“Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution” Scsd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remarks by Hon. Rohitha Bogollagama Minister for Foreign Affairs “Financing Strategies for Healthcare”, 16Th March 2009

Welcome remarks by Hon. Rohitha Bogollagama Minister for Foreign Affairs “Financing Strategies for Healthcare”, 16th March 2009 Hon. Prime Minister, Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Healthcare and Nutrition, Distinguished Ministers, Representatives from UNDESA and WHO Excellencies, Representatives of UN Agencies, Distinguished Delegates, It is my great pleasure to welcome you to Colombo to the “Regional Ministerial Meeting on Financing Strategies for Healthcare”. I am particularly pleased to see participation from such a wide spectrum of stake-holders relevant to this meeting, including distinguished Ministers, Senior Officials, Representatives of UN Secretariat and agencies, Multilateral Organizations, NGOs and the Private Sector. This broad-based participation will enable us to address, from several perspectives, the challenges related to the subject of this Regional Meeting, the objective of which is to realize the health-related MDGS for the benefit of our people. I welcome in particular the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Myanmar, Minister of Health of Maldives, Minister of Finance of Bhutan and the Deputy Ministers of Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan and who have taken time off their busy schedules to gather here in Colombo. This meeting is organized under the framework of Annual Ministerial Review process of the Economic Social Council of the UN. The primary responsibility for overseeing progress in the achievement of the MDG’s by 1 the year 2015 devolves on the ECOSOC, and the Annual Ministerial Review process was established to monitor our progress in this regard. The theme for Review at Ministerial level at the ECOSOC in July this year is how we can work together to achieve the internationally agreed goals and commitments regarding global public health. -

Microsoft Word – MEDIAFREEDOMINSRILANKA

MEDIAFREEDOM IN SRILANKA Freedom of Expression news from Sri Lanka Monthly report No 04; period covered April 2009 List of Incidents 1. 01 st April 2009 - Editor assaulted 2. 09 th April 2009 - State media attacks news web site 3. 16 th April 2009 - Armed gang attacks Methodist church 4. 24 th April 2009 - State media levels charges against media groups 5. 26 th April 2009 - Journalist barred from visiting Sri Lanka 6. 26 th April - Sudar Oli editor released 7. 27 th April 2009 - TV regulations for new stations 8. 30 th April 2009 - No break through in investigations Other news: 1. April 2009 - Culture of silence takes over 2. 20 th April 2009 - Former editor recalled from Embassy posting 3. 24 th April 2009 - Media owners win election 4. 27 th April 2009 - foundation stone laid for SLWJA office building mediafreedom in srilanka Monthly report No 4, period covered April 2009 Page 1 of 4 Compiled by a group of journalists working voluntarily. In short: 01. 01 st April 2009 - Editor assaulted Editor M. I. Rahumathulla of the “Vaara Ureikal” weekly newspaper published in Kathakudi, Batticoloa was assaulted by an unidentified armed gang that broke into his house and had threatened him with death. Five masked men carrying clubs and swords broke into the house and the office of the journalist in Abranagar, Kathankudy around 10.45 pm, assaulted him several times on the head and slashed his hand causing serious wounds. The gang had smashed computers and other office ware before setting the place on fire and fleeing the scene. -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 70. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, May 18, 2016 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and the Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 70 Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Ports and Shipping Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis and Western Development Hon. Chandima Weerakkody, Minister of Petroleum Resources Development Hon. Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Hon. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

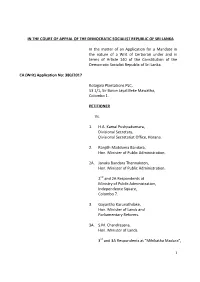

C.A WRIT 380/2017. Kotagala Plantations PLC Vs. H.A. Kamal

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an Application for a Mandate in the nature of a Writ of Certiorari under and in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. CA (Writ) Application No: 380/2017 Kotagala Plantations PLC, 53 1/1, Sir Baron Jayatilleke Mawatha, Colombo 1. PETITIONER Vs. 1. H.A. Kamal Pushpakumara, Divisional Secretary, Divisional Secretariat Office, Horana. 2. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Hon. Minister of Public Administration. 2A. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Hon. Minister of Public Administration. 2nd and 2A Respondents at Ministry of Public Administration, Independence Square, Colombo 7. 3. Gayantha Karunathilake, Hon. Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms. 3A. S.M. Chandrasena, Hon. Minister of Lands. 3rd and 3A Respondents at “Mihikatha Madura”, 1 No. 1200/6, Rajamalwatta Road, Sri Jayawardenepura, Kotte. 4. Sagala Rathnayake, Hon. Minister of Law and Order. 4A. Hon Maithripala Sirisena, Hon. Minister of Law and Order. 4B. Hon. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, Hon. Minister of Law and Order. 4th, 4A and 4B Respondents at 14th Floor, “Suhurupaya”, Subhuthipura Raod, Battaramulla. 5. Naveen Dissanayake, Hon. Minister of Plantation Industries, 13240, Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte. 5A. Hon. Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Industries and Export Agriculture, Sethsiripaya, 2nd Stage, Battaramulla. 6. Sri Lanka State Plantations Corporation, No. 11, Duke Street, Colombo 1. 7. Pujitha Jayasundera, Inspector General of Police (IGP), Police Headquarters, Colombo 1. 8. Hon. Attorney General, Attorney General’s Department. Colombo 12. RESPONDENTS 2 Before: Arjuna Obeyesekere, J / President of the Court of Appeal Counsel: Mahinda Nanayakkara with Nirosh Bandara and Wasantha Widanage for the Petitioner Ms. -

Minutes of Parliament for 11.09.2020

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 8.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Friday, September 11, 2020 at 10.30 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Douglas Devananda, Minister of Fisheries Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of Internal Security, Home Affairs and Disaster Management Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 8 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. -

Descendents All Mp3, Flac, Wma

Descendents All mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: All Country: US Released: 1987 Style: Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1791 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1728 mb WMA version RAR size: 1631 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 365 Other Formats: WMA MP3 ASF MMF DTS MIDI AHX Tracklist Hide Credits All 1 0:05 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson*, McCuistion* Coolidge 2 2:47 Lyrics By, Music By – Alvarez* No, All! 3 0:05 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson*, McCuistion* Van 4 3:01 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Alvarez*, Egerton* Cameage 5 3:05 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson* Impressions 6 3:08 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Egerton* Iceman 7 3:14 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Egerton* Jealous Of The World 8 4:04 Lyrics By, Music By – Aukerman* Clean Sheets 9 3:15 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson* Pep Talk 10 3:06 Lyrics By – Stevenson*, Aukerman*Music By – Aukerman* All-O-Gistics 11 3:04 Lyrics By – Stevenson*, McCuistion*Music By – Egerton* Schizophrenia 12 6:50 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Egerton* Uranus 13 2:15 Written-By – Descendents Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – SST Records Manufactured By – Laservideo Inc. – CI08141 Recorded At – Radio Tokyo Copyright (c) – Alltudemic Music Credits Bass, Artwork [Drawings] – Karl Alvarez Drums, Producer – Bill Stevenson Engineer – Richard Andrews Guitar – Stephen Egerton Management, Other [Booking] – Matt Rector Vocals – Milo Aukerman Vocals [Gator] – Dez* Notes Similar to Descendents - All except the disc is silver with blue lettering Recorded January 1987 at Radio Tokyo ℗ 1987 SST Records © 1987 Alltudemic Music (BMI) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 18861-0112-2 6 Matrix / Runout: MANUFACTURED IN U.S.A. -

