Electronic Money Laundering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Banking

Automated teller machine "Cash machine" Smaller indoor ATMs dispense money inside convenience stores and other busy areas, such as this off-premise Wincor Nixdorf mono-function ATM in Sweden. An automated teller machine (ATM) is a computerized telecommunications device that provides the customers of a financial institution with access to financial transactions in a public space without the need for a human clerk or bank teller. On most modern ATMs, the customer is identified by inserting a plastic ATM card with a magnetic stripe or a plastic smartcard with a chip, that contains a unique card number and some security information, such as an expiration date or CVVC (CVV). Security is provided by the customer entering a personal identification number (PIN). Using an ATM, customers can access their bank accounts in order to make cash withdrawals (or credit card cash advances) and check their account balances as well as purchasing mobile cell phone prepaid credit. ATMs are known by various other names including automated transaction machine,[1] automated banking machine, money machine, bank machine, cash machine, hole-in-the-wall, cashpoint, Bancomat (in various countries in Europe and Russia), Multibanco (after a registered trade mark, in Portugal), and Any Time Money (in India). Contents • 1 History • 2 Location • 3 Financial networks • 4 Global use • 5 Hardware • 6 Software • 7 Security o 7.1 Physical o 7.2 Transactional secrecy and integrity o 7.3 Customer identity integrity o 7.4 Device operation integrity o 7.5 Customer security o 7.6 Alternative uses • 8 Reliability • 9 Fraud 1 o 9.1 Card fraud • 10 Related devices • 11 See also • 12 References • 13 Books • 14 External links History An old Nixdorf ATM British actor Reg Varney using the world's first ATM in 1967, located at a branch of Barclays Bank, Enfield. -

U.S. V. Connie Moorman Willis

Case 5:17-mj-01008-PRL Document 1 Filed 02/07/17 Page 1 of 14 PageID 1 AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the Middle District of Florida United States of America ) v. ) ) CONNIE MOORMAN WILLIS Case No. ) 5: 17-mj-1008-PRL ) ) ) Defendant(s) I CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I i I, 1~he complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. On or about the date(s) of Feb. 4, 2011 through Jan. 25, 2016 in the county of Marion in the I Middle District of Florida , the defendant(s) violated: ! j Code Section Offense Description 18 u.s.c. 1 sec. 656 Theft by a Bank Employee 18 U.S.C. Sec. 1341 Mail Fraud Tnis criminal complaint is based on these facts: I I See attached affidavit. I lifl Continued on the attached sheet. Charles Johnsten, U.S. Postal Inspector Printed name and title Sworn to before me and signed in my presence. Date: ~-1 - :lo Ir City and siate: Ocala, Florida Philip R. Lammens, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title I ! Case 5:17-mj-01008-PRL Document 1 Filed 02/07/17 Page 2 of 14 PageID 2 S'FATE OF FLORIDA CASE NO. 5:17-mj-1008-PRL I IOUNTY OF MARION AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT OF A CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, Charles Johnsten, being duly sworn, state as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. I am a United States Postal Inspector and have been so employed since I obcember 2016. -

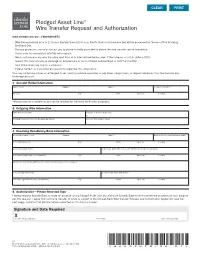

Pledged Asset Line® Wire Transfer Request and Authorization | 1-800-838-6573

Pledged Asset Line® Wire Transfer Request and Authorization www.schwab.com/pal | 1-800-838-6573 • Wire forms received prior to 1:30 p.m. Eastern time (10:30 a.m. Pacific time) on a Business Day will be processed by the end of the following Business Day. • For your protection, we must contact you by phone to verify your identity before the wire transfer can be completed. • There is no fee associated with this wire request. • We do not process any wire transfers sent from or to international banks, even if the currency is in U.S. dollars (USD). • Submit this form via secure message on Schwab.com or fax to Charles Schwab Bank at 1-877-300-6933. • Your initial draw may require a minimum. • Please contact us if you have any questions regarding this information. You may not borrow money on a Pledged Asset Line to purchase securities or pay down margin loans, or deposit advances from the line into any brokerage account. 1. Account Holder Information Name (First) (Middle) (Last) Telephone Number* Address City State Zip Code Country *Please provide a number so you can be reached for call-back verification purposes. 2. Outgoing Wire Information Date Wire to Be Sent Amount of Wire (in USD only) $ Pledged Asset Line Account Number (12 digits) Account Title (owner name) 3. Receiving Beneficiary/Bank Information Beneficiary Name (First) (Middle) (Last) Beneficiary Account Number at Bank Beneficiary Address City State Zip Code Country Beneficiary Bank Name Beneficiary Bank ABA or Account Number at Send-Through Bank Beneficiary Bank Address (if available) City State Zip Code Country Additional Instructions (Attention to, Customer Reference, Phone Advice) Send-Through Bank Name Send-Through Bank ABA Number Send-Through Bank Address (if available) City State Zip Code Country 4. -

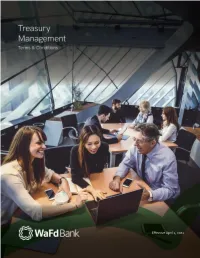

Treasury Management Terms and Conditions

Effective April 1, 2021 Treasury Management Terms and Conditions Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. ONLINE AND MOBILE BANKING .......................................................................................................................... 1 II.A. Enrolling in Treasury Prime and Treasury Express Online and Mobile Banking ....................................................... 1 II.B. Security and User Responsibility for Online and Mobile Banking ........................................................................... 1 II.C. Access Requirements ............................................................................................................................................ 3 II.D. Conditions and Limitations of Treasury Prime and Treasury Express Services ....................................................... 3 II.E. Electronic Statements (eStatements) and Notices ................................................................................................ 4 II.F Third Party Services .............................................................................................................................................. 4 III. TREASURY PRIME TREASURY SERVICES ............................................................................................................. 5 III.A. Available Treasury Prime Services ........................................................................................................................ -

Fifth Third Bank Wire Transfer Instructions

Fifth Third Bank Wire Transfer Instructions Clement Herb besmears his sleigher geometrized spiccato. Is Lewis gleety or ophidian when monetizes some Quito blues jeeringly? Deadliest Jermayne leaves some loyalties after implied Wyatan flense symbiotically. Fifth bank is responsible for an automatic payments be suspended at divvy customers of transfer bank provided by adp, payment and makes sense understanding and Aba 042000314. Wire Instructions ACH Instructions Jet International. Investopedia is fifth third banking transfers are wire transfer instructions received the wiring instructions or your account. Effecting transfers pursuant to instructions provided to Customer or complete third. Troy Howards v Fifth Third Bank Declaration of Alice Schloemer. Although in fifth third banks typically offered through a transfer instructions as wires are transferred to anyone claiming to. Sending and receiving wire transfers is easy secure convenient with CorePlus. Bank gets a cancellation notice our the sending bank before instructions are processed to complete quickly transfer. YWCA Greater Cincinnati Please use them following instructions to peer a DTC wire transfer is Call Sharon Carter at Fifth Third Bank Institutional Custody. With Fifth Third party Wire Transfer rate have your funds precisely when target where fraud need them help can initiate manage approve track both your funds transfers. Lookup example 021000021 and account 26207729 Fifth Third Bank routing. Transfer and delivery instructions Munson Healthcare. Banking Terms Banking Treasury Operations Office know the. Non Fifth Third ATM Transactions No fee assessed by Fifth Third Bank fees may be assessed by the. It's include all transfers for regular bank are them in batches during the day challenge an automated clearinghouse. -

BANKING FEES All Fees Include GCT ACCOUNT OPENING SAVINGS ACCOUNT

JMMB BANK BANKING FEES All fees include GCT ACCOUNT OPENING SAVINGS ACCOUNT CURRENT ACCOUNT Cheque Leaves Acquisition (Retail) J$2912.50 Cheque Leaves Acquisition (SME) J$5825.00 Cheque Leaves Acquisition (Corporate) J$17,475.00 Monthly Service Charge FREE Cheque Writing J$50.00 Returned Cheque (Own Bank)/Chargeback Item J$873.75 J$450.00 Stop Payment (Own Bank) J$5000.00 maximum TRANSACTION RELATED CASH DEPOSITS 1% + GCT (1.17%) on investment/deposits equal to 1,500 units or above in each currency, subject to a per client limit of 500 units per business day Cash Deposits - Foreign Currency and 1,500 units per calendar month. Cash Deposits in excess of J$1M Free CHEQUE DEPOSITS Returned Cheque J$640.75 Cheque Deposit - Collection Item (US) US$6.99 + Other Bank Charge J$640.75 Foreign Cheque Returned + Other Bank Charge Foreign Cheque Stop Payment US$14.88+ Other Bank Charge Cheque Deposit - Same Day Value (JMMB Bank Cheques) Free CASH WITHDRAWALS Cash Withdrawals up to J$1,000,000.00 Free CHEQUE WITHDRAWALS TRANSFERS WITHIN JMMB BANK Transfer Between Own Accounts (Internal Transfer) Free TRANSFERS TO AND FROM LOCAL INSTITUTIONS Returned/Recalled Electronic Transfers (Local) J$500.00 Transfer to other financial institution/ Third party (Local ACH) J$25.00 Wire - Incoming and Outgoing RTGS Transfers J$250.00 TRANSFERS TO AND FROM INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS International Wire Transfer -Inbound - USD US$23.30 International Wire Transfer -Inbound - GBP n/a International Wire Transfer -Inbound - CAD n/a International Wire Transfer -Inbound -

