Dilated Cardiomyopathies in Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dane Line Reimagined

Dane Line Reimagined Published by the Great Dane Club of New England January 2021 Be Sure to Join Us for Our Up-Coming Shows: Supported Entry at the Chickadee Classic, Maine June 26-27, 2021 2021 Fall Specialties Thanksgiving Classic Springfield November 27-28 The shows will fall on Thanksgiving weekend President—Sue Davis Shaw Vice President—Marcia Roddy Recording Secretary—Kim Thurler Corresponding Secretary—Tiffany Cross Treasurer—Sharon Boldeia Directors—Suzanne Kelley, Normand Vadenais & Dianne Powers President’s Letter January 2021 Happy New Year everyone! I know it will be a better one for all of us. Welcome to the first issue of our ‘bigger and better’ bulletin thanks to the talented Carol Urick. Carol was the editor of Daneline for many years and evolved it into the wonderful publication that it was. We only ended it due to lack of funds in the club and the increasing cost of publication. Since I’ve been doing Throwback Thursday, I’ve heard from several people across the country who told me that they looked forward to getting it each year at the National. I hope everyone will get on board with getting your brags and litters listed. We are planning an every other month publication so the next deadline should be March 1st. I would like to welcome our new Associate Members, Michelle Hojdysz from New Rochelle, NY and Anne Sanders from Gardiner, NY. We hope to actually meet you in person when dog shows open up again. January is the month when we hold our annual meeting and election of officers. -

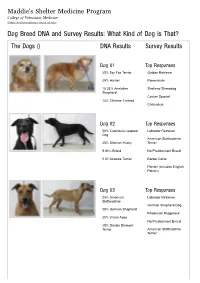

Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog Is That? the Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results

Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program College of Veterinary Medicine (https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu) Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog is That? The Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results Dog 01 Top Responses 25% Toy Fox Terrier Golden Retriever 25% Harrier Pomeranian 15.33% Anatolian Shetland Sheepdog Shepherd Cocker Spaniel 14% Chinese Crested Chihuahua Dog 02 Top Responses 50% Catahoula Leopard Labrador Retriever Dog American Staffordshire 25% Siberian Husky Terrier 9.94% Briard No Predominant Breed 5.07 Airedale Terrier Border Collie Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 03 Top Responses 25% American Labrador Retriever Staffordshire German Shepherd Dog 25% German Shepherd Rhodesian Ridgeback 25% Lhasa Apso No Predominant Breed 25% Dandie Dinmont Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Dog 04 Top Responses 25% Border Collie Wheaten Terrier, Soft Coated 25% Tibetan Spaniel Bearded Collie 12.02% Catahoula Leopard Dog Briard 9.28% Shiba Inu Cairn Terrier Tibetan Terrier Dog 05 Top Responses 25% Miniature Pinscher Australian Cattle Dog 25% Great Pyrenees German Shorthaired Pointer 10.79% Afghan Hound Pointer (includes English 10.09% Nova Scotia Duck Pointer) Tolling Retriever Border Collie No Predominant Breed Dog 06 Top Responses 50% American Foxhound Beagle 50% Beagle Foxhound (including American, English, Treeing Walker Coonhound) Harrier Black and Tan Coonhound Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 07 Top Responses 25% Irish Water Spaniel Labrador Retriever 25% Siberian Husky American Staffordshire Terrier 25% Boston -

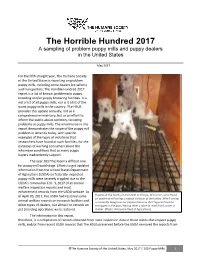

2017 Horrible Hundred Report

The Horrible Hundred 2017 A sampling of problem puppy mills and puppy dealers in the United States May 2017 For the fifth straight year, The Humane Society of the United States is reporting on problem puppy mills, including some dealers (re-sellers) and transporters. The Horrible Hundred 2017 report is a list of known, problematic puppy breeding and/or puppy brokering facilities. It is not a list of all puppy mills, nor is it a list of the worst puppy mills in the country. The HSUS provides this update annually, not as a comprehensive inventory, but as an effort to inform the public about common, recurring problems at puppy mills. The information in this report demonstrates the scope of the puppy mill problem in America today, with specific examples of the types of violations that researchers have found at such facilities, for the purposes of warning consumers about the inhumane conditions that so many puppy buyers inadvertently support. The year 2017 has been a difficult one for puppy mill watchdogs. Efforts to get updated information from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) on federally-inspected puppy mills were severely crippled due to the USDA’s removal on Feb. 3, 2017 of all animal welfare inspection reports and most enforcement records from the USDA website. As of April 20, 2017, the USDA had restored some Puppies at the facility of Alvin Nolt in Thorpe, Wisconsin, were found on unsafe wire flooring, a repeat violation at the facility. Wire flooring animal welfare records on research facilities and is especially dangerous for puppies because their legs can become other types of dealers, but almost no records on entrapped in the gaps, leaving them unable to reach food, water or pet breeding operations were restored. -

The Banter Bulldogge Was Created by Todd Tripp of Sout

properly socialized. They are well suited as a watchdog and will alert to danger or trespassers. They are ready and willing to protect if necessary. Disqualifications: viciousness or extreme shyness Size: Dogs excessively above or below the Banter Bulldogge Breed Standard standard weight/height should be seriously faulted. Recognized by the AMA in 2016 Male: An ideal male should be 21 to 24 Background: The Banter Bulldogge was inches tall at the withers and weigh 50- created by Todd Tripp of Southeast Ohio in the 85lbs. late 1990's. His vision was to re-create the now extinct Brabanter Bullenbeisser of the 1700's Female: An ideal female should be 20 from the Belgium province known as Brabant. to 23 inches tall at the withers and weigh There were two regional varieties, the Brabanter 50-75lbs. Bullenbeisser and the Danziger Bullenbeisser. The Brabanter Bullenbeisser was the smaller Head: The Banter Bulldogge head is square and more bully type dog that was well-known as a muscular. The head should have a pronounced hunting dog. Its task was to seize the prey and stop between skull and muzzle with the top of hold it until the hunters arrived. It is generally the skull mostly flat with strong muscular accepted that the Brabanter Bullenbeisser was a cheeks. direct ancestor of today's Boxer. The Banter Serious faults: narrow or long head Bulldogge’s foundation mainly consisted of Boxers but other Molosser breeds such as the Eyes: Rounded almond eyes that are wide set American Pitbull Terrier, American with a wrinkled brow for a look of heavy Staffordshire Terrier, and American Bulldog concentration. -

The Giant Hotline

A Quarterly Publication of the South Central Giant Schnauzer Club The Giant Hotline Volume XI, Issue 1 January 2014 SCGSC’s 11th Annual SPRING FLING 2014 FALL ROUND-UP SCGSC’s 2014 Spring Fling is con- firmed for Saturday, April 26, 2014 from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. at Bear The annual Fall Round-Up was held on October 19 at Creek Park, Pavilion #1. The park is South Fork Ranch in Parker, Texas. Giants and their located at 400 Bear Creek Parkway in owners started the day’s festivities with time to meet Keller, Texas. new friends and renew old friendships. Please bring your favorite “pot More than 60 people attended this year’s celebration. luck”dish, beverage, and a folding After enjoying the barbecue buffet, a short meeting was chair. SCGSC will provide a main held, followed by the club meeting, then on to the Cos- entrée, paper products and bottled tume Parade and Raffle. water. Need additional info? Contact Jane Special thanks to Jane Chism for coordinating the Chism. day’s events. Hope you can join us! Additional photos from the day are found elsewhere in this issue. In this Issue . President’s Column . 2 Barn Hunt . 3 Grooming Hints . 4 Problems Associated with Adopting Two Puppies At A Time. 5 Happy Endings . .. 10 Robyn’s Hints.—CPR for Dogs. 11 Beginner’s Guide to Dog Shows Pt.2 . .12 Senior Giants. 15 Southern Regional Specialty . 17 SCGSC Show Results . .20 Cooking for Giants . .21 Jack’s Corner. 22 Meet Madam Meg . 22 Memorials . -

Australian National Kennel Council Ltd the Boxer

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL LTD Extended Breed Standard of THE BOXER Produced by National Boxer Council (Australia) in conjunction with The Australian National Kennel Council Ltd Standard adopted by Kennel Club London pre 1987 Standard adopted by ANKC Ltd pre 1987 FCI Standard No: 144 Breed Standard Extension adopted by ANKC Ltd 2011 Copyright Australian National Kennel Council Ltd 2011 Country of Origin ~ Germany Extended Standards are compiled purely for the purpose of training Australian judges and students of the breed. In order to comply with copyright requirements of authors, artists and photographers of material used, the contents must not be copied for commercial use or any other purpose. Under no circumstances may the Standard or Extended Standard be placed on the Internet without written permission of the ANKC Ltd. THE BOXER Other breeds have pronounced specialised talents . hunting, herding, trailing, and so on . but for a combination of the outstanding virtues of many with the faults of a few, our Boxer is the most gifted of canines. For the man, woman or child who wants an all-round dog, he has no equal. No other dog is more individual in appearance, more keenly intelligent or sanely even-tempered. These virtues alone are priceless if the dog is to become part of his master’s family, which he should for the well being of all concerned. The Boxer has a faculty of worming his way into the good graces and the hearts of an entire household. He seems to offer something special to each person he meets. It’s astonishing, but true . -

Agtsec AKC Catalog

Waco Agility Group AKC Sanctioned Agility Trial Belton, TX Judge: Karen Wlodarski, Johns Island, NC CLASS SCHEDULE Friday, May 14, 2021 Ring 1: Combined FAST - 54 Entries Master/Excellent Standard - 93 Entries Premier Standard - 34 Entries Open Standard - 8 Entries Novice Standard - 9 Entries Ring 2: Premier JWW - 33 Entries Master/Excellent JWW - 95 Entries Open JWW - 9 Entries Novice JWW - 9 Entries Saturday, May 15, 2021 Ring 1: Combined FAST - 53 Entries Master/Excellent Standard - 97 Entries Premier Standard - 39 Entries Open Standard - 10 Entries Novice Standard - 6 Entries Ring 2: Premier JWW - 36 Entries Master/Excellent JWW - 98 Entries Open JWW - 10 Entries Novice JWW - 7 Entries Sunday, May 16, 2021 Ring 1: Combined FAST - 59 Entries Master/Excellent Standard - 94 Entries Open Standard - 12 Entries -1- CLASS SCHEDULE (cont.) Sunday, May 16, 2021 (cont). Ring 1 (cont.): Novice Standard - 10 Entries Ring 2: Master/Excellent JWW - 92 Entries Open JWW - 16 Entries Novice JWW - 11 Entries Time 2 Beat - 30 Entries PLEASE BE ATTENTIVE TO ANNOUNCEMENTS THROUGHOUT THE EVENT FOR LAST MINUTE CHANGES. There are 167 dogs entered in this event with 344 entries on Friday, 356 entries on Saturday, and 324 entries on Sunday for a total of 1024 entries. Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club for holding of this event under American Kennel Club rules and regulations. Gina Dinardo, Secretary. -2- Breed List Summary - Std/JWW Novice Open Master/Excellent Herding Group Australian Cattle Dog 0/0 0/0 4/4 Australian Shepherd 1/1 0/0 -

Common Breed-Associated Heart Diseases of Dogs and Cats

Animal Emergency & Referral Associates 1237 Bloomfield Ave., Fairfield, NJ 07004 973-226-3282 www.animalerc.com Gordon D. Peddle, VMD, DACVIM (Cardiology) Director of the Cardiology Section, AERA Internal Medicine Department Common Breed-associated Heart Diseases of Dogs and Cats DOGS CONGENITAL DISEASES Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) . Bichon Frise . Chihuahua . Cocker Spaniel . Collie . English Springer Spaniel . German Shepherd . Keeshond . Labrador Retriever . Maltese . Newfoundland . Poodle . Pomeranian . Shetland Sheepdog . Yorkshire Terrier Subaortic stenosis . Bouvier des Flanders . Boxer . English Bulldog . German Shepherd . German Shorthair Pointer . Golden Retriever . Great Dane . Newfoundland . Rottweiler . Samoyed Valvular aortic stenosis . Bull Terriers 1 Pulmonic stenosis . Airedale Terrier . Beagle . Boykin Spaniel . Boxer . Chihuahua . Cocker Spaniel . English Bulldog . Bull Mastiff . Samoyed . Schnauzer . West Highland White Terrier Tetralogy of Fallot . Keeshond . English Bulldog . Miniature Poodle . Wire-haired Fox Terrier Mitral valve dysplasia . Bull Terrier . German Shepherd . Great Dane Tricuspid valve dysplasia . Labrador Retriever . Old English Sheepdog Atrial septal defect . Standard Poodle ACQUIRED DISEASES Degenerative atrioventricular (AV) valve disease . Cavalier King Charles Spaniel . Chihuahua . Dachshund . Miniature Poodle . Pomeranian . Yorkshire Terrier . Small breed dogs, in general Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) . Doberman Pinscher . Great Dane . Irish Wolfhound . Scottish Deerhound . Boxer . Large -

FCI-Standard N°144 / 09.07.2008 / GB BOXER (Deutscher Boxer)

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1 er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ FCI-Standard N°144 / 09.07.2008 / GB BOXER (Deutscher Boxer) 2 TRANSLATION : Mrs C. Seidler, revised by Mrs Sporre-Willes and R. Triquet. Revised by J. Mulholland 2008. ORIGIN : Germany. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE ORIGINAL VALID STANDARD : 01.04.2008. UTILIZATION : Companion, Guard and Working Dog. CLASSIFICATION F.C.I. : Group 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer- Molossoid breeds- Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs. Section 2.1 Molossoid breeds, mastiff type. With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY : The small, so called Brabant Bullenbeisser is regarded as the immediate ancestor of the Boxer. In the past, the breeding of these Bullenbeissers was in the hands of the huntsmen, whom they assisted during the hunt. Their task was to seize the game put up by the hounds and hold it firmly until the huntsman arrived and put an end to the prey. For this job the dog had to have jaws as wide as possible with widely spaced teeth, in order to bite firmly and hold on tightly. A Bullenbeisser which had these characteristics was best suited to this job and was used for breeding. Previously , only the ability to work and utilization were considered. Selective breeding was carried out which produced a dog with a wide muzzle and an upturned nose. GENERAL APPEARANCE : The Boxer is a medium sized, smooth coated, sturdy dog of compact, square build and strong bone. His muscles are taut, strongly developed and moulded in appearance. FCI-St. N° 144 – 09.07.2008 3 His movement is lively, powerful with noble bearing. -

