceylon Black Tea*. *Fair Trade Certified SP10137 Young Hyson - Organic Organic Young Hyson Tea Leaves SP10138 Stay Well Tea -Organic Organic echinacea purpurea herb, organic lemon balm, organic olive leaf, organic elder flower, organic lemon peel, organic elder berries, organic goldenseal herb and organic ginger root. SP10166 Chai Decaf Tea - Organic Organic decaffeinated India FOP tea, organic cinnamon, organic cardamom, organic cloves, organic ginger and organic black pepper SP10167 Indian F.O.P. Decaf Tea - Organic Organic Indian F.O.P. tea decaffeinated by CO2 method SP10168 Oolong Tea Organic Oolong Tea Leaves SP10185 English Breakfast Tea - Organic Organic China Black F.O.P. tea and Organic Keemun Congou F.O.P. tea SP10181 Nettle Leaf Wildcrafted Nettle Leaf SP10182 Stevia Stevia Leaf SP10183 Darjeeling Tea - Organic, FTGFOP Organic Darjeeling Tea Leaves (Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe) SP10186 Jasmine Tea - Organic Organic green tea and organic jasmine flowers. -

Herbal/Tisane Scented Black Tea Green Tea Scented Green Tea Decaffeinated Tea White Tea Oolong Puerh Black Tea Scented Black Te

White Tea Scented Black Tea Green Tea Herbal/Tisane White teas are the delicate tips or Chocolate Cherry Green teas are steamed or cooked Herbals/Tisane are not made from buds of the tea plant Cherry and chocolate to retain their color tea but contain only herbs, fruit, spices and essential oils. They are Carnival Ride Chocolate Mint Kiss Dragonwell Green naturally caffeine free. Scented with pineapple Mint and chocolate (China) a sophisticated flat Pai Mu Tan Chocolate Strawberry leaf Sencha Blueberry Muffin (China) Superior white tea Chocolate and strawberries Genmaicha with Toasted Rice Rooibos with blueberry Coco Mocho (Japan) Sencha blended with Caramel Cream Oolong Chocolate and malt is puffed rice Rooibos with caramel Oolong teas are 10% - 75% sensational, try it “au lait” Gunpowder: Temple of Heaven Chocolate Minterland oxidized which varies their range Coconut Cream (Japan) delightful taste Rooibos with cool mint and in taste between green tea Coconut and chocolate Sencha Fukujyu Pan Fired chocolate and black teas Countess Grey (Japan) clear sparkling flavor Creamsicle Camden Station Earl Grey with orange Rooibos orange and cream Oolong blended with orange and spice Scented Green Tea Degas and caramel Cupid’s Arrow Scented green teas are made from Herbal with apples, rose hips, Georgia Peach Cherry, almond, and vanilla blending a green tea with an herb, hibiscus, carrots, blueberries Della Robbia essential oil, or fruit. and vanilla Smokey oolong with peach Ti Kuan Yin Apple, pear, plum, orange Au Pear Enchanted April (China)