An Evaluation of Black Bear Management Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINNESOTA MUSTELIDS Young

By Blane Klemek MINNESOTA MUSTELIDS Young Naturalists the Slinky,Stinky Weasel family ave you ever heard anyone call somebody a weasel? If you have, then you might think Hthat being called a weasel is bad. But weasels are good hunters, and they are cunning, curious, strong, and fierce. Weasels and their relatives are mammals. They belong to the order Carnivora (meat eaters) and the family Mustelidae, also known as the weasel family or mustelids. Mustela means weasel in Latin. With 65 species, mustelids are the largest family of carnivores in the world. Eight mustelid species currently make their homes in Minnesota: short-tailed weasel, long-tailed weasel, least weasel, mink, American marten, OTTERS BY DANIEL J. COX fisher, river otter, and American badger. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer May–June 2003 n e MARY CLAY, DEMBINSKY t PHOTO ASSOCIATES r mammals a WEASELS flexible m Here are two TOM AND PAT LEESON specialized mustelid feet. b One is for climb- ou can recognize a ing and the other for hort-tailed weasels (Mustela erminea), long- The long-tailed weasel d most mustelids g digging. Can you tell tailed weasels (M. frenata), and least weasels eats the most varied e food of all weasels. It by their tubelike r which is which? (M. nivalis) live throughout Minnesota. In also lives in the widest Ybodies and their short Stheir northern range, including Minnesota, weasels variety of habitats and legs. Some, such as badgers, hunting. Otters and minks turn white in winter. In autumn, white hairs begin climates across North are heavy and chunky. Some, are excellent swimmers that hunt to replace their brown summer coat. -

Food Habits of Black Bears in Suburban Versus Rural Alabama

Food Habits of Black Bears in Suburban versus Rural Alabama Laura Garland, Auburn University, School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences, Auburn, AL 36849 Connor Ellis, 18832 #1 Gulf Boulevard Indian Shores, FL 33785 Todd Steury, Auburn University, School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences, Auburn, AL 36849 Abstract: Little is known about the food habits of black bears (Ursus americanus) in Alabama. A major concern is the amount of human influence in the diet of these bears as human and bear populations continue to expand in a finite landscape and bear-human interactions are increasing. To better understand dietary habits of bears, 135 scats were collected during late August to late November 2011–2014. Food items were classified into the cat- egories of fruit, nuts/seeds, insects, anthropogenic, animal hairs, fawn bones, and other. Plant items were classified down to the lowest possible taxon via visual and DNA analysis as this category composed the majority of scat volumes. Frequency of occurrence was calculated for each food item. The most commonly occurring foods included: Nyssa spp. (black gum, 25.2%), Poaceae family (grass, 24.5%), Quercus spp. (acorn, 22.4%), and Vitis spp. (muscadine grape, 8.4%). Despite the proximity of these bear populations to suburban locations, during our sampling period we found that their diet primarily comprised vegetation, not anthropogenic food; while 100% of scat samples contained vegetation, only 19.6% of scat samples contained corn and no other anthropogenic food sources were detected. Based on a Fisher’s exact test, dietary composition did not differ between bears living in subur- ban areas compared to bears occupying more rural areas (P = 0.3891). -

2020-2021 Arizona Hunting Regulations

Arizona Game and Fish Department 2020-2021 Arizona Hunting Regulations This publication includes the annual regulations for statewide hunting of deer, fall turkey, fall javelina, bighorn sheep, fall bison, fall bear, mountain lion, small game and other huntable wildlife. The hunt permit application deadline is Tuesday, June 9, 2020, at 11:59 p.m. Arizona time. Purchase Arizona hunting licenses and apply for the draw online at azgfd.gov. Report wildlife violations, call: 800-352-0700 Two other annual hunt draw booklets are published for the spring big game hunts and elk and pronghorn hunts. i Unforgettable Adventures. Feel-Good Savings. Heed the call of adventure with great insurance coverage. 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on motorcycle insurance. geico.com | 1-800-442-9253 | Local Office Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2019 GEICO ii ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT — AZGFD.GOV AdPages2019.indd 4 4/20/2020 11:49:25 AM AdPages2019.indd 5 2020-2021 ARIZONA HUNTING4/20/2020 REGULATIONS 11:50:24 AM 1 Arizona Game and Fish Department Key Contacts MAIN NUMBER: 602-942-3000 Choose 1 for known extension or name Choose 2 for draw, bonus points, and hunting and fishing license information Choose 3 for watercraft Choose 4 for regional -

Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia Without Proper Restraint Device

