Vancouver Park Board Has Established the Original Planting Scheme, Including a Number of Tree Species Referenced in Shakespeare’S Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Aboriginal Awareness Week Booklet

National Aboriginal Awareness Week 2016 May 19–22 Aboriginal Awareness This week of celebration is an opportunity for all Canadians, especially young people and educators, who have the opportunity to create a Shared Teachings/Learnings environment to learn more about Aboriginal cultural heritages of Canada. By sharing our knowledge and experience, there will be greater understanding and harmony among all Canadians. In recognition of the many aboriginal cultures and experiential difference that exist among the BC and Canadian aboriginals, the Shared Teachings/Learnings suggested in this booklet are intended to highlight Aboriginal peoples, events, places, issues and realities that are statement of knowledge about Aboriginal peoples’ cultures, values, beliefs, traditions, history and languages. Source(s) Shared Learning: Integrating BC Aboriginal Content K–10 Did you know? Did you know that some of BC’s towns or cities have names that come from aboriginal sources. Find out what the following names mean and from which language the words come from. Match the names with the description. Chilliwack The name comes from an Okanagan word meaning “the always place”, in the sense of a permanent dwelling place. Coquitlam Is the name of the local tribe, ch.ihl-KWAY-uhk. This word is generally interpreted to mean “going back up”. Kamloops Is likely from the Salish tribal name which is translated as “small red salmon”. The name refers to the sockeye salmon common to the area. Suggestion: Make up your own matching work list or create a word search, etc. Place names reveal Aboriginal peoples’ contributions: Place names are never just meaningless sounds. -

Bibliography of British Columbia1

Bibliography of British Columbia1 Compiled by Eve Szabo, Senior Librarian, Social Sciences Division, W. A. G. Bennett Library, Simon Fraser University. Books ALBERNI DISTRICT MUSEUM AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Place names of (he Alberni Valley. Supplement 1982. Port Alberni, B.C., 1982. 15 p. ALLEN, Richard Edward. Heritage Vancouver: a pictorial history of Van couver. Book 2. Winnipeg, Josten's Publications, 1983. 100 p. $22.95. ANDERSON, Charles P. and others, editors. Circle of voices: a history of the religious communities of British Columbia. Lantzville, B.C., Oolichan Books, 1983. 288 p. $9.95. BARRETT, Anthony A. and Rhodri Windsor Liscombe. Francis Rattenbury and British Columbia: architecture and challenge in the imperial age. Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1983. 391 p. $29.95. BASQUE, Garnet. Methods of placer mining. Langley, B.C., Sunfire Publi cations, 1983. 127 p. $6.95. (This is also History of the Canadian West special issue, November 1983.) BOWMAN, Phylis. "The city of rainbows [Prince Rupert]!" Prince Rupert, B.C., [the author], 1982. 280 p. $9.95. CONEY, Michael. Forest ranger, ahoy!: the men, the ships, the job. Sidney, B.C., Porthole Press, 1983. 232 p. $24.95. ECKEL, Catherine C. and Michael A. Goldberg. Regulation and deregula tion of the brewing industry: the British Columbia example. Working paper, no. 929. Vancouver, University of British Columbia, Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration, 1983. 53 p. GOULD, Ed. Tut, tut, Victoria! Victoria, Cappis Press, 1983. 181 p. $6.95. HARKER, Byron W. Kamloops real estate: the first 100 years. Kamloops, [the author], 1983. 324 p. $40.00. -

Diary of William a Quantz © Lived 1854 – 1945

Diary of William A Quantz © Lived 1854 – 1945 Volume 6 1920 – 1922 Source and Copy Reference Information While copyright and ownership remains with all direct descendants of William A. Quantz, the family welcomes inquiries from readers about additional usage consistent with the spirit and purposes as stated by the author." You can contact us at [email protected]. Note: Starting with volume 5 the page numbers started at 1 again. Volume 6 starts at page 127. Page 127 1920 - Happy New Year - 1920 A bright new year and a sunny track Along and upward way, And a song of praise on looking back Wednesday year has passed away, And golden sheaves, nor small north you, This is my New Year’s wish for you. January 3:. Last Sunday I went up to the First Christian Church on Bathurst Street, and heard Morton preach. Went home with him for dinner and had a good visit. Monday Flo and I went up to cousin Jake Quantz’s at Edgely. Had another good visit and came back to the city on Wednesday in Joe Quantz’s car with them. New Year’s Day was spent with the girls again and yesterday we came home. Brother Ed is down from Alberta and he brought Minnie Ruth from Wellington’s and I expect they will be with us for some time. January 10:. We are enjoying ourselves at home once more. Ed and Minnie are here and we are doing as much visiting as work. The weather has been cold and it seems to be a cozy place in the bay-window over the register. -

Self-Guiding Geology Tour of Stanley Park

Page 1 of 30 Self-guiding geology tour of Stanley Park Points of geological interest along the sea-wall between Ferguson Point & Prospect Point, Stanley Park, a distance of approximately 2km. (Terms in bold are defined in the glossary) David L. Cook P.Eng; FGAC. Introduction:- Geomorphologically Stanley Park is a type of hill called a cuesta (Figure 1), one of many in the Fraser Valley which would have formed islands when the sea level was higher e.g. 7000 years ago. The surfaces of the cuestas in the Fraser valley slope up to the north 10° to 15° but approximately 40 Mya (which is the convention for “million years ago” not to be confused with Ma which is the convention for “million years”) were part of a flat, eroded peneplain now raised on its north side because of uplift of the Coast Range due to plate tectonics (Eisbacher 1977) (Figure 2). Cuestas form because they have some feature which resists erosion such as a bastion of resistant rock (e.g. volcanic rock in the case of Stanley Park, Sentinel Hill, Little Mountain at Queen Elizabeth Park, Silverdale Hill and Grant Hill or a bed of conglomerate such as Burnaby Mountain). Figure 1: Stanley Park showing its cuesta form with Burnaby Mountain, also a cuesta, in the background. Page 2 of 30 Figure 2: About 40 million years ago the Coast Mountains began to rise from a flat plain (peneplain). The peneplain is now elevated, although somewhat eroded, to about 900 metres above sea level. The average annual rate of uplift over the 40 million years has therefore been approximately 0.02 mm. -

One with Nature

SFU | Laboratory Landscape | proposal Josie Dawson, Phoebe Huang, Lori Lai 1. OVERVIEW One with Nature One with Nature is an interactive installation piece that subverts conventional notions around what “urban wilderness” entails and the dichotomy between nature and city. The piece asks viewers to question the carefully maintained quality of urban green spaces that reFlect humanistic expectations oF what nature should be, resulting in contrived attempts at preservation and romanticization oF normal ecological processes. Through human modification of the space, nature is domesticized. This piece will integrate impermanent and staged interventions at various sites, which will recontextualize Stanley Park as a site For investigation that encourages pedestrians to think deeply about humanistic alterations to, what may seem to be, “The Wilderness”. The rearranging oF preconceived perceptions about Stanley Park will attempt to disrupt typical understandings of our treasured green space and reconnect the public to knowledge and histories that contributed to the park as we know it, today. 2. RESEARCH AND PROCESS During the initial stages oF our proJect, we developed our main topic in attempts to explore the socially constructed aspects oF nature in relation to Stanley Park both as an urban space For recreational leisure and a segregated space oF wilderness conservation and constructed biodiversity. Our research began by identiFying the characteristics oF urban parks, their signiFicance as a public space and Finally our relationship with parks as a site For leisure. In North America, the creation of parks stems from the practice of upholding natural spaces within European landscapes. It's purpose is to be a pleasurable symbol oF taste and wealth but most signiFicantly an essential element For a good quality of liFe. -

2014-2015 Annual Report Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC

2014-2015 Annual Report Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC The Next Phase – Year 3 • July 2015 2 2014-2015 AnnUAL REPOrt Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC 3 Table of Contents About the Aboriginal Tourism Association of British Columbia 4 Chair’s Message 6 CEO’s Message 7 Key Performance Indicators 8 2014 / 15 Financials: The Next Phase –Year 3, Statement of Operations Budget vs. Actual 9 Departmental Overviews Klahowya Village in Stanley Park, Vancouver BC Training & Product Development 10 Marketing 14 Authenticity Programs 22 Aboriginal Travel Services 24 Partnerships and Outreach Activities 27 Gateway Strategy 31 Appendix A: Stakeholder - Push for Market-Readiness 35 Appendix B: Identify & Support Tourism Opportunities 43 The Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC acknowledges the funding contribution from Destination BC, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development and Western Economic Diversification Canada. 4 2014-2015 AnnUAL REPOrt Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC 5 About the Aboriginal Tourism Association Goals Strategic Priorities of British Columbia • Improve awareness of Aboriginal tourism among Aboriginal Our key five-year strategic priorities are: communities and entrepreneurs • Push for Market-Readiness The Aboriginal Tourism Association of British Columbia (AtBC) is a non-profit, Stakeholder-based organization • Support tourism-based development, human resources and • Build and Strengthen Partnerships economic growth and stability in Aboriginal communities that is committed to growing and promoting a sustainable, culturally rich Aboriginal tourism industry. • Focus on Online Marketing • Capitalize on key opportunities, such as festivals and events Through training and development, information resources, networking opportunities and co-operative that will forward the development of Aboriginal cultural • Focus on Key and Emerging marketing programs, AtBC is a one-stop resource for Aboriginal entrepreneurs and communities in British tourism Markets Columbia who are operating or looking to start a tourism business. -

