The Flagler Review the Flagler RE FLA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/11/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/11/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Someone Like You - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Piano Man - Billy Joel At Last - Etta James Don't Stop Believing - Journey Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Wannabe - Spice Girls Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Jackson - Johnny Cash Free Fallin' - Tom Petty Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Look What You Made Me Do - Taylor Swift I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Santeria - Sublime Summer Nights - Grease Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Turn The Page - Bob Seger Zombie - The Cranberries Crazy - Patsy Cline Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Kryptonite - 3 Doors Down My Girl - The Temptations Despacito (Remix) - Luis Fonsi Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Monster Mash - Bobby Boris Pickett Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's My Way - Frank Sinatra In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Rolling In The Deep - Adele All Of Me - John Legend These -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

SBS Eurovision Songbook

ALBANIA Semi Final 2 / Saturday 14 May 7:30pm SBS Australia Artist: Eneda Tarifa Song: Fairytale This tale of love, larger than dreams, it may take a lifetime, To understand what it means. Many the tears, cos all the craziness and rage, Tale of love, the massage is Love can bring change. Cos it’s you...only you you I feel, And I ...oh I I know in my soul this it’s real REF And that’s why I love you..oh I Yes I love you u..u.. And I’d fight for you give my life for you my heart But comes a day when it’s not enough and what you have the time is up but it’s hard to turn a new page In the tale, sweet tale of love you will find the peace of heart that you crave Share your party pics #SBSEurovision sbs.com.au/eurovision ARMENIA Semi Final 1 / Friday 13 May 7:30pm SBS Australia Artist: Iveta Mukuchyan Song: LoveWave Hey it’s me. It’s taking over me. Look, I know it might sound strange but suddenly Instrumental I’m not the same I used to be. It’s taking, it’s taking over me. It’s like I’ve stepped out of space and time and come alive… Guess this is what it’s all about Chorus cause… You (oh like a lovewave) Shook my life like an earthquake now 1. ...when it touched me the world went silent, I’m waking up, Calm before the storm reaches me. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 17/12/2016 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 17/12/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs (H?D) Planet Earth My One And Only Hawaiian Hula Eyes Blackout I Love My Baby (My Baby Loves Me) On The Beach At Waikiki Other Side I'll Build A Stairway To Paradise Deep In The Heart Of Texas 10 Years My Blue Heaven What Are You Doing New Year's Eve Through The Iris What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Long Ago And Far Away 10,000 Maniacs When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Bésame mucho (English Vocal) Because The Night 'S Wonderful For Me And My Gal 10CC 1930s Standards 'Til Then Dreadlock Holiday Let's Call The Whole Thing Off Daddy's Little Girl I'm Not In Love Heartaches The Old Lamplighter The Things We Do For Love Cheek To Cheek Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Rubber Bullets Love Is Sweeping The Country That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Life Is A Minestrone My Romance That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) 112 It's Time To Say Aloha I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Cupid We Gather Together Aren't You Glad You're You Peaches And Cream Kumbaya (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 12 Gauge The Last Time I Saw Paris My One And Only Highland Fling Dunkie Butt All The Things You Are No Love No Nothin' 12 Stones Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Personality Far Away Begin The Beguine Sunday, Monday Or Always Crash I Love A Parade This Heart Of Mine 1800s Standards I Love A Parade (short version) Mister Meadowlark Home Sweet Home I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter 1950s Standards Home On The Range Body And Soul Get Me To The Church On -

El Festival De Eurovisión, Desde Su Creación En 1956, Ha Potenciado

El Festival de Eurovisión, desde su creación en 1956, ha potenciado una ficción de comunidad a través del medio audiovisual que aquí se analizará a través de cuatro conceptos: hospitalidad, contención, pronunciación y serialidad. La creciente y exitosa participación de los países “del este” de Europa en el concurso ha favorecido una “venganza de los márgenes” (Björnberg 2007), “representándose” así cierta “condición de periferia” a través de la fórmula “Canción”, limitada a tres minutos, a la temática “no política” de su letra y su despliegue escenográfico. Además, junto a la cuestión idiomática del (dis)continuo flujo de traducción/pronunciación de la gala, dicha participación genera, como espectáculo anual, una programación, siendo el Festival testigo de las transformaciones de la “Europa” de los últimos 60 años. Apoyándonos en tesis existentes el ámbito anglosajón, apostamos así por una relectura del show televisivo no deportivo más multitudinario del mundo desde el análisis y la estética de la imagen en movimiento. Eurovisión, identidad, hospitalidad, espectáculo, serialidad Since his creation (1956), the Eurovision Song Contest has promoted a fiction of community through audio-visual media that here we’ll analyse through concepts of hospitality, containment, pronunciation and seriality. At first, the rising interest and victories from Eastern European countries of this show, allows a sort of “revenge of margins”, an own representation centring notions of periphery. Under the “Sing” formula, limited on three minutes, also in the “non-political” lyrics, and into a scenography display, it have been generated an own entity with the idiomatic question because of the discontinuous flux of translation and pronunciation. -

2016 EUROVISION SWEEPSTAKE Semi-Finals 10 & 12 May | Grand Final 14 May

2016 EUROVISION SWEEPSTAKE Semi-Finals 10 & 12 May | Grand Final 14 May ALBANIA CZECH REPUBLIC IRELAND SAN MARINO Fairytale I Stand Sunlight I Didn’t Know Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by ARMENIA DENMARK ISRAEL SERBIA LoveWave Soldiers Of Love Made Of Stars Goodbye (Shelter) Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by AUSTRALIA ESTONIA ITALY SLOVENIA Sound Of Silence Play No Degree Of Separation Blue And Red Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by AUSTRIA F.Y.R. MACEDONIA LATVIA SPAIN Loin d’ici Dona Heartbeat Say Yay! Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by AZERBAIJAN FINLAND LITHUANIA SWEDEN Miracle Sing It Away I’ve Been Waiting for This Night If I Were Sorry Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by BELARUS FRANCE MALTA SWITZERLAND Help You Fly J’ai cherché Walk On Water The Last Of Our Kind Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by BELGIUM GEORGIA MOLDOVA THE NETHERLANDS What’s The Pressure Midnight Gold Falling Stars Slow Down Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA GERMANY MONTENEGRO UKRAINE Ljubav Je Ghost The Real Thing 1944 Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by BULGARIA GREECE NORWAY UNITED KINGDOM If Love Was A Crime Utopian Land Icebreaker You’re Not Alone Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by CROATIA HUNGARY POLAND Lighthouse Pioneer Color Of Your Life Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by CYPRUS ICELAND RUSSIA Alter Ego Hear Them Calling You Are The Only One Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by 2016 EUROVISION SWEEPSTAKE ALBANIA ARMENIA AUSTRALIA AUSTRIA AZERBAIJAN BOSNIA & BELARUS BELGIUM HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA CROATIA CZECH F.Y.R. -

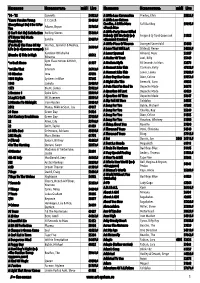

Название Исполнитель Midi Live Название Исполнитель Midi Live

Название Исполнитель midi Live Название Исполнитель midi Live '74 - '75 Connells 54922♫ A Little Less Coversation Presley, Elvis 58822♫ 'Cause You Are Young C.C.Catch 53656♫ A Little Less Sixteen (Everything I Do) I Do It For Candles, A Little More Fall Out Boy 59195♫ Adams, Bryan 53765♫ You «Touch Me» (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 55460♫ A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) (к-ф Fergie & Q-Tip & Goonrock 51958 (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra 59607♫ «Великий Гэтсби») Magdalena (I've Had) The Time Of My Warnes, Jennifer & Medley, A Little Piece Of Heaven Avenged Sevenfold 53880 56930♫ Life (к-ф «Грязные танцы») Bill A Love That Will Last Olstead, Renee 54284♫ Kardinal Offishall & A Lover Spurned Almond, Marc 52387 (Numba 1) Tide Is High 60512 Rihanna A Matter Of Trust Joel, Billy 55449 Gym Class Heroes & Hitch, *ss Back Home 61937 A Modern Myth 30 Seconds to Mars 52876 Neon A Moment Like This Clarkson, Kelly 47158♫ *ss Like That Eminem 56713♫ 10 Minutes Inna 47693 A Moment Like This Lewis, Leona 59382♫ A New Day Has Come Dion, Celine 59753♫ 1001 Nights Systems in Blue 57245 A Night Like This Emerald, Caro 49632 1944 Jamala 59489♫ A Pain That I'm Used To Depeche Mode 56175 1973 Blunt, James 59922♫ A Question Of Lust Depeche Mode 63023 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 58999♫ A Question Of Time Depeche Mode 58647 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 58991♫ A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay 54585 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 58454♫ A Song For You Buble, Michael 47208 2012 Manja, Nikki & Sean, Jay 49117 A Song For You Charles, Ray 55249 21 -

Fulltext I Diva

Welcome Europe En undersökning av klipptekniker och kameraarbete i liveproduktioner med Eurovision Song Contest som utgångspunkt Författare: Malin Jakobsson Handledare: Per Erik Eriksson Examinator: Cecilia Strandroth Högskolan Dalarna Ämne: Bildproduktion 791 88 Falun Kurskod: BQ2042 Sweden Poäng: 15hp Examinationsdatum: 2017-12-05 Tel 023-77 80 00 Vid Högskolan Dalarna finns möjlighet att publicera uppsatsen i fulltext i DiVA. Publiceringen sker open access, vilket innebär att arbetet blir fritt tillgängligt att läsa och ladda ned på nätet. Därmed ökar spridningen och synligheten av uppsatsen. Open access är på väg att bli norm för att sprida vetenskaplig information på nätet. Högskolan Dalarna rekommenderar såväl forskare som studenter att publicera sina arbeten open access. Jag/vi medger publicering i fulltext (fritt tillgänglig på nätet, open access): Ja ☒ Nej ☐ Abstrakt Denna uppsats har som syfte att undersöka samt analysera klipptekniker och kameraarbete genom en jämförelse mellan Eurovision Song Contest år 2000 respektive år 2016. Detta för att visa på hur kamera och klippning påverkar bidrags konstnärliga uttryck samt diskutera en eventuell utveckling. Barry Salts arbete angående kopplingen mellan datainsamling och filmstil appliceras på denna uppsats och ger den dess metodologi. En djupgående analys på utvalda bidrag genomförs utifrån en multimodal infallsvinkel. Detta för att förtydliga förhållandet mellan diskurs och produktion och därigenom ge uppsatsen en beskrivning av klipptekniker och kameraarbetes vikt i bidragens individualitet. Uppsatsens undersökning samt analys visar på en förändring under åren. Speciellt i vilka tekniker som används för att uttrycka bidragens konstnärliga faktorer men det som kvarstår är viljan att anpassa det visuella arbetet efter varje bidrags specifika egenskaper. Nyckelord: Bildproduktion, liveproduktion, Eurovision Song Contest, utveckling, datainsamling, jämförelse.