209 Fur Traders, Racial Categories, and Kinship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premontre High School, Dec. No. 26762-A, 26763-A

STATE OF WISCONSIN BEFORE THE WISCONSIN EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS COMMISSION - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - : PREMONTRE EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, an : unincorporated association, : : Complainant, : : vs. : Case 12 : No. 44069 Ce-2102 THE PREMONSTRATENSIAN ORDER, a : Decision No. 26762-A religious organization, THE : PREMONSTRATENSIAN FATHERS, INC., : a Wisconsin corporation, PREMONTRE : HIGH SCHOOL, INC., a Wisconsin : corporation & NOTRE DAME de la BAIE, : INC., a Wisconsin corporation, : : Respondents. : : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - : : PREMONTRE EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, an : unincorporated association, and : EUGENE A. LUNDERGAN, DONALD C. : BETTINE, and JOHN J. JAUQUET, : officers of the PREMONTRE EDUCATION : ASSOCIATION, : : Complainants, : Case 13 : No. 44097 Ce-2103 vs. : Decision No. 26763-A : THE PREMONSTRATENSIAN ORDER, a : religious organization, THE : PREMONSTRATENSIAN FATHERS, INC., : a Wisconsin corporation, PREMONTRE : HIGH SCHOOL, INC., a Wisconsin : corporation & NOTRE DAME de la BAIE, : INC., a Wisconsin corporation, : : Respondents. : : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Appearances: Mr. Thomas J. Parins, Attorney at Law, Jefferson Court Building, 125 South Jefferson Street, P.O. Box 1038, Green Bay, Wisconsin 54305, appearing on behalf of Premontre Education Association and, for purposes of the motions posed here, for Eugene A. Lundergan, Donald C. Bettine, and John J. Jauquet. Mr. Herbert C. Liebmann III, with Mr. Donald L. Romundson on the brief, Liebmann, Conway, Olejniczak & Jerry, S.C., Attorneys at Law, 231 South Adams Street, P.O. Box 1241, Green Bay, Wisconsin 54305, appearing on behalf of the Premonstratensian Order and the Premonstratensian Fathers. Mr. Dennis W. Rader, Godfrey & Kahn, S.C., Attorneys at Law, 333 Main Street, Suite 600, P.O. Box 13067, Green Bay, Wisconsin 54307-3067, appearing on behalf of Notre Dame de la Baie Academy, Inc. Mr. Mark A. Warpinski, Warpinski & Vande Castle, S.C., Attorneys at Law, 303 South Jefferson Street, P.O. -

The Beaver Club (1785-1827): Behind Closed Doors Bella Silverman

The Beaver Club (1785-1827): Behind Closed Doors Bella Silverman Montreal’s infamous Beaver Club (1785-1827) was a social group that brought together retired merchants and acted as a platform where young fur traders could enter Montreal’s bourgeois society.1 The rules and social values governing the club reveal the violent, racist, and misogynistic underpinnings of the group; its membership was exclusively white and male, and the club admitted members who participated in morally grotesque and violent activities, such as murder and slavery. Further, the club’s mandate encouraged the systematic “othering” of those believed to be “savage” and unlike themselves.2 Indeed, the Beaver Club’s exploitive, exclusive, and violent character was cultivated in private gatherings held at its Beaver Hall Hill mansion.3 (fig. 1) Subjected to specific rules and regulations, the club allowed members to collude economically, often through their participation in the institution of slavery, and idealize the strength of white men who wintered in the North American interior or “Indian Country.”4 Up until 1821, Montreal was a mercantile city which relied upon the fur trade and international import-exports as its economic engine.5 Following the British Conquest of New France in 1759, the fur trading merchants’ influence was especially strong.6 Increasing affluence and opportunities for leisure led to the establishment of social organizations, the Beaver Club being one among many.7 The Beaver Club was founded in 1785 by the same group of men who founded the North West Company (NWC), a fur trading organization established in 1775. 9 Some of the company’s founding partners were James McGill, the Frobisher brothers, and later, Alexander Henry.10 These men were also some of the Beaver Club’s original members.11 (figs. -

