Passed Legislation Unilaterally Annexing East Jerusalem.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arab Israeli Teachers Working in Jewish Schools and Jewish Teachers Working in Arab Israeli Schools Nachum Blass1

Arab Israeli Teachers Working in Jewish Schools and Jewish Teachers Working in Arab Israeli Schools Nachum Blass1 Background In Israel, there is a separation between the Jewish education system and the Arab Israeli education system. The decision for this separation has both practical and ideological explanations. There are those who claim that the demographic realities dictate this separation. However it is revealing that the policy since the founding of the state was to strengthen and preserve the Jewish identity amongst the Jewish sector, and a coming to terms with the national identity of the Arab Israeli pupils. The ideological component is the more important of the two; this is evidenced by the fact that even in places where it would be possible to establish a combined education system, like in mixed cities (Tel Aviv-Yaffo, Haifa, Jerusalem, Acco, Lod, and Ramla), there is a complete separation between the two systems. This separation exists in every part of the education system although it is the most severe in the State-religious and Haredi education. There it is backed by instructions at the highest level that “advise” in no uncertain terms against the hiring of Arab Israeli teachers. This reality has many implications both on the educational level and on the overall societal level. On the educational level, it intensifies the fluctuations in supply and demand for teachers due to the limitations it creates in moving from sector to sector. On the 1 Nachum Blass, senior researcher at the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. Thanks to Haim Bleikh, researcher at the Taub Center, who coordinated the data analysis. -

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

Food Insecurity and Local Responses to Fragmentation of The

European Union FAO EC-FAO Food Securiity IInformatiion for Actiion Programme Strengtheniing Resiilliience: Food IInsecuriity and Locall Responses to Fragmentatiion of the West Bank Apriill 2007 Acknowledgements Special acknowledgement and gratitude is extended to the European Commission under the EC-FAO Food Security Information for Action Program, for facilitating the means to carry out the present study. Additional acknowledgement and thanks are extended to the following: The team: Caroline Abu-Sada, Food Security Analyst, FAO; Amer Madi, Socio-Economist, Al-Sahel Company for Institutional Development and Communication; Ahmad Uweidat, Market Analyst, Al-Sahel Company for Institutional Development and Communication; Nora Lester Murad, editorial consultant, FAO and Sonia Najjar, Communications Officer, FAO. Additional support from: Shawkat Sarsour, General Manager, Al-Sahel; Omar Abu Ghosh, Field Researcher, Al Sahel; Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor, FAO; Rana Hannoun, National Programme Manager, FAO; Salah Lahham, Senior Programme Assistant, VAM Unit, WFP; Fuad Abu Seif, Southern Area Coordinator, UAWC; Riyad Abu Hashem, Project Coordinator, UAWC; Mustafa Tamaizh, Food Security Project Officer, Oxfam GB; Hisham Sawafta, Food Security Programme Manager, CARE International; Dr. Jamil Ahmad, Food Security Programme Manager, ACH; Christophe Driesse, Economic Security Coordinator, ICRC; Workshop participants from: the Ministry of Agriculture; UNDP; PARC; UAWC; Maisem Agricultural Export Company; World Vision; and, the Palestinian Olive Oil Council. It is noteworthy that the study would not have been possible without the participation of the families, wholesalers, retailers, charitable societies, and Zakat committees who agreed to be interviewed and share their experiences. We thank them for shedding light on their daily realities as related to fragmentation, food insecurity as well as their coping mechanisms. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

KIRYAT ANAVIM, 1921 LESSON OVERVIEW Kiryat Anavim (City of Vineyards) Is a Kibbutz in the Judean Hills Near Jerusalem

ANALYZING PRIMARY SOURCES CASE LEARNING ACTIVITY KIRYAT ANAVIM, 1921 LESSON OVERVIEW Kiryat Anavim (City of Vineyards) is a Kibbutz in the Judean Hills near Jerusalem. The land that would become the Kibbutz was bought in 1913-14 by the Palestine Land Development Company Organization from ‘Abdallah Effendi Abu Ghosh and ‘Abd al-Hamid Effendi Abu as part of the purchase of Dilb which had begun in 1910. The first settlers were a group of Jewish workers from Bialystock who, due to onset of World War I, vacated the area. The Kibbutz was founded in 1920 by a group of agricultural settlers from Eastern Europe who came as part of the Third Aliyah (see timeline 1919-1923). At first settlement and cultivation was difficult, especially as the settlers lacked sufficient financial resources, to develop modern farming on the hilly terrain. In 1920, the Jewish National Fund provided some financial assistance that helped the settlers by building terraces, planting saplings and. By the end of 1920 there were around 200 pioneers in Kiryat Anavim. In this lesson, students will analyze two photographs from Kiryat Anavim taken in 1921 and use their observations to produce a news story. ENDURING UNDERSTANDING Immigrants to Israel in 1920 faced many difficulties and worked hard to build and develop the infrastructure for the Jewish State. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS What was life like for pioneers to Israel in the 1920’s? What type of work did the pioneers need to do in order to develop the land? OBJECTIVES: Students will: Analyze two historical photographs Construct meaning from their observations Learn about how chroma key (green screen) photography and video work. -

1 2017 Annual Report 2017 Had the Dubious Distinction Of

. 2017 Annual Report 2017 had the dubious distinction of marking the 50th anniversary of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. After half a century, during which Israel’s policies have created profound changes that indicate long-term intentions, it is clear that this reality cannot be viewed as temporary. In 2017, B'Tselem continued to document and publicize human rights violations, while exposing the injustice, violence and dispossession at the very core of the occupation regime, challenging its legitimacy in Israel and abroad, and helping to expedite its end. 1 Table of Contents 2017 in Numbers 3 Executive Director's Note 5 Marking the 50th year of the Occupation 6 Photography Exhibit 6 Media Surrounding the 50th Anniversary 8 Reports Published in 2017 8 Getting Off Scot-Free 8 Made in Israel: Exploiting Palestinian Land for Treatment of Israeli Waste 9 Unprotected: Detention of Palestinian Teenagers in East Jerusalem 9 Fatalities 10 Trigger-Happy Responses to Clashes, Stone-throwing Incidents, Demonstrations or Evading Arrest 10 A Shoot-to-Kill Approach in Cases Defined as Assault 10 Security Forces Violence Against Palestinians 11 The Gaza Strip – A Decade of Siege 11 Separating Families 12 Gaza Executions 12 Prisoners and Detainees 13 Hunger Strike 13 Minor detainees 13 Communities Facing Demolitions and Displacement in Area C 14 Communities Under Imminent Threat of Transfer 14 An Increasingly Coercive Environment 15 Demolition Data 15 Demolitions in East Jerusalem 16 Batan al-Hawa - -

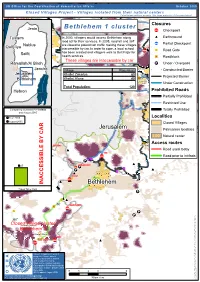

Bethlehem 1 Cluster

º¹DP UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Qalandiya Camp Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated fromÇ theirQalandiya natural centers º¹ ¬Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) village cluster Beit Duqqu P 144 Atarot ### ¬Ç usalem 3 170 Al Judeira Al Jib Closures ## Bir Nabala Beit 'Anan Jenin BethlehemAl Jib 1 cluster Ç Beit Ijza Closed village cluster ¬ Checkpoint ## ## AL Ram CP ## m al Lahim In 2000, villagers would access Bethlehem Ç#along# Earthmound Tulkarm Jerusalem 2 #¬# Al Qubeiba road 60 for their services. In 2005, road 60 and 367 Ç Qatanna Biddu 150 ¬ Partial Checkpoint Nablus 151 are closed to palestinian traffic making these villages Qalqiliya /" # Hizmah CP D inaccessible by car.ramot In ordercp Beit# Hanina to cope,# al#### Balad a local school Ç # ### ¬Ç D Road Gate Salfit has been created¬ and villagers walk to Beit Fajar for Beit Surik health services. /" Roadblock These villages are inaccessible by car Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Surik º¹P Under / Overpass 152## Ç##Shu'fat Camp 'Anata Jericho Village Population¬ Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Khallet Zakariya 80 173 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Khallet Afana 40 /" Al 'Isawiya /" Under Construction Total Population: 120 Az Za'ayyemProhibited Roads Hebron ## º¹AzP Za'ayyem Zayem CP ¬Ç 174 Partially Prohibited Restricted Use Al 'Eizariya Comparing situations Pre-Intifada /" Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Closed village cluster Year 2000 Localities Abu Dis Jerusalem 1 August 2005 Closed Villages 'Arab al Jahalin -

Download This Report

A LICENSE TO KILL Israeli Operations against "Wanted" and Masked Palestinians A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York !!! Washington !!! Los Angeles !!! London Copyright 8 July 1993 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 93-79007 ISBN: 1-56432-109-6 Middle East Watch Middle East Watch was founded in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry and Aziz Abu Hamad are associate directors; Suzanne Howard is the associate. HUMAHUMAHUMANHUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some sixty countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process of law and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of Helsinki Watch by a group of publishers, lawyers and other activists and now maintains offices in New York, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, London, Moscow, Belgrade, Zagreb and Hong Kong. -