J Vet Clin 26(1) : 113-116 (2009) Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled Out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia without Proper Restraint Device Hwan-Yul Yong1, Suk-Hyun Park, Myoung-Keun Choi, So-Young Jung, Dae-Chang Ku, Jong-Tae Yoo, Mi-Jin Yoo, Mi-Hyun Yoo, Kyung-Yeon Eo, Yong-Gu Yeo, Shin-Keun Kang and Heon-Youl Kim Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon 427-080, Korea (Accepted : January 28, 2009 ) Abstract : A 4-year-old female reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata), at Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon, Korea had a male calf with no help of proper restraint devices. The mother giraffe was in a danger of dystocia more than 7 hours in labor after showing the calf’s toe of the foreleg which protruded from her vulva. After tugging with a snare of rope on the metacarpal bone of the calf and pulling it, the other toe emerged. Finally, with two snares around each of metacarpal bones, the calf was completely pulled out by zoo staff. After parturition, the dam was in normal condition for taking care of the calf and her progesterone hormone had also dropped down to a normal pre-pregnancy. Key words : giraffe, dystocia, rope, parturition. Introduction giraffe. Because a giraffe is generally known as having such an uneventful gestation and not clearly showing appearances Approaching the megavertebrate species such as ele- of body with which zoo keepers notice impending parturi- phants, rhinoceroses and giraffes without anesthetic agents or tion until just several weeks before parturition. A few of zoo proper physical restraint devices is very hard, and it is even keepers were not suspicious of her being pregnant when they more difficult when it is necessary to stay near to the ani- saw the extension of the giraffe’s abdomen around 2 weeks mals for a long period (1,2,5). -

FISHER Pekania Pennanti

WILDLIFE IN CONNECTICUT WILDLIFE FACT SHEET FISHER Pekania pennanti Background J. FUSCO © PAUL In the nineteenth century, fishers became scarce due to forest logging, clearing for agriculture, and overexploitation. By the 1900s, fishers were considered extirpated from the state. Reforestation and changes in land-use practices have restored the suitability of the fisher’s habitat in part of its historic range, allowing a population to recolonize the northeastern section of the state. Fishers did not recolonize suitable habitat in northwestern Connecticut, since the region was isolated from a source population. Fishers were rare in western Massachusetts, and the developed and agricultural habitats of the Connecticut River Valley were a barrier to westward expansion by fishers in northeastern Connecticut. A project to reintroduce this native mammal into northwestern Connecticut was initiated by the Wildlife Division in 1988. Funds from reimbursement of trapping wild turkeys in Connecticut for release in Maine were used to purchase fishers caught by cooperating trappers in New Hampshire and Vermont. In what is termed a "soft release," fishers were penned and fed at the release site for a couple of weeks prior to being released. Through radio and snow tracking, biologists later found that the fishers that were released in northwestern Connecticut had high survival rates and successfully reproduced. As a result of this project, a viable, self-sustaining population of this native mammal is now established in western Connecticut. Fishers found throughout eastern Connecticut are a result of natural range expansion. In 2005, Connecticut instituted its first modern day regulated trapping season for fishers. Most northern states have regulated fisher trapping seasons. -

Deer, Elk, Bear, Moose, Lynx, Bobcat, Waterfowl

Hunt ID: 1501-CA-AL-G-L-MDeerWDeerElkBBearMooseLynxBobcatWaterfowl-M1SR-O1G-N2EGE Great Economy Deer and Moose Hunts south of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada American Hunters trekking to Canada for low cost moose, along with big Mule Deer and Whitetail and been pleasantly surprised by the weather and temperatures that they were greeted by when they hunted British Columbia, located in Canada, north of Washington State. Canada should be and is cold but there are exceptions, if you know where to go. In BC if you stay on the western Side of the Rocky Mountains the weather is quite mild because it is warmed by the Pacific Ocean. If you hunt east of the Rocky Mountains, what I call the Canadian Interior it can be as much as 50 degrees colder depending on the time of the year. The area has now preference point requirements, the Outfitter has his allotted vouchers so you can get a reasonably priced license and, in most cases, less than you can get for the same animal in the US as a non-resident. You don’t even buy the voucher from the Outfitter it is part of his hunt cost because without it you could not get a license anyway. Travel is easy and the residents are friendly. Like anywhere outside the US you will need a easy to acquire Passport if you don’t have one, just don’t wait until the last minute to get one for $10 from your local Post office by where you live. The one thing in Canada is if you have a felony on your record Canada will not allow you into their safe Country. -

2021 Fur Harvester Digest 3 SEASON DATES and BAG LIMITS

2021 Michigan Fur Harvester Digest RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or Text (800) 292-7800 Michigan.gov/Trapping Table of Contents Furbearer Management ...................................................................3 Season Dates and Bag Limits ..........................................................4 License Types and Fees ....................................................................6 License Types and Fees by Age .......................................................6 Purchasing a License .......................................................................6 Apprentice & Youth Hunting .............................................................9 Fur Harvester License .....................................................................10 Kill Tags, Registration, and Incidental Catch .................................11 When and Where to Hunt/Trap ...................................................... 14 Hunting Hours and Zone Boundaries .............................................14 Hunting and Trapping on Public Land ............................................18 Safety Zones, Right-of-Ways, Waterways .......................................20 Hunting and Trapping on Private Land ...........................................20 Equipment and Fur Harvester Rules ............................................. 21 Use of Bait When Hunting and Trapping ........................................21 Hunting with Dogs ...........................................................................21 Equipment Regulations ...................................................................22 -

Hunting Deer in California

HUNTING DEER IN CALIFORNIA We hope this guide will help deer hunters by encouraging a greater understanding of the various subspecies of mule deer found in California and explaining effective hunting techniques for various situations and conditions encountered throughout the state during general and special deer seasons. Second Edition August 2002 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Arnold Schwarzenegger, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME L. Ryan Broddrick, Director WILDLIFE PROGRAMS BRANCH David S. Zezulak, Ph.D., Chief Written by John Higley Technical Advisors: Don Koch; Eric Loft, Ph.D.; Terry M. Mansfield; Kenneth Mayer; Sonke Mastrup; Russell C. Mohr; David O. Smith; Thomas B. Stone Graphic Design and Layout: Lorna Bernard and Dana Lis Cover Photo: Steve Guill Funded by the Deer Herd Management Plan Implementation Program TABLE OF CON T EN T S INTRODUCT I ON ................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: THE DEER OF CAL I FORN I A .........................................................................................................7 Columbian black-tailed deer ....................................................................................................................8 California mule deer ................................................................................................................................8 Rocky Mountain mule deer .....................................................................................................................9 -

Public Attitudes Toward and Awareness of Trapping Issues In

ATTITUDES TOWARD AND AWARENESS OF TRAPPING ISSUES IN CONNECTICUT, INDIANA AND WISCONSIN Conducted for the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies And the Furbearer Resources Technical Work Group Conducted by Responsive Management May 2001 ATTITUDES TOWARD AND AWARENESS OF TRAPPING ISSUES IN CONNECTICUT, INDIANA AND WISCONSIN May 2001 CONDUCTED BY RESPONSIVE MANAGEMENT NATIONAL OFFICE Mark Damian Duda, Executive Director Peter E. De Michele, Ph.D., Director of Research Steven J. Bissell, Ph.D., Qualitative Research Director Ping Wang, Ph.D., Quantitative Research Associate Jim Herrick, Ph. D., Research Associate Alison Lanier, Business Manager William Testerman, Survey Center Manager Joy Yoder, Research Associate 130 Franklin Street, PO Box 389 Harrisonburg, VA 22801 Phone: 540/432-1888 Fax: 540/432-1892 E-mail to: [email protected] www.responsivemanagement.com EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW Executive Overview of Findings, Implications and Conclusions The purpose of this project was to assist the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (IAFWA) and the Furbearer Resources Technical Work Group in better understanding public awareness of, opinions on, and attitudes toward trapping. There were five phases to this project. Phase I was a series of focus groups with members of the general population in Connecticut, Wisconsin, and Indiana (Chapter 1). Phase II consisted of focus groups with two important stakeholder groups: Wildlife professionals (Chapter III), and Veterinarians (Chapter 1). Phase III consisted of utilizing the focus group results to develop a comprehensive group of questions regarding the most salient issues related to public opinion on, and attitudes toward trapping. These survey questions formed the basis of the development of three separate survey instruments that can be used by wildlife agencies to periodically assess attitudes toward trapping on a local, state or national level (Chapter IV). -

Brown Bear (Ursus Arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende Images by John Schoen

Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende images by John Schoen Two hundred years ago, brown (also known as grizzly) bears were abundant and widely distributed across western North America from the Mississippi River to the Pacific and from northern Mexico to the Arctic (Trevino and Jonkel 1986). Following settlement of the west, brown bear populations south of Canada declined significantly and now occupy only a fraction of their original range, where the brown bear has been listed as threatened since 1975 (Servheen 1989, 1990). Today, Alaska remains the last stronghold in North America for this adaptable, large omnivore (Miller and Schoen 1999) (Fig 1). Brown bears are indigenous to Southeastern Alaska (Southeast), and on the northern islands they occur in some of the highest-density FIG 1. Brown bears occur throughout much of southern populations on earth (Schoen and Beier 1990, Miller et coastal Alaska where they are closely associated with salmon spawning streams. Although brown bears and grizzly bears al. 1997). are the same species, northern and interior populations are The brown bear in Southeast is highly valued by commonly called grizzlies while southern coastal populations big game hunters, bear viewers, and general wildlife are referred to as brown bears. Because of the availability of abundant, high-quality food (e.g. salmon), brown bears enthusiasts. Hiking up a fish stream on the northern are generally much larger, occur at high densities, and have islands of Admiralty, Baranof, or Chichagof during late smaller home ranges than grizzly bears. summer reveals a network of deeply rutted bear trails winding through tunnels of devil’s club (Oplopanx (Klein 1965, MacDonald and Cook 1999) (Fig 2). -

Effect of Pheromone Trap Density on Mass Trapping Of

SCIENTIFIC NOTE 281 EFFECT OF PHEROMONE TRAP DENSITY ON MASS TRAPPING OF MALE POTATO TUBER MOTH Phthorimaea operculella (ZELLER) (LEPIDOPTERA: GELECHIIDAE), AND LEVEL OF DAMAGE ON POTATO TUBERS Patricia Larraín S.1*, Michel Guillon2, Julio Kalazich3, Fernando Graña1, and Claudia Vásquez1 ABSTRACT Potato tuber moth (PTM), Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller), is one of the pests that cause the most damage to potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) in both field crops and storage, especially in regions where summers are hot and dry. Larvae develop in the foliage and tubers of potatoes and cause direct losses of edible product. The use of synthetic pheromones that interfere with insect mating for pest control has been widely demonstrated in numerous Lepidoptera and other insect species. An experiment was carried out during the 2004-2005 season in Valle del Elqui, Coquimbo Region, Chile, to evaluate the effectiveness of different pheromone trap densities to capture P. operculella males for future development of a mass trapping technique, and a subsequent decrease in insect reproduction. The study evaluated densities of 10, 20, and 40 traps ha-1, baited with 0.2 mg of PTM sexual pheromone, and water- detergent for captures. Results indicated that larger numbers of male PTM were captured per trap with densities of 20 and 40 traps per hectare, resulting in a significant reduction (P < 0.05) of tuber damage in these treatments compared with the control which used conventional chemical insecticide sprays. Key words: potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella, mass trapping, pheromone. INTRODUCTION researched (El-Sayed et al., 2006). It interferes with insect mating, reducing the future larvae population and The potato tuber moth is a pest which economically subsequent damage. -

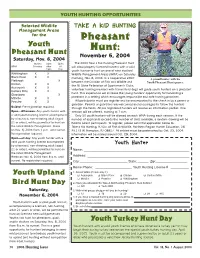

Pheasant Hunt

YOUTH HUNTING OPPORTUNITIES Selected Wildlife TAKE A KID HUNTING Management Areas for the Pheasant Youth Pheasant Hunt Hunt: November 6, 2004 Saturday, Nov. 6, 2004 Guided Open Open The 2004 Take a Kid Hunting Pheasant Hunt WMA Morning After All will allow properly licensed hunters with a valid 1 pm Day youth license to hunt on one of nine stocked Whittingham X X Wildlife Management Areas (WMA) on Saturday Black River X X morning, Nov. 6, 2004. In a cooperative effort A proud hunter with his Flatbrook X between the Division of Fish and Wildlife and Youth Pheasant Hunt quarry. Clinton X X the NJ State Federation of Sportsmen’s Clubs, Assunpink X X volunteer hunting mentors with trained bird dogs will guide youth hunters on a pheasant Colliers Mills X X hunt. This experience will increase the young hunters’ opportunity for harvesting a Glassboro X Millville X X pheasant in a setting which encourages responsible and safe hunting practices. Peaslee X X All participants must pre-register and be accompanied to the check-in by a parent or guardian. Parents or guardians are welcomed and encouraged to follow the hunters Guided: Pre-registration required. through the fields. All pre-registered hunters will receive an information packet. One Open—Afternoon: Any youth hunter with session will be offered, starting at 7 a.m. a valid youth hunting license accompanied Only 50 youth hunters will be allowed on each WMA during each session. If the by a licensed, non-shooting adult (aged number of applicants exceeds the number of slots available, a random drawing will be 21 or older), will be permitted to hunt on held to select participants.