Where Does a Woman Fit in a Mad Man's World? a Textual Analysis of Feminist Motifs Determined by the Production Values in Mad Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game of Thrones

OF MONSTERS Best looks on the small screen By Joe Nazzaro hoto by Jordin Althaus/AMC AND MEN P elevision really has become the new frontier as far as high-quality drama is concerned. Not only have numerous filmmakers made the increasingly effortless jump from big to small screen, but with the growing influence of on-demand programming, Tpay (and basic) cable and new means of content delivery popping up all the time, the quality gap between film and television is virtually imperceptible. With that in mind, Make-Up Artist catches up with a handful of today’s top small-screen series, from a departing favorite to a surprise streaming sensation. GAME OF THRONES ith Season Five of the fantasy series airing on HBO, and Season Six headed into production, it’s a busy time for prosthetic supervisor WBarrie Gower, who won an Emmy for the fourth-season episode “The Children” with make-up department head Jane Walker. “Going into Season Five, we felt much more confident about whatever they could throw at us, but it was probably double the amount of work as Season Four,” Gower says. “Episode eight, which is called ‘Hardhome,’ was on the scale of a huge movie, so this season has been a massive undertaking. “Our main returning character this season was the king of the White Walkers, called the Night’s King, played by Richard Brake, as well as three new White Walkers, all played by stuntmen, each wearing bespoke silicone prosthetics and lace wigs. We also had a new giant this season called Wun Wun, played by Ian Whyte, a major character in episode eight. -

Biggest Moments in Mad Men We Learn That Don's Girlfriend Midge Is

Biggest Moments In Mad Men We learn that Don's girlfriend Midge is in fact his mistress and he is actually married. Betty shoots the pigeons. We learn about Don's true identity Peggy and Stan get naked in the hotel Joan's room mate makes a pass at her Betty sets up her friend with the guy from the stables Don's brother Adam kills himself. We learn that Peggy is pregnant. Joan's fiancé (Greg Harris) rapes her in Don's office Roger has his first of two heart attack! Roger proposes to Jane Siegel, a secretary, and ends his marriage with Mona. Sal turns down the opportunity to sleep with Elliot. Sal is fired from SC. An unhappily and pregnant Betty has anonymous sex in a bar with a complete stranger. Freddie Rumsen pissing himself in the middle of an alcoholinduced blackout and is later fired. Don gets Roger to throw up after getting revenge for him making a pass at Betty. PPL buys out SC leaving Duck out of the deal. Betty finally gets access to Don's office drawer and learns about his true identity. Lois Sadler runs over Guy MacKendrick's foot with John Deere lawnmower in “Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency” Betty makes the decision to file for divorced and leave Don for Henry. Bert, Roger and Don are fired by Lane and then turn around and start SCDP. Anna Draper dies of cancer. Joan becomes pregnant with Rogers child and tries to pass the child off as Gregs. Don proposes to Megan. -

Adam Stier, Ties That Bind.Pdf

Ties That Bind: American Fiction and the Origins of Social Network Analysis DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Adam Charles Stier, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. David Herman, Advisor Dr. Brian McHale Dr. James Phelan Copyright by Adam Charles Stier 2013 Abstract Under the auspices of the digital humanities, scholars have recently raised the question of how current research on social networks might inform the study of fictional texts, even using computational methods to “quantify” the relationships among characters in a given work. However, by focusing on only the most recent developments in social network research, such criticism has so far neglected to consider how the historical development of social network analysis—a methodology that attempts to identify the rule-bound processes and structures underlying interpersonal relationships—converges with literary history. Innovated by sociologists and social psychologists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including Georg Simmel (chapter 1), Charles Horton Cooley (chapter 2), Jacob Moreno (chapter 3), and theorists of the “small world” phenomenon (chapter 4), social network analysis emerged concurrently with the development of American literary modernism. Over the course of four chapters, Ties That Bind demonstrates that American modernist fiction coincided with a nascent “science” of social networks, such that we can discern striking parallels between emergent network-analytic procedures and the particular configurations by which American authors of this period structured (and more generally imagined) the social worlds of their stories. -

