ABDICATION of RESPONSIBILITY the Commonwealth and Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unhcr Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Asylum-Seekers from Sri Lanka

UNHCR ELIGIBILITY GUIDELINES FOR ASSESSING THE INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION NEEDS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS FROM SRI LANKA United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 21 December 2012 HCR/EG/LKA/12/04 NOTE UNHCR Eligibility Guidelines are issued by the Office to assist decision-makers, including UNHCR staff, Governments and private practitioners, in assessing the international protection needs of asylum- seekers. They are legal interpretations of the refugee criteria in respect of specific profiles on the basis of assessed social, political, economic, security, human rights and humanitarian conditions in the country/territory of origin concerned. The pertinent international protection needs are analyzed in detail, and recommendations made as to how the applications in question relate to the relevant principles and criteria of international refugee law as per, notably, the UNHCR Statute, the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, and relevant regional instruments such as the Cartagena Declaration, the 1969 OAU Convention and the EU Qualification Directive. The recommendations may also touch upon, as relevant, complementary or subsidiary protection regimes. UNHCR issues Eligibility Guidelines to promote the accurate application of the above-mentioned refugee criteria in line with its supervisory responsibility, as contained in paragraph 8 of its Statute in conjunction with Article 35 of the 1951 Convention and Article II of the 1967 Protocol, and based on the expertise it has developed over the years in matters related to eligibility and refugee status determination. It is hoped that the guidance and information contained in the Guidelines will be considered carefully by the authorities and the judiciary in reaching decisions on asylum applications. -

Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment Act No: 22 of 1994

United Nations CAT/C/LKA/3-4 Convention against Torture Distr.: General 23 September 2010 and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment Original: English or Punishment Committee against Torture Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 19 of the Convention Combined third and fourth periodic reports of States parties due in 2007 Sri Lanka*, **, *** [17 August 2009] * The second periodic report submitted by the Government of Sri Lanka is contained in document CAT/C/48/Add.2; it was considered by the Committee at its 671st and 674th meetings, held on 10 and 11 November 2005 (CAT/C/SR/671 and 674). For its consideration, see CAT/C/LKA/CO/2. ** In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. *** Appendices to the present document are available for consultation with the secretariat of the Committee. GE.10-46079 (E) 081110 CAT/C/LKA/3-4 Contents Paragraphs Page Abbreviations................................................................................................................................ 3 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 3 II. Positive aspects contained in the report of the Committee against Torture............. 6 5 III. Factors and difficulties impeding the implementation of the Convention set out in the report of the Committee against Torture ...................................................... -

SRI LANKA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

SRI LANKA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 4 July 2011 SRI LANKA 4 JULY 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA FROM 2 TO 27 JUNE 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 2 TO 27 JUNE 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ..................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Key political events (1948 to December 2010) ............................................... 3.01 The internal conflict (1984 to May 2009) ......................................................... 3.15 Government treatment of (suspected) members of the LTTE ........................ 3.28 The conflict's impact: casualties and displaced persons ................................ 3.43 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Key recent developments (January – May 2011) ........................................... 4.01 Situation -

The State of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Sri Lanka: a Joint

The State of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Sri Lanka: A Joint Civil Society Shadow Report to the United Nations Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights April 2017 1 Acknowledgement The preparation of this collective civil society shadow report has been coordinated by the Law & Society Trust. A number of organisations and individuals made particularly important contributions to this report in different ways. They include EQUAL GROUND, Janawabodaya Kendraya, Mannar Women’s Development Federation, National Fisheries Solidarity Movement, Suriya Women’s Development Centre, Women’s Resource Centre, Movement for Land and Agriculture Reforms, Movement for the Defense of Democratic Rights, Women’s Action Network, Women and Media Collective, Refugee Advocates, People’s Health Movement as well as Binendri Perera, Azra Jiffry, Rashmini de Silva, Anushka Kahandagama, Nilshan Fonseka, Iromi Perera, Aftab Lall, Nadya Perera, Vagisha Gunasekara, Muthulingam, Anushaya Collure, Vasuki Jeyasankar, Harini Amarasuriya, S. Elankovan, Sumika Perera, Dinushika Dissanayake. The final report has been compiled and prepared by Prashanthi Jayasekara with support from Sandun Thudugala, Vijay Nagaraj and Nigel Nugawela. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support by Democratic Reporting Initiative and technical support received from the Programme on Women’s Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ([email protected]) and its Executive Director, Ms Priti Darooka. 2 Introduction Context 01. Coming two years after a political transition from post-war authoritarianism, this Shadow Report to the United Nations Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights is framed in the backdrop of two concurrent processes of ‘transformation’ currently underway in Sri Lanka. The first is the process of constitutional reform initiated by the Government that was elected on the platform of restoring democratic, inclusive and accountable governance. -

Declaration of Joseph Asoka Nihal De Silva in Support of Defendant's Motion to Dismiss

Case 2:19-cv-02577-R-RAO Document 22-1 Filed 06/27/19 Page 1 of 55 Page ID #:125 1 JOHN C. ULIN (State Bar No. 165524) 2 [email protected] ARNOLD & PORTER KAYE SCHOLER LLP 3 777 South Figueroa Street, 44th Floor 4 Los Angeles, California 90017-5844 Telephone: (213) 243-4000 5 Facsimile: (213) 243-4199 6 Attorney for Defendant 7 Nandasena Gotabaya Rajapaksa 8 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA WESTERN DIVISION 11 12 AHIMSA WICKREMATUNGE, in her individual Case No. 2:19-cv-02577-R-RAO 13 capacity and in her capacity as the legal representative of the ESTATE OF LASANTHA Honorable Judge Manuel L. Real 14 WICKREMATUNGE, 15 DECLARATION OF JOSEPH Plaintiff, ASOKA NIHAL DE SILVA IN 16 SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT’S v. 17 MOTION TO DISMISS NANDASENA GOTABAYA RAJAPAKSA, 18 19 Defendant. 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 DECLARATION OF JOSEPH ASOKA NIHAL DE SILVA IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS Case 2:19-cv-02577-R-RAO Document 22-1 Filed 06/27/19 Page 2 of 55 Page ID #:126 1 I, Joseph Asoka Nihal de Silva, hereby declare as follows: 2 I. Introduction 3 1.1 I received my Bachelor of Laws Degree from the Law Faculty of the 4 University of Sri Lanka in 1971, was admitted to the bar by the Supreme Court of Sri 5 Lanka in 1972, and practiced law as an attorney-at-law of the Supreme Court. 6 1.2 I joined the Department of the Attorney-General on February 4, 1974, as a 7 State Counsel, which required that I appear as counsel for the State in civil and 8 criminal matters in both the original and appellate courts in Sri Lanka. -

An X-Ray of the Sri Lankan Policing System & Torture of the Poor

An X-ray of the Sri Lankan policing system & torture of the poor Editors Basil Fernando Shyamali Puvimanasinghe Asian Human Rights Commission Asian Human Rights Commission 2005 ISBN 962-8314-25-4 Published by Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) 19th Floor, Go-Up Commercial Building 998 Canton Road, Mongkok, Kowloon Hong Kong, China Telephone: +(852) 2698-6339 Fax: +(852) 2698-6367 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ahrchk.net September 2005 Printed by Clear-Cut Publishing and Printing Co. B1, 15/F, Fortune Factory Building 40, Lee Chung Street, Chai Wan, Hong Kong Table of Contents Preamble : Three Reports on Police Torture ................................................ 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 : Towards Eliminating Crime and Criminal links within the Policing System .................................................................... 19 Chapter 2 : Kadirgamar Killing Highlights Police Crisis ....................... 24 Chapter 3 : Women Speak Out: Interviews with Four Women ............ 28 Chapter 4: Equal access to Justice: Where Should it Begin to Ensure Human Rights? ............................................................ 52 Chapter 5 : Gerard Perera: One Man’s Courageous Fight for Justice .......................................................................................................... 60 Chapter 6 : Calling for an Inquiry to Probe into the Security Lapses that Resulted in the Assassination of Judge Ambepitiya -

Making Laws, Breaking Silence: Case Studies from the Field

Making Laws, Breaking Silence: Case Studies from the Field Making Laws, Breaking Silence: Case Studies from the Field grows out of a high level roundtable convened by Penn Law, UN Women, UNESCO, UN SDG Fund, and IDLO in March 2017. The convening brought together over 30 legislators, judges, and policy experts from more than 15 countries to examine new developments and challenges in gender equality lawmaking under Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals. The following case studies and essays expand on those deliberations and The Sustainable Development Goals seek interactions and highlight some tensions to change the history of the 21st century, in evolving law reform efforts around the addressing key challenges such as world. Closing the enforcement gap in poverty, inequality, and violence against gender equality laws is often called the st women and girls. The inalienable rights of “unfinished business of the 21 century.” gender equality and empowerment of These reflections offer fresh insights women and girls addressed in Goal 5 are and policy guidelines for UN agencies, a pre-condition for this. Despite decades multilaterals, government entities and of struggle by women’s movements and civil society organizations charged with reformist agendas, much still needs to gender-based law reform. be done to address de facto and de jure discrimination against women. At a time of enormous change for women, these essays from around the world are a critical analysis of the role of law in regulating and shaping women’s lives and calls for a reexamination of these laws in light of international women’s human rights guarantees. -

Revisiting Ten Emblematic Cases in Sri Lanka: Why Justice Remains

Revisiting Ten Emblematic Cases in Sri Lanka: Why Justice Remains Elusive Centre for Policy Alternatives January 2021 The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) is an independent, non-partisan organisation that focuses primarily on issues of governance and conflict resolution. Formed in 1996 in the firm belief that the vital contribution of civil society to the public policy debate is in need of strengthening, CPA is committed to programmes of research and advocacy through which public policy is critiqued, alternatives identified and disseminated. No. 6/5, Layards Road, Colombo 5, Sri Lanka Tel: +9411 2081384, +94112081385, +94112081386 Fax: +9411 2081388 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cpalanka.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: www.facebook.com/cpasl Twitter: @cpasl 1 Acknowledgments This report was researched and written by Bhavani Fonseka, Charya Samarakoon and Kushmila Ranasinghe. Comments on earlier drafts were provided by Dr Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu. The report was formatted by Ayudhya Gajanayake. CPA is grateful to all the individuals who supported the research by sharing information and insights. 2 Contents 1. Background 4 2. Brief Overview of Emblamatic Cases in Sri Lanka 8 3. Recommendations for Reform 12 Structural reform 11 Legislative reforms 18 4. Conclusion 24 Annexure I - Timeline and details of the ten emblematic cases 25 3 1. Background The cases discussed in this report are emblematic of the failings and inadequacies of the criminal justice system of Sri Lanka. They clearly demonstrate the multiple setbacks and barriers to justice and accountability. In the majority of these cases, victims and their families have been waiting for justice for over a decade, with slow progress at the investigative and prosecutorial stages. -

Contesting the Consent: an Analysis of the Law Relating to Marital Rape Exception in Sri Lanka

International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, Vol. 14, Issue 4 (December) ISSN 2289-1552 2017 CONTESTING THE CONSENT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE LAW RELATING TO MARITAL RAPE EXCEPTION IN SRI LANKA G.I.D. Isankhya Udani1 ABSTRACT In modern times, even though ‘marriage’ is regarded as a partnership of equals, the truth is the rights of married women are often restricted by social-cultural obstacles in the societies, where they live. Having emphasized the State Obligation under international treaty law, Article 16 (1) of the UDHR, Article 23 (4) of the ICCPR and Article 16 (1) (C) of the CEDAW declare that ‘men and women are entitled to equal rights as to marriage and during the marriage.’ However, criminalizing marital rape, in all circumstances remains controversial in many countries, despite their international obligations towards eliminating all forms of discrimination against women. In Sri Lanka, marital rape is not a criminal offence, unless the husband and wife are judicially separated. Therefore, this research argues that outlawing marital rape is a breach of international treaty obligations, as well as a violation of the Constitutional guarantee of equality before the law. On the other hand, the targets of the Goal 05 of the SDGs are to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Hence, legislative and social reluctance in abolishing ‘marital rape exception’ is a major obstruction to achieving the women’s empowerment and the practical realization of their fundamental rights. The main objective of this research is to make effective recommendations to protect women’s human rights during the marriage, by providing a strong safeguard against the marital rape. -

Religion, State, and a Conflict of Duties:A Constitutional Problem in Sri Lanka

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 8-2-2019 Religion, State, and a Conflict of Duties:A Constitutional Problem in Sri Lanka Sindhu De Livera University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation De Livera, Sindhu, "Religion, State, and a Conflict of Duties:A Constitutional Problem in Sri Lanka" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7781. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7781 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. Religion, State, and a Conflict of Duties: A Constitutional Problem in Sri Lanka By Sindhu De Livera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Faculty of Law in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Laws at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2019 © 2019 Sindhu De Livera Religion, State, and a Conflict of Duties: A Constitutional Problem in Sri Lanka By Sindhu De Livera APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ J. -

World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems

z6977# WORLD FACTBOOK OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS SRI LANKA N.H.A. Karunaratne University of Nevada, Las Vegas This country report is one of many prepared for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems under Bureau of Justice Statistics grant No. 90-BJ-CX-0002 to the State University of New York at Albany. The project director was Graeme R. Newman, but responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in each report is that of the individual author. The contents of these reports do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the U. S. Department of Justice. GENERAL OVERVIEW I. Political system. The national legislative body of Sri Lanka is the Parliament, which is a unicameral body, formerly called the National State Assembly or the House of Representatives. As of 1993, the parliament was composed of 225 members who are elected by the Sri Lankan citizens aged 18 years or older. The head of the Republic is the President, who is directly elected by the citizens aged 18 years or older. The term of the President is 6 years. The organization and financing of the justice system is the responsibility of the central government. The Provincial Councils may now maintain regional police departments. The executive branch of the government is composed of the President, the Prime Minister, and the cabinet. The Prime Minister is the head of government and the members of the cabinet are appointed by the President from among the Parliament members. The administrative structure consists of 8 provinces and 25 administrative districts. -

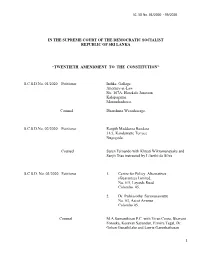

“Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution” Scsd

SC. SD No. 01/2020 - 39/2020 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA “TWENTIETH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION” S.C.S.D.No. 01/2020 Petitioner Indika Gallage Attorney-at-Law No. 167A, Horekele Junction Kalapugama Moronthuduwa. Counsel Dharshana Weraduwage. S.C.S.D.No. 02/2020 Petitioner Ranjith Madduma Bandara 31/3, Kandawatte Terrace Nugegoda. Counsel Suren Fernando with Khyati Wikramanayake and Sanjit Dias instructed by Lilanthi de Silva S.C S.D. No. 03/2020 Petitioner 1. Centre for Policy Alternatives (Guarantee) Limited, No. 6/5, Layards Road Colombo 05. 2. Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu No. 03, Ascot Avenue Colombo 05. Counsel M.A.Sumanthiran P.C. with Viran Corea, Bhavani Fonseka, Kesavan Sayandan, Ermiza Tegal, Dr. Gehan Gunathilake and Luwie Ganeshathasan 1 SC. SD No. 01/2020 - 39/2020 instructed by Sinnadurai Sundaralingam and Balendra. S.C.S.D. 04/2020 Petitioner Rajavarothium Sampanthan 176, Customs Road Trincomalee. Counsel Dr. K. Kanag-Isvaran P.C. with M.A.Sumanthiran P.C. Shivaan Kanag-Isvaran, Bhavani Fonseka and Aslesha Weerasekera instructed by Sinnadurai Sundaralingam and Balendra. S.C.S.D. 05/2020 Petitioner Hettithanthrige Anil Kariyawasam 56/1, St. Rita’s Road Mt. Lavinia. Counsel Chula Bandara with Anuradha Dias, Lakmini Edirisinghe Kanchana Madhushani Jayalath, Nadun M. Agampodi, Inesha Gunasena, Hasini P. de Silva and Kashyapa Divisekara instructed by K.J.K.Gayathri Kodagoda. S.C.S.D. 06/2020 Petitioner Nagananda Kodithuwakku General Secretary Vinivida Foundation Sri Lanka No. 99, Subadrarama Road Nugegoda Appeared in person. S.C.S.D. 07/2020 Petitioner S.C.C.