Legacy of Trees Excerpt

l e g a c y o f t r e e s l e g a c y o f t r e e s Purposeful Wandering in Vancouver’s Stanley Park Nina Shoroplova Copyright © 2020 Nina Shoroplova Foreword copyright © 2020 Bill Stephen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, audio recording, or otherwise—without the written permission of the publisher or a licence from Access Copyright, Toronto, Canada. Heritage House Publishing Company Ltd. heritagehouse.ca Cataloguing information available from Library and Archives Canada 978-1-77203-303-8 (PBK) 978-1-77203-304-5 (EBOOK) Edited by Marial Shea Proofread by Grace Yaginuma Index by Martin Gavin Cover, interior book design, and maps by Jacqui Thomas Cover photographs: Andrew Dunlop / iStockphoto.com ( front), zennie / iStockphoto.com (back) Frontipiece photograph: Milan Rademakers / shutterstock.com Interior colour photographs by Nina Shoroplova Interior historical photographs are from the City of Vancouver Archives unless otherwise noted The interior of this book was produced on FSC®-certified, acid-free paper, processed chlorine-free, and printed with vegetable-based inks. Heritage House gratefully acknowledges that the land on which we live and work is within the traditional territories of the Lkwungen (Esquimalt and Songhees), Malahat, Pacheedaht, Scia’new, T’Sou-ke, and WSÁNEĆ (Pauquachin, Tsartlip, Tsawout, and Tseycum) Peoples. We also acknowledge that Stanley Park, the subject of this book, is located on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. -

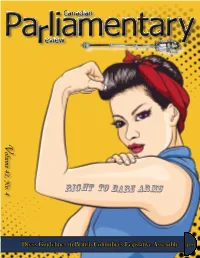

Ar Ba to Rig Re Ht Ms

Canadian eview V olume 42, No. 4 Right to BaRe Arms Dress Guidelines in British Columbia’s Legislative Assembly p. 6 2 CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW/SUMMER 2019 There are many examples of family members sitting in parliaments at the same time. However, the first father-daughter team to sit together in a legislative assembly did not happen in Canada until 1996. That is when Sue Edelman was elected to the 29th Yukon Legislative Assembly, joining her re-elected father, Ivan John “Jack” Cable. Mr. Cable moved to the North in 1970 after obtaining degrees in Chemical Engineering, a Master’s in Business Administration and a Bachelor of Laws in Ontario. He practiced law in Whitehorse for 21 years, and went on to serve as President of the Yukon Chamber of Commerce, President of the Yukon Energy Corporation and Director of the Northern Canada Power Commission. He is also a founding member of the Recycle Organics Together Society and the Boreal Alternate Energy Centre. Mr. Cable’s entry into electoral politics came in 1992, when he successfully won the riding of Riverdale in East Whitehorse to take his seat in the Yukon Legislative Assembly. Ms. Edelman’s political presence had already been established by the time her father began his term as an MLA. In 1988, she became a Whitehorse city councillor, a position she held until 1994. In her 1991 reelection, she received more votes for her council seat than mayor Bill Weigand received. Following her time on city council, she was elected to the Selkirk Elementary School council. In the 1996 territorial election, she ran and won in the Riverdale South riding. -

Deadman's Island S\

VS RWj z i CORRESPONDENCE AND PAPERS IN REFERENCE TO STANLEY PAEK DEADMAN'S ISLAND S\ BRITISH COLUMBIA PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT OTTAWA PRINTED BY S. E. DAWSON, PRINTER TO THE QUEEN'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1899 i RETURN [68a.] To an ADDRESS of the HOUSE of COMMONS, dated 1st May, for copies of all Orders in Council respecting Stanley Park and Deadman's Island, Vancouver, B.C., and all correspondence between the different Departments of the Canadian Government and the Imperial military and naval authorities respecting the park, or island, or both. Also for copies of all correspon dence respecting the same with the Government of British Columbia, the city of Vancouver, and the park authorities. Also for all correspondence between the member for Burrard, the Hon. Minister of Militia and Defence and the Department of Militia, the Hon. Minister of the Interior and other members of the Government, respecting the same. Also for all correspondence between Mr. Ludgate and his represen n tative and any Department of Government respecting Deadman's Island. Also a copy of all applications and correspondence respecting a lease or grant of Deadman's Island. Also a copy of all departmental reports, memoranda or letters on file in the Departments of Justice, Interior, Militia and Defence, respecting the park, Deadman's Island, or the title and disposal of the same ; also a copy of all grants or leases of the park or Deadman's Island. Also all reports or information obtained by the different departments before any lease or grant of Deadman's Island was enacted. -

Tlingit/Haida Material Resources Library Media Services Fairbanks North Star Borough School District

Tlingit/Haida Material Resources Library Media Services Fairbanks North Star Borough School District Media/Call Number Title Author [ Audiobook ] Touching Spirit Bear Mikaelsen, Ben, 1952- [ Book ] A Tlingit uncle and his nephews Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] Chilkoot trail : heritage route to the Klondike Neufeld, David. [ Book ] Illustrated Tlingit legends drawings by Tresham Gregg. [ Book ] Indian primitive Andrews, Ralph W. (Ralph Warren), 1897- 1988. [ Book ] Remembering the past : Haida history and culture Cogo, Robert. [ Book ] Songs of the dream people : chants and images from the Indians Houston, James A., 1921- and Eskimos of North America [ Book ] Songs of the totem Davis, Carol Beery. [ Book ] The native people of Alaska : traditional living in a northern land Langdon, Steve, 1948- [ Book ] The raven and the totem : [traditional Alaska native myths and Smelcer, John E., 1963- tales] [ Book ] The Tlingit way : how to make a canoe Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] The Tlingit way : how to treat salmon. Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] The Tlingit world Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] Three brothers Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] Tlingit Indians of Southeastern Alaska : teacher's guide Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] Tlingit Indians of Southeastern Alaska : teacher's guide. Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] Tlingit Indians of Southeastern Alaska, teacher's guide Partnow, Patricia H. [ Book ] Totem poles to color & cut out Brown, Steven. [ Book ] Touching Spirit Bear Mikaelsen, Ben, 1952- [ Book ] 078.5 LYO Pacific coast Indians of North America Lyons, Grant. [ Book ] 390 CHA Alaska's native peoples Chandonnet, Ann. [ Book ] 398.2 AME 1998 American Indian trickster tales selected and edited by Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz. -

Hop-On Hop-Off

HOP-ON Save on Save on TOURS & Tour Attractions SIGHTSEEING HOP-OFF Bundles Packages Bundle #1 Explore the North Shore Hop-On in Vancouver + • Capilano Suspension Bridge Tour Whistler • Grouse Mountain General Admission* • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass This bundle takes Sea-to-Sky literally! Start by taking in the spectacular ocean You Save views in Vancouver before winding along Adult $137 $30 the Sea-to-Sky Highway and ascending into Child $61 $15 the coastal mountains. 1 DAY #1: 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Your perfect VanDAY #2: Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour* Sea to Bridge Experience You Save • Capilano Suspension Bridge day on Hop-On, Adult $169 $30 • Vancouver Aquarium Child $89 $15 • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass You Save Hop-Off Operates: Dec 1, 2019 - Apr 30, 2020 Classic Pass Adult $118 $30 The classic pass is valid for 48 hours and * Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour operates: Child $53 $15 Choose from 26 stops at world-class • Dec 1, 2019 - Jan 6, 2020, Daily includes both Park and City Routes • Apr 1 - 30, 2020, Daily attractions and landmarks at your • Jan 8 - Mar 29, 2020, Wed, Fri, Sat & Sun 2 own pace with our Hop-On, Hop-Off Hop-On, Hop-Off + WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 - APR 30, 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Sightseeing routes. $49 $25 Lookout Tower Special Adult Child (3-12) Bundle #2 Hop-On in Vancouver + • Vancouver Lookout Highlights Tour Victoria • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass • 26 stops, including 6 stops in Stanley Park CITY Route PARK Route and 1 stop at Granville Island Take an in-depth look at Vancouver at You Save (Blue line) (Green Line) your own pace before journeying to the Adult $53 $15 • Recorded commentary in English, French, Spanish, includes 9 stops includes 17 stops quaint island city of Victoria on a full day of Child $27 $8 German, Japanese, Korean & Mandarin Fully featuring: featuring: exploration. -

A Review of Ethnographic and Historically Recorded Dentaliurn Source Locations

FISHINGFOR IVORYWORMS: A REVIEWOF ETHNOGRAPHICAND HISTORICALLY RECORDEDDENTALIUM SOURCE LOCATIONS Andrew John Barton B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1979 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Q Andrew John Barton 1994 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Burnaby October, 1994 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means without permission of the author. Name: Andrew John Barton Degree: Master of Arts (Archaeology) Title of Thesis: Fishing for Ivory Worms: A Review of Ethnographic and Historically Recorded Dentaliurn Source Locations Examining Committee: Chairperson: Jack D. Nance - -, David V. Burley Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Richard Inglis External Examiner Department of Aboriginal Affairs Government of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of ThesisIDissertation: Fishing for Ivory Worms: A Review of Ethnographic and Historically Recorded Dentalium Source Locations Author: Andrew John Barton Name October 14, 1994 Date This study reviews and examines historic and ethnographic written documents that identify locations where Dentaliurn shells were procured by west coast Native North Americans.