Speech Perception in Individuals with Auditory Neuropathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

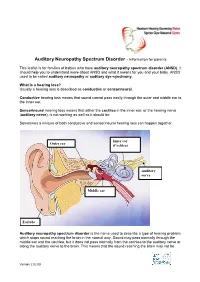

Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder - Information for Parents

Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder - Information for parents This leaflet is for families of babies who have auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD). It should help you to understand more about ANSD and what it means for you and your baby. ANSD used to be called auditory neuropathy or auditory dys-synchrony. What is a hearing loss? Usually a hearing loss is described as conductive or sensorineural. Conductive hearing loss means that sound cannot pass easily through the outer and middle ear to the inner ear. Sensorineural hearing loss means that either the cochlea in the inner ear, or the hearing nerve (auditory nerve), is not working as well as it should be. Sometimes a mixture of both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss can happen together. Inner ear Outer ear (Cochlea) Auditory nerve Middle ear Earlobe Auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder is the name used to describe a type of hearing problem which stops sound reaching the brain in the normal way. Sound may pass normally through the middle ear and the cochlea, but it does not pass normally from the cochlea to the auditory nerve or along the auditory nerve to the brain. This means that the sound reaching the brain may not be Version 2 02.09 understood and the quality may be poor. The results of different hearing tests will help the audiologist (hearing specialist) decide if your baby has ANSD. Testing for ANSD We can carry out tests that show how well the cochlea and auditory nerve are working, even if your baby is very young. If the tests show the cochlea is working well but the auditory nerve is not working as it should be, then ANSD could be the cause. -

Starkey Audiology Series

STARKEY AUDIOLOGY SERIES DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF PEDIATRIC AUDITORY NEUROPATHY Deborah Hayes, Ph.D. Chair, Audiology, Speech Pathology and Language Services The Children’s Hospital - Colorado Auditory neuropathy (AN) is a complex auditory resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of auditory nerve disorder, which results in a distinct pattern of abnormality. For an excellent review of auditory audiometric test results and a wide range of neuropathy, see Yvonne Sininger and Arnold Starr symptoms and auditory complaints. The range of (editors): Auditory Neuropathy A New Perspective functional auditory abilities in individuals with AN on Hearing Disorders. is vast and may include normal hearing sensitivity and limited auditory complaints, fluctuating hearing Although the scientific and professional community sensitivity and difficulty understanding speech, have made significant progress in understanding the especially in noise, or profound hearing loss and nature and variable consequences of AN, optimal inability to understand even amplified speech in clinical management options for individuals with quiet despite evidence of normal cochlear outer hair this disorder remain elusive, especially for infants cell function. and very young children. For infants with “typical” sensory hearing loss who are identified through Early reports of auditory neuropathy described newborn hearing screening, excellent and detailed the paradox of individuals with normal pure-tone guidelines for identification, diagnosis, and early audiograms but absent or severely abnormal intervention are widely accepted (Joint Committee auditory brainstem responses (ABR). In some cases, on Infant Hearing, 2007). These guidelines do not individuals demonstrated pure-tone audiograms with address, however, some of the specific challenges mild to moderately-elevated detection thresholds, in providing families with appropriate management absent/abnormal ABRs, and absent middle options for infants with AN. -

Diagnosis and Management of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum

Understanding Auditory Neuropathy: Diagnosis and Management EHDI: Partnering for Progress Raleigh, NC October 26-28, 2011 Patricia Roush, AuD University of North Carolina School of Medicine Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA University of North Carolina Department of Otolaryngology UNC Hospitals Audiologists: Laura Fleenor McCall, AuD Otolaryngologists: Nissele Franco, AuD Oliver Adunka, MD Corinne Macpherson, AuD Craig Buchman, MD Sarah Martinho, AuD Amelia Drake, MD Patty Reitz, M.S. Austin Rose, MD Jill Ritch, AuD Carlton Zdanski, MD Patricia Roush, AuD Harold Pillsbury, III, MD University of North Carolina Department of Otolaryngology Carolina Children’s Communicative Disorders Program Center for the Acquisition of Spoken Language through Listening Enrichment Audiologists: Debora Hatch, AuD Speech-Language Pathologists: Lisa Park, AuD Hannah Eskridge, AVT Jennifer Woodard, AuD Lillian Henderson, AVT Holly Teagle, AuD Sandra Hancock, AVT Erin Thompson, AVT Maegan Evans, PhD Outline • Overview and Definitions • Protocol for Diagnosis and Management • Case Studies • Implications for Clinical Practice Auditory Neuropathy: A Definition Clinical syndrome characterized by electrophysiological evidence of normal or near normal cochlear function and absent or abnormal auditory pathway transduction Audiologic Findings Ø Normal outer hair cell function as measured by present otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) or the presence of a cochlear microphonic (CM). Ø OAEs may be present initially but disappear over time Ø Abnormal auditory nerve response as observed -

Identification and Management of Infants and Young Children with Consensus

Guidelines for Identification and Management of Infants and Young Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder Guidelines Development Conference at NHS 2008, Como, Italy More Hearing. Slim Design. WaterResistant. Now available: Naída, designed for moderately-severe to profound hearing loss. Restoration of high frequency audibility and uncompromised performance. Get the power to change life, now for all degrees of significant hearing loss. www.naida.phonak.com Guidelines for Identification and Management of Infants and Young Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder Co-Chairs Deborah Hayes, PhD Co-Chair, Bill Daniels Center for Children’s Hearing Kelley Family/Schlessman Family Scottish Rite Masons Chair in Childhood Language Disorders The Children’s Hospital – Colorado Yvonne S. Sininger, PhD Professor, Head and Neck Surgery David Geffen School of Medicine University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, California Editor Jerry Northern, PhD Professor Emeritus University of Colorado School of Medicine Colorado Hearing Foundation Denver, Colorado Conference and Editorial Assistant Valerie Hernandez Program Assistant Bill Daniels Center for Children’s Hearing The Children’s Hospital – Colorado This monograph is sponsored in part by a generous grant from the Kelley Family/Schlessman Family Scottish Rite Masons Chair in Childhood Language Disorders The Children’s Hospital – Colorado ©2008 The Children’s Hospital – Colorado, Aurora, Colorado USA. All Rights Reserved. The ONLYONLY handheld OAE-Tympanometry combination system... Audiologists Physicians Birth-to-3 Programs School Health TM BENEFITS • Sequenced protocols permit a full test battery with the press of only one button. • OAE and tympanometry are completed in as little as 20 seconds. • Easy operation for every level of tester. -

Neural and Receptor Cochlear Potentials Obtained by Transtympanic Electrocochleography in Auditory Neuropathy Q

Clinical Neurophysiology 119 (2008) 1028–1041 www.elsevier.com/locate/clinph Neural and receptor cochlear potentials obtained by transtympanic electrocochleography in auditory neuropathy q Rosamaria Santarelli a,*, Arnold Starr b, Henry J. Michalewski b, Edoardo Arslan a a Department of Medical and Surgical Specialities, Service of Audiology and Phoniatrics, University of Padua, Via Giustiniani 2, I-35128 Padua, Italy b Department of Neurology, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA Accepted 26 January 2008 Abstract Objective: Transtympanic electrocochleography (ECochG) was recorded bilaterally in children and adults with auditory neuropathy (AN) to evaluate receptor and neural generators. Methods: Test stimuli were clicks from 60 to 120 dB p.e. SPL. Measures obtained from eight AN subjects were compared to 16 normally hearing children. Results: Receptor cochlear microphonics (CMs) in AN were of normal or enhanced amplitude. Neural compound action potentials (CAPs) and receptor summating potentials (SPs) were identified in five AN ears. ECochG potentials in those ears without CAPs were of negative polarity and of normal or prolonged duration. We used adaptation to rapid stimulus rates to distinguish whether the gen- erators of the negative potentials were of neural or receptor origin. Adaptation in controls resulted in amplitude reduction of CAP twice that of SP without affecting the duration of ECochG potentials. In seven AN ears without CAP and with prolonged negative potential, adaptation was accompanied by reduction of both amplitude and duration of the negative potential to control values consistent with neural generation. In four ears without CAP and with normal duration potentials, adaptation was without effect consistent with receptor generation. -

Hyperbilirubinemia and Follow-Up Auditory Brainstem Responses in Preterm Infants

Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology Vol. 12, No. 2: 163-168, May 2019 https://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2018.00899 pISSN 1976-8710 eISSN 2005-0720 Original Article Hyperbilirubinemia and Follow-up Auditory Brainstem Responses in Preterm Infants Gi-Sung Nam1 ·Sang Hyun Kwak2·Seong Hoon Bae2·Sung Huhn Kim2·Jinsei Jung2,* ·Jae Young Choi2,* 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, College of Medicine, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju; 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Objectives. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is considered one of the most common causative factors of hearing loss. Preterm infants are more vulnerable to neuronal damage caused by hyperbilirubinemia. This study aimed to evaluate the ef- fect of hyperbilirubinemia on hearing threshold and auditory pathway in preterm infants by serial auditory brain- stem response (ABR). In addition, we evaluate the usefulness of the unconjugated bilirubin (UCB) level compared with total serum bilirubin (TSB) on bilirubin-induced hearing loss. Methods. This study was conducted on 70 preterm infants with hyperbilirubinemia who failed universal newborn hearing screening by automated ABR. The diagnostic ABR was performed within 3 months after birth. Follow-up ABR was conducted in patients with abnormal results (30 cases). TSB and UCB concentration were compared according to hearing threshold by ABR. Results. The initial and maximal measured UCB concentration for the preterm infants of diagnostic ABR ≥40 dB nHL group (n=30) were statistically higher compared with ABR ≤35 dB nHL group (n=40) (P=0.031 and P=0.003, re- spectively). In follow-up ABR examination, 13 of the ABR ≥40 dB nHL group showed complete recovery, but 17 had no change or worsened. -

Audiologic Impairment Associated with Bilirubin-Induced Neurologic Damage

Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 20 (2015) 42e46 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/siny Review Audiologic impairment associated with bilirubin-induced neurologic damage * Cristen Olds, John S. Oghalai Department of Otolaryngology e Head and Neck Surgery, Stanford University, 801 Welch Road, Stanford, CA 94305-5739, USA summary Keywords: Hyperbilirubinemia occurs commonly in neonates and is usually mild and transient, with no long-lasting Bilirubin sequelae. However, bilirubin-induced neurologic damage may occur in some infants. The auditory Kernicterus pathway is the most sensitive part of the central nervous system to bilirubin-induced toxicity, and Auditory neuropathy permanent sequelae may result from only moderately elevated total serum/plasma bilirubin levels. The Hyperbilirubinemia Auditory brainstem response damage to the auditory system occurs primarily within the brainstem and cranial nerve VIII, and manifests clinically as auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction auditory function [15]. This review explores the mechanisms contributing to auditory system damage due to BIND, and describes Hyperbilirubinemia affects up to 84% of term and late preterm its manifestations in the pediatric population. infants in the first week of life [1]. The elevation of total serum/ plasma bilirubin (TB) levels is generally mild, transitory, and, for most children, inconsequential. However, a subset of infants expe- 2. Cellular mechanisms of BIND riences lifelong neurological sequelae. Although the prevalence of classic kernicterus has fallen steadily in the USA in recent years, the Animal studies have shown that unconjugated bilirubin incidence of jaundice in term and premature infants has increased passively diffuses across cell membranes and the blood‒brain [2,3], and kernicterus remains a significant problem in the global barrier (BBB), and bilirubin not removed by organic anion efflux arena [4]. -

Chronic Auditory Toxicity in Late Preterm and Term Infants with Significant Hyperbilirubinemia

Chronic Auditory Toxicity in Late Sanjiv B. Amin, MBBS, MD, MS, a Satish Saluja, MBBS, MD, b Arvind Saili, MBBS, MD, c Mark Orlando, PretermPhD, d Hongyue Wang, PhD, e Nirupamaand Laroia, Term MBBS, MD, a AshaInfants Agarwal, MSf With Significant Hyperbilirubinemia BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: abstract Significant hyperbilirubinemia (SHB) may cause chronic auditory toxicity (auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder and/or sensorineural hearing loss); however, total serum bilirubin (TSB) does not discriminate neonates at risk for auditory toxicity. Our objective was to compare TSB, bilirubin albumin molar ratio (BAMR), and ≥ unbound bilirubin (UB) for their association with chronic auditory toxicity in neonates with METHODS: SHB (TSB 20 mg/dL≥ or TSB’ that met criteria for exchange transfusion). Infants 34 weeks gestational age (GA) with SHB during the first 2 postnatal weeks were eligible for a prospective longitudinal study in India. Comprehensive auditory evaluations were performed at 2 to 3 months of age by using auditory brainstem response, tympanometry, and an otoacoustic emission test and at 9 to 12 months of age by using audiometry. The evaluations were performed by an audiologist unaware of the degree of RESULTS: jaundice. A total of 93 out of 100 infants (mean GA of 37.4 weeks; 55 boys, 38 girls) who were enrolled with SHB were evaluated for auditory toxicity. Of those, 12 infants (13%) had auditory toxicity. On regression analysis controlling for covariates, peak UB (but not – P = peak TSB or peak BAMR), was associated with auditory toxicity (odds ratio 2.41; 95% confidence interval: 1.43 4.07;P .001). There was significant difference in the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves between UB (0.866), TSB (0.775), and BAMR CONCLUSIONS: (0.724) for auditory toxicity ( = .03) after controlling for covariates. -

Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder Gail Padish Clarin, Aud

ANATIONAL RESOURCE CENTER GUIDE FOR FOR EARLY HEARING HEARING ASSESSMENT DETECTION & & MANAGEMENT INTERVENTION Chapter 8 Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder Gail Padish Clarin, AuD uditory Neuropathy Spectrum (8th nerve). They advocate use of the term Use of the term Disorder (ANSD) is a term “neural hearing loss” to describe pathology “neuropathy” to describe Arecently recommended by an in spiral ganglion cells or the central this disorder has resulted expert panel in the audiology profession nervous system and “sensory hearing loss” in much discussion in the to describe hearing loss characterized by to describe loss resulting from pathology normal or near normal cochlear hair cell in the hair cells. audiology profession. function and absent or abnormal auditory nerve function.1 Difficulty hearing in noise, In an effort to be consistent with recent fluctuating hearing, and speech perception terminology used in the audiology performance not predicted by level of profession regarding this type of hearing residual hearing have been reported loss, the term ANSD will be utilized (Starr et al., 1996; Rance et al., 1999). in this chapter. The vast etiologies of The incidence of ANSD in children with ANSD result in a heterogeneous group severe-profound hearing loss has been of patients—each who must be managed reported as 13.4% (Sanyebhaa et al., 2009). methodically and individually for optimal communication and developmental Use of the term progress. An understanding of what is “neuropathy” to describe known about ANSD and what remains this disorder has resulted unknown will assist the pediatric in much discussion in audiologist in appropriate identification the audiology profession. -

A Tutorial on Auditory Neuropathy/ Dyssynchrony for the Speech-Language Pathologist and Audiologist

A Tutorial on Auditory Neuropathy/ Dyssynchrony for the Speech-Language Pathologist and Audiologist Kristin Uhler, Ph.D., CCC-A, FAAA,1 Amanda Heringer, B.A. (Au.D. candidate),2 Nanette Thompson, M.A., CCC-SLP,3 and Christine Yoshinaga-Itano, Ph.D.2 ABSTRACT This article presents information about developmental out- comes of children with auditory neuropathy/auditory dyssynchrony (AN). Colorado data on the number of children screened and the number of children identified with unilateral and bilateral AN will be described. Descriptive information about the percent of children with AN with cognitive disability and disabilities other than hearing loss will be presented. Language outcomes of children with normal cognitive development will be presented. This article will also provide informa- tion about etiologies and audiological information of children with AN. It includes assessment tools that have been useful in decision making for children with AN. KEYWORDS: Auditory neuropathy, auditory dyssynchrony, auditory neural hearing loss, auditory neuropathy spectrum Downloaded by: SASLHA. Copyrighted material. disorder, language development Learning Outcomes: As a result of this activity, the reader will be able to (1) describe the anticipated number of children with auditory neuropathy/auditory dyssynchrony (AN) with cognitive disability and the percentage of children anticipated with any disability other than hearing loss, (2) describe the etiologies associated with AN, (3) describe the considerations for cochlear implant candidacy of children with AN, (4) describe an assessment procedure that can be used in the first year of life to examine the child’s vocal development and the contribution of auditory skill to that development, (5) discuss issues related to choices of communication approaches and AN. -

Redalyc.Auditory Evoked Potentials in a Newborn Wistar Rat Model Of

Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology ISSN: 1808-8694 [email protected] Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico- Facial Brasil Çal, Gökdoan; Genç, Aydan; Gülbahar, Özlem; Gökdoan, Ozan; Helvac, Aye; Üstün Bezgin, Selin; Memi, Leyla Auditory evoked potentials in a newborn Wistar rat model of hyperbilirubinemia Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, vol. 82, núm. 2, marzo-abril, 2016, pp. 144-150 Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial São Paulo, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=392444758005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Document downloaded from http://bjorl.elsevier.es day 04/04/2016. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82(2):144---150 Brazilian Journal of OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY www.bjorl.org ORIGINAL ARTICLE Auditory evoked potentials in a newborn Wistar rat ଝ,ଝଝ model of hyperbilirubinemia a,∗ b c d C¸a˘gıl Gökdo˘gan , Aydan Genc¸ , Özlem Gülbahar , Ozan Gökdo˘gan , e f e Ays¸e Helvacı , Selin Üstün Bezgin , Leyla Memis¸ a Gazi University Hospital, Audiology Department, Ankara, Turkey b Hacettepe University Hospital, Audiology Department, Ankara, Turkey c Gazi University Hospital, Biochemistry Department, Ankara, Turkey d Memorial Hospital, ENT Department, Ankara, Turkey e Gazi University Hospital, Pathology Department, Ankara, Turkey f Gazi University Hospital, ENT Department, Ankara, Turkey Received 7 September 2014; accepted 6 January 2015 Available online 2 December 2015 KEYWORDS Abstract Hyperbilirubinemia; Introduction: Hyperbilirubinemia is a common health problem in newborns. -

Auditory Neuropathies and Electrocochleography

Hearing, Balance and Communication, 2013; 11: 130–137 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Auditory neuropathies and electrocochleography ROSAMARIA SANTARELLI 1 , IGNACIO DEL CASTILLO 2,3 & ARNOLD STARR 4 1 Department of Neuroscience, Service of Audiology and Phoniatrics, University of Padua, Padova, Italy, 2 Unidad de Gen é tica Molecular, Hospital Ram ó n y Cajal and 3 Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red de Enfermedades raras (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain, and 4 University of California, Irvine, California, USA Abstract Auditory neuropathy (AN) is a hearing disorder characterized by disruption of temporal coding of acoustic signals in audi- tory nerve fi bres resulting in impairment of auditory perceptions relying on temporal cues (1,2). Mechanisms suggested include both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic disorders affecting inner hair cell (IHC) depolarization, neurotransmitter release from ribbon synapses, spike initiation in auditory nerve terminals, loss of nerve fi bres and impaired conduction, all occurring in the presence of normal physiological measures of outer hair cell (OHC) activities (otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) and cochlear microphonic (CM)). Disordered synchrony of auditory nerve discharge has been suggested as the basis of both the profound alterations of auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) and impairment of speech perception (3). We review how electrocochleography (ECochG) can provide detailed information to help defi ne objectively the sites of auditory neural dysfunction as affecting IHC receptor summating potential (SP) and compound action