New Faces in Parliament COLOMBO Sudarshani Fernandopulle Dr

8 THE SUNDAY TIMES ELECTIONS Sunday April 18, 2010 New faces in Parliament COLOMBO Sudarshani Fernandopulle Dr. Ramesh Pathirana UPFA Nimal Senarath UPFA Born in 1960 Born in 1969. S. Udayan (Silvestri Wijesinghe Doctor by profession. A medical doctor by profes- alantin alias Uthayan) Born in 1969. R. Duminda Silva Former DMO of the sion. Born in 1972. Educated at Kirindigalla MV Born 1974. Negombo Hospital. Son of former Education Studied at Delft Maha and Ibbagamuwa MV. Businessman. Served for more than 10 Minister Richard Pathirana. Vidyalaya. Profession – Businessman. Studied at St. Peter’s Col- years at the Children’s Health Studied at Richmond Col- Joined EPDP in 1992. UNP Organiser of Rambo- lege, Colombo. Care Bureau of the Health. lege, Galle. Former deputy Chairman of dagalla in 2006. Elected to the Western Pro- Chief Organiser of Akmeemana. the Karaveddy Pradeshiya Sabha. Elected to the North Western Provincial Coun- vincial Council in 2009 on the Executive Committee Member of the Cey-Nor cil in 2009. UPFA ticket and topped the preferential votes Fishing Net Factory. Father of two. list. Wasantha Senanayake SLFP Chief Organiser for Kolonnawa. Barister of Law. Studied at Sajin Vaas Gunawardene Awarded Deshabimana Deshashakthi Janaran- S. Thomas’ Prep. Graduated Born in 1973. WANNI PUTTALAM jana from the National Peace Association. Univ. Buckingham LLB. Prominent business Great grandson of Ceylon’s personality. UPFA UPFA first Prime Minister D. S. SLFP Galle District Senanayake and F.R. Organiser. Noor Mohommed Farook Victory Anthony Perera Thilanga Sumathipala Senanayake. President’s Coordinating Born in 1975. Native of Born in 1949. Born 1964 Secretary. -

SVAT RIS Details Report

SVAT RIS Details Report As at - 01/09/2021 TIN No Taxpayer Name SVAT No Project Name 104083846 02 DIC LANKA LTD SVAT000034 - 134009080 124 DESIGNS (PRIVATE) LIMITED 11289 - 114614238 20 CUBE LOGISTICS PVT LTD SVAT003133 - 114823554 247 TECHIES PVT LTD SVAT007440 - 102453379 3 D H BUILDING SOLUTIONS (PVT) LTD 11956 - 114676322 3 S FABRICATIONS PVT LTD SVAT001084 - 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD SVAT000182 - 114439568 3 S SECURITY SERVICE PVT LTD SVAT001351 - 114364045 3K HOLDINGS (PVT) LTD SVAT007345 - 114135216 3M LANKA PVT LTD SVAT002361 - 114234400 3RD WAVE CONSULTING (PRIVATE) LIMITED SVAT005184 - 114287717 4B INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD SVAT003345 - 114492256 505 SPECIAL WATCH PVT LTD SVAT004409 - 114828734 8 SIX GUARD SECURITY & INVESTIG.PVT LTD SVAT006452 - 103135532 98 HOLDINGS (PVT) LTD 11974 4 VILLA SMALL LUXURY HOTEL 134008520 99 X TECHNOLOGY LTD SVAT004975 - 114607649 A & A TRADING CO PVT LTD SVAT001090 - 174999546 A & R MANUFACTURING PVT LTD SVAT007399 A & R MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 174999546 A & R MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 10099 - 812141139 A A P T CHANDRADASA SVAT002880 - 114210730 A B C COMPUTERS (PRIVATE) LIMITED SVAT002230 - 114190497 A B C TRADE & INVESTMENTS PVT LTD SVAT004703 - 114197793 A B DEVELOPMENT PVT LTD SVAT001914 - 174959013 A B M BROTHERS PVT LTD SVAT007441 - 124006600 A B MAURI LANKA PVT LTD SVAT006403 - 114778710 A B S COURIER PVT LTD SVAT005369 - 114404543 A B SECURITAS PVT LTD SVAT002387 - 114474266 A B TRANSPORT PVT LTD SVAT005314 - 204008140 A BAUR & CO.PVT LTD SVAT002606 - 114263613 A C L KELANI MAGNET WIRE -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 134. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, December 06, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs and Minister of Lands Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare ( 2 ) M. No. 134 Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon.