Burning Down the House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

An Uncurling Hand Isolation in Public Places

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 An Uncurling Hand Isolation In Public Places Kimberly Kelley Lundblom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lundblom, Kimberly Kelley, "An Uncurling Hand Isolation In Public Places" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1761. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1761 AN UNCURLING HAND: ISOLATION IN PUBLIC PLACES by KIMBERLY KELLEY LUNDBLOM B.A. University of North Florida, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2011 Major Professor: Terry Thaxton © 2011 Kimberly K. Lundblom ii ABSTRACT The creative thesis ―An Uncurling Hand: Isolation in Public Places‖ is a collection of poetry concerned with ideological dichotomies: conventional domestication against the exotic, class divides and its implications for identity, and most importantly the feeling of isolation even when surrounded by others. iii I am grateful to Terry Thaxton, whose belief in my abilities was unwavering and life altering. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Writing Life Essay ............................................................................................................ -

Note: the Following List Is Only a Sampling of the Songs That Best Describe the Joker’S Wild

Note: The following list is only a sampling of the songs that best describe The Joker’s Wild. This is not an all-inclusive listing. The Joker’s Wild welcomes requests and music from a variety of genres. Ain't That A Kick In The Head Jump, Jive, an' Wail All of Me Just a Gigolo/I Ain't Got Nobody All The Way Just One of Those Things Angel Eyes Kansas City Angelina/Zooma-Zooma Kiss To Build a Dream On, A Are You Havin' Any Fun Lady is a Tramp, The As Long As I'm Singin' Let's Call The Whole Thing Off As Time Goes By Let's Fall in Love At Last Like Young Auld Lang Syne L-O-V-E Baby Please Come Home Love is the Tender Trap Banana Split For My Baby Luck Be a Lady Basin Street Blues Mack the Knife Besame Mucho Memories Are Made of This Best Is Yet To Come Moon River Beyond the Sea Moonlight in Vermont Bim Bam Moonlight Serenade Bla Bla Cha Cha Cha More Blue Alert Mustang Sally Buona Sera My Funny Valentine Can't Take That Away From Me New York, New York Cheek to Cheek Night and Day Come Fly With Me A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square Come Rain or Come Shine O Sole Mio Comin' Home Baby Oh Marie Crazy Lady Old Devil Moon Dig That Crazy Chick One For My Baby Do Nothin' Till Hear From Me Papa Loves Mambo Don't Get Around Much Anymore Paper Moon Down The Road I Go Pennies From Heaven Duke's Place Please Be Kind East of the Sun, West of the Moon Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone Easy To Love Pop-A-Diddy Fifteen on Fifteen Shadow of Your Smile, The Fine Romance, A Shape in a Drape Five Guys Named Moe Sing, Sing, Sing Five Months, Two Weeks, -

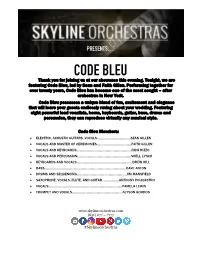

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Balch Family Papers

Collection 3058 Balch Family Papers Papers, 1755-1963 (bulk 1870-1920) 7 boxes, 44 volumes, 3 flat files, 6.9 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Processed by: Larissa Repin, Laura Ruttum & Joanne Danifo Processing Completed: September 2005 Sponsor: Phoebe W. Haas Charitable Trust Restrictions: None. Related Collections at See page 26 of the finding aid HSP: © 2005 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. Balch Family papers Collection 3058 Balch Family Papers, 1755-1963 (bulk 1870-1920) 7 boxes, 44 volumes, 3 flat files, 6.9 lin. feet Collection 3058 Abstract Thomas Balch (1821-1877) was born in Leesburg, Virginia to Lewis Penn Witherspoon Balch and Elizabeth Willis Weaver. He attended Columbia University and moved to Philadelphia, where he was admitted to the bar in 1850. In 1852, he married Emily Swift (1835-1917) and together they had three children: Elise Willing Balch (1853-1913), Edwin Swift Balch (1856-1927), and Thomas Willing Balch (1866-1927). The Balch family resided in Europe from 1859 to 1873 during which time Thomas (d. 1877) conducted research for several of the books and articles he wrote. His two most notable works are Les Francais en Amérique Pendant le Guerre de l’Indépendence, which explores France’s role in the American Revolution, and International Courts of Arbitration, which was written in aftermath of the sinking of the Alabama during the Civil War. Thomas Balch passed away in 1887 in Philadelphia. His sons Edwin Swift (d. -

Tea Trade, Consumption, and the Republican Paradox in Prerevolutionary Philadelphia Jane T