Palestinian Nonviolent Resistance to Occupation Since 1967

FACES OF HOPE A Campaign Supporting Nonviolent Resistance and Refusal in Israel and Palestine AFSC Middle East Resource series Middle East Task Force | Fall 2005 Palestinian Nonviolent Resistance to Occupation Since 1967 alestinian nonviolent resistance to policies of occupa- tion and injustice dates back to the Ottoman (1600s- P1917) and British Mandate (1917-1948) periods. While the story of armed Palestinian resistance is known, the equally important history of nonviolent resistance is largely untold. Perhaps the best-known example of nonviolent resistance during the mandate period, when the British exercised colo- nial control over historic Palestine, is the General Strike of 1936. Called to protest against British colonial policies and the exclusion of local peoples from the governing process, the strike lasted six months, making it the longest general strike in modern history. Maintaining the strike for so many months required great cooperation and planning at the local Residents of Abu Ghosh, a village west of Jerusalem, taking the oath level. It also involved the setting up of alternative institu- of allegiance to the Arab Higher Committee, April 1936. Photo: Before tions by Palestinians to provide for economic and municipal Their Diaspora, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1984. Available at http://www. passia.org/. needs. The strike, and the actions surrounding it, ultimately encountered the dilemma that has subsequently been faced again and to invent new strategies of resistance. by many Palestinian nonviolent resistance movements: it was brutally suppressed by the British authorities, and many of The 1967 War the leaders of the strike were ultimately killed, imprisoned, During the 1967 War, Israel occupied the West Bank, or exiled. -

Development Assistance and the Occupied Palestinian Territories

House of Commons International Development Committee Development Assistance and the Occupied Palestinian Territories Fourth Report of Session 2006-07 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 January 2007 HC 114-II Published on 31 January 2007 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 International Development Committee The International Development Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for International Development and its associated public bodies. Current membership Malcolm Bruce MP (Liberal Democrat, Gordon) (Chairman) John Barrett MP (Liberal Democrat, Edinburgh West) John Battle MP (Labour, Leeds West) Hugh Bayley MP (Labour, City of York) John Bercow MP (Conservative, Buckingham) Richard Burden MP (Labour, Birmingham Northfield) Mr Quentin Davies MP (Conservative, Grantham and Stamford) James Duddridge MP (Conservative, Rochford and Southend East) Ann McKechin MP (Labour, Glasgow North) Joan Ruddock MP (Labour, Lewisham Deptford) Mr Marsha Singh MP (Labour, Bradford West) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/indcom Committee staff The staff of the Committee are Carol Oxborough (Clerk), Matthew Hedges (Second Clerk), Anna Dickson (Committee Specialist), Chlöe Challender (Committee Specialist), Alex Paterson (Media Officer), Katie Phelan (Committee Assistant) and Jennifer Steele (Secretary). -

Al-Bireh Ramallah Salfit

Biddya Haris Kifl Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Az Zawiya (Salfit) Talfit Salfit As Sawiya Qusra Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Deir Ballut Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Turmus'ayya Al Lubban al Gharbi 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Bani Zeid Deir as Sudan Sinjil Rantis Jilijliya 'Ajjul An Nabi Salih (Bani Zeid al Gharbi) Al Mughayyir (Ramallah) 'Abud Khirbet Abu Falah Umm Safa Deir Nidham Al Mazra'a ash Sharqiya 'Atara Deir Abu Mash'al Jibiya Kafr Malik 'Ein Samiya Shuqba Kobar Burham Silwad Qibya Beitillu Shabtin Yabrud Jammala Ein Siniya Bir Zeit Budrus Deir 'Ammar Silwad Camp Deir Jarir Abu Shukheidim Jifna Dura al Qar' Abu Qash At Tayba (Ramallah) Deir Qaddis Al Mazra'a al Qibliya Al Jalazun Camp 'Ein Yabrud Ni'lin Kharbatha Bani HarithRas Karkar Surda Al Janiya Al Midya Rammun Bil'in Kafr Ni'ma 'Ein Qiniya Beitin Badiw al Mus'arrajat Deir Ibzi' Deir Dibwan 'Ein 'Arik Saffa Ramallah Beit 'Ur at Tahta Khirbet Kafr Sheiyan Al-Bireh Burqa (Ramallah) Beituniya Al Am'ari Camp Beit Sira Kharbatha al Misbah Beit 'Ur al Fauqa Kafr 'Aqab Mikhmas Beit Liqya At Tira Rafat (Jerusalem) Qalandiya Camp Qalandiya Beit Duqqu Al Judeira Jaba' (Jerusalem) Al Jib Jaba' (Tajammu' Badawi) Beit 'Anan Bir Nabala Beit Ijza Ar Ram & Dahiyat al Bareed Deir al Qilt Kharayib Umm al Lahim QatannaAl Qubeiba Biddu An Nabi Samwil Beit Hanina Hizma Beit Hanina al Balad Beit Surik Beit Iksa Shu'fat 'Anata Shu'fat Camp Al Khan al Ahmar (Tajammu' Badawi) Al 'Isawiya. -

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind.