Burundi / Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Burundi

Report No: ACS14147 . Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Burundi Strategies for Urbanization and Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Competitiveness in Burundi . June 19, 2015 . GSURR Public Disclosure Authorized AFRICA . Public Disclosure Authorized Strategies for Urbanization and Economic Competitiveness in Burundi Standard Disclaimer: . This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: . The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

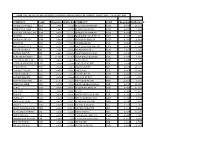

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective Jack Dominic Palmer University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy January 2017 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is their own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Jack Dominic Palmer. The right of Jack Dominic Palmer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Jack Dominic Palmer in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Dr Mark Davis and Dr Tom Campbell. The quality of their guidance, insight and friendship has been a huge source of support and has helped me through tough periods in which my motivation and enthusiasm for the project were tested to their limits. I drew great inspiration from the insightful and constructive critical comments and recommendations of Dr Shirley Tate and Dr Austin Harrington when the thesis was at the upgrade stage, and I am also grateful for generous follow-up discussions with the latter. I am very appreciative of the staff members in SSP with whom I have worked closely in my teaching capacities, as well as of the staff in the office who do such a great job at holding the department together. -

Valūtas Kods Valūtas Nosaukums Vienības Par EUR EUR Par Vienību

Valūtas kods Valūtas nosaukums Vienības par EUR EUR par vienību USD US Dollar 1,185395 0,843601 EUR Euro 1,000000 1,000000 GBP British Pound 0,908506 1,100708 INR Indian Rupee 87,231666 0,011464 AUD Australian Dollar 1,674026 0,597362 CAD Canadian Dollar 1,553944 0,643524 SGD Singapore Dollar 1,606170 0,622599 CHF Swiss Franc 1,072154 0,932702 MYR Malaysian Ringgit 4,913417 0,203524 JPY Japanese Yen 124,400574 0,008039 Chinese Yuan CNY 7,890496 0,126735 Renminbi NZD New Zealand Dollar 1,791828 0,558089 THB Thai Baht 37,020943 0,027012 HUF Hungarian Forint 363,032464 0,002755 AED Emirati Dirham 4,353362 0,229708 HKD Hong Kong Dollar 9,186936 0,108850 MXN Mexican Peso 24,987903 0,040019 ZAR South African Rand 19,467073 0,051369 PHP Philippine Peso 57,599396 0,017361 SEK Swedish Krona 10,351009 0,096609 IDR Indonesian Rupiah 17356,035415 0,000058 SAR Saudi Arabian Riyal 4,445230 0,224960 BRL Brazilian Real 6,644766 0,150494 TRY Turkish Lira 9,286164 0,107687 KES Kenyan Shilling 128,913350 0,007757 KRW South Korean Won 1342,974259 0,000745 EGP Egyptian Pound 18,626384 0,053687 IQD Iraqi Dinar 1413,981158 0,000707 NOK Norwegian Krone 10,925023 0,091533 KWD Kuwaiti Dinar 0,362319 2,759999 RUB Russian Ruble 91,339545 0,010948 DKK Danish Krone 7,442917 0,134356 PKR Pakistani Rupee 192,176964 0,005204 ILS Israeli Shekel 4,009399 0,249414 PLN Polish Zloty 4,576445 0,218510 QAR Qatari Riyal 4,314837 0,231758 XAU Gold Ounce 0,000618 1618,929841 OMR Omani Rial 0,455784 2,194020 COP Colombian Peso 4533,946955 0,000221 CLP Chilean Peso 931,726512 0,001073 -

Central Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency (Ttfa)

Multi-year Expert Meeting on Transport,Trade Logistics and Trade Facilitation: Transport and logistics innovation towards the review of the Almaty Programme of Action in 2014 22-24 October 2013 CENTRAL CORRIDOR TRANSIT TRANSPORT FACILITATION AGENCY (TTFA) by Ms. Rukia D. Shamte Executive Secretary Central Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency (CCTTFA), Dar es Salaam, Tanzania This expert paper is reproduced by the UNCTAD secretariat in the form and language in which it has been received. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the United Nations. 11/4/2013 CENTRAL CORRIDOR TRANSIT TRANSPORT FACILITATION AGENCY (TTFA) MMulti-MultiultiMulti---YearYear Expert Meeting on Transport, Trade Logistics and Trade Facilitation ---1st Session PPalaisalais des Nations ---Room XXVI ---GenevaGenevaGeneva Geneva, 2222----2424 October 2013 CCTTFA – Rukia Shamte Executive Secretary 4/4/2013 1 Introduction • About the TTFA • Introduction • The Institutional Framework • Scope of the TTFA • Objectives • TTFA Objectives • Organs of the TTFA • TTFA Vision and Mission Statement • The Port of Dar es Salaam & the Central Corridor • Major Challenges at the Central Corridor • Trade Facilitation Initiatives along the Central Corridor 4-Nov-13 2 1 11/4/2013 The TTFA-Introduction •The TTFA is a cooperation of Stakeholders and Governments of Burundi, DRC, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda to promote efficient transit transport systems in the interest of all contracting parties. with a view to make the Central Corridor the most cost- effective to enhance the TTFA countries competitiveness in the global market. •The TTFA was formed in recognition of the need & right of landlocked countries (LLC) to transit trade •The TTFA Agreement underlines the modalities of this cooperation. -

Country, Capital, Currency

List of all Countries, Capitals & Currencies of the World Country Capital Currency Afghanistan Kabul Afghan afghani Albania Tirana Albanian lek Algeria Agiers Algerian dinar Andorra Andorra la Vella Euro Angola Luanda Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda St. John’s East Caribbean dollar Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine peso Armenia Yerevan Armenian dram Australia Canberra Australian dollar Austria Vienna Euro Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Nassau Bahamian dollar Bahrain Manama Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi taka Barbados Bridgetown Barbadian dollar Belarus Minsk Belarusian ruble Belgium Brussels Euro Belize Belmopan Belize dollar Benin Porto-Novo (official) West African CFA franc Bhutan Thimpu Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Sucre Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Gaborone Pula Brazil Brasília Brazilian real Brunei Bandar Seri Begawan Brunei dollar Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso Ouagadougou West African CFA franc Burundi Bujumbura Burundian franc Cambodia Phnom Penh Cambodian riel Cameroon Yaoundé Central African CFA franc Canada Ottawa Canadian dollar Cape Verde Praia Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Bangui Central African CFA franc Chad N’Djamena Central African CFA franc Chile Santiago Chilean peso China Beijing Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Bogotá Colombian peso Comoros Moroni Comorian franc Costa Rica San José Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Yamoussoukro (official),Abidjan West African CFA franc (seat of government) Croatia -

ZIMRA Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for Period 24 Dec 2020 To

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 24 DEC 2020 - 13 JAN 2021 ZWL CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATECURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 7.9981 0.1250 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 0.0497 20.1410 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 1.0092 0.9909 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 0.4819 2.0753 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 0.0162 61.7367 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 0.8994 1.1119 AUSTRIA EUR 0.0100 99.6612 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 0.9115 1.0972 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.0046 217.5176 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 0.1792 5.5819 BELGIUM EUR 0.0100 99.6612 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.0100 99.6612 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 0.1322 7.5356 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 0.0173 57.6680 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 0.0631 15.8604 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 4.7885 0.2088 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.0091 109.5983 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 11.0048 0.0909 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 23.8027 0.0420 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 0.1068 9.3633 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 0.0158 63.4921 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.0047 212.7090 CHINESE RENMINBI YUANCNY 0.0800 12.5000 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 1.9648 0.5090 CUBAN PESO CUP 0.3240 3.0863 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 0.0452 22.1111 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 PORTUGAL EUR 0.0100 99.6612 CZECH KORUNA CZK 0.2641 3.7860 QATARI RIYAL QAR 0.0445 22.4688 DANISH KRONER DKK 0.0746 13.4048 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 0.9287 1.0768 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 0.1916 5.2192 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 12.0004 0.0833 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 0.4792 2.0868 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 0.0459 21.8098 EURO EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 0.0163 61.2728 FINLAND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SPAIN EUR 0.0100 99.6612 FRANCE EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 0.1792 5.5819 GERMANY EUR 0.0100 99.6612 -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 08 to 14 July

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 08 TO 14 JULY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 650.4178 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1598 0.2404 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 95.9150 0.0104 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 42.8000 0.0234 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.3329 0.7503 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.9490 0.1117 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8454 1.1829 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 63.9250 0.0156 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.3346 0.0698 BELGIUM EUR 0.8454 1.1829 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8454 1.1829 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.9709 0.0912 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.4232 0.7027 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.1970 0.1924 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 410.9200 0.0024 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7241 1.3810 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0228 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1983.5620 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.7064 0.1149 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2459 0.8026 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4690 0.1546 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 158.3558 0.0063 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.0957 0.0415 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.8154 0.2621 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8454 1.1829 CZECH KORUNA CZK 21.6920 0.0461 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.2866 0.1591 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.2305 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6900 0.0637 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 1001.5019 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 43.9164 0.0228 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3478 0.7419 FINLAND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SPAIN EUR 0.8454 1.1829 FRANCE EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.3346 0.0698 GERMANY -

1 Isiah Brandt Sumner-Fredericksburg High School Sumner, IA Burundi, Factor 20

Isiah Brandt Sumner-Fredericksburg High School Sumner, IA Burundi, Factor 20: Farm to Market Burundi: Building roads for produce to be transported “Now, 50 years after the beginning of the Green Revolution, we again need Dr. Borlaug’s legacy and leadership. For in the coming decades we must confront the single greatest challenge in all human history: whether we can sustainably feed the more than 9 billion people who will be on our planet by the year 2050. Greater than going to the moon; greater than preventing nuclear war; greater than curing cancer, I would argue it is the most difficult issue we've ever confronted." -World Food Prize President Ambassador Kenneth Quinn Why are people hungry today? In a time of prosperity, why are people hungry? The technology and information are available to have a very efficient and prosperous world, but people are still hungry. How can we utilize what we have to prevent poverty? Why aren’t we? There are barriers. The barriers must be knocked down. People are preventing themselves from having a prosperous country by putting up barriers for themselves. This is what Burundi’s government has done for its people. A lot of the barriers were not formed for what they are currently doing, but the government has done very little to remove them. They know about them, but why is nothing still being done? Is there an answer? Do they know the question? From my prospective, the question is; why are people still hungry? Steps may be taken to solve the problem or question. -

Download the PDF File

The following are just some guidelines and recommendations for Tourism in Burundi. I. Travel Frequently-Asked-Questions What to bring? Mosquito repellent, medications, first-aid kit. Travel documents? Passport and visa required. How to get there? No direct flights from U.S.; connections through Brussels, London, Rome, Paris, Addis Abbas, Nairobi, Kampala, and Kigali on the following carriers: Ethiopian Airlines, Kenya Airways, and Air Burundi. Customs? No currency restrictions. How to get around? Buses, vans (cars) and trucks to Kigali, Democratic Republic of Congo and Dar-es-Salaam Driver's license? International Driving Permit. Language? Kirundi, French, Swahili Food and drink? Lunch and dinner are main meals. Sauces (fish, chicken, beef, etc.) with beans, vegetables, potatoes, banana, rice and fufu. Water, juices, beer, wine, liquor, and soft drinks. Tipping? Required but no set up percentage. Customer uses his/her own judgment Weather? Mild temperatures during the day, cooler evenings. Clothes? Lightweight clothes. Sweater in the evening. Electricity? 220 volts. Plugs have 2 round prongs as in Europe. Money? BuFrs 1100=US$1; credit cards rarely accepted, but cash may be withdrawn with card at certain banks. Travellers' checks cashed at local banks. Phone service? International calls from the "Office National des Telecommunications" (0NATEL), hotels and phone centers. Post Office and mail? Office Nationale de la Poste. BuFrs 600/letter. Business hours? Offices: 7:30-12:00, 2:00-5:00 PM, Monday through Friday Banks: 7:30 AM - 12:00 PM, 2:00-5:00 PM, Monday through Friday (some banks open Saturday morning) Shopping hours: 7:30 AM - 7:00 PM, Monday through Saturday Safety? If you want to know the security situation prevailing in Burundi, contact your embassy in Bujumbura or the United Nations representations in Bujumbura. -

Prospects for a Monetary Union in the East Africa Community: Some Empirical Evidence

Department of Economics and Finance Working Paper No. 18-04 , Guglielmo Maria Caporale, Hector Carcel Luis Gil-Alana Prospects for A Monetary Union in the East Africa Community: Some Empirical Evidence May 2018 Economics and Finance Working Paper Series Paper Working Finance and Economics http://www.brunel.ac.uk/economics PROSPECTS FOR A MONETARY UNION IN THE EAST AFRICA COMMUNITY: SOME EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Guglielmo Maria Caporale Brunel University London Hector Carcel Bank of Lithuania Luis Gil-Alana University of Navarra May 2018 Abstract This paper examines G-PPP and business cycle synchronization in the East Africa Community with the aim of assessing the prospects for a monetary union. The univariate fractional integration analysis shows that the individual series exhibit unit roots and are highly persistent. The fractional bivariate cointegration tests (see Marinucci and Robinson, 2001) suggest that there exist bivariate fractional cointegrating relationships between the exchange rate of the Tanzanian shilling and those of the other EAC countries, and also between the exchange rates of the Rwandan franc, the Burundian franc and the Ugandan shilling. The FCVAR results (see Johansen and Nielsen, 2012) imply the existence of a single cointegrating relationship between the exchange rates of the EAC countries. On the whole, there is evidence in favour of G-PPP. In addition, there appears to be a high degree of business cycle synchronization between these economies. On both grounds, one can argue that a monetary union should be feasible. JEL Classification: C22, C32, F33 Keywords: East Africa Community, monetary union, optimal currency areas, fractional integration and cointegration, business cycle synchronization, Hodrick-Prescott filter Corresponding author: Professor Guglielmo Maria Caporale, Department of Economics and Finance, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, Middlesex UB8 3PH, UK. -

2.2.1 Burundi Bujumbura International Airport

2.2.1 Burundi Bujumbura International Airport Airport Overview Passenger Flights Cargo Description and Contacts of Key Companies Runways Helipads Airport Infrastructure Details Passenger and Cargo Performance Indicator Storage Facilities Airfield Costs Fuel Services Charges Cargo Terminal Charges Air-bridge Charges Security Airport Overview Bujumbura’s International Airport Melchior Ndadaye is situated in the western part of the city at about 12 km from the downtown city. The airport is made of asphalt, with a runway’s length of 3 600 m (11 811 ft) equipped with navigation aids and can hold all types of aircraft. The largest aircraft currently operating to/from Bujumbura is a Boeing 777. As of December 2018, the following airlines have regular scheduled service to Bujumbura International Airport. Passenger Flights There are eight airlines serving the Melchior Ndadaye International Airport: Ethiopian Airlines: to Europe, Asia, Africa North America (Washington D.C. & Toronto Pearson) via Addis-Ababa. Air Burundi: serving the Great Lake Region (Entebbe, Kilimanjaro & Kigali). Kenya Airways: to Europe, Asia & Africa via Nairobi. Interlink Airlines: Cape Town & Kruger National Park via Johannesburg. Jeddah (KSA), RwandAir: to Kenya (Nairobi), Uganda (Entebbe), Tanzania (Kilimanjaro, Dar es Salaam), Zambia (Lusaka) South Africa (Johannesburg) via Kigali. Brussels Airlines: Africa, Europe, Asia, North & Latin America via Brussels. Air Tanzania: to/from Dar es Salaam Uganda Airlines: to/from Entebbe International Airport Cargo BruCargo Airfreight link Ethiopian Airlines Cargo link The surface, strength and general condition of the parking area are good. There is enough lighting and the markings are clear. Expansion and runway rehabilitation work has been undertaken and the taxiing and parking areas can accommodate up to 5 large aircraft and 10 smaller aircraft.