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Faculty Publications History 2004 Tea Trade, Consumption, and the Republican Paradox in Prerevolutionary Philadelphia Jane T. Merritt Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Merritt, Jane T., "Tea Trade, Consumption, and the Republican Paradox in Prerevolutionary Philadelphia" (2004). History Faculty Publications. 29. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs/29 Original Publication Citation Merritt, J. T. (2004). Tea trade, consumption, and the republican paradox in prerevolutionary Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography, 128(2), 117-148. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~£f ft"\ THE ~ Pennsylvania ~ OF HMO~YgA~~!r~\~APHY ~~~~~H=:;;;;;;~~~H~H~H~~~ Tea Trade, Consumption, and the Republican Paradox in Prerevolutionary Philadelphia N JANUARY 2, 1774, a usually cool and controlled William Smith 0 wrote heatedly to his trade partners in New York, "Vanderbelt has sent a parcell of his Trash to Town [per] White & Son wh [which] they confess is not good and are hurting us all by offering to fall the price. Mercer & Ramsay & myself have 4 Hhds [Hogsheads] I suppose of the same which am just told are come down ... from New York." He continued indignantly, "IfVanderbelt has Realy been guilty of Mixing his Tea & cannot be made to pay all damages for his Robbing the public & breaking all Mercantile faith, I think we have very little security for the Honor which is always suppos'd to subsist amongst Merchants had the thing happened here & been proved the Offender wd be consider'd in a most dispicable light."1 Smith's indignity over a merchant's lost honor had precedence. -

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 11/28/2020 7PM through 11/28/2020 11P s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 07:00:00p 00:00 Saturday, November 28, 2020 7PM 07:00:00p 04:27 INTO THE GROOVE / MADONNA 07:04:27p 04:11 YOU SHOULD BE DANCING / BEE GEES 07:08:38p 03:49 I'M COMING OUT / DIANA ROSS 07:12:27p 03:32 BIG SHOT / BILLY JOEL 07:15:59p 03:00 YOU MIGHT THINK / CARS 07:18:59p 03:32 BOOGIE NIGHTS / HEATWAVE 07:22:31p 03:40 THE HEAT IS ON / GLENN FREY 07:26:11p 03:10 HANDCLAP / FITZ & THE TANTRUMS 07:29:26p 03:30 STOP-SET 07:36:10p 03:49 JUMP / VAN HALEN 07:39:59p 03:42 I'M EVERY WOMAN (EDIT) / WHITNEY HOUSTON 07:43:41p 05:02 LOWDOWN / BOZ SCAGGS 07:48:43p 03:57 I'M YOUR BOOGIE MAN / K.C. & THE SUNSHINE BAND 07:52:40p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:00:00p 00:00 Saturday, November 28, 2020 8PM 08:00:00p 04:13 LOVE SHACK / B-52'S 08:04:13p 02:40 TAKE THE MONEY & RUN / STEVE MILLER BAND 08:06:53p 03:30 PUMP UP THE JAM / TECHNOTRONIC 08:10:23p 03:56 DRIVER'S SEAT / SNIFF 'N' THE TEARS 08:14:19p 03:39 WORKING FOR THE WEEKEND / LOVERBOY 08:17:58p 03:52 MAC ARTHUR PARK / DONNA SUMMER 08:21:50p 02:57 WAKE ME UP BEFORE YOU GO-GO / WHAM! 08:24:47p 04:27 BORN IN THE U.S.A. -

'Robert Sllis, Philadelphia <3Xcerchant and Slave Trader

'Robert Sllis, Philadelphia <3XCerchant and Slave Trader ENNSYLVANIA, in common with other Middle Atlantic and New England colonies, is seldom considered as a trading center for PNegro slaves. Its slave traffic appears small and unimportant when compared, for example, with the Negro trade in such southern plantation colonies as Virginia and South Carolina. During 1762, the peak year of the Pennsylvania trade, only five to six hundred slaves were imported and sold.1 By comparison, as early as 1705, Virginia imported more than 1,600 Negroes, and in 1738, 2,654 Negroes came into South Carolina through the port of Charleston alone.2 Nevertheless, to many Philadelphia merchants the slave trade was worthy of more than passing attention. At least one hundred and forty-one persons, mostly Philadelphia merchants but also some ship captains from other ports, are known to have imported and sold Negroes in the Pennsylvania area between 1682 and 1766. Men of position and social prominence, these slave traders included Phila- delphia mayors, assemblymen, and members of the supreme court of the province. There were few more important figures in Pennsyl- vania politics in the eighteenth century than William Allen, member of the trading firm of Allen and Turner, which was responsible for the sale of many slaves in the colony. Similarly, few Philadelphia families were more active socially than the well-known McCall family, founded by George McCall of Scotland, the first of a line of slave traders.3 Robert Ellis, a Philadelphia merchant, was among the most active of the local slave merchants. He had become acquainted with the 1 Darold D. -

The Descendants of Jöran Kyn of New Sweden

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 0807 625 5 ' i 1 . .a i ',' ' 't "f i j j 1" 1 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation V http://www.archive.org/details/descendantsofjOOkeen J 'A €. /:,. o Vt »,tT! ?"- ^^ ''yv- U'l 7- IL R Xj A The Descendants of JORAN KYN of New Sweden By GREGORY B. KEEN, LL.D. Vice President of the Swedish Colonial Society Philadelphia The Swedish Colonial Society 1913 .^^,^^ mu^ printed bv Patterson & White Company 140 North Sixth Street philadelphia. pa. In Memoriatn Patris, Matris et Conjugis Stirpts Pariter Scandinaviensis Foreword This work comprises (with mimerous additions) a series of articles originally printed in The Pennsylvania Maga- zine of History and Biography, volumes II-VII, issued by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania during the years 1878-1883. For the first six generations included in it, it is, genealogically, as complete as the author, with his pres- ent knowledge, can make it. Members of later generations are mentioned in footnotes in such numbers, it is believed, as will enable others to trace their lineage from the first progenitor with little difficulty. It is published not merely as the record of a particular family but also as a striking example of the wide diffusion of the blood of an early Swedish settler on the Delaware through descendants of other surnames and other races residing both in the United States and Europe. No attempt has been made to intro- duce into the text information to be gathered from the recent publication of the Swedish Colonial Society, the most scholarly and comprehensive history of the Swedish settle- ments on the Delaware written by Dr. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

The Future of Youth Justice: a Community-Based Alternative to the Youth Prison Model Patrick Mccarthy, Vincent Schiraldi, and Miriam Shark

New Thinking in Community Corrections OCTOBER 2016 • NO. 2 VE RI TAS HARVARD Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management The Future of Youth Justice: A Community-Based Alternative to the Youth Prison Model Patrick McCarthy, Vincent Schiraldi, and Miriam Shark Introduction Executive Session on [F]airly viewed, pretrial detention of a juvenile Community Corrections gives rise to injuries comparable to those associated This is one in a series of papers that will be with the imprisonment of an adult. published as a result of the Executive Session on —Justice Thurgood Marshall Community Corrections. It is, in all but name, a penitentiary. The Executive Sessions at Harvard Kennedy School bring together individuals of independent —Justice Hugo L. Black standing who take joint responsibility for rethinking and improving society’s responses to an issue. Members are selected based on their Is America getting what it wants and needs by experiences, their reputation for thoughtfulness, incarcerating in youth prisons young people who and their potential for helping to disseminate the get in trouble with the law? work of the Session. Members of the Executive Session on Community If not, is there a better way? Corrections have come together with the aim of developing a new paradigm for correctional policy For 170 years, since our first youth correctional at a historic time for criminal justice reform. The Executive Session works to explore the role of institution opened, America’s approach to youth community corrections and communities in the incarceration has been built on the premise that a interest of justice and public safety. -

MOVE Bombing Or What Is Called “May 13, 1985” in West Philadelphia, Was a Pivotal Moment in the Mayoral Reign of Wilson Goode and Was the First Time a U.S

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 MOVE: Philadelphia's Forgotten Bombing Charles Abraham Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the United States History Commons Abraham, Charles, "MOVE: Philadelphia's Forgotten Bombing" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/move/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVE: Philadelphia’s Forgotten Bombing Charles Abraham James Madison University In a fortified rowhouse in West Philadelphia, a bomb dropped by Philadelphia Police killed eleven MOVE members, including five children, and burned down sixty-five other houses after a lengthy standoff between the two groups. MOVE was a cult-like organization which eschewed technology, medicine and western clothing, where members lived communally, ate raw food, left garbage on their yards, and proselytized with a loudspeaker, frustrating the residents of Osage Avenue. The MOVE Bombing or what is called “May 13, 1985” in West Philadelphia, was a pivotal moment in the mayoral reign of Wilson Goode and was the first time a U.S. city bombed itself. The bomb dropped on the MOVE rowhouse with only marginal consequences to the city government because of previous encounters with MOVE and antipathy in the public towards the MOVE organization resulting in the group falling into obscurity.1 1 For further reading on cults in America, see Willa Appel, Cults in America: Programmed for Paradise (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1983) which discusses the phenomenon of cults and how one is indoctrinated or breaks out of a cult.