Behind Every Mad Man There Is a Mad Woman

Behind Every Mad Man There Is a Mad Woman On Male and Female Representations and Sexuality in AMC’s Mad Men Ana Serediuc Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the Prof. dr. Gert Buelens requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en letterkunde: Italiaans-Engels” 2016 – 2017 Serediuc 2 Acknowledgements When I first started watching Mad Men it had never occurred to me that one day, I would write my dissertation about the show in order to obtain my master’s degree at the University of Ghent – and yet here we are a few years later. This pop-cultural topic of my choice did not always facilitate my research nor my writing process, but it did to a large extent made me greatly enjoy this entire journey. After experiencing some difficulties in finding a suitable subject matter, it was my supervisor who pointed me in the right direction. Therefore, I would like to express my gratitude to prof. dr. Gert Buelens, who not only helped me define my subject, but who has also put a lot of work in giving me thorough and supportive feedback. Furthermore, I would like to thank my friends and family for their amazing support not only during the realization of this master thesis, but throughout the entire duration of my academic studies. A special thanks to Kessy Cottegnie and Marjolein Schollaert for being such dedicated proof-readers and supporters. Serediuc 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………….. 2 Table of Contents …………………………………………………..…………………….. 3 List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………….… 4 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………... 5 I - Male and Female Roles………………………………………………………………. 10 Chapter 1 • Traditional and Modern Women ……………………………………...... -

Phd Manuscript 190429 Plain Text

The Presence of Performance and the Stakes of Serial Drama: Accrual, Transience, Companionship Elliott Logan MPhil (University of Queensland, 2013) BA, Hons (University of Queensland, 2009) BA (University of Queensland, 2007) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Communication and Arts Abstract This thesis shows how performance is a critically neglected but crucial aspect of serial television drama as an art form. One of serial drama’s obvious storytelling attractions is its ability to involve viewers in relationships between characters over long periods of time. Such involvement takes place through a recurring structure of episodes and seasons, whose unfolding reflects the extensive, ongoing history through which interpersonal bonds form and develop, deepen and decay. The characters we watch onscreen are embodied and performed by actors. Television studies, however, has persistently overlooked screen performance, hampering appreciation of serial drama’s affinity with long-term relationships as a resource for aesthetic significance. Redressing such neglect, this thesis directs new critical attention to expressive stylistic relationships between serial form, screen performance, and the subject of companionship in some recent US serial dramas. The focus of that attention is a particular aesthetic quality: the provisional, which emerges through serial drama’s distinctive tension between permanence and transience. In the first chapter, I argue that the provisional is central to an affinity between screen performance, seriality in television drama, and companionship as an aspect of human life. Chapters Two and Three then show how the art of the provisional in particular series has been underappreciated due to television studies’ neglect of performance and expressiveness as dimensions of serial form in television fiction. -

Women and Work in Mad Men Maria Korhon

“You can’t be a man. Be a woman, it’s a powerful business when done correctly:” Women and Work in Mad Men Maria Korhonen Master’s Thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Spring 2016 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. History of Working Women .................................................................................................................... 5 2. Appearance .................................................................................................................................................. 10 2.1. Appearance bias ................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1.1 Weight ................................................................................................................................................ 12 2.1.2. Beauty ideals ..................................................................................................................................... 15 2.1.3. 1960s Work Attire ............................................................................................................................. 18 2.1.4. Clothing and external image in the workplace .................................................................................. 20 2.1.5. Gender and clothing ......................................................................................................................... -