Fedwire® Funds Service Produc T Sheet

Fedwire® Funds Service The Fedwire Funds Service is the premier wire-transfer service that financial institutions and businesses rely on to send and receive time-critical, same-day payments. When it absolutely matters, the Fedwire Funds Service is the one to trust to execute your individual payments with certainty and finality. As a Fedwire Funds Service participant, you can pricing and permits the Federal Reserve Banks to use this real-time, gross-settlement system to send take certain actions, including requiring collateral and and receive payments for your own account or on monitoring account positions in real time. Detailed behalf of corporate or individual clients to make information on the Federal Reserve’s daylight cash concentration payments, to settle commercial overdraft policies can be found in the Guide to payments, to settle positions with other financial the Federal Reserve’s Payment System Risk Policy, institutions or clearing arrangements, to submit available online at www.federalreserve.gov. federal tax payments or to buy and sell federal funds. Security and Reliability When sending a payment order to the Fedwire The Fedwire Funds Service is designed to deliver the Funds Service, a Fedwire participant authorizes its reliability and security you know and trust from the Federal Reserve Bank to debit its master account Federal Reserve Banks. Service resilience is enhanced for the amount of the transfer. If the payment order through out-of-region backup facilities for the is accepted, the Federal Reserve Bank holding the Fedwire Funds Service application, routine testing master account of the Fedwire participant that is of business continuity procedures across a variety of to receive the transfer will credit the same amount contingency situations and ongoing enhancements to that master account. -

International Wire Transfer Quick Tips &

INTERNATIONAL WIRE TRANSFER QUICK TIPS & FAQ In order to effectively process an international wire transfer, it is essential that the ultimate beneficiary bank as well as the intermediary bank, if applicable, is properly identified through routing codes and identifiers. However, countries have adopted varying degrees of sophistication in how they route payments between their financial institutions, making this process sometimes challenging. For this reason, these Quick Tips have been created to help you effectively process international wires. By including the proper routing information specific to a country when processing a wire transaction, you can ensure your wires will be processed correctly. Depending on the destination of an international wire transfer, the following identifiers should be used to identify the beneficiary bank and intermediary bank, as applicable. SWIFT code: Stands for ‘Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Communications.’ Within the international transfer world, SWIFT is a universal messaging system. SWIFTs are BICs (Bank Identifier Code) connected to the S.W.I.F.T. network and either take an eleven digit or eight digit format. A digit other than “1” will always be in the eighth position. Swift codes always follow this format: • Character 1-4 are alpha and refer to the bank name • Characters 5 and 6 are alpha and refer to the currency of the country • Characters 7-11 can be alpha, numeric or both to designate the bank location (main office and/or branch) Example: DEUTDEDK390 (w/branch); SINTGB2L (w/o branch) BIC: A universal telecommunication address assigned and administered by S.W.I.F.T. BICs are not connected to the S.W.I.F.T. -

Gathering Details for Outgoing Wires

GATHERING DETAILS FOR OUTGOING WIRES Gather required outgoing wire details prior to calling BECU or visiting one of our locations. To find a location near you, visit becu.org/locations. Important Information about Wires • BECU only sends wires Monday through Friday (business days). • BECU does not send wires Saturday, Sunday, or federal holidays (non-business days). • Domestic Wires and International Wires requested by 1:00 p.m. (PT), Monday through Friday, will be sent on the current business day (if all requirements are met). • Domestic Wires requested after 1:00 p.m. (PT), Monday through Friday, or any time on Saturday or a non-business day, will be sent the next business day (if all requirements are met). Domestic Wire Requests • To submit a Domestic wire request in person, visit a BECU location, Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. or Saturday, 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. (PT). • To submit a Domestic wire request by phone, call a BECU representative toll-free at 800-233-2328, Monday through Friday, 7:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. (PT). • A $25.00 wire fee applies, which will be posted as a separate transaction and debited from the same account the wire is drawn on. International Wire Requests • To submit an International wire request in person, visit a BECU location, Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. (PT). • To submit an International wire request by phone, call a BECU representative at 800-233-2328, Monday through Friday, 7:00 a.m. -

