Privateering in the Colonial Chesapeake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shipbuilding & Ocean Development Business Operation

Shipbuilding & Ocean Development Business Operation June 4, 2009 Shiro Iijima Director, Executive Vice President, General Manager, Shipbuilding & Ocean development Headquarters 1 Contents 1. FY2008 Overview -3 2. Shipbuilding & Ocean Development - 4 Business Environment 3. FY2009 Earnings Outlook -7 4. Outline of FY2009 Measures -8 5. Company-wide Special Measure -9 “Challenge 09” 6. Restructuring of Business Strategies -10 (Headquarters Business Plan) 2 1. FY2008 Overview Order Receipt Net sales Operating Profits • After Lehman shock, no ・Ship deliveries: 23 (+1 YoY) • Bottom line improved, new orders for Car carrier: 10 but profits were eroded commercial-use ships LNG carrier: 5 by provision for losses LPG carrier: 1 in ordered work arising • Public-sector orders held at normal level Container carrier: 2 from yen appreciation Patrol boat: 2 and higher prices for • Ships ordered: 18 (-14 YoY) Ferry: 1 steel, and other materials. 1H: 16 Others: 2 2H: 2 (public sector) ・Sales o par with previous 5-yr average Initial FY2008 target Previous 5-yr average: 320.4 JPY240.7 billion (JPY billion) (2003~2007) Decline in orders for (JPY billion) (JPY billion) commercial ships 353.6 271.3 283.9 240.1 4.0 1.6 2007 2008 2007 2008 2007 2008 3 2. Shipbuilding & Ocean Development Business Environment Lehman shock has caused major changes in marine transport and shipbuilding industries. 1) Marine transport industry <Seaborne cargo volume (actual and forecast)> 100億トン million ton <Before Lehman shock> 140 ・Increased seaborne cargoes ⇒ Tonnage shortages -

China's Merchant Marine

“China’s Merchant Marine” A paper for the China as “Maritime Power” Conference July 28-29, 2015 CNA Conference Facility Arlington, Virginia by Dennis J. Blasko1 Introductory Note: The Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook defines “merchant marine” as “all ships engaged in the carriage of goods; or all commercial vessels (as opposed to all nonmilitary ships), which excludes tugs, fishing vessels, offshore oil rigs, etc.”2 At the end of 2014, the world’s merchant ship fleet consisted of over 89,000 ships.3 According to the BBC: Under international law, every merchant ship must be registered with a country, known as its flag state. That country has jurisdiction over the vessel and is responsible for inspecting that it is safe to sail and to check on the crew’s working conditions. Open registries, sometimes referred to pejoratively as flags of convenience, have been contentious from the start.4 1 Dennis J. Blasko, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), a Senior Research Fellow with CNA’s China Studies division, is a former U.S. army attaché to Beijing and Hong Kong and author of The Chinese Army Today (Routledge, 2006).The author wishes to express his sincere thanks and appreciation to Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, U.S. Navy (Ret), for his guidance and patience in the preparation and presentation of this paper. 2 Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: Merchant Marine,” The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2108.html. According to the Factbook, “DWT or dead weight tonnage is the total weight of cargo, plus bunkers, stores, etc., that a ship can carry when immersed to the appropriate load line. -

Laws Adrift: Anchoring Choice of Law Provisions in Admiralty Torts

University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review Volume 17 Issue 1 Volume 17 Issue 1 (Fall 2009) Article 4 10-1-2009 Laws Adrift: Anchoring Choice Of Law Provisions In Admiralty Torts Marcus R. Bach-Armas Jordan A. Dresnick Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umiclr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Marcus R. Bach-Armas and Jordan A. Dresnick, Laws Adrift: Anchoring Choice Of Law Provisions In Admiralty Torts, 17 U. Miami Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 43 (2009) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umiclr/vol17/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAWS ADRIFT: ANCHORING CHOICE OF LAW PROVISIONS IN ADMIRALTY TORTS - Marcus R. Bach-Armas*& JordanA. Dresnick I. Introductory Remarks ........................ 44 II. The View from the Crow's Nest: Unwrapping Choice of Law Provisions ........................................... 46 III. The History of Maritime Tort Choice of Law Analysis .................................. 51 IV. Current Maritime Choice of Law Jurisprudence .................................... 55 V. Drafting for Naught: The (In)Significance of Choice of Law Clauses in Maritime Torts .................. 58 VI. The Role of Choice of Law Provisions in Maritime Torts Post-Bremen ............. 60 VII. Concluding Remarks .......................... 64 At the time of submission, Marcus R. -

Guide for Prospective Agricultural Cooperative Exporters Alan D

Abstract Guide for Prospective Agricultural Cooperative Exporters Alan D. Borst Agricultural Cooperative Service U.S. Department of Agriculture This report describes the different aspects of exporting that a U.S. agricul- tural cooperative must consider to develop a successful export program. t First, the steps involved in making the decision to export are covered. Then, information on various sources of assistance is given, along with , information on how to contact them. Next, features of export marketing strategy-the export plan, sales outlets, market research, product prepara- tion, promotion, and government export incentives-are discussed. Components of making the sale-the terms of sale, pricing, export finance, and regulatory concerns-are also included. Finally, postsale activities-documentation, packing, transportation, risk management, and buyer relations-are described. Keywords: cooperatives, agricultural exports. ACS Research Report 93 September 1990 Preface This report is solely a guide-not a complete manual or blueprint of oper- ations-for any individual cooperative wishing to export. Its objectives are to (1) help co-op management, personnel, and members with little or no experience in exporting to gain a better understanding of the export process, and (2) provide a basic reference tool for both experienced and novice exporters. As a guide, this report is not intended for use in resolving misunderstand- ings or disputes that might arise between parties involved in a particular export transaction. Nor does the mention of a private firm or product con- stitute endorsement by USDA. The author acknowledges the contribution of Donald E. Hirsch.’ ‘Donald E. Hirsch, Export Marketing Guide for Cooperatives, U.S. -

Legal and Economic Analysis of Tramp Maritime Services

EU Report COMP/2006/D2/002 LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF TRAMP MARITIME SERVICES Submitted to: European Commission Competition Directorate-General (DG COMP) 70, rue Joseph II B-1000 BRUSSELS Belgium For the Attention of Mrs Maria José Bicho Acting Head of Unit D.2 "Transport" Prepared by: Fearnley Consultants AS Fearnley Consultants AS Grev Wedels Plass 9 N-0107 OSLO, Norway Phone: +47 2293 6000 Fax: +47 2293 6110 www.fearnresearch.com In Association with: 22 February 2007 LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF TRAMP MARITIME SERVICES LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF TRAMP MARITIME SERVICES DISCLAIMER This report was produced by Fearnley Consultants AS, Global Insight and Holman Fenwick & Willan for the European Commission, Competition DG and represents its authors' views on the subject matter. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or DG Competition's views. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. © European Communities, 2007 LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF TRAMP MARITIME SERVICES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The consultants would like to thank all those involved in the compilation of this Report, including the various members of their staff (in particular Lars Erik Hansen of Fearnleys, Maria Bertram of Global Insight, Maria Hempel, Guy Main and Cécile Schlub of Holman Fenwick & Willan) who devoted considerable time and effort over and above the working day to the project, and all others who were consulted and whose knowledge and experience of the industry proved invaluable. -

Volume Contracts of Affreightment – Some Features and Principles

Volume Contracts of Affreightment – Some Features and Principles Lars Gorton 1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………….…. 62 1.1 General Background ……………………………………………………… 62 1.2 Some Contractual Points …………..……………………………………... 62 1.3 Frame Agreements ………………………………………………………... 64 1.4 Some General Points Related to Distributorship Agreements and Volume Contracts ………………………………………. 66 1.5 Some Further Overriding Points ……………………………………….…. 67 2 Contract Forms ………………………………………………………………… 68 3 Law, Contract and Terminology ……………………………………………… 69 4 The SMC Rules on Volume Contracts ……………………………………..…. 70 5 Characteristics of COA’s ……………………………………………………… 71 6 The Generic Nature of the COA ………………………………………………. 72 7 Some of the Parameters of the COA ………………………...……………….. 76 7.1 The Ships Involved Under the Volume Contract ………………………… 76 7.2 Time Elements in Connection with COA’s ………………………………. 76 7.3 Cargo and Cargo Quantity and Planning of Voyages ………………….… 77 8 Breach and Consequences of Breach …………………………………………. 78 8.1 Generally, Best Efforts and Cooperation …………………………………. 78 8.2 Consequences of the Owners’s Breach …………………………………... 78 8.3 Consequences of the Charterer’s Breach …………………………………. 78 9 Some Comparisons with Distributorship Agreements in English Law ….…. 78 10 Some COA Cases Involving “Evenly spread” ……………………………….. 82 10.1 “Evenly spread” …………………………………………………………... 82 10.2 Mitigation of Damages …………………………………………………… 85 11 Freight, Demurrage and Similar ……………………………………………… 88 11.1 General Points ………..…………………………………………………... 88 11.2 Freight Level …………………………………………………………….. -

Property, Soverignty, Commerce and War in Hugo Grotius De Lure Praedae - the Law of Prize and Booty, Or "On How to Distinguish Merchants from Pirates" Ileana M

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 31 | Issue 3 Article 5 2006 Constructing International Law in the East Indian Seas: Property, Soverignty, Commerce and War in Hugo Grotius De lure Praedae - The Law of Prize and Booty, or "On How to Distinguish Merchants from Pirates" Ileana M. Porras Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Ileana M. Porras, Constructing International Law in the East Indian Seas: Property, Soverignty, Commerce and War in Hugo Grotius De lure Praedae - The Law of Prize and Booty, or "On How to Distinguish Merchants from Pirates", 31 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol31/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. CONSTRUCTING INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE EAST INDIAN SEAS: PROPERTY, SOVEREIGNTY, COMMERCE AND WAR IN HUGO GROTIUS’ DE IURE PRAEDAE—THE LAW OF PRIZE AND BOOTY, OR “ON HOW TO DISTINGUISH MERCHANTS FROM PIRATES” Ileana M. Porras* I. INTRODUCTION hroughout history, and across the globe, peoples and nations have Tencountered and entered into relationship with one another. While keeping in mind the dangers of oversimplification, it could nevertheless be argued that despite their variety, international relations fall mostly into either of two familiar types: The first takes the form of war or con- quest, while the second pertains to commerce or international trade.1 It is evident that these two categories are not mutually exclusive; war and trade have often gone hand in hand. -

1Judge John Holland and the Vice- Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1797-1803: Some Introductory and Biographical Notes (Part 1)

1JUDGE JOHN HOLLAND AND THE VICE- ADMIRALTY COURT OF THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE, 1797-1803: SOME INTRODUCTORY AND BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES (PART 1) JP van Niekerk* ABSTRACT A British Vice-Admiralty Court operated at the Cape of Good Hope from 1797 until 1803. It determined both Prize causes and (a few) Instance causes. This Court, headed by a single judge, should be distinguished from the ad hoc Piracy Court, comprised of seven members of which the Admiralty judge was one, which sat twice during this period, and also from the occasional naval courts martial which were called at the Cape. The Vice-Admiralty Court’s judge, John Holland, and its main officials and practitioners were sent out from Britain. Key words: Vice-Admiralty Court; Cape of Good Hope; First British Occupation of the Cape; jurisdiction; Piracy Court; naval courts martial; Judge John Holland; other officials, practitioners and support staff of the Vice-Admiralty Court * Professor, Department of Mercantile Law, School of Law, University of South Africa. Fundamina DOI: 10.17159/2411-7870/2017/v23n2a8 Volume 23 | Number 2 | 2017 Print ISSN 1021-545X/ Online ISSN 2411-7870 pp 176-210 176 JUDGE JOHN HOLLAND AND THE VICE-ADMIRALTY COURT OF THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE 1 Introduction When the 988 ton, triple-decker HCS Belvedere, under the command of Captain Charles Christie,1 arrived at the Cape on Saturday 3 February 1798 on her fifth voyage to the East, she had on board a man whose arrival was eagerly anticipated locally in both naval and legal circles. He was the first British judicial appointment to the recently acquired settlement and was to serve as judge of the newly created Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope. -

Stevedoring Level 1

LEARNERS GUIDE Transport and Logistics - Stevedoring Level 1 Commonwealth of Learning (COL) Virtual University for Small States of the Commonwealth (VUSSC) Copyright The content contained in this course’s guide is available under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike License. You are free to: Share – copy, distribute and transmit the work Remix – adapt the work. Under the following conditions: Attribution – You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Share Alike – If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same, similar or a compatible license. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ Commonwealth of Learning (COL) December 2009 The Commonwealth of Learning 1055 West Hastings St., Suite 1200 Vancouver BC, V6E 2E9 Canada Fax: +1 604 775-8210 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www. www.col.org/vussc Acknowledgements The VUSSC Team wishes to thank those below for their contribution to this Transport and Logistics / Stevedoring - Level 1 learners’ guide. Alexandre Alix Bastienne Seychelles, Africa Fritz H. Pinnock Jamaica, Caribbean Mohamed Liraar Maldives, Asia Ibrahim Ajugunna Jamaica, Caribbean Maxime James Antigua and Barbuda, Caribbean Griffin Royston St Kitts and Nevis, Caribbean Vilimi Vakautapola Vi Tonga, Pacific Neville Asser Mbai Namibia, Africa Kennedy Glenn Lightbourne Bahamas, Caribbean Glenward A. -

Lusardi 1999- Blackbeard Shipwreck Project with a Note on Unloading A

The Blackbeard Shipwreck Project, 1999: With a Note on Unloading a Cannon By: Wayne R. Lusardi NC Underwater Archaeological Conservation Laboratory Institute of Marine Sciences 3431 Arendell Street Morehead City, North Carolina 28557 Lusardi ii Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 1999 Field Season.................................................................................................................................1 Figure 1: Two small cast-iron cannons during removal of concretion and associated ballast stones. ...................................................................................................................................1 The Artifacts .........................................................................................................................................2 Ship Parts and Equipment...................................................................................................................2 Arms...................................................................................................................................................2 Figure 2: Weight marks on breech of cannon C-21..............................................................3 Figure 3: Contents of cannon C-19 included three iron drift pins, a solid round shot and three wads of cordage.........................................................................................................3 -

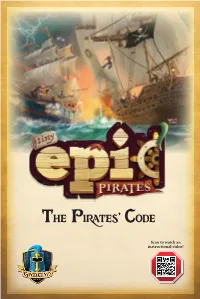

The Pirates' Code

The Pirates’ Code Scan to watch an instructional video! Components Legend Legend Legend Dread Legend Dread Dread Pirate Sure-fire Dread Pirate Sure-fire Pirate Sure-fire Pirate - Buccaneer Sure fire Buccaneer Buccaneer Buccaneer Swash 1 Market Mat Swash Buckler Swash Buckler Swash Buckler Buckler Corsair Corsair Corsair Corsair Pirate Pirate Pirate Pirate Sea Dog Sea Dog Sea Dog Repair Sea Dog Repair Repair Extort Repair Extort : Extort Cannons: Extort Cannons: Cannons: Rigging 1 Cannons Rigging 1 Rigging 1 1 Rigging 1 1 2 Port Tokens 1 1 4 Legend Mats 4 Helm Mats 16 Map Cards 8 8 6 6 6 4 4 4 2 2 2 1-4 1-4 1-3 1-3 1-3 1-2 1-2 1-2 . Cpt. Carmen RougeCpt Morgan Whitecloud FRONTS . Francisco de Guerra Cpt. Magnus BoltCpt BACKS 11 Merchant Cards 4 Double-Sided Captain Cards Alice O’Malice 1 Doc Blockley Lisa Legacy Sydney Sweetwater Buck Cannon Betty Blunderbuss Eliza Lucky Ursula Bane Willow Watch Taylor Truenorth Quartermaster Quigley Jolly Rodge Silent Seamus Lieutenant Flint Raina Rumor Black-Eyed Brutus Pale Pim 2 Salty Pete 2 Cutter Fang BACKS Sara Silver Jack “Fuse” Rogers Chopper Donovan Sally Suresight FRONTS Tina Trickshot 24 Crew Cards BACKS BACKS FRONTS 20 Search Tokens FRONTS 20 Order Tokens (5 in 4 colors) 2 4 Pirate Ships (in 4 colors) 2 Merchant Ships (in 2 colors) 1 Navy Ship 4 Captains (in 4 colors) 16 Deckhands 4 Legend Tokens 12 Treasures (4 in 4 colors) (in 4 colors) (3 in 4 colors) 1 Booty Bag 40 Booty Crates 4 Gold 3 Dice 12 Sure-fire Tokens (10 in 4 colors) Doubloons Prologue You helm a notorious pirate ship in the swashbuckling days of yore. -

The Latest Chapter of the American Law of Prize and Capture

THE LATEST CHAPTER OF THE AMERICAN LAW OF PRIZE AND CAPTURE. With the distribution of a small prize fund in the case of Charles H. Davis, Captain, U. S. N., et al. v. The Paz, Ventura and other vessels and properry, under a decree of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, entered April 24, 1905, the law of naval prize in the United States became a purely historical and academic subject. That decree was the last to be entered in regard to property captured by the American naval forces in the Spanish war, and Section 13 of the Act of March 3, 1899,' had repealed "all provisions of law authorizing the distribu- tion among captors of the whole or any portion of the pro- ceeds of vessels, or any property hereafter captured, con- demned as prize, or providing for the payment of bounty for the sinking or destruction of vessels of the enemy hereafter occurring in time of war." Hereafter, in what- ever wars the United States may be engaged, the property of the enemy's government and of its citizens may be subject to capture, but the captors will have no personal interest in such capture as long as the law remains as it is to-day. Theoretically speaking, of course, Congress may at any time restore the old prize system, but such action on its part is most improbable. With the advance of civilization, war has gradually been losing its predatory character, and the abolition of prize rights is but one of many steps in that advance.