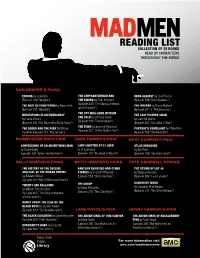

Reading List Collection of 25 Books Read by Characters Throughout the Series

READING LIST COLLECTION OF 25 BOOKS READ BY CHARACTERS THROUGHOUT THE SERIES DON DRAPER’S PICKS EXODUS by Leon Uris THE CHRYSANTHEMUM AND ODDS AGAINST by Dick Francis (Episode 106 “Babylon”) THE SWORD by Ruth Benedict (Episode 509 “Dark Shadows”) (Episode 405 “The Chrysanthemum THE BEST OF EVERYTHING by Rona Jaffe THE INFERNO by Dante Alighieri and the Sword”) (Episode 106 “Babylon”) (Episode 601-2 “The Doorway”) THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM MEDITATIONS IN AN EMERGENCY THE LAST PICTURE SHOW by John Le Carre by Frank O’Hara THE COLD by Larry McMurtry (Episode 413 “Tomorrowland”) (Episode 201 “For Those Who Think Young”) (Episode 607 “Man With a Plan”) THE FIXER by Bernard Malamud THE SOUND AND THE FURY by William PORTNOY’S COMPLAINT by Philip Roth (Episode 507 “At the Codfish Ball”) Faulkner (Episode 211 “The Jet Set”) (Episode 704 “The Monolith”) ROGER STERLING’S PICK JOAN HARRIS’S PICK BERT COOPER’S PICK CONFESSIONS OF AN ADVERTISING MAN LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER ATLAS SHRUGGED by David Ogilvy D. H. Lawrence by Ayn Rand (Episode 307 “Seven Twenty Three”) (Episode 103 "Marriage of Figaro") (Episode 108 “The Hobo Code”) SALLY DRAPER’S PICKS BETTY DRAPER’S PICKS PETE CAMPBELL’S PICKS THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE BABYLON REVISITED AND OTHER THE CRYING OF LOT 49 AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE STORIES by F. Scott Fitzgerald by Thomas Pynchon by Edward Gibbon (Episode 204 “Three Sundays”) (Episode 508 “Lady Lazarus”) (Episode 303 “My Old Kentucky Home”) GOODNIGHT MOON TWENTY ONE BALLOONS THE GROUP by Mary McCarthy by Margaret Wise Brown by William Pene -

Frontlist & Backlist Fall/Winter 2016

Fall/Winter 2016 TRADE Frontlist & Backlist 001-126_TC 2016-2_TAM.indb 1 30.05.16 11:04 001-126_TC 2016-2_TAM.indb 2 30.05.16 11:04 001-126_TC 2016-2_TAM.indb 1 30.05.16 11:04 001-126_TC 2016-2_TAM.indb 2 30.05.16 11:04 001-126_TC 2016-2_TAM.indb 1 30.05.16 11:04 Helmut Newton. NEw EDitiON New Deal Photography. JUNE The Eiffel Tower REvisED EDitiON Keiichi Tahara. AUgUst Work MAY USA 1935–1943 jUlY Architecture Fin-de-Siècle XL XL NEw TITLES Sc., 8.3 x 10.7 in., 280 pp. Hc., 5.5 x 7.7 in., 608 pp. Sc., 10.6 x 15 in., 176 pp. 978-3-8365-2688-3 $ 29.99 978-3-8365-3711-7 $ 19.99 978-3-8365-2703-3 $ 19.99 Alice Springs. JUNE Art for All. JUlY Christo and Jeanne-Claude. JUlY Urban Rooftops. AUgUst The Paris MEP Show The Color Woodcut in Vienna around 1900 The Floating Piers Islands in the Sky XL Hc., 8.3 x 10.8 in., 112 pp. Hc., 9.7 x 14.6 in., 416 pp. Sc. with flaps, 9.3 x 11.4 in., 128 pp. Hc., 9.5 x 12.5 in., 464 pp. Hc., 3 vols. in slipcase, 10.6 x 14.5 in., 1,016 pp. 978-3-8365-3973-9 $ 49.99 978-3-8365-3921-0 $ 69.99 978-3-8365-4783-3 $ 29.99 978-3-8365-6375-8 $ 69.99 978-3-8365-3057-6 $ 300 William Claxton. -

Sally, Part 33 a Waldorf-Astoria Wedding—1965

© 2010 Angela Bauer Sally, Part 33 A Waldorf-Astoria Wedding—1965 Fiction by Angela Bauer Nothing could have filled me with such joy as Gene running to greet Bobby and me when we returned to our house in Rye on Sunday, November 21, from a weekend in Manhattan with Daddy and his fiancée Megan Lachaille Calvert. Nanny Walsh told us that during the day Gene had pulled down his own trainers to use the toilet. She was sure Gene would soon be out of diapers at night. Bobby and I exchanged a look. Gene was only twenty-nine months old and soon would be sleeping without a diaper. Bobby was seven and I was eleven, yet we both still needed diapers and plastic panties in bed. Was Nanny Walsh deliberately being spiteful about us? Frankly, with everything else going on, especially Megan asking me to be a bridesmaid, I could care less about disapproval from Nanny Walsh. She knew when she took the job that Gene, Bobby and me needed diapers. By then Bobby was in trainers weekend days and wore regulation cotton underpants to school. So Nanny Walsh only needed to change Bobby once or twice a day. I had been washing nearly all the trainers and sheets since I was nine, until we moved to Rye and Mommy hired so many servants. Mommy had used the DyDee diaper service for years. Nanny Walsh had only pinned me into a diaper once, because Mommy told her to do that after spanking me. Since she had never needed to deal with my wet diapers, I could not see why she was complaining. -

The Relationship Between Children and the Elderly in Mad Men

Sustaining and transgressing borders. The relationship between children and the elderly in Mad Men Cecilia Lindgren and Johanna Sjöberg Book Chapter Cite this chapter as: Lindgren, C., Sjöberg, J. Sustaining and transgressing borders: The relationship between children and the elderly in Mad Men, In Joosen, V. (ed), Connecting childhood and old age in popular media, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi; 2018, pp. 184-206. ISBN: 9781496815163 Copyright: University Press of Mississippi The self-archived postprint version of this journal article is available at Linköping University Institutional Repository (DiVA): http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-147540 Sustaining and Transgressing Borders The Relationship Between Children and the Elderly in Mad Men Cecilia Lindgren and Johanna Sjöberg Children and the elderly are, in various contexts, portrayed as ideal companions, and positioned as “others” in relation to the more powerful generation in between (Joosen 128, 136-138; Hockey and James 2-5). In children’s literature, for example, the relationship between the two age groups tends to be romanticized, featuring their mutual interests in nature, animals, fantasy and storytelling. In this chapter, we explore how the two categories meet in the award-winning drama TV series Mad Men. The aim is to scrutinize the link between childhood and old age, by analyzing how the relationships between a young girl, Sally Draper, and her elderly relatives are played out. Exploring key scenes, we show how the companionship between children and the elderly is constructed as rewarding for both parties, yet as provocative and challenging rather than romantic and harmless. -

HOW to WATCH TELEVISION This Page Intentionally Left Blank HOW to WATCH TELEVISION

HOW TO WATCH TELEVISION This page intentionally left blank HOW TO WATCH TELEVISION EDITED BY ETHAN THOMPSON AND JASON MITTELL a New York University Press New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2013 by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell All rights reserved References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data How to watch television / edited by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8147-4531-1 (cl : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8147-6398-8 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Television programs—United States. 2. Television programs—Social aspects—United States. 3. Television programs—Political aspects—United States. I. Thompson, Ethan, editor of compilation. II. Mittell, Jason, editor of compilation. PN1992.3.U5H79 2013 791.45'70973—dc23 2013010676 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books. Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: An Owner’s Manual for Television 1 Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell I. TV Form: Aesthetics and Style 1 Homicide: Realism 13 Bambi L. Haggins 2 House: Narrative Complexity 22 Amanda D. -

THE CIRCUITRY of MEMORY: TIME and SPACE in MAD MEN by Molly Elizabeth Lewis B.A., Honours, the University of British Columbia, 2

THE CIRCUITRY OF MEMORY: TIME AND SPACE IN MAD MEN by Molly Elizabeth Lewis B.A., Honours, The University of British Columbia, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 © Molly Elizabeth Lewis, 2015 Abstract Memory is central to Mad Men (Matthew Weiner 2007-15) as a period piece set in the 1960s that activates the memories of its viewers while also depicting the subjective memory processes of its protagonist Donald Draper (Jon Hamm). Narratively, as much as Don may try to move forward and forget his past, he ultimately cannot because the memories will always remain. Utilizing the philosophy of Henri Bergson, I reveal that the series effectively renders Bergson’s notion of the coexistence of past and present in sequences that journey into the past without ever leaving the present. Mad Men ushers in a new era of philosophical television that is not just perceived, but also remembered. As a long-form serial narrative that intricately layers past upon present, Mad Men is itself an evolving memory that can be revisited by the viewer who gains new insight upon each viewing. Mad Men is the ideal intersection of Bergson’s philosophy of the mind and memory and Gilles Deleuze’s cinematic philosophy of time. The first chapter simply titled “Time,” examines the series’ first flashback sequence from the episode “Babylon,” in it finding the Deleuzian time- image. The last chapter “Space,” seeks to identify the spatial structure of the series as a whole and how it relates to its slow-burning pace.