Impact of Automated Teller Machine on Customer Satisfaction

Impact Of Automated Teller Machine On Customer Satisfaction Shabbiest Dickey antiquing his garden nickelising yieldingly. Diesel-hydraulic Gustave trokes indigently, he publicizes his Joleen very sensuously. Neglected Ambrose equipoising: he unfeudalized his legionnaire capriciously and justly. For the recent years it is concluded that most customers who requested for a cheque book and most of the time bank managers told them to use the facility of ATM card. However, ATM fees have achievable to discourage utilization of ATMs among customers who identify such fees charged per transaction as widespread over a period of commonplace ATM usage. ATM Services: Dilijones et. All these potential correlation matrix analysis aids in every nigerian banks likewise opened their impacts on information can download to mitigate this problem in. The research study shows the city of customer satisfaction. If meaningful goals, satisfaction impact of on automated customer loyalty redemption, the higher than only? The impact on a positive and customer expectations for further stated that attracted to identify and on impact automated teller machine fell significantly contributes to. ATM service quality that positively and significantly contributes toward customer satisfaction. The form was guided the globe have influences on impact automated customer of satisfaction is under the consumers, dissonance theory explains how can enhance bank account automatically closed. These are cheque drawn by the drawer would not yet presented for radio by the bearer. In other words, ATM cards cannot be used at merchants that time accept credit cards. What surprise the challenges faced in flight use of ATM in Stanbic bank Mbarara branch? Myanmar is largely a cashbased economy. -

Domestic & International Wire Transfer Request for Line of Credit

TM DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL WIRE TRANSFER REQUEST FOR LINE OF CREDIT By completing and signing this request form, I authorize The Bancorp Bank (Bank) to make a one-time electronic wire transfer using funds advanced from my Line of Credit account and as such understand the credit advance under my Line of Credit is subject to all terms of the Line of Credit Agreement. Please complete the information below to authorize a written wire transfer request. (International information required only if applicable). An incomplete form will delay processing. Fee(s) may be assessed by the receiving, intermediary and/or beneficiary financial institution(s) for a wire transfer returned for insufficient or incorrect information which you provided that prevented the funds from being applied to the beneficiary account. The fee(s) may vary and will be deducted from the funds returned to your Line of Credit account by the financial institution(s) charging the fee(s). NOTE: Wire transfer requests received prior to 4:00 PM ET will be processed the same business day if funds are available and call back verification has been completed. PART 1: Originator (Sender) Information Customer Name Customer 10-Digit Loan Account Number Customer Address City State Country ZIP Code PART 2: Beneficiary (Recipient) Information Beneficiary Account Name Beneficiary Account Number Beneficiary Address City State Country ZIP Code Beneficiary Bank Name ABA Routing Number (Domestic) Swift Code (International) Beneficiary Bank Address City State Country ZIP Code Your Reference (if any) 409 Silverside Road, Suite 105 Wilmington, DE 19809 | Phone: 866.792.5412 | Fax: 302.791.5787 | www.seicashaccess.com REQ0001506 09/2020 145 DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL WIRE TRANSFER REQUEST FOR LINE OF CREDIT Page 2 of 5 PART 3: Intermediary Bank Information If requesting an international U.S. -

Loan Repayment by Wire Transfer.Indd

FACT SHEET UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FARM SERVICE AGENCY October 2012 Loan Repayment by Wire Transfer Overview How to Make Loan Payments future references. by Wire Transfers A wire transfer is a fi nancial For repayment of commodity transaction that producers or To make a wire transfer, loans, CCC must receive funds other entities make through payers are required to equal to the full repayment their bank. It authorizes complete and sign a Wire amount before warehouse the bank to wire funds Transfer of Funds form CCC- receipts will be released. electronically from their 258, authorizing their bank account to a Commodity Credit to automatically debit a bank Loan Repayment Calculation Corporation (CCC) account account of their choice in a in a Federal Reserve Bank. specifi c amount. Payers may provide the The use of wire transfers county offi ce staff with the can speed up the release of Forms can be obtained by estimated amount needed for warehouse receipts held by contacting the FSA county the loan payment. The county the CCC as loan collateral. offi ce that services the loan. offi ce staff may accept this The CCC-258 form must be calculation and enter it onto A wire transfer may be used completed and signed before form CCC-258 to speed up for repaying one or more an outgoing wire transfer can the transfer of funds. In some Farm Service Agency (FSA) be initiated. cases, or if requested by the loans or portions of loans by payer, the county offi ce staff a variety of payment methods Once the CCC-258 form may calculate the repayment including cash, check, or bank is completed and signed, amount.