The Fur Trade and Early Capitalist Development in British Columbia

THE FUR TRADE AND EARLY CAPITALIST DEVELOPMENT IN BRITISH COLUMBIA RENNIE WARBURTON, Department of Sociology, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, V8W 2Y2. and STEPHEN SCOTT, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1S 5B6. ABSTRACT/RESUME Although characterized by unequal exchange, the impact of the fur trade on the aboriginal societies of what became British Columbia involved minimal dis- ruption because the indigenous modes of production were easily articulated with mercantile capitalism. It was the problems arising from competition and increasing costs of transportation that led the Hudson's Bay Company to begin commodity production in agriculture, fishing and lumbering, thereby initiating capitalist wage-labour relations and paving the way for the subsequent disast- rous decline in the well-being of Native peoples in the province. Bien que characterisé par un échange inégale, l'impact du commerce de fourrure sur les societiés aborigonaux sur ce qui est devenu la Colombie Britanique ne dérangèrent pas les societés, car les modes indigènes de production était facile- ment articulés avec un capitalisme mercantile. Ce sont les problèmes qui venaient de la competition et les frais de transportation qui augmentaient qui mena la Companie de la Baie d'Hudson à commencer la production de commodités dans les domaines de l'agriculture, la pêche et l'exploitement du bois. Par ce moyen elle initia des rapports de salaire-travail capitalist et prépara les voies pour aboutir å une reduction catastrophique du bien-être des natifs dans cette province. THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NATIVE STUDIES V, 1(1985):27-46 28 R E N N I E W A R B U R T O N / S T E P H E N S C O T T INTRODUCTION In the diverse cultures in British Columbia prior to and after contact with the Europeans, economic activity included subsistence hunting, fishing and gathering as well as domestic handicrafts. -

Nemaska Lithium and the Centre De Formation Professionnelle De La Baie-James Announce a New Training for the Future Whabouchi Mine Employees

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release NEMASKA LITHIUM AND THE CENTRE DE FORMATION PROFESSIONNELLE DE LA BAIE-JAMES ANNOUNCE A NEW TRAINING FOR THE FUTURE WHABOUCHI MINE EMPLOYEES CHIBOUGAMAU, QUÉBEC, November 7, 2018 — Nemaska Lithium and the Centre de formation professionnelle de la Baie-James are pleased to announce a new partnership that seals an agreement in relation to human resources training support and coordination activities for the Whabouchi project. As a result of the close collaboration between the Centre de formation professionnelle de la Baie- James, the Service aux entreprises et aux individus de la Baie-James and Nemaska Lithium, this agreement will enable the latter to benefit from the facilities, workshops and equipment needed for various trainings. “This partnership demonstrates our commitment to work with the communities that welcome and support us in the realization of our project”, commented Chantal Francoeur, Vice President, Human Resources and Organizational Development at Nemaska Lithium. “This is a perfect example of the potential of our collaborative approach between private businesses and educational institutions, and we are pleased to be able to count on the expertise and skills of the Centre de formation professionnelle de la Baie-James for the training of the future resources that will be at the heart of Nemaska Lithium’s success.” A unique project in the region Designed and implemented in less than eight months, this partnership will enable Nemaska Lithium to enroll more than 200 future employees in the training, for which all activities, including accommodation and meal logistics, will be coordinated by the Centre de formation professionnelle de la Baie-James. -

Profile 2005: Softwood Sawmills in the United States and Canada

Abstract Preface The softwood lumber industry in the United States and This report updates Profile 2003: Softwood Sawmills in the Canada consists of about 1,067 sawmills. In 2005 these United States and Canada, published April 2003. Profile sawmills had a combined capacity of 189 million m3 2005 contains updated information on location, ownership, (80 × 109 bf). In 2004, they employed about 99,000 people and approximate capacities of 1,067 softwood sawmills in and produced 172 million m3 (nominal) (73.0 × 109 bf) of the United States and Canada. Additionally, it presents data lumber. In the process, they consumed about 280 million m3 on employment, lumber recovery, and average log sizes in (9.9 × 109 ft3) of timber. Employee productivity was near the industry, along with an assessment of near-term prospec- 2,125 m3 (900,000 bf) per worker per year for dimension tive U.S. economic conditions. and stud mills but about half that for board, timber, and The information in this study was originally compiled from specialty mills. Average saw log size varied from 42 cm a variety of published sources. These included directories of (16.6 in.) in British Columbia to 16 cm (6.2 in.) in the bo- wood-using industries published by regional United States real region of eastern Canada. Average lumber recovery fac- and Canadian forestry departments, commercial directo- tors varied from 267 bf/m3 (7.55 bf/ft3) for timber mills to ries such as the Big Book (Random Lengths Publications, 236 bf/m3 (6.6 bf/ft3) for specialty mills. -

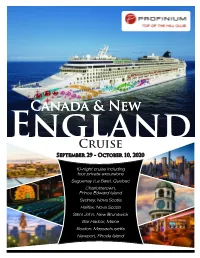

Brochure with Full Details Is Available

Canada & New EnglCruisande September 29 - October 10, 2020 10-night cruise including four private excursions Saguenay (La Baie), Quebec Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island Sydney, Nova Scotia Halifax, Nova Scotia Saint John, New Brunswick Bar Harbor, Maine Boston, Massachusetts Newport, Rhode Island Montreal, Quebec Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia DAY 1 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29 FLIGHT TO MONTREAL Today we will transfer to the airport for our flight to Montreal, Canada. Upon arrival, our group will get settled into the hotel and then spend the remainder of the day exploring this exciting city at our leisure. Montreal offers one of North America’s most exciting food scenes, with an amazing variety of food markets, English pubs, Jewish delis, quaint cafés, and more, making dinner on your own this evening a fun adventure! Note: The airport location and airline will be confirmed approximately 9 months before departure. DAY 2 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30 QUEBEC CITY, QUEBEC (BD) Following breakfast this morning, we will embark on a tour of this French-infused city that is brimming with culture. We’ll see some of the city’s most famous landmarks and admire the mix of old and new architectural styles before traveling to Quebec City to board the Norwegian Pearl for our 10-night cruise through Canada and New England. DAY 3 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 1 SAGUENAY (LA BAIE), QUEBEC (BLD) The city of Saguenay, formed in 2002, is comprised of three boroughs: La Baie, Chicoutimi, and Jonquiere. Chicoutimi and Jonquiere are situated on the shores of the Saguenay River and La Baie is found on the whimsically named, the Baie des Ha Ha! This French-speaking region is north of Quebec City and is considered a small oasis in the midst of the nearly uninhabited Canadian wilderness. -

Lettre Concierge

SOFITEL NEW YORK 45 WEST 44TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10036 Telephone: 212-354-8844 Concierge: 212-782-4051 HOTEL: WWW.SOFITEL-NEW-YORK.COM RESTAURANT: WWW.GABYNYRESTAURANT.COM FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK.COM/SOFITELNEWYORKCITY MONTHLY NEWSLETTER, JANUARY 2015 INSTAGRAM: SOFITELNYC SOFITELNORTHAMERICA SOFITEL NEW YORK TWITTER: @SOFITELNYC GABY EVENT HOTEL EVENT: STAY LONGER AND SAVE NATIONAL CHEESE LOVER’S DAY Tuesday January 20th 5PM – 9PM We invite you to join us for a cheese and wine tasting in cele- bration of national cheese lover’s This January, take a break and indulge in one of our unique Sofitel hotels in North America and Save! day. Please ask our restaurant for more details. Enjoy the magnificent views from the Sofitel Los Angeles at Beverly Hills, experience the energizing atmos- phere of Manhattan while staying at the Sofitel New York, soak in the warm sun by the pool of the Sofitel Miami and much more… Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington DC, San Francisco, Montreal, New York, Los Angeles and Miami. Discover all our Magnifique addresses. Book your reservation by Saturday, February 28th, 2015 and save up to 20% on your stay in all the Sofitel hotels in the US and Canada. With Sofitel Luxury Hotels, the longer you stay, the more you save. CITY EVENT BROADWAY A SLICE OF BROOKLYN MUSICAL THEATER SHOWS BUS TOURS “Hamilton” “Honeymoon in Vegas” Opens January 20th, 2015 Opens in January 15th The brilliant Lin’ Manuel’ Miranda opens his latest show, In previews now, a new musical comedy starring Tony Danza, “Hamilton,” a rap musical about the life of American Founding famous for the TV show “Who’s the Boss,” based on the 1992 Father Alexander Hamilton. -

Caractérisation Des Bandes Riveraines De La Rivière À Mars | 2013

2013 2013 Caractérisation des bandes riveraines de la rivière à Mars Ville de Saguenay Rapport technique Préparé pour la Ville de Saguenay i SIGNATURES Rapport préparé par : Le 27 août 2013 Alexandre Potvin Professionnel de l’environnement Chargé de bassin COBRAM Rapport vérifié par : Le 27 août 2013 Geneviève Brouillet-Gauthier, Biologiste Chargée de projet OBVS Caractérisation des bandes riveraines de la rivière à Mars ii ÉQUIPE DE RÉALISATION Organisme de bassin versant du Saguenay Coordination, planification et révision Marco Bondu, Directeur général OBVS Geneviève Brouillet-Gauthier, Chargée de projet OBVS Récolte ou traitement de données, rédaction Alexandre Potvin, Chargé de bassin COBRAM Geneviève Brouillet-Gauthier, Chargée de projet OBVS Stéphanie Lord, Chargée de projet OBVS Pablo Vilella, Stagiaire OBVS Caroline Caron, Bénévole OBVS Correctrice Maude Lemieux-Lambert, Secrétaire de direction OBVS Partenaires financiers et techniques Conseil d’arrondissement de La Baie, Ville de Saguenay Service Canada Regroupement des organismes de bassins versants du Québec REMERCIEMENTS Le Comité de bassin de la rivière à Mars (COBRAM) et l’Organisme de bassin versant du Saguenay (OBVS) tiennent à remercier les personnes et les organisations suivantes pour leur précieuse collaboration au projet : Service de l’aménagement du territoire et de l’urbanisme de la Ville de Saguenay; Service de géomatique de la Ville de Saguenay; Service des immeubles et de l’équipement de la Ville de Saguenay; Comité de soutien aux événements de la Ville de Saguenay; M. Gaétan Bergeron, Directeur général de l’arrondissement de La Baie. RÉFÉRENCE À CITER ORGANISME DE BASSIN VERSANT DU SAGUENAY. 2013. Caractérisation des bandes riveraines de la rivière à Mars, Rapport technique préparé pour Ville de Saguenay, Saguenay, 46 pages et 1 annexe. -

1 Atlantic Immigration Pilot Designated Employer List: The

Atlantic Immigration Pilot Designated Employer List: The following is a list of employers designated in New Brunswick through the Atlantic Immigration Pilot. This list does not indicate that these employers are hiring. To find current job vacancies got to www.nbjobs.ca. Liste des employeurs désignés Voici la liste des employeurs désignés sous le Projet pilote en matière d’immigration au Canada atlantique. Cette liste ne signifie pas que ces employeurs recrutent présentement.ss Pour les offres d’emploi, visitez le www.emploisnb.ca. Employer Name 3D Property Management 670807 NB Inc (Dépaneur Needs Caraquet & Shippagan) 693666 NB Inc. A & J Hanna Construction Ltd (Fredericton) A&W Miramichi (630883 NB Inc) A.C. Sharkey's Pub & Grill (Florenceville-Bristol) A.N.D. Communications A.R.Rietzel Landscaping Ltd Acadia Pizza Donair / Korean Restaurant (Dieppe) Acadia Veterinary Hospital Accor Hotels Global Reservation Centre Acorn Restaurant / Mads Truckstop (Lake George) Admiral's Quay B&B (Yang Developments Ltd.) Adorable Chocolat Inc Adrice Cormier Ltd Agence Résidentielle Restigouche Airport General Store (649459 NB Ltd) Airport Inn AirVM Albert's Draperies Alexandru & Camelia Trucking All Needs Special Care Inc. Allen, Paquet & Arseneau Allen's Petro Canada & Grocery (Allen's Enterprise Inc.) AL-Pack Amsterdam Inn & Suites Sussex (deWinter Brothers Ltd.) Andrei Chartovich 1 Employer Name Andrei Master Tailors Ltd Apex Industries Inc Appcast Armour Transport Inc Arom Chinese Cuisine Fredericton (655749 N.B. Ltd.) Asian Garden Indian Restaurant Moncton (Bhatia Brothers Ltd) Aspen University Association Multiculturelle du Restigouche Assurion Canada Inc Asurion Atelier Gérard Beaulieu Atlantic Ballet of Canada Atlantic Controls (Division of Laurentide Controls) Atlantic Home Improvement (656637 NB Inc) Atlantic Lottery Corporation Atlantic Pacific Transport Ltd. -

The Earlv Hudson's Bay ~Om~An;Account ~Ooksas SOU~~~Sfor Historical Research: an Analysis and Assessment

The Earlv Hudson's Bay ~om~an;Account ~ooksas SOU~~~Sfor Historical Research: An Analysis and Assessment "Truth isn't in accounts but in account books . 'The real history is written in forms not meant as hist~ry."~ The potential value of the business records of the fur-trading companies as sources for economic and ethnohistorical research has long been recog- ni~ed.~Indeed, some of the fur traders were aware of the historical value of the accounting records that they were keeping. Issac Cowie, for instance, served the Hudson's Bay Company in the Saskatchewan area in the 1860's and 1870's and subsequently wrote about his experiences. In his memoirs he included a section which dealt with the kinds of information that historians could find in the post business accounts. Also, he stressed that these records should be pre~erved.~Fortunately, most of the 18th-century business documents of the Hudson's Bay Company have survived, and in fact, the accounting records of the posts are frequently more complete than other lines of evidence such as correspondence files or daily journals of events. Yet, although scholars have been mindful of. the possible utility of business accounts for historical research, relatively little use has been made I The author would like to express his appreciation to the Hudson's Bay Company for granting him permission to consult and quote from the company's microfilm collection on deposit in the Public Archives of Canada. The reproductions of account book pages which were provided were also greatly appreciated. Also, I would like to thank the staff of the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa, particularly Peter Bower and Gary Maunder, for their friendly help. -

The Conquest of the Great Northwest Piled Criss-Cross Below Higher Than

The Conquest of the Great Northwest festooned by a mist-like moss that hung from tree to tree in loops, with the windfall of untold centuries piled criss-cross below higher than a house. The men grumbled.They had not bargained on this kind of voyaging. Once down on the west side of the Great Divide, there were the Forks.MacKenzie's instincts told him the northbranch looked the better way, but the old guide had said only the south branch would lead to the Great River beyond the mountains, and they turned up Parsnip River through a marsh of beaver meadows, which MacKenzie noted for future trade. It was now the 3rd of June.MacKenzie ascended a. mountain to look along the forward path. When he came down with McKay and the Indian Cancre, no canoe was to be found.MacKenzie sent broken branches drifting down stream as a signal and fired gunshot after gunshot, but no answer!Had the men deserted with boat and provisions?Genuinely alarmed, MacKenzie ordered McKay and Cancre back down the Parsnip, while he went on up stream. Whichever found the canoe was to fire a gun.For a day without food and in drenching rains, the three tore through the underbrush shouting, seeking, despairing till strength vas ethausted and moccasins worn to tattersBarefoot and soaked, MacKenzie was just lying down for the night when a crashing 64 "The Coming of the Pedlars" echo told him McKay had found the deserters. They had waited till he had disappeared up the mountain, then headed the canoe north and drifted down stream. -

Notre Dame De La Baie Academy

NOTRE DAME DE LA BAIE ACADEMY GREEN BAY, WISCONSIN PRESIDENT START DATE: JULY 2020 WWW.NOTREDAMEACADEMY.COM Mission Notre Dame de la Baie Academy, as an educational ministry of the Roman Catholic Church, educates the whole person by developing each student’s Christian faith, commitment to service, and full academic potential within a caring Church community. Fast Facts • 25.8: NDA’s Class of 2019 ACT Composite Score • 100%: Class of 2019 graduation rate • 98%: Class of 2019 graduates attending post-secondary education • 35: State championships since 1990 • 24,406: Proud alumni • $13.4 million: Scholarships offered to the Class of 2019 OVERVIEW Established in 1990 with the consolidation of three Catholic high schools, two of whom were founded more than 120 years ago, Notre Dame de la Baie Academy enjoys strong enrollment, deep and extensive alumni ties in the Green Bay community, high academic standards, and a welcoming, faith- based program that fosters the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual growth of each child. Infused with the charisms of the Norbertines and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, the school instills values of faith, respect, responsibility, service, and trustworthiness. An independent Catholic institution, Notre Dame Academy (NDA) enjoys the support of the Diocese of Green Bay and a close relationship with St. Norbert College, including the presence of three Norbertines on campus as teachers and spiritual advisors. The school is proud of its increasing economic and ethnic diversity and is committed to the Norbertine charism of openness to all. The school operates in the President/Principal Model and seeks a dynamic and visionary new President to collaborate with the Board of Trustees and Principal Patrick Browne to ensure the continued strength and vitality of the school.