This Is an Author Produced Version of a Paper Published in Social Identities : Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dal Flyer South Africalow

SOUTH AFRICA FCL Service DEUTSCHE AFRIKA-LINIEN Weekly direct FCL service from London Gateway Transit Times Cape Town – 24 days London Gateway Port Elizabeth – 26 days Bremerhaven Durban – 28 days Rotterdam Cross border and inland destinations available for: Swaziland Zimbabwe Zambia Nambia Botswana Malawi Lesotho Gaborone Mozambique London Gateway Rotterdam Nacala Beira Walvis Bay Luderitz Maputo Cape Town Durban Port Elizabeth Cape East London Town Port Elizabeth Durban For all your shipping requirements Contact Cory Brothers Shipping Agency Ltd. as agents for DAL. Bob Baxter T: +44 (0)1394 601142 E: [email protected] W: www.cory.co.uk CANARY ISLANDS FCL Service DEUTSCHE AFRIKA-LINIEN DAL meeting the needs of our customers. Canary Islands Weekly direct FCL service. Sailing from Tilbury. Tenerife – 5 days. Las Palmas – 6 days. Lanzarote _ 12 days Tilbury Fuerteventura - 12 days La Palma - 14 days *weekly transit via Las Palmas Tilbury Fuerteventura La Palma La Palma Lanzarote Fuerteventura Tenerife Las Palmas Las Palmas Lanzarote Tenerife For all your shipping requirements Contact Cory Brothers Shipping Agency Ltd. as agents for DAL. Bob Baxter T: +44 (0)1394 601142 E: [email protected] W: www.cory.co.uk INDIAN OCEAN FCL Service DEUTSCHE AFRIKA-LINIEN Indian Ocean Islands Weekly FCL service from Felixstowe via Giaio Tauro** Felixstowe Transit Times La Reunion – (Pointe Des Galets) 30 days. Mauritius – (Port Louis) 32 days. Tamatave (Toamasina) - 36 days. Giaio Tauro** **Transhipment only Felixstowe Giaio Tauro** La Reunion Mauritius Tamatave Port Louis Pointe Des Galets Madagascar For all your shipping requirements Contact Cory Brothers Shipping Agency Ltd. as agents for DAL. -

Evaluating Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Gaborone Dam Catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 Using GIS and Remote Sensing

sustainability Article Evaluating Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Gaborone Dam Catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 Using GIS and Remote Sensing Botlhe Matlhodi 1,* , Piet K. Kenabatho 1 , Bhagabat P. Parida 2 and Joyce G. Maphanyane 1 1 Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Science, University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 00704 Gaborone, Botswana; [email protected] (P.K.K.); [email protected] (J.G.M.) 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 0061 Gaborone, Botswana; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +267-355-5475 Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 7 August 2019; Published: 20 September 2019 Abstract: Land use land cover (LULC) change is one of the major driving forces of global environmental change in many developing countries. In this study, LULC changes were evaluated in the Gaborone dam catchment in Botswana between 1984 and 2015. The catchment is a major source of water supply to Gaborone city and its surrounding areas. The study employed Remote Sensing and Geographical Information System (GIS) using Landsat imagery of 1984, 1995, 2005 and 2015. Image classification for each of these imageries was done through supervised classification using the Maximum Likelihood Classifier. Six major LULC categories, cropland, bare land, shrub land, built-up area, tree savanna and water bodies, were identified in the catchment. It was observed that shrub land and tree savanna were the major LULC categories between 1984 and 2005 while shrub land and cropland dominated the catchment area in 2015. The rates of change were generally faster in the 1995–2005 and 2005–2015 periods. -

The Collaborative African Genomics Network (Cafgen)

AAS Open Research AAS Open Research 2018, 1:3 Last updated: 18 FEB 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE The Collaborative African Genomics Network (CAfGEN): Applying Genomic technologies to probe host factors important to the progression of HIV and HIV-tuberculosis infection in sub-Saharan Africa [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Gerald Mboowa 1,2, Savannah Mwesigwa 1,2, Eric Katagirya1,2, Gaone Retshabile 3, Busisiwe C. Mlotshwa3, Lesedi Williams3, Adeodata Kekitiinwa4, David Kateete 1,2, Eddie Wampande1,2,5, Misaki Wayengera1,2, Betty Nsangi Kintu 4, Grace P. Kisitu4, Samuel Kyobe 2, Chester W. Brown6-8, Neil A. Hanchard9-11, Graeme Mardon9,12, Moses Joloba1,2, Gabriel Anabwani13,14, Ed Pettitt 13, Masego Tsimako-Johnstone3, Ishmael Kasvosve15, Koketso Maplanka 3, Sununguko W. Mpoloka 3, Makhosazana Hlatshwayo14, Mogomotsi Matshaba 13,16 1Department of Immunology and Molecular Biology, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 2Department of Medical Microbiology, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 3Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana 4Baylor College of Medicine Children's Foundation-Uganda, Kampala, Uganda 5Department of Bio-molecular Resources, College of Veterinary Medicine, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 6Genetics Division, Department of Pediatrics , University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA 7Le Bonheur Children's Hospital, Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA 8St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, -

First Chicks to Fly to St Helena, Now Released from Quarantine

www.sams.sh THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. SENT5th NOV NEL Vol. 7, Issue 31 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 01 November 2018 First Chicks to Fly to St Helena, Now Released from Quarantine ... page 7 Record Number of Containers on Wharf Also Inside... ... page 4 Supreme Court Update ... page 5 Cruise Ship Season Begins ... page 9 Team St Helena: International ... page 9 Cricket £100k for National Trust Marine Team ... page 31 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 01 November 2018 | THE SENTINEL THE SENTINEL | Thursday 01 November 2018 www.sams.sh 3 OPINION YOUR LETTERS YOUR LETTERS Thank You question the practical integrity of committed to supporting St Helena to red timber that is much sought Shirley Caroline Benjamin that ambitious statement. For some form direct links with international after elsewhere in the world for very SENTINEL 05/05/1940 – 17/10/2018 unknown reason the United Kingdom organisations and other countries strong and long lasting structures, stopped providing St Helena with in the wider world to strengthen for furniture (indoors and out), and The husband, daughter and son of a funded capital programme. The our society and economy. Indeed, for splendid flooring. COMMENT the late Shirley Benjamin together absence of a capital programme has the United Kingdom encourages St For St.Helena, its’ phenomenal Cyril (Ferdie) Gunnell, SAMS with their families would like to had a serious detrimental impact Helena to pursue direct links with growth in suitable locations and express their sincere thanks to the THE CONSTITUENT on our community. The United countries of the United Nations, and its’ excellent resistance to termites Recently the Governor, Lisa Honan, doctors, nurses and staff of the Kingdom was only able to provide St describes the strengthening of such are added bonuses. -

B Oosting E Conom Ic G Row Th in a Frica Through Infrastructure D Evelopm

Boosting Economic Growth in Africa through Infrastructure Development : Japan’s TICAD and G8 plans Koro Bessho Director-General, International Cooperation Bureau, MOFA, Japan ① Major Economic Corridors in Africa TAH: Trans African Highway #14 EthiopiaEthiopia----SudanSudan Tunisia Corridor #1 AgadirAgadir----CairoCairo Development Morocco (((TATATAHTA HHH:Cairo:Cairo:Cairo----GaboroneGaborone Corridor AGADIR CorridorCorridor)))) CAIRO Algeria Libya Egypt #2 TAH : Dakar ---NNN’N’’’djamenadjamena #15 Northern Corridor Corridor (TAH : LagosLagos----MombasaMombasa Western Corridor) Sahara #3 SenegalSenegal----MauritaniaMauritania Mauritania #16 TAH: CairoCairo----GaboroneGaborone Corridor Mali Niger Chad KHARTOUM Eritrea Corridor DAKAR Senegal N’DJAMENA Sudan #4 Takoradi Development Guinea Gambia Djibouti Burkina Faso Corridor Bissau Guinea Benin Nigeria ADDIS ABABA #17 Central Corridor Togo Ethiopia #5 TAH : Dakar –––Lagos Sierra Leone Ghana Central African R. Cote Corridor Liberia D’Ivoire LAGOS Somalia Cameroon #18 Tazara Corridor TAKORADI Uganda #6 TAH : LagosLagos----MombasaMombasa Kenya Corridor Rep. Gabon Congo Rwanda D.R. MOMBASA #19 Mtwara Corridor #7 TAH: TripoliTripoli----WindhoekWindhoek Congo Burundi Corridor Tanzania DAR ES SALAAM LUANDA #8 Malange Corridor MTWARA LOBITO Malawi #20 Nacala Corridor Angola Zambia #9 Lobito Corridor NAMIBE LUSAKA NACALA HARARE #10 Namibe Corridor Zimbabwe Namibia BEIRA #21 Madagascar SDI Botswana Mauritius WALVIS BAY Mozambique Madagascar #11 TransTrans----CCCCapriviaprivi Corridor WINDHOEK Swaziland -

An Analysis of Alcohol and Cigarette Prices in Maseru, Gaborone, and Neighboring South African Towns

: TRADE A GLOBAL REVIEW OF COUNTRY EXPERIENCES BOTSWANA, LESOTHO, AND SOUTH AFRICA: AN ANALYSIS OF ALCOHOL AND CIGARETTE PRICES IN MASERU, GABORONE, AND NEIGHBORING SOUTH AFRICAN TOWNS TECHNICAL REPORT OF THE WORLD BANK GROUP GLOBAL TOBACCO CONTROL PROGRAM. CONFRONTING EDITOR: SHEILA DUTTA ILLICIT TOBACCO BOTSWANA, LESOTHO, AND SOUTH AFRICA 19 BOTSWANA, LESOTHO, AND SOUTH AFRICA An Analysis of Alcohol and Cigarette Prices in Maseru, Gaborone, and Neighboring South African Towns Kirsten van der Zee and Corné van Walbeek1 Chapter Summary The government of Lesotho plans to implement a levy on tobacco and alcohol products. The proposed measure is similar to levies that have been implemented in Botswana in recent years. A concern is the possibility that Lesotho’s new levy may stimulate a significant increase in bootlegging between Lesotho and South Africa. This chapter investigates the presence and possibility of bootlegging between South Africa and Botswana, and South Africa and Lesotho, by describing the differences in cigarette and alcohol prices between Gaborone, Botswana, and the nearby South African towns of Mafikeng and Zeerust, as well as between Maseru, Lesotho, and nearby Ladybrand, South Africa. 1 Economics of Tobacco Control Project, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 551 551 Confronting Illicit Tobacco Trade: A Global Review of Country Experiences An analysis of comparative cigarette price data indicated the following: Gaborone and Mafikeng/Zeerust. Overall, average cigarette prices are significantly higher in Gaborone than in nearby South African towns. The cheapest pack price found in Gaborone was nearly five times the cheapest price identified in South Africa. Maseru and Ladybrand. Cigarette prices differ between Maseru and Ladybrand, but much less than between Gaborone and Mafikeng/Zeerust. -

INF Congress Welcome Brochure 2017

INF CONGRESS 2017 INTERNATIONAL NETBALL FEDERATION WELCOME BROCHURE About Botswana & Gaborone The Host City Botswana is centrally located in the heart of Southern Africa. It shares borders with Zambia in the north, Namibia in the north and northwest, Zimbabwe in the northeast and South Africa in the south. Gaborone is the Capital City of Botswana. What makes Gaborone so unique is that the visitor can enjoy all the familiar modern conveniences of home, but can gain entry into rural Africa, or wildlife areas, within minutes – having then the best of both possible worlds. Languages English is the official language and Setswana, the national language, is the most widely spoken conversational language in Botswana. Weather Typical Average High and Low Temperature in July During the month of July the weather in Botswana is usually dry with cool temperatures in the morning and evening. The daytime averages are between 16C and 23C. Currency The Pula (BWP) is the currency of Botswana. As of December 2016 the Botswana Pula was equivalent to: - US Dollar 0.094673 - Euro 0.088028 - British Pound 0.075168 - Australian Dollar 0.125106 - Singapore Dollar 0.133128 - Malaysian Ringgit 0.414891 Please Note: Botswana Pula can only be obtained in Botswana and South Africa. The US Dollar is used in some hotels. Visa card can generally be used in hotels and major retail outlets. Tourism Botswana is well known for having some of the best wilderness and wildlife areas on the African continent. A full 38% of its total land area is devoted to national parks, reserves and wildlife management areas – for the most part unfenced, allowing animals to roam wild and free. -

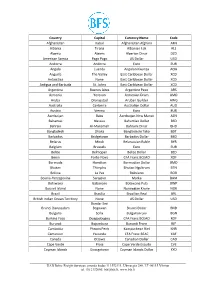

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Supplementary Material Barriers and Facilitators to Pre-Exposure

Sexual Health, 2021, 18, 130–39 © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Supplementary Material Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis among A frican migr ants in high income countries: a systematic review Chido MwatururaA,B,H, Michael TraegerC,D, Christopher LemohE, Mark StooveC,D, Brian PriceA, Alison CoelhoF, Masha MikolaF, Kathleen E. RyanA,D and Edwina WrightA,D,G ADepartment of Infectious Diseases, The Alfred and Central Clinical School, Monash Un iversity, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. BMelbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. CSchool of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. DBurnet Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. EMonash Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Vi, Auc. stralia. FCentre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. GPeter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. HCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] File S1 Appendix 1: Syntax Usedr Dat fo abase Searches Appendix 2: Table of Excluded Studies ( n=58) and Reasons for Exclusion Appendix 3: Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Studies Using the ‘ Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies’ (39) Appendix 4: Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies U sing a modified ‘CASP Qualitative C hecklist’ (37) Appendix 5: List of Abbreviations Sexual Health © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Appendix 1: Syntax Used for Database -

Trans African Highway

●:T/A ☆:Grant As of December 20, 2007 ★:Loans Major Economic Corridor and Japan’s Assistance ():Candidate Projects Red-Color:Incl. Japan’s Assistance *Only on-going/candidate projects TAH: Trans African Highway are shown on this sheet Tunisia #14 Ethiopia-Sudan Corridor #1 Agadir-Cairo Development Corridor (TAH:Cairo-Gaborone Corridor) ★Mediterranean Road Construction Morocco ☆Rehabilitation of Trunk Road (I- #2 Niger Development Corridor III) Algeria Libya ★Road Improvement and Transport Egypt Program on the Southbound Bamako- Dakar Corridor #15 Northern Corridor ☆Construction of Bridges on the Western (TAH : Lagos-Mombasa Corridor) Mali/Senegal South Corridor Sahara (★)Mombasa Ports Development Project (#3 Senegal-Mauritania Corridor) (★)Rosso Bridge Mauritania (●、★)Jinja/Nile Bridge (Uganda) Mali Niger Chad Eritrea #4 Takoradi Development Corridor #16 TAH: Cairo-Gaborone Sudan (☆)Anwiankwanta-Yamoransa Road Senegal Corridor Gambia Djibouti Rehabilitation Project (Ghana) Guinea ★Arusha-Namanga-Athi river Burkina Faso (●)OSBP at Paga Bissau Guinea Road Development Project Nigeria Benin ●OSBP at Namanga Togo Ethiopia #5 Lagos –Abidjan Corridor Sierra Leone Central Ghana #17 Central Corridor (☆) African R. Kasoa-Yamoransa Road Cote D’Ivoire Rehabilitation Project (Ghana) Liberia Cameroon Somalia #18 Tazara Corridor #6 TAH : Lagos-Mombasa Corridor Uganda Kenya #19 Mtwara Corridor (★)Ekok-Mamfe Road Project Rep. ☆Masasi-Mangaka Road (Cameroon) Gabon Congo ●OSBP (Paga) Rwanda Rehabilitation Project D.R. (★)Mangaka-Tunduru Road #7 TAH: Tripoli-Windhoek -

American Friends Service Committee International Division Southern Africa International Affairs Report

AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE INTERNATIONAL DIVISION SOUTHERN AFRICA INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REPORT June 22, 1983 . Lett.e,r' No'\ ,2 from Ted Lockwood Dear Friends, I've spent the last two months exploring homes bases: Harare, the one I have tentatively selected, and Gaborone, the one that Maghan-:-:suggested. I've tried to settle in but 'I can't say that I have succeeded in being more than a visitor. But even a visitor has certain first impressions that may have a certain superficial or even lasting validity. First Impressions Harare and Gaborone are both capital cities. Both are'bustlingcomme~cial centers with a wealth of consumer goods hard to find in Lusaka, Dar es Salaam or Luanda. Harare is bustling, big, strenuous, rumor-ridden. Harare is Ii churn, a cock pit of politics. ItVs easy to feel the clash of nationalist politician& striving to consolidate power, striving to gain it or not lose it. The racists are leaving but not without a sour or defiant or limp complaint. Some are staying and get fined or jailed for their language~ The old order is changing but the new one has not yet been fully born. Skills are departing; untried new blood is eager io fill the place. Harare is ~ssessing its directiori for the future, but.is unsure of its identity. It's proudly African but parliament opens with British-style pomp and circumstance. Black boys and girls wi"th boaters and blazers with seals mingle equally with their white counterparts. Workers in stores wear proper.,t'ies and say Madam and Sir. -

Preliminary Checklist of the Plants of Botswana

PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF THE PLANTS OF BOTSWANA PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF THE PLANTS OF BOTSWANA by Moff at P. Setshogo Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 37 n 2005 Recommended citation format SETSHOGO, M.P. 2005. Preliminary checklist of the plants of Botswana. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 37. SABONET, Pretoria and Gaborone. Produced by University of Botswana Herbarium Private Bag UB00704 Gaborone Botswana Tel. (267) 355 2602 Fax: (267) 318 5097 Published by Southern African Botanical Diversity Network (SABONET) c/o South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X101, 0001, Pretoria, South Africa and University of Botswana Herbarium, Private Bag UB00704, Gaborone. Printed in 2005 in the Republic of South Africa by Capture Press, Pretoria, (27) 12 349-1802. ISBN 1-919976-18-3 © 2005 SABONET. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Editor-in-chief: Marthina Mössmer Subeditors: Lidia Gibson, Hanlie van Heerden & Cecilia de Vos Belgraver Text design and layout: Nicola Ellis (27) 82 878 9589 Cover design: Antoinette Burkhardt, Pretoria, South Africa (27) 82 909 0109 Photographs: M.P. Setshogo SABONET website: www.sabonet.org This report is a joint product of the University of Botswana Herbarium and the Southern African Botanical Diversity Network (SABONET) and was made possible through support provided by the Global Environment Facility (GEF)/ United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/World Conservation Union-Regional Office for southern Africa (IUCN ROSA) (Plot no.