White Markings (Boxers)

White markings By Dan Buchwald White markings have been a very popular yet controversial trait in the Boxer breed. Many favor those dogs with white chests, necks and legs along with the blaze on the face. At the same time, all white Boxers have been a “curse” that breeders have tried to avoid. They are the cause of huge frustration when they appear in big numbers in a litter. It has been an integral part of the breed history the fact that white markings over a third of the total ground color are an unacceptable feature. The AKC standard calls it a disqualification and therefore such animals are not be allowed to compete in conformation rings. A HISTORIC VIEW A quick overview of the history of the breed reveals that Boxers came from an extinct Mastiff-like breed called Brabant Bullenbeisser. Those dogs were originally solid fawns or brindles and, although not very agile, were used for hunting. In order to make them more fit for the job, crosses with the Bulldog ancestor were made and along with physical aptitude came other Bulldog traits such as the white and pied (also known as checks or parti-colors) coats. This is how John Wagner explains the origins of the breed in his book “The Boxer” from 1950: "The literature and paintings previous to 1830 indicate that all Bullenbeisser up to that time were fawn or brindle with black masks. There is never any mention of white. About this time there came a great influx of English dogs to Germany including the English Bulldog. -

Breed-Associated Risks for Developing Canine Lymphoma Differ Among

Comazzi et al. BMC Veterinary Research (2018) 14:232 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1557-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Breed-associated risks for developing canine lymphoma differ among countries: an European canine lymphoma network study Stefano Comazzi1* , Stefano Marelli1, Marzia Cozzi1, Rita Rizzi1, Riccardo Finotello2, Joaquim Henriques3, Josep Pastor4, Frederique Ponce5, Carla Rohrer-Bley6, Barbara C. Rütgen7 and Erik Teske8 Abstract Background: Canine breeds may be considered good animal models for the study of genetic predisposition to cancer, as they represent genetic clusters. From epidemiologic and case collection studies it emerges that some breeds are more likely to develop lymphoma or specific subtypes of lymphoma but available data are variable and geographically inconsistent. This study was born in the context of the European Canine Lymphoma Network with the aim of investigating the breed prevalence of canine lymphoma in different European countries and of investigating possible breed risk of lymphoma overall and/or different lymphoma subtypes. Results: A total of 1529 canine nodal lymphoma cases and 55,529 control cases from 8 European countries/institutions were retrospectively collected. Odds ratios for lymphoma varied among different countries but Doberman, Rottweiler, boxer and Bernese mountain dogs showed a significant predisposition to lymphoma. In particular, boxers tended to develop T-cell lymphomas (either high- or low-grade) while Rottweilers had a high prevalence of B-cell lymphomas. Labradors were not predisposed to lymphoma overall but tended to develop mainly high-grade T-cell lymphomas. In contrast with previous studies outside of Europe, the European golden retriever population did not show any possible predisposition to lymphoma overall or to specific subtypes such as T-zone lymphoma. -

Border Collie

SCRAPS Breed Profile BOXER Stats Country of Origin: Germany Group: Working Use today: Family companion, noise detection, hunting. Life Span: 10 to 12 years Color: Coat colors are fawn and brindle. Fawn shades vary from light tan to mahogany. Coat: Short, shiny, lying smooth and tight to the body. Grooming: The Boxer's smooth, shorthaired coat is easy to groom. Brush with a firm bristle brush, and bathe only when necessary, for it removes the natural oils from the skin. Some Boxers try and keep themselves clean, grooming themselves like a cat. Some cannot resist rolling in another animal’s poop, which calls for a bath. This breed is an average shedder. Height: 21 – 25 inches Weight: 60 – 80 pounds Profile In Brief: One of the breed's most notable black often with white markings. Boxers also characteristics is its desire for human affection, come in a white coat that cannot be registered especially from children. They are patient and with some clubs. spirited with children, but also protective, making them a popular choice for families. The Boxer Temperament: The Boxer is happy, high- requires little grooming, but needs daily spirited, playful, curious and energetic. Highly exercise. intelligent, eager and quick to learn, the Boxer is a good dog for competitive obedience. It is Description: The Boxer's body is compact and constantly on the move and bonds very closely powerful. The head is in proportion with the with the family. Loyal and affectionate, Boxers body. The muzzle is short and blunt with a are known for the way they get along so well distinct stop.